|

Everything Might Break Is it might that smashes down upon the dinner table? Is that what you would call my husband’s fist, shattering our evening meal? The chicken is dry, tough as leather, he says. His jaw’s strength is not enough to rend it, he says. The peas are on the floor now, tender, hand-hulled, soft and buttered - just the way he loves them best. Not that he can taste them, pinched as they are in the treads of his boot. The chair is on its side, the first casualty of our little war, a steadfast officer down while its brethren watch, unmoved. Might be broken, might just need a little glue. Wouldn’t be the first time, might be the last. One of these nights has to be the last, doesn’t it? We can’t go on like this forever. It was just a thrift store find anyway, chipped-up hard-wood, old but sturdy. It was knocked back when he stood, knocked out when his fist fell. The sauce is spilling across the tablecloth, seeping into worn threads, torn seams. It’s a tattered old rag, but I love it. One of the few things that was mine before I came here, met him. It could take hours to soak it, scrub it out. I’ll have to scald my hands, since butter never comes out without a bit of heat. Could be worse. Could be blood. Easier to clean, but I could stain it faster than I wash it. Wood creaks under his hands. I might have spoken too soon. The chicken was very tough, after all. Blood is not yet off the table. The blinds are always pulled closed. He works at night, sleeps in the day, so it has to be dark, he says. No one sees in, no one sees out, I say. Sometimes I imagine someone there, just outside.They might see me and open everything up. A fantasy, a little game I play. I don’t have neighbors, and if I did I wouldn’t know their names. The bowl teeters, trembling on the edge. It was a gift, for our wedding, from a friend whose face I can no longer remember. Blown glass, one of a kind. It is beautiful, but not practical. It lingers, just about to fall. I watch it, until the buttons of his shirt take its place before my eyes. I might fall first, but I won’t shatter. Nat Richards Nat Richards is a student of all forms of writing. Her works have appeared in TeenInk and in the three romantic anthologies Sunkissed: Effusions of Summer (Meryton Press, 2015), Then Comes Winter (Meryton Press, 2015), and The Darcy Monologues (Quill Ink, 2017). She currently lives in Oregon and cannot imagine living anywhere without a nearby forest.

0 Comments

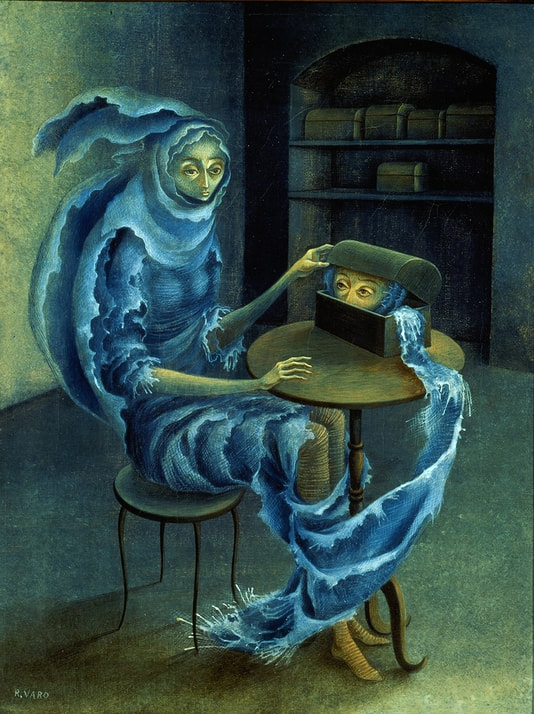

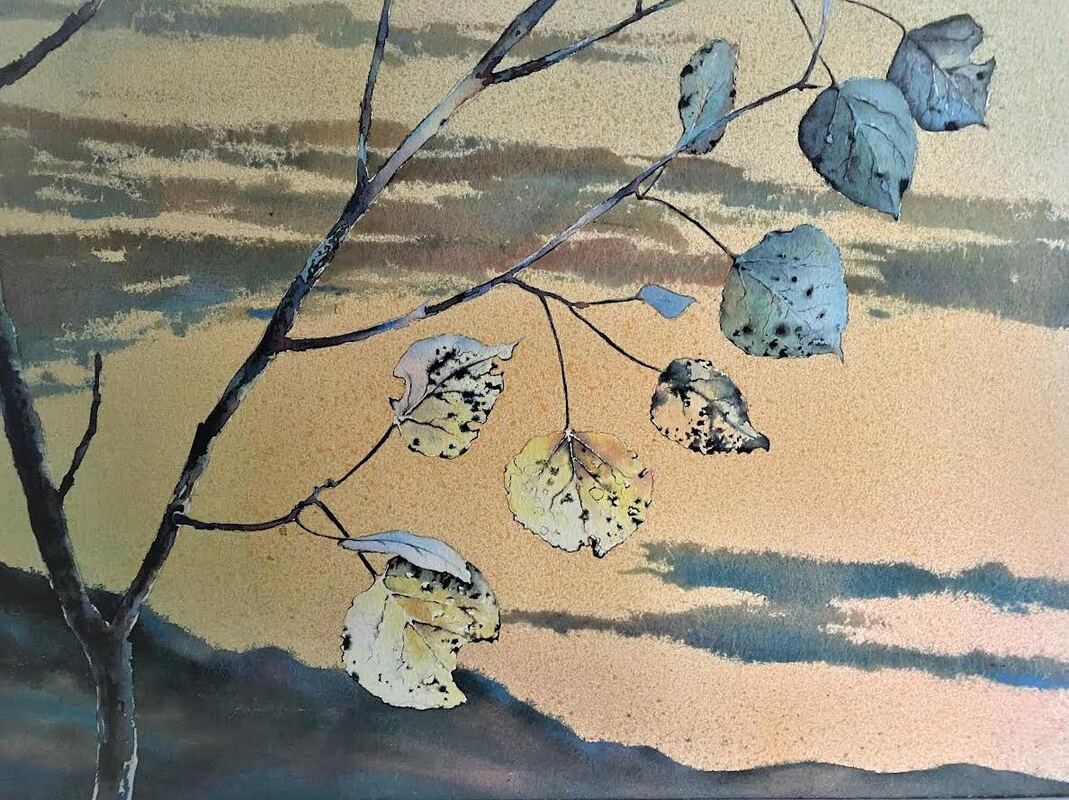

If I Were Water I’d turn myself into cumulus cloud fluffy and white that the whole world would want to jump on me like a feather bed. If I were water, I’d become a hailstone and crash down onto an asphalt parking lot on a hot and sticky August day. I’d bounce off windshields and front walks and grow to the size of a baseball so a little boy would gather me in his hand to show his mother and then place me in the freezer next to the ice cubes and popsicles. If I were water, I’d turn into a puddle where Robins and Sparrows drink and bathe, fluttering their wings, drenching their tails. In the fall I’d become a thin layer of ice so I could feel the crack of the heel of a boot on a young girl breaking ice for the first time. When I tired of this, I’d transform into a one-of-a-kind snowflake. I’d be the most beautiful snowflake in the world, floating down, down, down onto a field where I’d land on the wooden post of a split rail fence, topping it like a layer of white icing on a cupcake. If I were water, I’d transform myself into a thick fog and blanket a sleeping village so the foghorn could blast Ooh, Ooh, Ooh and then I’d burn off and become a cirrus cloud and fly like a magic carpet all the way around the world. If I were water, I’d cry when I saw rivers filled with plastic bags and old cans and bottles. I’d beat down onto filthy streets to rid them of oil and grime. If I were a drop of water, I would sit in a dog’s bowl wating for its pink tongue to lap me up. If I were water, I’d put out forest fires, save the homes of squirrels and deer and all the birds. I’d feed the deep roots of Redwoods and Maples, and on mornings, slip as a drop of dew from their leaves and sparkle. If I were water, I’d refrain from cresting in a river, or breaching a dam or flooding a cellar. If were water, I’d gladly fill a bathtub, and brush your teeth and wash your hair in the shower, my soothing drops lulling you awake, rinsing you clean, steaming up your mirror. If I were water, I’d disappear for a day every so often and imagine you saying, What a wonderful day, not a cloud in the sky! Because I know you’d miss me. Water Nymph Water flows from my wrists and elbows like rivulets. It cascades down my back, pools at my feet. I shower anyone who approaches me in this grotto. I am fountain, geyser, watery chimera. My fingers, waterfalls. Circulating, flowing. Never turned into clouds, or fog, or snow. I am never to feel the coolness of fresh, dry sheets, or fallen leaves crunching underfoot, or the warmth of a smooth, round stone heated under a noon sun. I am forever liquid. Items fall through me, or float on my surface. A man appears, tall, tan and bronzed from the sun. A trickle of sweat on his brow. He places his pinky into my elbow like a boy at a water fountain, then tilts his head, leans over and takes a long drink. I feel nothing. I long to embrace the solid, the dry, to touch this man’s eyelashes, his golden hair, feel the heat of his chest, brush my lips against his. But I cannot. All I know is wet, rushing water. He steps back and studies my soggy presence, his eyes move to my face, my eyes, my mutable limbs as he makes out the undulating outline of me. He steps towards me, then pushes his brawny fingers through the surface of my chest and his entire hand goes right through me. He holds it there, mesmerized, as I rush and swirl around him. He withdraws his arm, stares at his dripping sleeve, then at me disbelieving. I grin, my face rippling, my expression full of waves. Andrew Marcusa Andrea Marcusa’s literary fiction, essays and poetry have appeared in The Gettysburg Review, Booth, Citron Review, New South, River Styx, River Teeth and others. She’s received recognition from the writing competitions Glimmer Train, New Letters, Raleigh Review and Southampton Review. Andrea divides her time between creating literary works and photographs and writing articles on medicine, technology, and education. To learn more visit: andreamarcusa.com or follow her on Twitter @d_marcusa Aspen Leaves Justin Locke’s watercolour, Aspen Leaves, is haunting even for those not acquainted with the high country. The scene is depressingly austere: dying leaves cling to dying branches on a dying day. And yet there is beauty here: the fading yellow of the sky, a gauze of gray clouds fingering across, a message of satisfaction that the day was acceptably free of disappointment. But the leaves are yellowed, pitted from insect diets, scabbed with uninvited mildews. They have long lost their summer tint, the deciduous lizard green among darker forest conifers. They are spent—as is the day itself. There is no promise here. Only the resolution to clone new offspring to poke through snowmelt when spring permits. Only the perseverance to prevail on an uncontested patch of high meadow. However, there are nested layers of reality behind the pigments and the brush strokes, and these entangle my mind. There’s first the art itself: the pastel play of colour, the subtle texture of the clouds, the gaunt asymmetry of the branches. The scene itself has a brittle sadness, a nocturne playing across it. My gut response is best described (if at all) through colors and sounds and tastes, not by words. This is a reality partly independent of the leaf, the tree, the landscape, but evoked thereby. It is this play on my senses alone that initially seizes my attention and causes me to procrastinate. Then there’s the layer behind the art, the reality that the artist witnessed and transformed for me to see. It lies in the memories of those of us who trek the wilderness: a broader reality that encompasses the entire tree and beyond. It embraces the collective assembly defining the single organism of the aspen stand. It incorporates, as well, the others peppering the distant mountainsides with yellow patches of autumn. This is the reality of accessible memory, which embellishes the aspen with those humanizing verbs—to resolve, to persevere—assigning agency. The deeper layer is the reality I encounter when standing there in the remote chill at high elevation, the aroma of spruce and fir enshrouding me, the wind whispering across treetops, all of my senses captive. Unembroidered, there are no judgments here, no moral residues. There is no resolution to clone; no perseverance to prevail. The tree does not struggle. It simply is. The sundry living forms, seen and not, are neither sublime nor purgatorial. They are simply pervasive and cyclical. A tiny fragment of this cycle is what the artist has captured. It is what calls up the conflicting layers of my world and invites me to linger. Ron Wetherington Ron Wetherington is a retired anthropologist living in Dallas, Texas. He has a published novel, flash non-fiction in The Dillydoun Review, and upcoming fiction in Words & Whispers and Flash Fiction Magazine. black after Lorette C. Luzajic's poem titled “white” from Winter in June. Click here to read it (scroll way down). for Frida, Clarice, Parveen & Lorette ... / black diamond apple / aeonium arboreum / pegasus / nefertiti / كسوة الكعبة* / حجرِاسود** / marquina black / japanese bobtail, scottish fold, bombay, oriental, sphynx, ragamuffin, chantilly-tiffany / labrador retriever, scottish terrier, newfoundland, affenpincher, schipperke, puli / peter green’s black magic woman: “... yes, i got a black magic woman ... and she’s trying to make a devil out of me ...” / jimi hendrix, bob marley, thin lizzy / truffle / wood ear / eggplant / kala namak*** / black pepper / kalonji / jaiur / douchi / caviar / othello grapes / jamun berries / black plum jam / rye bread / expresso / toblerone dark / strix huhula / cygnus atratus / “baa baa black sheep, have you any wool?” / dunbar’s “we wear the mask”: we wear the mask that grins and lies, it hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,-- this debt we pay to human guile; with torn and bleeding hearts we smile, and mouth with myriad subtleties. / m. luther king jr. / black country & britain’s coal mines / black lives matter / kalima hora / walker, basquiat, tanner, lewis--insurrection!, untitled, nicodemus visiting jesus, colonel robert gould shaw / m. ali, sir v. richards, u. bolt / poe’s the black cat: “who has not, a hundred times, found himself committing a vile or silly action for no reason than because he knows he should not? have we not a perpetual inclination, in the teeth of our best judgement, to violate that which is law, merely because we understand it to be such?” / panthera-pardus/onca / bos grunniens / dasyatis thetidis / dendroaspis polylepis / naja melanoleuca / latrodectus hesperus / pandinus imperator / black sea / orcinus orca / tahitian pearl / black friday / black forest / black magic / black mirror / black hole / lamy fountain pen ink / handmade bound notebook / samsung galaxy tablet / windows or apple or google theme / funeral dress / kali mata! shakti de!**** / ...

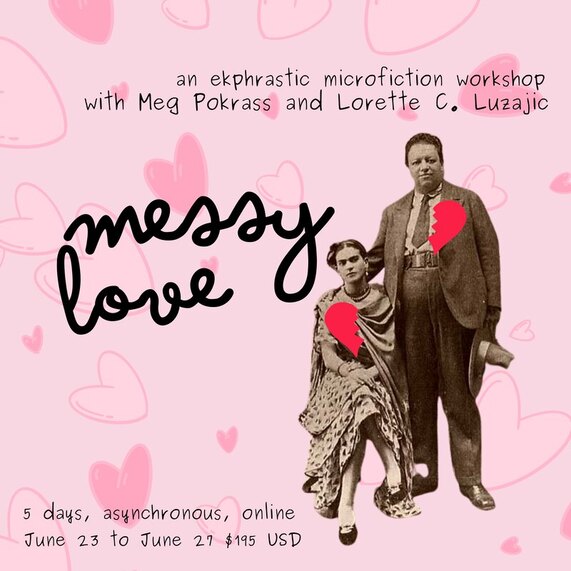

Saad Ali N.B.: 1. Kiswat al-ka'bah = Black cloth, which is used as a cover for the Ka’bah in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. Ka’bah (‘The Cube’), or the House of God, is the holy site for Muslims. 2. Hajaru al-Aswad = Black rock, which is installed in the eastern corner of the Ka’bah. According to the Islamic tradition, it date backs to the time of Hazrat Adam (Adam) and Bibi Hawa (Eve). 3. Himalayan black salt. 4. O Mother Kali! Give me strength!—where, kali = she who is black and shakti = strength. According to the Hindu tradition (mythology), Kali is the Goddess of Time and Death. Saad Ali (b. 1980 C.E. in Okara, Pakistan) has been brought up in the UK and Pakistan. He holds a BSc and an MSc in Management from the University of Leicester, UK. He is an (existential) philosopher, poet, and translator. Ali has authored six collections of poetry. His new collection of poems is titled Owl Of Pines: Sunyata (AuthorHouse, 2021). He is a regular contributor to The Ekphrastic Review. By profession, he is a Lecturer, Management Consultant, and Trainer/Mentor. Some of his influences include: Vyasa, Homer, Ovid, Attar, Rumi, Nietzsche, and Tagore. He is fond of the Persian, Chinese, and Greek cuisines. He likes learning different languages, travelling by train, and exploring cities on foot. To learn more about his work, please visit www.saadalipoetry.com, or his Facebook Author Page at www.facebook.com/owlofpines. We Visit Valencia to See the Red Ink Running Through Her Veins When we enter the cave, Maria says, “We’ve always been such simple people.” And it’s true, glancing over countless etchings of spears in antelope, we've always been the animals I fear the most. It’s the middle of December and icicles frame the outside of the cave. There are eight of us inside, not including the tour guide, Johnny, a local college student underpaid to trek to the northern hollows three times a day. Johnny steps on a slug at the entrance of the cave, and he identifies its corpse as an Arion Lasitanicus. Maria and I stop behind the rest of the group and wait for Johnny to resume his guidance. He scrapes the remains of translucent juice from his rubber sole. As we turn the corner, we are greeted by more walls of red and black ink on beige limestone. Johnny tells us, “These paintings were most likely done to commemorate the ending of a tribal war.” I see my girlfriend, Maria, on the outskirt of the group, captivated by the image of a small boy, but refusing to look at the images of the dead antelopes. Even now, she is still a child covering her eyes from roadkill. Her retinas are avoiding the violence, but I know she is still curious about everyone who lives and dies on this surface. Her eyes scan over the images of her ancestors: First, the antelope. Then, the hunter. Watching her look at these images, I know she is sifting through her lineage because she carries these sketches in her chest. On the hike up to the cave, Maria started teaching me some Spanish. “In English,” she said, “The verb, sift, literally means, to take out the unwanted leaving only the pure remnants,” she put her hand on the guardrail on the path and stopped to inhale, “But in Spanish, it translates to examinar cuidadosamente, which can also be read literally as to examine carefully.” She stretched her arms and continued on the path, “I’ve always wanted to examine this place.. it holds an unknown part of me.” Now, I feel her eyes looking at me as I stare blankly at the red ink. I grab her hand and bring it up to my mouth for a kiss. On the inside of her middle finger, there is an outline that looks like this country; a birthmark that is a constant reminder of a past she never experienced. She sighs and continues looking at the horse, clunking its way over to the mountain painted in the distance. She turns her head, stares for a second, and points straight towards the most violent figures: two white men shooting bows and arrows at each other. Above the sketch, a pile of cave moss is seeping down the wall. She grabs a pebble from under her feet and starts writing something at the bottom of the wall. Dear Grandchild, the shaky handwriting reads: I’m sorry this war lives inside of us. As we leave the cave, I watch her rubbing her hands together, bringing blood back into her palms, taking the numbing out of her fingertips. Lily Connolly Learn more about the prehistoric paintings of the Pachmarhi Hills at The Bradshaw Foundation. Lily Connolly is a recent graduate of the University of Tampa's undergraduate creative writing program. She has been published in several journals, including The Ekphrastic Review and Bending Genres, and she won the FCHC poetry award in 2019. You can find more of her thoughts on Twitter @lilyconnolly26 The Foot-Washer Lost in the Scottish National Gallery, my father finds a place to rest, surrounded by Poussin’s Seven Sacraments. He sits with his back to us-- a bald crown, broad back and creased plaid shirt. He is caught up in a picture, out of himself. Eight months after his sudden passing, I summon the painting on a screen: men recline around a banquet table. Casual glances and gestures pull my eye toward a bearded man, and a woman caressing his right foot. She is caught between bottomless grief and the joy of release from pain. The gleam of lamp-light on copper-coloured bowls, the way shadows slide, suggests the radiance floats somewhere high above the woman’s head. I’m sure it is she who bewitched my father’s eye. Dad wasn’t a religious man, and words like penitence and sacrament weren’t in his vocabulary; but he knew the signs of regret, and the look of one who finds peace, if not in forgiveness, then in giving yourself over to just one thing. David Belcher David Belcher lives on the north coast of Wales in the UK, he is a member of several poetry forums and writes almost every day. His most recent work has appeared in Prole Magazine, Poetry Bus Magazine, Ink Sweat and Tears, The Ekphrastic Review and Right Hand Pointing. David writes and reads poetry because he enjoys it, and for no other reason. He is not a very complicated person. Red River This story was inspired by On the Banks of the Red River, by Marcel Dzama (Canada) contemporary. Click here to view. The leaves of the red maple are more vivid today. Occasionally ichor wells up on the leaves, and when it becomes too thick to bear the tree bends and the liquid falls and enters the sandy earth, where it hides from prying eyes. Blood sprinkles the riverbank like spring rain. A young man, a boy really, struggles to reload his rifle. His fingers are slippery with fear and viscera. Around him are the bodies of fellow men and enemies. The air cracks with gunshots and shrieks. A soldier who has been kind to the boy raises his own rifle and points its death-end at a descending creature, its body furred and winged, its eyes sharp and its teeth dark. The soldier twitches his trigger finger but he is too slow, and the bat-thing reaches him and that is that. The soldier falls to the ground and is no more. The creature turns to face the boy but the boy finds his wayward nerves and thunders his gun and the creature falls to the ground, a weeping kiss opening upon its chest. The sand of the riverbank drinks deep. Red rain falls unending. Why this battle? Why pantomime a spring day in autumn? The boy doesn’t know: he just finds himself in the moment. Eyes, both living and dead, stare glassily at the ongoing fracas. All faces have become streaked with gore and grief. The body piles have grown high, and they are troublesome to trudge over. A creature with the face of the boy’s father lunges at him, gibbering backwards poetry all the while. The boy runs the man through with his bayonet, and the man’s head comes off and flies up to join the bats and other denizens of the wild. Many heads are up there, and although the boy doesn’t recognize any others, he knows they belong to the past. That’s just how it is on the riverbank. The boy’s fingers have been greased now, and he clicks and shoots with efficiency. The maples on the bank and the carp in the water are feasting. A head comes at him and he fires at it and it dissolves into gunpowder haze. This happens again and again. Time passes. The boy gets older. Spots and moles appear on his person. His vision blurs. He can’t feel anything but the wooden weight of his gun. Eventually, things begin to peter out. The creatures move less quickly. The soldiers die more slowly. The boy who then became a man and who is now an elder can no longer lift his arms. He tries to look for the face of his father but his vision fails him. All that is, is red mist. Everything, eventually, comes to a stop. The strings are cut. Lighting is fixed. The old man is a standing corpse, his veins full of suspended blood. The only moving objects are the red maples, as their leaves let loose spent life onto yearning ground. Carmen Peters Carmen Peters (she/they) is a writer and student living in Portland, Oregon. As a lover of horror and speculative fiction they aren't afraid to dive into the deep end, and as a sapphic trans woman she strives to express the magic of queerness. In their spare time they enjoy tarot, exploring strange nooks and crannies, and recalling nightmare fuel from her childhood. Their latest fiction can be read in Black Cat Magazine and in the upcoming Prismatic Dreams anthology from All Worlds Wayfarer. She can be found on Instagram @Carmen_Dreams_Ghosts. Join Meg Pokrass and Lorette C. Luzajic for an intensive microfiction workshop on Messy Love.

We will use some spectacular, strange, and sad stories from art history to inspire our own. Click here or on image above for more information and to sign up. “The online ekphrastic microfiction workshop I attended with Lorette Luzajic and Meg Pokrass was outstanding! The four day asynchronous workshop was a highly productive creative whirl of activity, where participants shared and generously commented on each others' work, in response to carefully selected artworks and fabulously inventive prompts. Both Lorette and Meg gave extremely insightful feedback and constructive comments on every single piece of work submitted. I was blown away, in fact, by how detailed their comments were; it was wonderful to have a dual tutor perspective on my writing. I'm new to writing micro and flash fiction and in addition to commenting on my work, the tutors generously offered advice on where to submit work and tips on writing in the genre. The supporting course materials were excellent and I have referred back to them several times, following the course. Although the participants and tutors did not meet face-to-face, there was a warm, welcoming atmosphere within the group and it was great to meet other microfiction writers and to feel part of a writing community. I cannot recommend Lorette and Meg's courses highly enough - they are a tutor dream team!” Jane Salmons, author of The Quiet Spy The Duc de Berry’s Hours after Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, by Limbourg Brothers (France), c.1412-1416 The calendar in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry shows the year. For time extends beyond the day’s hours, to the play of holiday and season. There is blue and red and green and gold on Earth, in cloth, in cup and plate, in January’s gifts. The sky’s in blue and gold. The duke is too. In February, there is snow. The sky’s in Pisces and Aquarius. A man is chopping wood. The sheep are in their pen. Come March, there’s plowing. On the castle keep, a dragon perches. Folk are at the work of tending to the vines. And then come April, the woods are in leaf. A gay company stands in the meadow: gold, magenta, blue. In May, these folk are mounted. They’ve arrived at the Hôtel de Nesle with its blue roof. The sky of June’s in Gemini and Cancer – they’re making hay. And in July, the sheep are in the fold to be shorn. August is a time for falconry, as in the field go scythe and wagon working. Come September, we harvest by Saumur or eat a grape. October’s sowing. In November, swine obey the swineherd under Scorpio. Then, come December, with a pack of hounds, we’ll see a wild boar run to ground. The year has played out in the Book of Hours and brought us back to Christmas. Off beyond the trees stands Vincennes. People do their work. The rich perform the task of gentleness, afoot or mounted in their blue and gold, as those they rule work in the fields. The air above maps out the zodiac. Another year, another harvest. And the sky is clear. John Claiborne Isbell Since 2016, various MSS of John’s have placed as finalist or semifinalist for The Washington Prize (three times), The Brittingham & Felix Pollak Prizes (twice), the Elixir Press 19th Annual Poetry Award, The Gival Press Poetry Award, the 2020 Able Muse Book Award (twice) and the 2020 and 2021 Richard Snyder Publication Prizes. John published his first book of poetry, Allegro, in 2018, and has published in Poetry Durham, threecandles.org, the Jewish Post & Opinion, Snakeskin, The HyperTexts, and The Ekphrastic Review. He has published books with Oxford and with Cambridge University Press and appeared in Who’s Who in the World. He also once represented France in the European Ultimate Frisbee Championships. He retired this summer from The University of Texas – Rio Grande Valley, where he taught French and German and coached men’s and women’s ultimate. His wife continues to teach languages there. Leonora Carrington’s And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur i. There were a cow-headed minotaura a ghost dancing toward us. The green moth-flower unfurling its leaf. Magic realism and alchemy. You and your pots of jam boxes of black tea. Pomegranate fruit. There’s no buttery, no Gothic hall, no debutante balls. ii. Crystal orbs that pull at the tablecloth gateway to the chthonic dreams. Past your house in Mexico City, the melons stuffed with larks past crushed sweet almonds, past the jacaranda you planted where surrealist artists in exile. iii. These white Xoloitzcuintles. These dog voices. iv. This is the asylum glass door the asylum gurneys: all those restrained with straps all those locked wards all orange blossom waters and vomiting. They say: Tell me about yourself. You say: My body parts lie on the floor. Some say: Madness! You say: The war. v. There to the left, is a kitchen, there the horned goddess. Her small hands, her cloven hooves. You want vermillion, earth colours. Ilona Martonfi This poem was first published by Lantern Magazine. Ilona Martonfi is a poet, editor, literary curator, and activist. Her latest poetry collections are entitled Salt Bride (Inanna, 2019) and The Tempest (Inanna, 2022). Writes in seven chapbooks, journals across North America and abroad. Curator of the Argo Bookshop Reading Series. Recipient of the Quebec Writers’ Federation 2010 Community Award. To follow her work, please visit her Facebook page. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|