|

0 Comments

the opening / the departure

The magician unveils his masterpiece: woman guillotined in half. Thrill flutters through the spine, like the splutter of angels emerging from an apple’s interior in the middle of intoxicated timberlands. Trees stutter as their tops await the delicate spectacle to begin: give up the world, keep the world from contaminating its sprites. When labia open into an infinitesimal fissure, angels freed into air, authorizes lungs, pink bellows that keep the body’s brush fires quickened, colors swiftly transitioning, like white to pink to crimson, the unfolding begins. First: inaudible rumble, then, tiny flitter into ripple, resonant rivulet tippling over smooth stone, seedlings breaking groundcover, rose petals unfurling. A stirring, a hiccup, a call to life, energy into wing veins, sap filling out, copied in multitudes, color patterns release the split fruit, the womb, the prison. Wings quiver like aspens, shiver out the crack. The apple pierced, eaten before the serenade drifts to the treetops, siren melody ting-tinging down like echoing cymbals: shing shing shing shing ––the winged exodus of micro angels seduced by the sensual cosmos. by Linda Stryker Linda Stryker lives in Phoenix, but sometimes in her head; her cat and piano are in there, too. She is a poet, teacher, radio reader, and tennis player. Her work has been appeared in several journals and anthologies including New Millennium Writings, Highlights for Children, ditch poetry, The Speculative Edge, Emeritus Voices among others We Stop in Front of This Picture of Death a drawing of a single war dead in a perfectly lit corner of the art museum we stop in front of this picture of death and view it from different angles caught in the aftermath not of battle but of the incomprehension of war not a metaphor or allegory you say or some abstraction of inestimable sadness but the austere depiction of loss no one famous or long remembered you say the subject must have been close to the artist a good friend or dear neighbour stolen in the prime of life how else such compassion guiding the mind and hand stepping inside the drawing so I can no longer see the present I ask from which war was the fallen soldier, of the victorious or the vanquished, and cry for the dead by J.J. Steinfeld “We Stop in Front of This Picture of Death” from An Affection for Precipices (Serengeti Press, 2006) by J. J. Steinfeld, copyright © 2006 by J. J. Steinfeld, and first published in Witness: Anthology of Poetry (Edited by John B. Lee, Serengeti Press, 2004). Used by permission of the author. Fiction writer, poet, and playwright J. J. Steinfeld lives on Prince Edward Island, where he is patiently waiting for Godot’s arrival and a phone call from Kafka. While waiting, he has published fifteen books, including Our Hero in the Cradle of Confederation (Novel, Pottersfield Press), Should the Word Hell Be Capitalized? (Stories, Gaspereau Press), Anton Chekhov Was Never in Charlottetown (Stories, Gaspereau Press), Would You Hide Me? (Stories, Gaspereau Press), An Affection for Precipices (Poetry, Serengeti Press), Misshapenness (Poetry, Ekstasis Editions), A Glass Shard and Memory (Stories, Recliner Books), and Identity Dreams and Memory Sounds (Poetry, Ekstasis Editions). A new short story collection, Madhouses in Heaven, Castles in Hell, is forthcoming from Ekstasis Editions. Written in—and to be performed in—the style, or an approximation of the style, of Billy Collins Before the canvas, he brushes words. Blue sky, red bandana, green boat, a thin pole to fish the Susquehanna in July. Although, he admits, he’s never fished the Susquehanna; perhaps, doesn’t even like fish, July, or red bandanas. I like Billy Collins. Actually, not the man Billy Collins whom I’ve never met except on YouTube with his balding head, half-smile wit, and perfect words pointing to themselves and, sometimes, to other things. Nor the Billy Collins who can mesmerize an audience with verbal acrobatics and flying twists that make me want to cry, How does he do this? in his drab suit-coat, no tie, and black glasses he yo-yo’s from podium to nose. Rather, it’s the poet who urges me to stand at my window each sunrise—although the sun doesn’t really rise in my backyard. It staggers through stands of Douglas fir, 55 minutes after the newspaper says it should. It hesitates, then shyly appears. Anyway, as I was saying when sun popped in, he wants me to ensure the neighbor’s cat has not made its presence smelt in flower beds near my back fence; and that someone is sitting at my table waiting to listen to my poetry over cereal bowls—or, in my house, over spelt bread spread with coconut oil, a healthy alternative to corn syrup and other suspect things corporations hide on well-stocked shelves. Which is not to say, raw milk wouldn’t sit on his table near a bowl of organic berries cultivated on the banks of the Susquehanna by fishermen’s wives, particularly those who hate fishy red bandanas and slime-green boats—while they wait for men with thin poles to row a sunset home. by Carolyn Martin Previously published in Carolyn Martin, Finding Compass (Portland, OR: Queen of Wands Press, 2011). Used with permission of the author. Carolyn Martin is blissfully retired in Clackamas, Oregon, where she gardens, writes and plays with creative friends. Since the only poem she wrote in high school was red-penciled “extremely maudlin,” she is still amazed she continues to write. Her poems have appeared in publications such as Stirring, Persimmon Tree, Antiphon, and Naugatuck River Review. Her second collection, The Way a Woman Knows, was released in February 2015 by The Poetry Box, Portland, OR. Ropes of Gold

She is bound to her beauty with ropes of gold. She glows in sunlight, her white dress stabs the eye. Her brothers, red with drink, have left her squeezed tight on this balcony. They will return when her bridegroom comes with a lily, a key and a cage. One is named for a cactus that grows in the desert, one for a lonely tree twisting on a headland above the sea. The third is named Cloud; his face a mist of breath and rain. All night she heard waters rise, sensed the giant eye that stares and stares as she stalks the courtyard of the moon. by Steve Klepetar Steve Klepetar’s work has appeared widely, and several of his poems have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net. Recent collections include My Son Writes a Report on the Warsaw Ghetto (Flutter Press) and Return of the Bride of Frankenstein (Kind of a Hurricane Press). Email him at sfklepetar@stcloudstate.edu. Leda and the Swan

A sudden blow: the great wings beating still Above the staggering girl, her thighs caressed By the dark webs, her nape caught in his bill, He holds her helpless breast upon his breast. How can those terrified vague fingers push The feathered glory from her loosening thighs? And how can body, laid in that white rush, But feel the strange heart beating where it lies? A shudder in the loins engenders there T he broken wall, the burning roof and tower And Agamemnon dead. Being so caught up, So mastered by the brute blood of the air, Did she put on his knowledge with his power Before the indifferent beak could let her drop? William Butler Yeats Mad Minerva

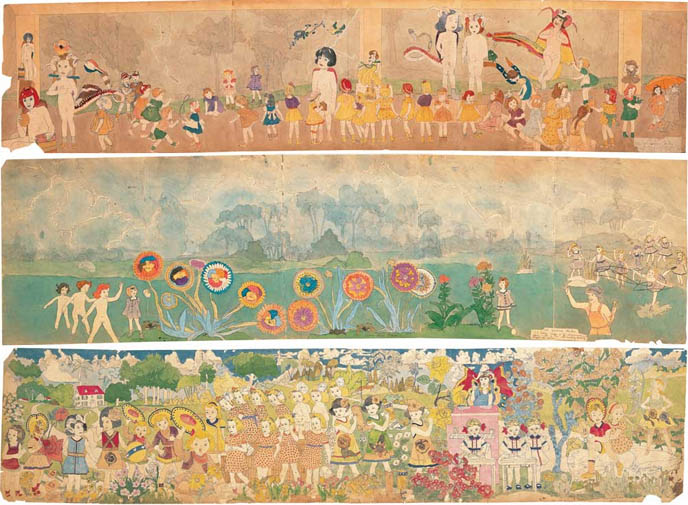

No, not wisdom born from the god’s brow, this is helmeted rage and scent of battle blood. How many times he rolled in his own sweat, calling down the spring rains. His face was thunder, his lips the parting of the sea. She broke his skull from the inside out, pouring through his pain. What did she whisper as she passed through his nerves and blood? Did she call him Father of my Spear, Giver of my Glancing Gray Eyes? Or did she leap from his brain with a shield and a thousand stratagems, an amphora of oil and a cunning net woven with skill from the sinews of the dead? by Steve Klepetar Steve Klepetar’s work has appeared widely, and several of his poems have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net. Recent collections include My Son Writes a Report on the Warsaw Ghetto (Flutter Press) and Return of the Bride of Frankenstein (Kind of a Hurricane Press). Email him at sfklepetar@stcloudstate.edu. Henry Darger spent most of his childhood in orphanages and during his life was seen only at work, as a janitor, and Catholic mass. Otherwise he retired alone to his rented room. After his death in 1982, his landlords found tens of thousands of drawings, paintings, and writings, mostly strange fantasy stories about children and wars between good and evil. One of his novels was over 15 000 single spaced pages long- it was called The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion. There were thousands of illustrations to accompany the book.

|

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|