|

Unfurl the Sail

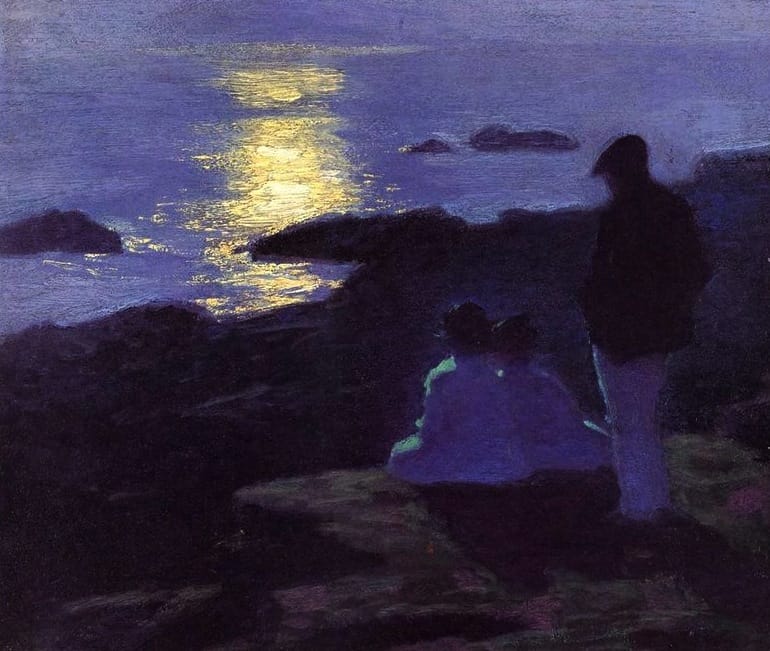

"I'm going to disappoint you. But you knew that already." My wife, Jocelyn, said this to me so many times that it seemed like a stock phrase like, "How are you?" or "How was your day?" I stood in the shadow of my two daughters, Sophia and Olivia, as they were sitting on the rocks near the sea looking at a reflected strip of sunlight. Olivia gently pressed her head on Sophia's shoulder. They told me that they pretended the strip of sunlight was a runway and they were waiting for their mother to arrive in her private plane. She would step out and give us a big hug. While we were waiting, we traced the flight of a sea gull flapping her wings over the water. She swooped down; beak dipped in and bobbed up and caught - nothing. Would her babies be disappointed when she returned to the nest with no fish? After several hours of waiting, they forgave their mother by saying that she'd missed her flight, her flight had been delayed, she'd arrived at a new destination. Jocelyn, meandering through an unknown town, talking to strangers, adopting a new family - these thoughts chilled me. Or, perhaps, she was arriving by boat, a longer journey. She'd been captured by pirates and was forced to maraud neighbouring islands. The smoke that we saw far off was her doing. Or she might arrive riding on a dolphin's back. Or she was afraid to unfurl the sail and come home to us. My daughters were not the only ones with an imagination. What I didn't tell them, as of yet, was their mother was lost. But they probably knew already. After the birth of Olivia, Jocelyn's flamboyant behaviour became apparent. She'd flutter around the kitchen leaping and grabbing at imaginary objects. Then less than five minutes later, she'd be sobbing on her pillow pleading with me to kill the spiders crawling up the wall. I'd left my job at the firm. We'd packed and moved to a bungalow high on the hill overlooking the sea. The milieu - the breeze off the sea, the warmth of the sun, the sound of the sea gulls - delighted Jocelyn. After we'd put our daughters to bed, Jocelyn and I would sit on the veranda, fingers interlaced, listening to John Coltrane. We would dance; I would twirl her around and around until we both collapsed from exhaustion. After reading the Ghost and Mrs. Muir for the fifth time, Jocelyn called our home Gull Cottage at Whitecliff-by-the Sea after the house Lucy and her imaginary ghost lived. The dream ended - tears streamed, the fear of everything gripped her again. I dreaded to think that she'd fling herself into the sea. The doldrums returned and shrouded her face. I commiserated as best as I could. She glanced up and said, "Kevin, I'm scared." The green-blue hue of the sea transformed into the green sterile walls of a hospital, a hospital that would be her home for two months during shock treatments. The sound of her screams as they wheeled her into the operating room wounded me. Afterwards, despite the vacuous stare, I knew Jocelyn, my wife and mother of my daughters, was stranded in a place only she knew. I sat by her bedside reading to her about Captain Greg telling his sea adventures to Lucy as she was writing them down. For now Jocelyn is off on a journey in her mind. Who knows, maybe one day she would unfurl the sail and come back to us. We will be waiting on the rocks by the sea, waiting for one more twirl on the veranda. Matthew Hefferin Matthew Hefferin enjoys writing short stories, flash fiction, and prose poetry. He has taught English as a Second Language and U.S. History to non-native speakers of English.

2 Comments

The Wind From the Sea

The sheer window curtain bellies like a pregnant Muslim woman in her dupatta, filling with secret life from beyond the horizon. Fine incisions written as tatters say the sea has been restless for ages. The tea kettle outside the painting purrs today will start out calm. It is enough to know these things without having to say them. Wyeth’s painting holds them before us. Beyond the curtain is a road leading to the sea, to whales and fishermen with sore red hands. And to you, and to me. Craig Brandis Craig Brandis lives and writes in Lake Oswego, Oregon. The Day Death Died

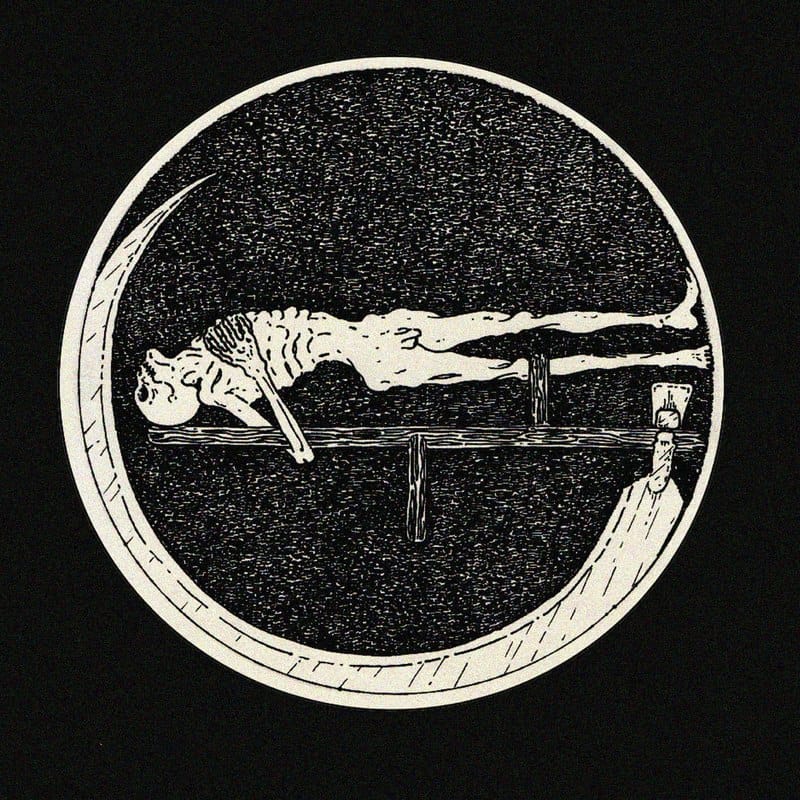

It was widely known that Death had been ailing for some time. Its poor health had made it rather slipshod in the execution of its duties. Whole generations were being taken away in the flower of their youth, while other people were living for an extraordinarily long time - over 400 years in certain cases. For a while Death hovered in a half-alive condition, with one foot in the grave, and mankind held its breath, fearing Death would rally and make a complete recovery. And then the day came when Death breathed its last and nobody could believe their good fortune. It was hard to grasp that Death no longer dwelled in the world, and that one’s life would never again be burdened with the ever-present spectre of extinction hovering nearby. No one would have to grapple any more with the problem of incorporating one’s own demise into their lives. The most eminent pathologists of the land were assigned the task of performing an autopsy on Death. Their unanimous conclusion was that Death died of natural causes. What nobody had suspected was that Death possessed a finite life span. Everyone had always assumed it would live forever, yet it too carried within itself the lethal seeds of mortality. The next most pressing issue was the burial of Death. Issues never considered before needed to be addressed urgently, for the world wanted to be sure Death really was dead and would not rise again. Where should the funeral ceremony be held? According to which religion’s rites should the memorial service be conducted? Who should give the eulogy? Where to entomb it? The matter of whom to invite to the service proved to be the most intractable issue of all. A certain number of tickets were reserved for those most deeply affected by Death's passing - morticians, grave diggers, psychotherapists, blues singers, goths and horror film directors. Otherwise, it was nearly impossible to determine who was genuinely grief-stricken and who only wanted to attend the ceremony so as to be a part of this historic occasion. Eventually, all of these matters were resolved, although not to everyone’s satisfaction, and the world gave Death the sending off it deserved. Straight after the funeral, the world kicked up its heels and celebrated. When the unbridled, hysterical wave of joy at being liberated from Death's tyrannical rule had abated, people sobered up and recounted the ways Death had helped out in the past. They recalled with fondness Death’s unique ability to provide clear-cut and definitive solutions to any inextricable, inflexible or abstruse problem of existence; its unmatched faculty of erasing all pain, shame and misery; the way it was always there to readily and obediently offer its helping hand to anyone who would ask for it and the way in which it brought equality to the world and granted perpetual rest to the weary. Religions could no longer survive without Death, for their appeal and authority derived from the promise of ideal and everlasting existence in the next world and from their expert knowledge of the nature of the Afterworld. New religions arose, prophesying that one day mortality would return to Earth and the virtuous would be rewarded with Eternal Death. Mankind recognised how fundamentally it depended upon Death’s existence for the preservation of social order and peaceful international relations. Given that capital punishment and armed conflicts ceased holding any threat to a person’s life, nothing stood in the way of lawlessness and immorality in human affairs, and countries went to war on the slightest pretext. Life soon lost its meaning, for Death had been needed to provide the contrast that distinguished being from non-being. Without it, existence became unrecognisable, a grey shadow of its former vibrant self, and to be alive was now an unendurable, yet inescapable, fate worse than death. Each human being was forced to find the strength and the courage to face a baffling future in which the saving grace of demise was no longer present. Only then was it realised how inextricably Death had woven its fateful thread into every aspect of man’s existence and how much had been irremediably lost the day Death died. Boris Glikman Boris Glikman is a writer, poet and philosopher from Melbourne, Australia. The biggest influences on his writing are dreams, Kafka and Borges. His stories, poems and non-fiction articles have been published in various online and print publications, as well as being featured on national radio and other radio programs. Not to be Reproduced

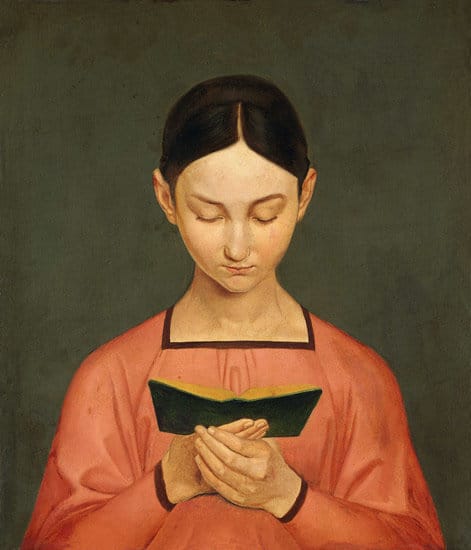

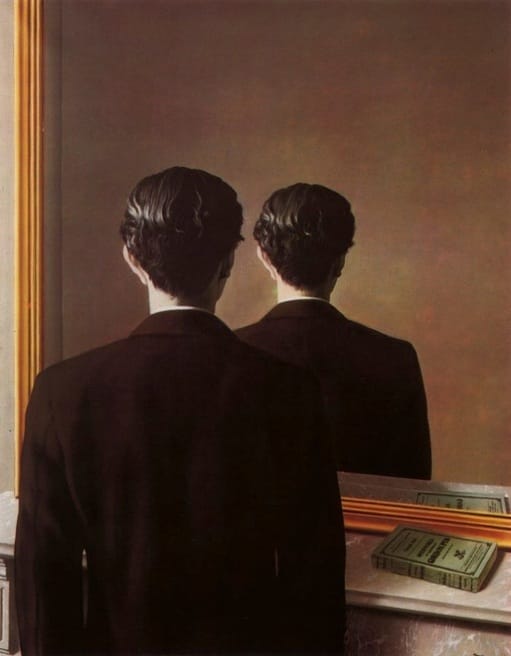

Life obliges me to do something, so I paint. – Rene Magritte Poet. I have seldom read you, but I have seen something of the infinite abyss in you. Strange, how I talk to you now, as if in limbo, studying the silence that envelops you. One can’t help, but wonder what’s going on in that beautiful, surrealist head of yours, two years ahead of the war, three years ahead of Trotsky’s assassination in Coyoacan. I’m not certain if what I see is a portrait of a poet, or the mind of a genius. When I look at the back of your head in the mirror, I struggle with writer’s block to say anything more meaningful than: Ceci n’est pas une pipe, which really translates as: ‘this is not a portrait, but a lesson in portraiture, as much as it is a lesson in life.’ I wonder if you agree with your painter friend that art is equal to the mysteries of life? Like Rene, I conceal nothing. My only hope is to look the abyss in the face without prejudice. Mark A. Murphy Mark A. Murphy’s studied philosophy as an under-graduate and poetry as a post-graduate. His poems have appeared in over 160 magazines world-wide. Jerome Jerome? You sure you want to go up there? Well, you’ve come this far by boat -- that couldn’t have been easy, and you do have a determined look about you. The road to the place where he lays his head, well, it’s two day’s journey from here. He gets the occasional letter, and I’ve had to deliver a few to him up there in the hills. But he’s kind of irascible, that one. I can’t imagine he has many friends. There’s that fellow down in North Africa, Augustine I think his name is, writes to him now and then with some question or other about the scriptures. Jerome always wants paper, says I should bring more paper with me whenever I come, so he can keep translating his holy books. Who knows where he gets the money to pay for it? But he’s never owed me anything, always seems to have a few coins about him. Well, it’s not like he’d spend it on anything else, right? Never seen a woman up there. Doesn’t keep much to eat or drink. Where he lives, it’s a cave mostly. You could call it a hut, but it doesn’t even have a proper wall. The rain seeps in, the wind whistles through. But believe me, it hardly matters to him. He keeps a crucifix before him, and a skull, his memento mori he calls it. Once I found him talking to a lion, pretty foolish that, and I told him, I’m not coming any closer! But he whispered something in its ear and the thing padded off. For a good part of the way it’s farmland, and that part’s not bad. You’ll go past a lake too, where there’s a mill. You might see a few carts, coming and going. Not far from there is a monastery where they’ll put you up for the night and help you get started again in the morning. But soon the road gives out and from there it’s just a path, Lonely, deserted. Keep your wits about you, friend -- some travelers were beaten and robbed up there recently. You’ll come to a footbridge that crosses a stream and from there it’s about an hour. Eventually that path comes to an end, and that’s where you’ll find Jerome. He’ll probably be praying when you get there, he might not even notice that you’ve come… Fred Guyette Fred Guyette is a Reference Librarian at Erskine College in South Carolina. "In the place where I work," he says, "I walk past a print of "Jerome" by Patinir (1524) everyday. I often stop for a moment, and find something in the landscape that I haven't seen before. I try to imagine... Who would go and see Jerome? How would they get there?" Break

The night before your plane left, I broke my left pinky toe — or as the doctor diagnosed, my fifth metatarsal. I was getting out of the shower, wringing my ratty hair in a towel, when I noticed the bathroom rug was the same colour as your eyes. I buried my eyes in the damp towel, and slipped on the ceramic floor, somehow wedging my toe between the bronze pieces of the tub’s drain. “Just go to the doctor,” Jasmine urged, bagging ice cubes from our freezer in a Ziploc for me.“ Tomorrow,” I told her. “Tomorrow” was what you told me after I asked when your flight was. I wasn’t expecting that. I cursed at you for the first time, slamming the door of my apartment behind you, between us, like the Equator would be once your plane landed. “I didn’t know how to tell you.” Your spearmint-coloured gaze was wet, sparkly; mine was frozen. I glared past you at Jasmine’s National Geographic map plastered on the wall. I traced my eyes from Los Angeles to Bolivia, and somehow, down my cheek, emerged a river. You felt like you had to go now, that you needed to see the world and find yourself, by yourself. Joining the Peace Corps would be the answer to your happiness. I’d spent two years under the impression that I was. You hadn’t even told me you’d applied. There was nothing peaceful about that. I numbed my foot with ice since apparently the break was too small to cast. Meanwhile, Jasmine tried to distract me with Netflix. “You need to get out of this apartment.” It was three days after you’d left. I hadn’t been out since the doctor’s appointment. She peered across the couch at me. I didn’t like the nervous pity that blazed in her wide eyes. “Fine,” I handed her the ice and hobbled out the door. The doctor had advised me to take it easy; I figured driving was okay. You’d figured graduating early and teaching English in South America was okay too. I punched the steering wheel of my car, horn screeching. I was parked somewhere on Main Street. For whatever reason, the coffee shop here was the only place I could think of going; it was the one we’d found when we first started dating, the one with the vibe you’d decided you didn’t get. Limping crutch-less through the door, I was stopped by a man, probably in his sixties, with sea-blue eyes a little darker than yours. “You look like you could use a Scott Jones original.” I’d forgotten the place was like an art studio for self-proclaimed abstract philanthropists. He held up a large watercolour pad, flipping through several canvases, each adorned with its own array of vibrant, fading lines. I asked if they were tree roots. He said if I saw tree roots, then tree roots they were. I stared hard at the one he lingered on; his stained hands, cracked with dried paint, tore the painting from the rest of the collection and gave it to me, free of charge. I ordered a chai latte and wondered if you’d see tree roots too. “That isn’t beautiful to me,” you’d retorted, tugging my hand away from a copy of Mark Rothko’s “Number 61.” There were three lines in the painting — pigments of indigo, eggplant, and that post-sunset, full-moon sky glow. It was the time we’d stumbled upon the coffee shop after getting pizza up the street. The walls were cluttered with abstract works from floor to ceiling, some replicas of more famous pieces, others originals donated by the local artists who congregated here. I asked you why it wasn’t beautiful. You told me art had to have a purpose, that beauty should make you feel small. On the drive home that night, you told me I was beautiful. I didn’t mention that sometimes you made me feel small. I looked up Rothko’s website after you’d dropped me off at my apartment. The painting was inspired by staring at flames for too long. My eyes searched the brick walls for it now, but it was gone, replaced by a Picasso and numerous variations of the tree roots I’d been given. I scrutinized the swaying, pigmented lines, wondering what had inspired them. I carried the sheet back to Scott’s table. He set down his paintbrush as I approached, eyes reflecting the same pity Jasmine's had. I ignored it. "What inspired this?" I held up the tree roots. "The subconscious," he said with a smile, stirring his eight-ounce cup of mildew-coloured water with a brush. "Do you think your paintings are beautiful?" I hesitated, hoping he wouldn’t take it the wrong way. He told me I was a beautiful person. I asked if I made him feel small. "Beauty should make you feel big and small at the same time." "Huh," I muttered, staring at the canvas. I thanked him as I walked out the door. “Thank you for being a lovely person,” he said. I drove home and lit a candle; I was big enough to blow it out, yet small enough to get burnt. I couldn’t decide which was worse, getting blown out, or burning someone. I placed the painting on top of Jasmine’s dresser and Googled a picture of “Number 61.” My printer fed it to me in black and white. I taped it to the wall above the dresser, beside the tree roots. I knew that forests and fires were not supposed to go together, but somehow these did, like we used to. I’d leave them side by side for now. I immersed my purple pinky toe in another bag of frozen cubes. This was the only thing the doctor had prescribed. I don’t think he understood that my foot wasn’t what seared relentlessly. “You’re just gonna have to be patient,” he’d said. “It’ll heal in no time.” Shelby Zurcher Shelby Zurcher is an aspiring English teacher studying at Azusa Pacific University in Azusa, California. Originally from Portland, Oregon, she is inspired by the beauty of nature as well as the beauty represented by the diversity of human beings. Feel free to check out her blog at https://wordpress.com/posts/shelbyzurcher.wordpress.com. |

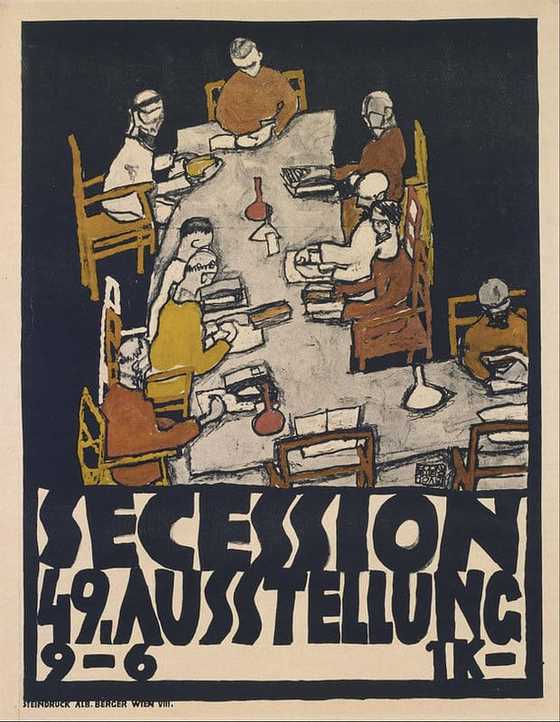

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|