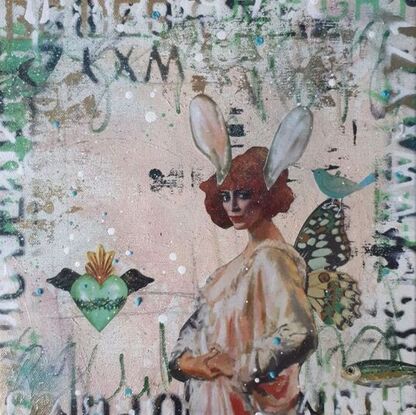

Congratulations Cyndi MacMillan!!! The Ekphrastic Review Made It Into "Best Microfiction" 2021!!!!1/31/2021 Bravo to Cyndi MacMillan for her microfiction piece, "When Alice Became the Rabbit."

Congratulations! This short was published in October and was one of The Ekphrastic Review's nominations for the Best Microfiction Anthology. It was only our first year nominating for Best Microfiction! Cyndi's story will be published in the Best Microfiction 2021 anthology, and we will post when it's published. The editors at Best Microfiction are Amber Sparks, Meg Pokrass, and Gary Fincke, and the judge this year was Amber Sparks. Here is the list of writers, stories, and literary journals that will be included in the upcoming anthology. Congratulations again, Cyndi! With the amazing talent of our writers, we are going to do this again and again!

0 Comments

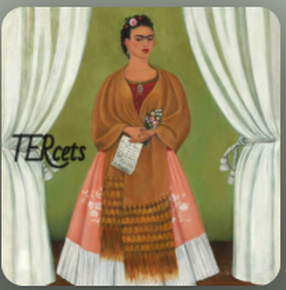

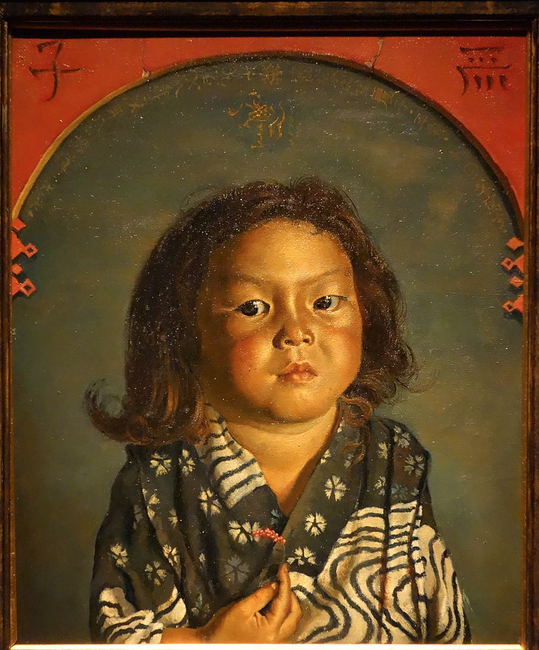

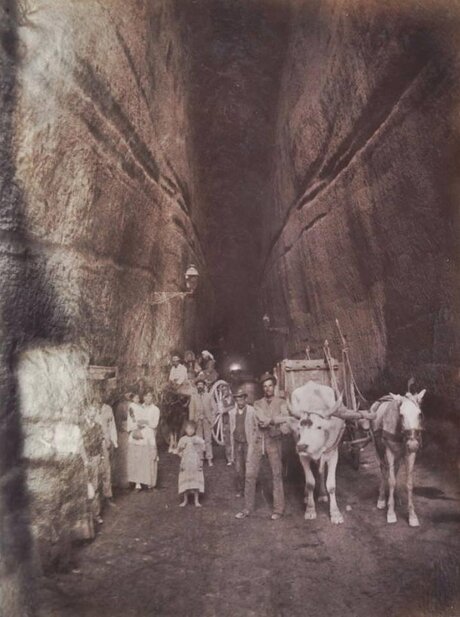

Ode to Félix González-Torres There lay the body in all of its glory. A soft earlobe, blistered fingertips, a single eyelash has dropped down to the chin. A little boy would come and take a piece-- unravel the paper slowly—giggle because it is sweet. And he is right. It was. But at this moment, I do not wish to take one. When it is not mine to take. Winter came, but you were kept warm by the simplicity of touch, the rigidity of a tongue pressed against yours, sweat accumulating down your back. Slowly, the sweat became a sopping wet jacket you had to keep on. A jacket for two: you shared the same dwindling ferocity, the same wrapping paper in your pockets, kept buttoned up. But love, you see, lingers past the cellophane. I think of Hujar and Wojnarowicz—unabashed, relentless—dancing on the boardwalk at noon. Love bouncing in their plaid pockets, oozing down their esophaguses, growing into saplings, only then into wilting trees. Loving like this is futile, weakening—and still everything you did. I see the boy’s blood spilt out on the sidewalk. His face beaten and his heart laid stripped on the sidewalk. You could never know the strength of a tongue until you bite down on it, or the fragility of a lover’s touch until he is gone. What is left of the body gleams, untouched. I think about you until I am jaded, until I give in. Sophia Liu Sophia Liu is a Chinese-American writer and artist from New York. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in Sheila Na Gig, opia, Augment Review, Bitter Fruit Review, and elsewhere. She has been recognized by the Scholastic Art and Writing Awards, the National Council of Teachers of English, Cisco Writers Club, and Hollins University. She volunteers as a writing teacher for the Princeton Learning Experience and has taught students in the United States and China. She wants a pet cat. Portrait of Dora, Recovered* You smile your calm blue smile Deconstructed Beneath your fabulous fascinator Under the jaunty orange and yellow bow Glimpsed through Picasso’s prism Artist and lover Your black-rimmed eyes intrigue Shape shifter Kidnapped Stolen from a royal sheik’s yacht Passed hand-to-hand You disappeared Underworld traveler Collateral For twenty years In drug and gun deals Guernica’s Cassandra Trafficked Feared dead Consumed by fire or rotting in a garbage dump Weeping Woman Yet thieves could not destroy you Too mercurial to hold They sent you back Muse To the “Indiana Jones” of art detectives Who hunted you Who said he had to have you on his wall for just one night Temptress Your blue smile still calm Your colours explode like a nova across cyberspace Your kaleidoscope whirls Diva You once said, “All portraits of me are lies.” Elizabeth Fletcher *Picasso’s portrait of Dora Maar (painted in 1938, but never before exhibited publicly) hung in Picasso’s home until his death. In 1999, it disappeared from a private collection until its recovery in 2019. Maar, a noted surrealist photographer and landscape painter had a relationship with Picasso for almost 10 years. Elizabeth Fletcher’s poems have appeared in The Schuylkill Valley Journal, The Scarlet Leaf Review, Ariel Chart, Tiny Seed Literary Journal, The Lost Orchard Anthology, and Plum Tree Tavern. Her nature essays have appeared in The Philadelphia Inquirer. She has a B.A. in English from Hamilton College and a Master’s degree in Technical Communication from Drexel University. She was a writer and editor for a medical education company for many years and is now a freelance writer. Words cannot express the pride, joy and gratitude we feel to Brian A. Salmons for dreaming up this podcast for The Ekphrastic Review and making it happen. We are thrilled to announce the second episode is up. TERcets Episode 2 https://open.spotify.com/episode/41i1kgskYqB7s8r7unqBjw?si=oWKjairJSf-K00rfpiILig TERcets is a literary podcast by The Ekphrastic Review. Listen to your host, Brian Salmons, read three pieces selected from our website, ekphrastic.net. This episode features poetry by Jonathan Yungkans, Sarah Antine, and Jane Frank, all inspired by Frida Kahlo. The Ekphrastic Review is an online journal devoted entirely to writing inspired by visual art. Our objective is to promote ekphrastic writing, promote art appreciation, and experience how the two strengthen each other and bring enrichment to every facet of life. We want to inspire more ekphrastic writing and promote the best in ekphrasis far and wide. Theme music is by Judadi - https://soundcloud.com/judadi - specifically, songs from his "Earlyworks" - https://archive.org/search.php?query=farr+earlyworks. The other music is from the Field Trips, the Kokusai Bunka Shinkokai, and Adam & Alma. The cover art is Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky, by Frida Kahlo (1937). Editor's Note: Thank you to everyone who participated in the Maria Martinetti challenge! The accepted responses in poetry and flash fiction are below. It is always a joy to see how so many voices approach an artwork and what it inspires in their words. The biweekly ekphrastic art prompts have become something of an institution here at The Ekphrastic Review. Each artwork is carefully selected with the hope of taking your imagination to new places and challenging you in your ekphrastic practice. It is our hope that we can show you art for the first time as well as bring the chance to write about universal favourites. In order to maintain the pace of biweekly art prompts, this year we have stopped sending out sorry or yes letters for the challenge submissions. Since the responses are posted one week after the deadline, you can find out whether your piece was published easily in a timely manner. This is in no ways meant to be impersonal- it is simply where we saw the best opportunity to save on editorial time, because writing an extra one hundred to six hundred notes a month is a major task . We thought this over carefully, and feel the time is better spent putting the challenges together, posting our writers' work, orchestrating new projects, and promoting our journal and writers on social media, etc. Understand that we can only use a fraction of the submissions we receive. We strive to faithfully showcase our regular contributors' works and give just as much space to new voices, too. We like to show works that demonstrate a range of perspectives and stories on the art as well, in order to give us new ways of looking at each painting. It is always tough to choose a few from many! You still have a week to try out the current challenge, Two Sisters, by Chausseriau. Click here to see that painting and the instructions. We look forward to reading your submissions on this stunning painting. While we are together, let me remind you about our awesome new TERcets podcast. We are most grateful to Brian A. Salmons for dreaming up this project and turning it into a reality. He has just finished the second episode! He reads Sarah Antine, Jane Frank, and Jonathan Yungkans. Check the podcast here! Please share the challenges and these responses far and wide on your social media. It is a generous act that brings readers to our amazing writers. We are most grateful for it. love, Lorette ** The Distaff, the Spindle, and a Cradle Full of Purkinje Fibres I recall Grandma Smith’s spinning wheel, its parts. My mom kept the pieces in a cardboard box. Where is that container? I think it was left in the garage-- the one constructed out of limestone by local builders, the one my dad designed out of care, devotion, and future plans of an apartment, a second-floor living space for us, his children, and for forthcoming generations. I wonder if it still stands, or has the new owner demolished it? He did mention the demolition of the house—the one made of rusticated concrete blocks and adorned with leaded beveled glass windows, the one that’s situated on a bank near the Rush River. And what about the adjacent acreage across from the river? For some, a purse bulging with bankrolls and Benjamins takes precedence over everything, including relationships. My focus shifts to the serenity of the woman in the painting—the one who spins flax, sits near a cradle, where a colourful textile drapes atop its handle. Here, I picture my Great Grandma, Karin. She wears the traditional Swedish folk costume. Her left arm hugs a distaff as her left-hand guides the unspun fibers toward her right and to the rotation of the spindle. Beneath the cradle’s covering, I imagine an infant, Edith Malvina, my mom’s mother, my grandma-- the one born in Filipstad, Värmland County, Sweden, the one orphaned as a young girl. My ancestry speaks through its handwork. It echoes with the cellular memory of craft and creation, resonates with the single, half double, and treble crochet stitch, knit and purl, whispers weft and warp, breathes with needlework and embroidery. A tapestry of Purkinje fibres weave amid the inner ventricular walls of our homespun hearts. A box of spinning wheel parts, a stone garage, a block house, and a river bestows textural reminiscence. This imagery rocks and flows inside a cradle of love—the one I visualize, where lullabies resound and sweet dreams repeat for my dad, mom, brother, and the deceased relatives, the one where I hold my sister, Mary, and my son, Andrew, in light, as I do the entirety of my living relatives, the one where I surround humanity, Earth and its fragile creatures in prayer. Jeannie E. Roberts Jeannie E. Roberts lives in Wisconsin, where she writes, draws and paints, and often photographs her natural surroundings. She’s authored four poetry collections and two children's books. As If Labyrinth - Pandemic Inspired Poems is forthcoming in May 2021 from Kelsay Books. She’s listed in Poets & Writers and is poetry reader and editor of the online literary magazine Halfway Down the Stairs. To learn more, please visit www.jrcreative.biz. ** The Fate Perching Madonna Cradle before Flax strick upheld You smile Mythical artistic rendition Of life held on the edge. Toil unappreciated Each thread, golden Time spins Producing wisps of gossamer If you can. Yet, in this you show Labour, unstinting From edge to edge Dawn, labour, dusk Dawn, labour, dusk The loom of life Weaving through aeons. Your next shackle A wheel to bind and break A machine to hold you home Locked down textile worker (Echoes of reality That fashion treads on the unnumbered) As it has, So it will be, And the flax you spin Retts your linen shroud. Sarah Foster Jarden Sarah Foster Jarden: "I love reading, but for the 40+ years after leaving school I only used normal everyday written language not straying into poetry or prose as a hobby. I began writing at the start of lockdown in March 2020 when a friend encouraged me to join a Haiku group on Facebook and it was a really great discipline, writing a haiku a day. I maintained this until I returned to work and have joined a creative writing group which meets virtually fortnightly. Both have been run by the same wonderful lady, thank you Siobhan and all the supporting cast in the groups. I am also a spinner, of flax and other fibre, a truly wonderful joyous craft. I teach spinning, do historical reenactment and enjoy demonstrating spinning at local shows and events (when they are on). The other bit of my life is spent working in Mental Health Services." ** Spinning Flax Aqua coral clay tiled floor Arched blue stoned face The lady spins the flax Spear like As her eyes are mesmerized Wearing the gold laced sash On white breasts With a smile upon her Face Brown coloured hair Encased with milky white Sleeves That bleed crimson red The flax is spun Above the basket With blue tan white grey black stripes That bridges the space The space on the lap That holds the blue white red-gold; red blue cloth Steps set in time have no wish Just stones set in eternity Her blue eyes in trance Nose mouth a fixed Pale skin red lips The flax she spins Is full of all grace Amen James N Hoffman James N Hoffman studied psychology and philosophy. He enjoys writing what he calls "colour poetry" because he cannot paint. He lives with his wife in Ocean City, Maryland. ** Spinning A Dream Sweet dreams, my little child! But when you wake, Please do not think the bottom of the stair Is where we are ordained to stay. We'll make New lives for us across the ocean where New York now beckons. What will Mama do? I may not get flax-spinning work full-time. No matter! I'll take any job, so you Get educated, and we both may climb ... A steamship sails next week, and once we're there, Dreams will not be just dreams for you and me. Remember how your uncles climbed the stair: Embarking for the New World was the key ... America awaits. But till we steam, May you sleep sweetly, while I spin our dream! Mike Mesterton-Gibbons Mike Mesterton-Gibbons is a Professor Emeritus at Florida State University who builds game-theoretic models of animal behaviour. His acrostic sonnets have appeared in Autumn Sky Poetry Daily, the Creativity Webzine, Current Conservation, The Ekphrastic Review, Grand Little Things, Light, Lighten Up Online, Oddball Magazine, Rat’s Ass Review, the Satirist and the Tallahassee Democrat. His limericks have appeared in Britain’s Daily Mail. ** In the Courtyard In the courtyard, I sit and spin linen thread, From flax holding distaff high, and dreaming. Dreaming of a time when my arm will not grow heavy from holding flax, when the formed thread will be enough, when I will be enough, when will this thread finish, when will my thread end, I ponder all these things. Will I ever be able to sashay into this courtyard climb the narrow steps to the roof of our cottage look out over the village in clothes made for me from flax I did not spin from toil not mine? My arm grows more tired, heavy. My weakening legs agree-- Dreams are what sustain. Joan Leotta Joan Leotta tells tales of food, family, and strong women on page and stage. Her love of art drew her to ekphrastic writing and she has written for this journal and told ekphrastic tales at many museums, including the Phillips Gallery. Her chapbook, Languid Lusciousness with Lemon is out from Finishing Line Press. ** Tender Fingers Held the Touch So much colour, so many lines-- the rugged upward steps. She twists the yarn and twines the strands with delicate fingers poised, with wrists lent to the lengthy task Here is beginning, perhaps without end Here is doing what is expected, a way to reach beyond the daily, to extend one’s touch, other work neglected, to focus on this lengthy task No clouds adorn this flaxen scene for on her face a gentle smile; placidly she sits between two baskets, leans and rests awhile, then resumes her lengthy task And often there must appear to her memories dear, the work done with sister or mother sitting by, another day of labor, another bit of work begun, a twist, a turn, a lengthy task And mother would have taught her how-- for that is how we learn; and she can still remember now, her mother’s face upturned-- her praise tendered for lengthy and successful task Carole Mertz Carole Mertz, a semi-retired musician, enjoys reading and writing poetry, especially ekphrastic, of late. She publishes poems, essays, and reviews at such sites as The Ekphrastic Review, Eclectica, League of Canadian Poets, Main St. Rag, Prairie Light Review, The Bangalore Review, and World Literature Today. Carole resides with her husband in Parma, Ohio. ** Ariadne I know by the absence of your tears and the absence of blood on your hands as you adorn your solitude with the silver needle the gods had sewn in your skin as compensation for exile it is a test... to find the eye of the needle slip through unseen and hand them the end of the thread. I also know when the gods abandoned you so early to your as yet unimagined designs you picked up the skeins of their divine endowment passing the invisible thread through the unseeing eye till it tore unwinding the red-flecked iris from the jet black pupil of fear and without blinking once began to fashion from the songs of the exiles you and I alone can hear an ornate grammar of survival... whose intent was so exquisitely clear even the gods knew fear. How could they know where your designs would lead what lies they would unravel what truths they would reveal what beauty ? Helen Albright ** Maria Martinetti Paints My Great Great Grandma Carlotta Sanguinetti maybe she’ll give some colour to your cheeks add a blue door to that black and white portrait in the hall your face moon wide as bread squashed into a suitcase. maybe she’ll give you some romance, not a bald hard working husband who dies when he falls down the stairs. but that’s after you’re gone actually, you died so many years before. did you still tongue the language from the old country? we can’t call it Italy or Italia because it didn’t exist then. there was no country. but she’ll recognize something in you, the babies in baskets, the stone at your feet. instead of a spindle she’ll paint the way you lean towards the dough of the raviolas as you unroll its blank map onto the board. slick floured sheet of promise, imagine the crushed spoon of herbs, ping, left in neat rows. imagine you leaning in to follow with another sheet made over the bed of that one, you can hardly stretch your arms wide enough to make all this food, sleeping pockets of the traded earth. Francesca Preston Francesca Preston is a writer and visual artist. Her poems have appeared in Crab Creek Review; Malus; one sentence poems; Phoebe: a Journal of Literature and Art; Stonecoast Review; Walrus; and elsewhere. She lives part-time in a ghost town settled by her Ligurian ancestors. francescapreston.com ** Soothing Manual labour Hard work for delicate hands Baby at your feet Spinning flax with tenderness While humming a gentle tune Rose Menyon Heflin

Rose Menyon Heflin is an emerging poet from Wisconsin. She is also an avid artist and photographer who loves nature and travel. Her camera is named Nessie after the Loch Ness Monster, and her machete is named Carmen after the opera protagonist. Among other venues, her work has recently been published or is forthcoming in Asahi Haikuist Network, Bramble, The Closed Eye Open, Eastern Structures, Haikuniverse, The Light Ekphrastic, The Parliament Literary Magazine, Plum Tree Tavern, Red Alder Review, Sparked Literary Magazine, Three Line Poetry, Visual Verse, and The Writers Club. She strongly prefers trees to people any day of the week and twice on Sundays. ** Spinning a Web Mesmerized, as a little girl I’d watch Mama in this hand ballet for hours – couldn’t wait to learn it myself. It looks like you’re playing a harp! I said, and she invited me to sing and dance along. There’s no time for dancing now. I prefer working outdoors, nodding to neighbors passing by and making sure the new music teacher sees me. Last month, Signore Rossi stopped to ask, What’s that tune you’re humming? I smiled and said, A Tuesday song. I just made it up. Brava! he said, though he hurried away. Each day I see him lingering longer at the fountain, so I lift my voice to meet him there. He pretends not to look my way. Alarie Tennille Alarie Tennille was born and raised in Portsmouth, Virginia, and graduated from the University of Virginia in the first class admitting women. For Alarie, looking at art is the surest way to inspire a poem, so she’s made The Ekphrastic Review home. She was honoured to receive one of the Fantastic Ekphrastic Awards for 2020. Alarie hopes you’ll check out her poetry books on the Ekphrastic Book Shelf and visit her at alariepoet.com. ** Upon a Time She is not the daughter of a miller trying to impress the king. Neither is she daunted by the spindle, the reticulation of threads into usefulness, the repeated turnings that echo the rhythms of all creation. She does not dwell in storehouses of either straw or gold, a prisoner of promises. No demon troubles either her nights or her days. The baby resting in the cradle is not a princess, but a precious spirit of magic and joy, held in an invisible welcoming web of simple love. She is the daughter of a weaver, a healer, a woman skilled with both hands and heart. She has grown into her own intersection of warp and weft, following the stitches of a tapestry that began long ago and continues both forward and backward, inside and out, upside and down, holding hands with itself and softly singing. hushabye, don’t cry-- all the pretty horses fly shining starborne dreams Kerfe Roig A resident of New York City, Kerfe Roig enjoys transforming words and images into something new. Follow her explorations on her blogs, https://methodtwomadness.wordpress.com/ (which she does with her friend Nina), and https://kblog.blog/, and see more of her work on her website http://kerferoig.com/ ** Maria Martinetti Speaks I see you sitting in the stone passageway, wearing a folded white mantilla, your brown linen skirt brushing the floor, and a wide blue apron across your lap to catch loose fibers. How many times will I place, erase, reposition that basket of flax beside you? See how dabs of oil dry as I create and revise? I beseech you to linger while your babe is quiet. Your spinning. My painting. I’ll make the basket and skirt match. One is rough as bark while the other slides your legs like iris petals. The woven twigs form a rough circle and are filled with dried garden gold. Shouldn’t your infant be inside the blue door napping? But the air is damp inside and we both know these breezes that roll over cobbled stones could never be more pleasant. Momentary satisfactions become such sedative that I don’t care where I paint if my subject is patient. Soon I will leave. There is noise inside the half open door. Outside, a slight cacophony of carts joins the inner metronome. Your rhythm spins linen in long threads that someone in the village will color with cochineal and sunrise while you nurse and nurture. You enjoy wearing the red blouse. Watch my deft strokes thicken sleeves that end in lace. I can never decipher who indentures me unless it is my hand. I wish I could afford sable brushes more often. How often do our doppelgangers project us on cobblestone shadows both to paint and to be painted? Mary Ellen Talley Mary Ellen Talley’s poems have recently been published in Raven Chronicles, Banshee, What Rough Beast, The Plague Papers and The Ekphrastic Review as well as in the anthologies, Chrysanthemum and Ice Cream Poems. Her poems have received two Pushcart nominations and her chapbook, “Postcards from the Lilac City” was published by Finishing Line Press in 2020. ** Her World Awakens Her milk is letting down. A droplet marks the linen she wears, a thin thread, wet white brushed with blue-- an embroidery of milk. Her world awakens taut with tension, spinning and unspooling between calloused fingers-- a warp & weave of mother & child. Nancy Gott Nancy Gott studied creative writing at the University of Iowa, in Iowa City, IA, and has a BA in English. Currently, she resides in Las Vegas, NV, and has written for several local magazines as a freelance writer. Her poetry has been published by Qarrtsiluni.com. ** How Can I Spin This? (from Son, Moon, and Talia, Giambattista Basile, 1634) The papers are comparing me to Cosby. As if I were the one to slip the splinter beneath her nail. As if I planned it. She was asleep when I found her. I thought she must be dead. What would be the harm? Who would ever know? Now she says she loves me. And you can tell just by looking, the little ones are mine. How did they survive? How will I? My god, my reputation. Rumor has it there’s an old woman in the hills who still grows flax. The last since the embargo. Can a broken curse be mended? Jacob Waddell Jacob Waddell is from Central Illinois. He has previously appeared in The Eyeflash Poetry Journal. ** Authenticity Proving Life Time She enlarges the photo on the screen then zooms in around the nose. There’s definitely something wrong with the woman. A certain shadow around the lashes, a wide-eyed prettiness she doesn’t think is right. ‘It’s a fake, Roberto,’ she declares. She sounds more certain than she feels, but with Roberto it’s always best to be wrong first and unsure second. She can always adjust her opinion at a later date. Or, if she’s feeling particularly mean-spirited, she can just pretend they never spoke. ‘Are you sure?’ he asks. ‘It says it comes with a lifetime written guarantee.’ She scrolls to the bottom of the listing. WeSellCollectibles will Issue A certificate Of Authenticity proving Life Time Written Guarantee. The random capitalization doesn’t inspire confidence, but she doesn’t say so in case he hasn’t noticed. ‘Which one of us was the art history major, Roberto?’ she asks. The answer is actually neither of them. She only took one course as an elective when she was at uni. When Roberto moved in, she saw him hanging an Arthur Streeton print and thought she’d make a good impression by flexing her artistic intellectuality. She hadn’t counted on him only remembering her art knowledge and nothing else. ‘Fine, fine.’ He closes the laptop. ‘I suppose I have to take those damn pills now.’ She helps him unclip the plastic box of medication then fills a mug with water from the sink in the kitchenette. He takes the mug but just frowns at the box. ‘Come on, I held up my end of the bargain,’ she prompts. His nose twitches and he presses his lips together, as if he’s stopping himself from saying something rude. She’s never heard Roberto swear. She’s sort of looking forward to it. ‘I don’t know what day it is,’ he mumbles. She smiles. ‘No worries, Roberto. I forget half the time too. It’s Monday.’ He nods and with a crooked finger he scoops one bicoloured pill at a time from the Monday section in the transparent box. His swollen knuckles and long, yellow fingernails fight against him, and she makes a mental note to book him a manicure. ‘If that’s all?’ she asks. ‘Yes, yes. I won’t keep you.’ He dismisses her with a wave but she hesitates by the door. From the way he’s glancing at the laptop, she’s pretty sure by dinner his bank account will be a few thousand dollars poorer. ** ‘If that’s all?’ Jeremy asks. He taps the side of his iPad to turn the screen off, signifying the end of the meeting. The staff all murmur at once, and it’s not clear if they’re protesting or agreeing. Jeremy’s managing style is, if nothing else, optimistic, so he just assumes agreement and leaves the room with a nod. She catches up to him, knowing he’s about to leave to collect his daughter from school. She doesn’t begrudge him his parental duties, but nearly all the staff have children who are about to be picked up by grandparents or neighbours. They’ll be lucky to see them before breakfast. ‘Jeremy, if I could have a word about Roberto.’ He doesn’t stop. ‘Who?’ She skips a few steps to keep up. ‘Room 345.’ ‘Ah. Yes. Problem?’ ‘Well, sort of. His family has insisted he maintains his independence here. But with the laptop and internet access, I’m afraid he’s being taken advantage of.’ Jeremy stops. ‘By the staff?’ ‘No, nothing like that. But he’s got access to all his credit cards and I think he might be buying things.’ ‘Contraband?’ ‘What? No. Art. I think he might be buying imitation art.’ ‘Ah!’ He spins back to the front doors. ‘Some posters will cheer the place up, don’t you think?’ He strides away. ‘If that’s all?’ He’s already left the building. ** She knocks and enters. ‘You again,’ Roberto says. It’s a sleight of hand, but her heart gives a little skip anyway. It’ll take him a while to remember she’s the art history major. He never seems to remember she’s a carer. He’s staring at something behind her, near the door, and she turns to find herself face to face with the painting she’d recommended he not get. ‘Recognize it?’ he asks. The way his mouth twitches into a smile makes her hopeful he’s remembered her. ‘I bet you don’t.’ Her hope slinks away. ‘How much do you bet?’ she asks as she fills his mug with water. ‘Lady’s choice. You state the wager.’ ‘How about this. If I can guess the name correctly, you have to take these pills.’ She rattles the plastic box as she passes him the mug. ‘And if I can’t, I have to take them.’ He chuckles as if he’s already won. ‘Alright. You have a deal. What’s the name of the painting?’ ‘Spinning Flax by Maria Martinetti.’ His mouth hangs open for a moment before it spreads into a wide grin. ‘You cheeky bugger, you’re the art history major.’ He shakes his head as he continues to laugh, happy to take his medicine. ‘You had me fooled there for a minute, dressed up as a nurse.’ She winks then walks over to the painting as he picks the pills from the box. It looks different than it had done on the website. The woman looks stern but focussed, at peace in her task, and it’s easier to make out the open door behind her. It gives the impression she’s just stepped out to enjoy the sunshine in the courtyard, a stolen, golden moment with her child. Roberto clips the lid on the box of pills. She shuffles to the Streeton landscape. She’s never looked at the print closely before and when she touches the glass she feels only distinct brushstrokes in oil. ‘Huh.’ ‘What do you think?’ Roberto asks, hiding a smile behind his mug. She caresses the signature in the bottom corner. ‘I think you got your money’s worth.’ Kinneson Lalor Kinneson Lalor likes writing, walking, gardening, and her dog. She followed a PhD in Physics from the University of Cambridge with an MSt in Creative Writing from the same institution while writing her first novel, teaching mathematics, and co-founding a supercomputing start-up. She is Australian but has lived in the UK for over a decade. Her work has appeared in The Mays, Tiny Molecules, and elsewhere, and she writes a regular blog about sustainable gardening for edibles and wildlife. ** Devotion I’m proud Japan supports the Allies’ fight as war in Europe staggers on in slaughter. I find some peace in painting my young daughter. Her apple cheeks here glow in late-day light; she’s a beacon, shining through the murk of olive green. I bless her with a red- orange arch like a temple overhead. I place her hand (as in Dürer’s work that I admire) pointing toward her heart. My Reiko holds a tiny, bright pink string of Lady’s Thumb as if a sacred thing– a common weed, but still a work of art. It’s art to deify, not Buddha or Christ, but all young lives the war has sacrificed. Barbara Lydecker Crane Barbara Lydecker Crane, a finalist for the 2017 and the 2019 Rattle Poetry Prize, has won awards from the Maria Faust Sonnet Contest, the Helen Schaible Sonnet Contest, and others. She has published three chapbooks: Zero Gravitas (White Violet Press, 2012), Alphabetricks (Daffydowndilly Press, 2013), and BackWords Logic (Local Gems Press, 2017). Her poems have appeared in The Ekphrastic Review, First Things, Light, Lighten-Up-Online, Measure, Rattle, Think, Writer’s Almanac, and several anthologies. She is also an artist. Three Ghosts One. She is a dirty smock, two legs planted into feet and toes I cannot clearly see. Wet collodion positive: she is glass plate inverted with the back face blackened. She is the daughter of a son, half the height of everybody else, she is a head of hair of clear on ground, dark from varnish and sandy from the sun. She is sight without eyes. She is quizzical. Her family is waiting for you to make the picture. Silver salts bloom in the darkness behind your aperture, down the barrel and plate-holder, even in the dusk of the crypta. Her face is indistinct. She turned during the exposure. Two. She is the mother of a daughter, alive, unseen. Perhaps she stepped to the side in mid-exposure. Or rather: she is a slip of your lens cover, your hat, for she does not seem to move. Stands instead, in the shadow, enclosed by rock, her skirt and earth-light the same in the black and the white of the picture. Her face in aggregate through the moonlike yellow tuff, the ancient stuff, the tufo, rising from the burning fields as lava and tephra and gas, settling onto the land so that it becomes the land. When you prepared your plate, you could not have known that the lunar caustic would bury her and make her eternal. Three. She is the lone light behind them and she is her town, Fuorigrotta, crossing under from out into Naples. Vanishing point on the remaining horizon, down the descending, telescoping tunnel. Her people have done this since the old passage was dug-- Wedges driven into rock faults, comes away in layers, and long after you (not Virgil, in one night, but the slaves under the Augustan, Cocceius) are gone the lines of their fracture still trace horizontal scars as she descends (different servitude) towards the city. Shou Jie Eng This first appeared at Singapore Unbound. Shou Jie Eng is an architectural designer, researcher, and writer, whose work examines the relationships between spaces, bodies, and the material histories and cultures of craft. He runs Left Field Projects, a studio practice located in Hartford, CT. His writing has been published or is forthcoming in Speculative Nonfiction, Ritual and Capital, CARTHA, and Paprika!, and his visual work has been shown at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, WY. The Drowning Dog Though his wife, Lori, had died some seven months before, Jeffrey Rosen still spoke with her regularly. In hospice, during the last weeks of her life, he would sit by her bed while she slept and speak to her aloud, for he felt certain that she could hear him. The closer she drew to the end, the more she slept, and the more voluble he became. Less confident after her death that she still heard him, he kept up the conversation anyway, silently in public, sometimes still audibly when alone at home in the modest gray-shingled Cape Cod house in Takoma Park, Maryland, in which they had lived together for more than thirty years. Most often, he talked to her at night and when drunk, and because his sleep had grown fitful when it came at all, and he drank more than ever, those conversations had become quite frequent of late. He sat now on his living room sofa, a squared-off, dark-blue, mid-century modern piece that he and Lori had purchased early in their marriage. A near-empty bottle of Chianti and a half-full wine glass stood on the coffee table in front of him. On the wall opposite the sofa hung a reproduction of Goya’s The Drowning Dog that Lori had bought from the gift shop at The Prado. He and Lori had quarreled over the print of the little black dog, depicted in profile, sinking—already neck-deep—into a vast ochre void. The dog’s expression, one of fear, bewilderment, and hopelessness—“Why this? Why now? Why does no one hear me?”—unnerved him. “The more I drink, the harder it is for me to get drunk,” said Jeffrey, his eyes fixed upon the drowning dog as if he were addressing it. “So I have to drink more every night.” “I hate to see you this way,” he imagined Lori answering. “I hate to see myself this way. But I have an excuse tonight. I have to fortify myself for visiting Mom. I’m driving up to New York again this weekend. She’s not doing well.” The image came to him unbidden, as it had countless times before, of his mother alone in the den of a house that in the two months since she had become a widow, must have come to seem to her as vast and empty as an airport hangar. Feeling light-headed, she would have set her knitting down upon the table. Maybe she would have lost that second or two during which she fell and then have wondered how she came to be lying prone on the carpet. Unable to rise, the entire right side of her body having suddenly gone inert, she would, like the drowning dog, have sensed that something catastrophic that she did not as yet understand was happening to her. “Again you’re going? What about that brother of yours? He’s in Manhattan, an hour away from her.” “Rob’s still doing his part. He visits her once or twice a year, whether he needs to or not.” “It’s so unfair.” “If life were fair, you would still be here.” He drained his glass and then refilled it, pouring into it all that remained in the bottle. “And that poor little dog wouldn’t be drowning. God, I’ve always hated that painting. One of these days, I’m going to take it down and put it in the basement.” “You can do as you like with it. You don’t have to please me anymore.” Finishing the Chianti, Jeffrey put the glass down on the table and lay down upon the sofa. “Poor dog. Do you ever have… any regrets?” “Regrets? About what?” “I don’t know. Not having kids? It would have been nice, maybe. When I picture growing old now, it seems so desolate.” “I would have liked very much to have a family.” “True. You wanted one much more than I did. I’m sorry.” “There’s no reason to be sorry.” “I hope you don’t. Have regrets, I mean. I know I wasn’t the easiest person to live with. It was good, though, mostly, wasn’t it? O.K., at least?” “If you have to ask now, I wonder whether you ever knew me at all. Was I the sort of person who would have stayed married for thirty-one years to a man I didn’t respect and love dearly?” How would she have posed that question? Irritably? Tearfully? The uncertainty made him fearful. He realized then that he was weeping, and he furtively wiped his eyes, as though wishing to conceal his tears from her. Would there soon come a day when he would no longer hear her at all? He saw her fading, pulling away. “No.” “So now that you have your answer, you can let me go. I’m dead. I have no existence outside your imaginings. Stop wasting your breath talking to a shadow you’ve conjured up to keep you company at night. You have responsibilities. There are living people who need you. Your mother, for one.” “You’re right, of course, but…” “No buts. Of course I’m right. I always was.” “Not always, boss. But more often than not.” “Goodbye.” “Good night. I love you.” “Goodbye. I’m dead. The dead can’t love you back.” “They speak very bluntly, the dead. As ever.” He glanced over again at the drowning dog, forever sinking into oblivion in mute despair. Yes, he resolved, as he closed his eyes, he would consign the dog to the basement. Tomorrow. He felt much too tired to bother now—so tired that he dared hope he might get some sleep. Edward Belfar Edward Belfar is the author of a collection of short stories called Wanderers, published by Stephen F. Austin State University Press in 2012. His work has also appeared in numerous literary journals, including Shenandoah, The Baltimore Review, Potpourri, Confrontation, Natural Bridge, and Tampa Review. He lives in Maryland with his wife and works as a writer and editor. A Chat with My Daughter About a Woman and Her Vase influenced by a viewing of R.C. Gorman’s Salina The way the ground and sky are painted caramel colours during dusk, and the way Salina wears white like vanilla ice cream, her hair a chocolate fudge spill dripping down her back, reminds me of cravings boys will have when they encounter females in that space between childhood and womanhood, shown here as pottery fresh out of the kiln, newly painted with groups of claw-like swirls groping this vase, and Salina appears as a desert dessert waiting outside of her bowl. See how, with chin raised, she proudly protects her virgin vase? She waits for a love to warm her skin like the sun’s fingers, waits for her heart to fully flower. ** Mountain Lessons after R.C. Gorman's Earth Mother, serigraph on paper Earth, dusted with flaky desert skin, grips this new mother covered with skin like sunsets. Earth offers her windy voice and cacti warnings as abrasive as burned crop fields, an eight-hundred-mile walk to Bosque Redondo, heartbreak. The cacti cast shadows that loom, and under the moon, this new mother whispers, don’t linger too long in their shadows. Earth hears her lessons passed on, and her cheeks warm the air with sun. The new mother is a small hill hunched in woven yarn sitting on Earth’s lap, protected by her purple mountainous shoulders, and the fringe on this new mother’s shawl matches Earth’s thirsty brown grass. ** Circles after R.C. Gorman’s Two Women, Oil on Canvas, 1981 Their white round circle hips, bellies with babies, and full breasts fused by words falling off their lips discuss what lies beyond their grip: soft lines blending triumphs and tests, and their white round circle hips attend to codes that cannot rip oil-covered canvas thinned by sweat, fused by words falling off their lips on terracotta faces that will not chip, holding onto burdens without regret, and their white round circle hips sit with equal parts praise and quip, uniting women they have not met, fused by words falling off their lips, full breasts, and laps with babies’ sips, comforted from all of the world’s threats because ladies with white round circle hips are fused by words falling off their lips. ** Ruins after R.C. Gorman’s Ruins, Lithograph, 1983 “I always was in awe of the ruins. I felt there were still people living in them, and I still feel that way.” R.C. Gorman She bends over shattered history, broken remains scattered to trail lead her backward in time, and the foreground sand moves from dark to light, offers its own answers, illuminates an empty ghost cave behind her. For how many centuries did the sun chew its way through those two phantom walls we know existed, held within its confines an entire people who needed windows, like you and me, to look out and see God breaketh not all men’s hearts alike. ** If This Chair Could Talk after photograph by R.C. Gorman, 1980 “This is Aunt Mary’s chair, which doesn’t look like a throne, but it is. She’s a queen.” –R.C. Gorman At the epicenter of settled dust, her chair sits fading and cracking under sunray pressure like a field labourer’s sad face. If it could talk, we would hear stories spanning thirty years or more about her holding lap after lapful of babies, shucked corn, potatoes. It would mention what is not in this black and white photo, beyond the chicken resting in its shade, footprints in this dirt, the chipped window paint. It would tell us the chair’s busted-out seams trap Aunt Mary’s laugh, and they (the chicken and chair) wait patiently for her return. “I’m worn out,” the chair might say, but sunlight hits one of its stainless-steel legs and begs to differ as it glistens. Brenda Nicholas Brenda Nicholas is an Associate Professor of English at Temple College. Her work has appeared in The Painted Bride Quarterly, Main Channel Voices, Red River Review, Illya’s Honey, Menacing Hedge, Snapdragon, The Helix Magazine, and other literary journals. The Ewes Must Still be Fed Warm fireside is what he wants, but he is out in snow under a setting sun night gathers at the horizon the ewes must have their hay. He is out in snow under a setting sun his back is sore and fingers numb the ewes must have their hay before he can go home to rest. His back is sore and fingers numb there’s no heat from the pale sun before he can go home to rest he still has this work to do. There’s no heat from the pale sun its light fingers grope through trees warm fireside is what he wants, but he’s in the cold, with hay for hungry sheep. Marius Grose Marius studied fine art at Bristol Polytechnic graduating in 1981 with a BA Hons degree in sculpture. He then made a career shift into broadcast television, becoming a freelance editor. Marius has worked on factual and entertainment shows, documentaries and feature films. Always interested in writing and story telling Marius has written screenplays for film and television. Since 2016 has been writing poetry and reading his work at open mic nights. He has had poems published in the literary arts journal Dream Catcher and in the ezine 192. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|