|

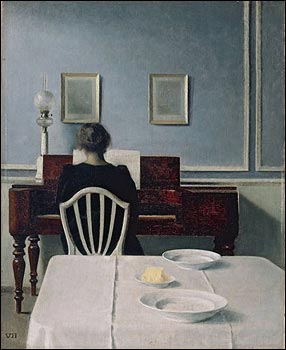

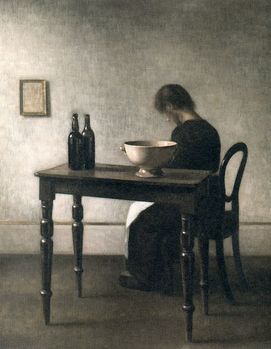

Fifty Shades of Grey: the Evocative Silence of Vilhelm Hammershoi

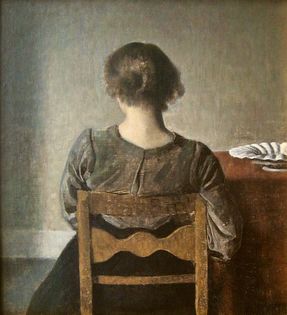

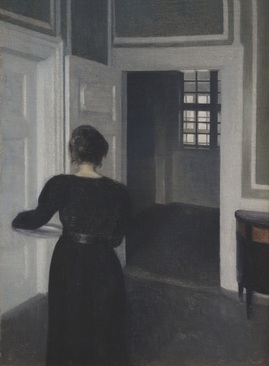

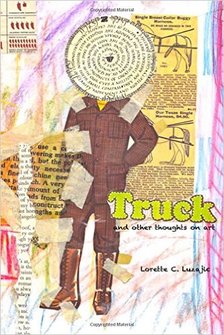

Vilhelm Hammershoi’s curiously withdrawn paintings of muted, spare interiors and a faceless woman in black are most often compared to Jan Vermeer and Edward Hopper. I see the chain of continuity, but Vilhelm’s works also contain an understated current of erotic poetry. There is softness in the hard angles, and a sense of eavesdropping, of happening on a window and looking into someone’s private world. These are not mere depictions of blank walls and pianos and housewives reading letters. They are haunted, too. The grey Dane was a reclusive, elusive man whose art garnered modest recognition in his lifetime. But after his death to cancer, just shy of a century ago, he faded into relative obscurity. There was an important retrospective at the Musee D’Orsay in 1998, and a well-received exhibition at the Met in 2001. Yet Hammershoi remains a cult figure. He is revered by a ragtag assortment of followers intrigued by the unsettling beauty of his images. The works fetch sizeable sums from museums at auction. But, perhaps as he would have wished, he has never found the limelight. By the few accounts we have, we understand Hammershoi was a reticent man, preferring solitude or quiet company. He was described as “taciturn” and shy. He spoke softly, and was painfully sensitive. He had his own kind of closeness with a chosen few, especially his wife Ida, subject of most of his portraits. His paintings reflected the quietude he sought. “Hammershoi’s ‘reality’ is a room devoid of people,” wrote Dr. Kasper Monrad, chief curator at the National Gallery of Denmark. The artist’s legacy was bolstered by a chance encounter with Monty Python’s Michael Palin, who found himself enchanted by the uncluttered, desaturated interiors and the mysterious figure whose back is always turned. Palin said the artist’s grey and sepia paintings stood out from others, “like undertakers at a carnival. These…sparsely furnished rooms, almost stripped of colour, conveying a powerful sense of stillness and silence…there was something about the work that drew me like a magnet. Something beyond appreciation of technique or decorative effect, something deeper and more compulsive, taking me in a direction I'd never been before.” Palin followed his muse to Copenhagen and made a documentary film, thereby dusting off the bygone relic and reviving Vilhelm to a brief vogue. Besides Jan Vermeer and Hopper, there is little to compare to Hammershoi’s work. Alex Colville and Hopper share something of their detachment. They too convey ordinary life scenes with a kind of eeriness that is difficult to pin down. Magritte sometimes used a similar labyrinth of doors and windows to create mystery. And the tonalist artists of Hammershoi’s time certainly influenced his palette with their ranging greys. We know he liked Whistler, for example, because he painted his own version of Arrangement in Grey and Black (Whistler’s Mother). Vermeer’s influence is obvious in Vilhelm’s interior subjects, light, and perspective. Indeed, after the 1998 retrospective, he was dubbed, “the Danish Vermeer.” But Hammershoi distinguished himself from both his teachers and his heirs by stripping colour and detail utterly from his scenes. With all distractions gutted from the narrative, we find in the starkness a stunning, subtle subtext of sensuality. What has been removed, what goes unsaid, what lies beneath, is the real story in these paintings. The shifting light through the window, the people frozen in time. How we are standing at the edge of the painting, looking in, like the artist himself. Hammershoi’s rooms are pared down, and his subjects are oddly unadorned, placing them in a kind of still-life twilight zone. But their quality of isolation does not beg for change. The paintings are evocative vignettes, haikus of sorts to the beauty of the ordinary. One gets the sense that much more would shatter this fragile shelter. He is already overwhelmed. “Each of them looks like the sad home of a recently bereaved widower, whose place has been forcibly tidied up by a cold, hard, bureaucratic, social worker,” writes Christie Davies, who does not see what I see. She chides the artist for having “locked himself into his glum apartment in Copenhagen with his dull…wife and produced dull, glum interiors which he sold to his dentist.” But I think that Vilhelm understands that he has all he needs, even if he seldom leaves his house. Christie minces no words in expressing her repugnance towards the “bleak houses” and bare walls and the “total absence of cheerful, welcoming clutter.” But I find each quiet conundrum to be like the moment of a sharp intake of breath. In their very stillness one can hear the heart beating wildly. Christie finds the Danes’ unusual claim to fame as top producers of hard-core pornography unsurprising in light of such art history. “Perhaps it is necessary to arouse them from their dreadful ennui…Better they add lithium, for their souls are eaten away by spiritual caries…We can see from Hammershoi's work that the Danish sky is an endless undifferentiated grey and there are no hills.” Perhaps. Vilhelm and his wife really did live in the kind of minimalism he portrays, with walls and furniture they painted white themselves. We are painfully intimate to the artist’s awkward reservation. There is the sense of existing apart from the routine clatter and upheaval of life. Indeed, This indicates to me someone who was extremely sensitive and easily overwhelmed. Many said the painter had neurasthenia. This was a popular but vague diagnosis in his time, pointing to a variety of nervous conditions from dyspepsia to chronic fatigue to depression. But I feel there is an attentiveness to beauty, even if it is redefined by minimalism. There is a sense of awe rather than alienation. There is a reverence towards mystery. It’s as if Hammershoi found solace, and soul, in his unique relationship to the world and to Ida. To some degree, he understood or made peace with his own limitations, and he accepted those of his wife. Maybe Vilhelm did not require bright colours and rolling hills for a deeply sensual experience of life. In my study of art, I return time and time again to the writings of Thomas Moore. Moore writes more about music, psychology, God, and even golf than he writes about art, but as an especially gifted observer, he shows me how to see. A recurring theme throughout his work is that real depth of experience comes from entering fully into life’s mysteries, including the painful ones. Instead of viewing every uncertainty, imperfection, quirk, or heartbreak as a pathology that needs to be tidied up and fixed, we can open ourselves to what it reveals about our soul. It’s not that we should never strive for better; rather, Moore acknowledges that both the hands we are dealt and the choices we make lead us into a range of encounters that deepen our very humanity. My sexy has been filled with tumultuous highs and nightmare fall outs, and looks nothing like the serene and vacant world of the Hammershois. Its excesses and lackings have been messy and fraught with dramatics, inconsistent and embarrassing. “Colourful” is a fitting, if polite, description. In contrast, what we can see of Hammershoi’s is reserved, restrained, almost elegant, in fifty shades of grey. So very, very naked. Art allows us to conjure the lives of others. The fact of fiction gives us access to other realities. In speculating on the private world that Hammershoi has revealed publicly through his art, I can’t help but thinking about Moore’s insights on love and sexuality in his books Soul Mates and The Soul of Sex. The paradox of finding such intense sensuality in the chaste, introverted renderings of this painter makes sense through Moore’s lense. That Vilhelm paints interiors with such sensuousness is even more interesting in light of Moore’s observation that, “The word ‘intimacy’ means ‘profoundly interior.’ It comes from the superlative form of the Latin word ‘inter,’ meaning ‘within.’ It could be translated… ‘most within.’ In our intimate relationships, the ‘most within’ dimensions of ourselves and the other are engaged.’ There is a heartbreaking dispassion in Vilhelm’s artworks, rendered in the almost obsessive neutrality of his depictions. Yet the artist remains focused on his wife, allowing all of us to share his preoccupation. His idea of beauty is unadorned, to be certain, but there’s a sense of complete surrender to the terms of the relationship. There’s a tenderness sometimes absent in more raucous, racy, noisy ways of desire. There is an exquisite intimacy within the seeming aloofness. Look at the rapt attention he pays to the naked curve of her slender neck. The few mussed tendrils against the bare skin are almost a fixation. Ida is a geisha. The nape, which the Japanese once saw as a woman’s most erotic aspect, is vulnerable and exposed. Whatever the dynamics of their marriage, there is an understanding between them. There is no tension in the air, and the melancholy is balanced by some kind of reverence. “It isn’t easy to expose your soul to another, to risk such vulnerability, hoping that the other person will be able to tolerate your own irrationality,” Moore continues. “It may also be difficult…to be receptive as another reveals her soul to you. “ Such mutual vulnerability is “one of the great gifts of love.” The gaze of the artist is almost fetishistic, and once you notice it, all the pretenses in the paintings and in your mind begin to unravel. You have a hundred questions. Is the woman waiting in vain to be touched by a man who is too tentative or tepid? Is she playing a losing game of temptation with a husband who is really married to his nervous disorders, or to his paintings? Was this as far as he could go, in his imagination? Or, is this all that she will show him? Is this what she has had to become, for him? The couple had no children. Is the barrenness of these pictures a more literal key? These tantalizing scenarios toy with my inner voyeur, but I keep coming back to the lack of desperation in their distance. There is a comfortable certainty between them. Was the artist so reclusive that he found it safer just to look? Or was Ida the one who was aloof? That she never returns his gaze seems a reasonable clue. Perhaps he cannot bear for her to return his gaze. He is safe where he is. Perhaps she can only bear to be seen, not touched. There is no sex in these paintings, and yet, I feel, that sex is part of their subject. It’s there right away, in our uneasiness when we first find ourselves inside of them. Sex is many things, gorgeous, topsy-turvy, sacred, complicated, ugly, absent. Sex is a shape shifter. Whenever we thing we’ve got the hang of it, figured it all out, come to terms with whatever it is we need to address or accept or change, it reinvents itself and takes us for another sort of ride. We may find our ravenous curiousity about who is doing what to whom shameful and pathetic, but it’s rooted in more than lasciviousness. We are constantly trying to place ourselves and our shoulds and woulds and wouldn’ts on the human spectrum, and it’s a never-ending puzzle because where we find ourselves keeps changing. Every relationship and every unrequited desire changes the dynamic, exposing more of our interior world to ourselves and to others. Sexuality is the theatre in which our most intense fears and weaknesses and our most painful wounds show themselves. Whatever our particular darkness, it rears its ugly head in our sexual dramas. It is where we enact our unresolved rage, losses, regrets, and betrayals. In it, our obsessions and compulsions are manifest. Conversely, it is also where our highest traits are brought to light. It is where we overcome our selfishness and heal deep-seated hurts. It is where we practice generosity, love, fearlessness, courage, openness, commitment, nurture, or self-control. Hammershoi’s paintings are erotic hauntings. More frank treatments of sexuality, or vulgar ones, are in no short supply, and there are pragmatic perspectives and funny, bawdy ones, too. There are spellbinding explicit paeans to desire. But Vilhelm’s paintings remind us that sex is hidden. No matter how many times we have it, or don’t have it, analyze it, moralize it, medicalize it, avoid it, or confront it, there is still more mystery to fathom. In the deepest recesses of our psyches and our bodies is this mystery, the literal meaning of life, which we can never wholly grasp or catch up to. It is obscured even if we are addressing it directly, or doing it, for that matter. We return to it, over and over. We have all of us evolved various defenses and compulsions in response to the heaven and hell or Eros. Vilhelm’s paintings of empty rooms and his evocative portrayals of his most intimate relationship reveal some of his. They are open-ended questions, with a silence that is all at once patient, reverent, despondent, and poetic. He is on the outside looking in, while she is on the inside, looking away. Lorette C. Luzajic Lorette C. Luzajic is the editor of Ekphrastic, an artist, and the author of over fifteen books, including the poetry volumes, Solace, and The Astronaut's Wife. This piece originally appeared in her current book, Truck, and Other Thoughts on Art.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|