|

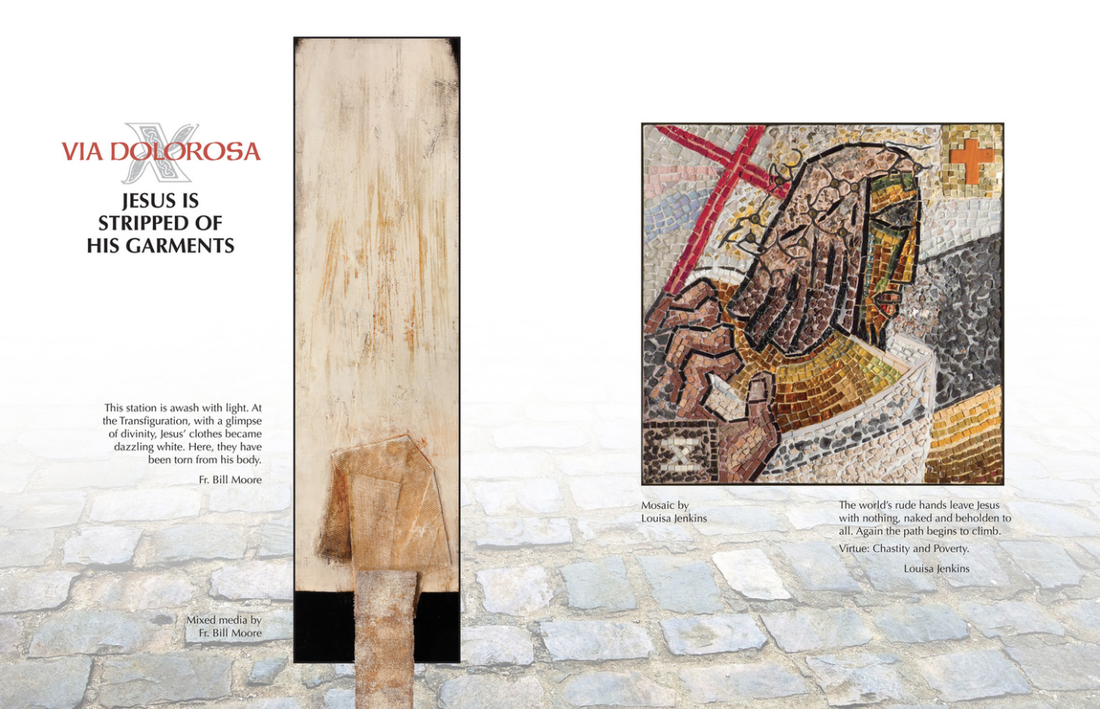

14 Stations, Portrayed by Fr. Bill Moore and Louisa Jenkins Sasse Museum of Art, 2020 (37 pp) https://view.publitas.com/inland-empire-museum-of-art/14-stations/page/1 14 Stations – An Experience of Despair and Faith I sit alone in a room on this Friday night before Palm Sunday as the COVID-19 virus roars through the world. At times it feels as if this bleak distancing will go on indefinitely for all of us. And on top of social deprivation there is the sense of a slow but steady flattening of my senses. The effects are disorienting. Disturbing. I open an eBook, 14 Stations, published by the Sasse Museum of Art, moving past the introductory pages and am immediately struck by the intensity of the art—paintings by Fr. Bill Moore and mosaics by Louisa Jenkins, vivid and luminous, rich in colour and depth. Almost a sensory overload. - Journal entry, April 3, 2020 In the face of these challenging times, what would a book like 14 Stations, focusing on a very Catholic subject, have to offer a non-Catholic, a non-Christian, or even an atheist? What would this book, recommended by a friend, have to offer me, an occasionally struggling Episcopalian? How could a book like this show any of us a path away from isolation, darkness, and despair toward hope, faith, and meaning? As a remedy for the dulling weight of social and psychological distancing, this book was and is stunning, confronting us with interpreted scenes from the last day of Christ on earth, his suffering and death, in all their horrific immediacy. Stations of the Cross, a series of devotions commemorating this last day, began as a practice of medieval pilgrims unable to make the journey to Jerusalem, to “follow” the Via Dolorosa, the actual path followed by Jesus on the day of his crucifixion. The devotions focus on 14 moments, beginning with Christ’s condemnation and ending with his being laid in the tomb. The art of 14 Stations, which is the heart of the book, is arranged in couplets—Fr. Bill Moore’s abstract paintings (mixed media on canvas) on each left-hand page and Louisa Jenkins’ mosaics on each right-hand page. This positioning, where painting and mosaic appear to speak to each other, allows us to become a part of the art’s conversation, intimately sensing through seeing, the despair that must have accompanied Jesus on his final earthly walk. Each couplet of art represents a Station of the Cross. Each artist has accompanied his/her individual pieces of art with comments. Louisa Jenkins’ comments on her mosaics are short, composed and careful. They focus on details. Fr. Bill’s comments on his paintings, equally brief, are breathlessly impressionistic and suggestive. In many ways, the style of each artist’s comments is reflective of their art. In the service of the Stations, the participants move from one image to the next, each of the 14 images laying out the stark circumstances of the moment. At each image prayers are recited, and one meditates on the meaning of each of these moments on the day of Christ’s death. The book’s design and layout, created by Fred Hartson, allow us this same journey. As we move along in the book, we see the path of stones laid out along the bottom of the pages, and we walk the Via Dolorosa ourselves. We feel the hardness of the grueling path of Christ on the day he died. We sense the fear and cruelty which led to those awful moments. And our own challenges, our own feelings of loss, aloneness, and uncertainty, become small. On the surface, there seems to be a separation between the two artists’ works: Louisa Jenkins’ mosaics are stable and set in place. Created in 1951, and composed of a rich variety of textures and materials, including many in tones of gold, they are now located in a Benedictine community of faith at Mount Angel Abbey in Oregon. Each mosaic echoes the stylized, iconographic tradition of Byzantine mosaics in stark and stiff abstraction. Fr. Bill Moore’s paintings, created more than fifty years later than the mosaics, are richly and deeply fluid in their expressiveness. They seem vibrant and alive, moving almost musically on the canvas and yet calling up a stillness in the viewer. They often include “found objects” placed quietly in the work. Their abstractness allows the viewer to enter into the paintings and find an individual meaning. Both artists see a singular and significant reality in the events memorialized by the Stations of the Cross, and both aim to strike at the heart of that deeper reality by abstracting it. They seek to touch a truth that can only be reached if it is not made visually obvious, if it does not conform to our usual expectations of the physical world. In 14 Stations, Jenkins’ iconography and Moore’s abstract expressionism meet on the pages to call forth the essence of a faith in redemption and salvation through sacrifice. In much the same way, the words which accompany each of the 14 Stations are suggestive of deeper truths. For the 10th Station (“Jesus is Stripped of His Garments”) Jenkins writes, almost poetically: “The world’s rude hands leave Jesus with nothing, naked and beholden to all. Again the path begins to climb.” With these words, she is pointing toward details of the mosaic, but leaving the implications of this moment to the viewer. Father Bill’s text accompanying his painting of the 10th Station states simply, his words almost a mosaic, “This station is awash with light. At the Transfiguration, with a glimpse of divinity, Jesus’ clothes became dazzling white. Here they have been torn from his body.” One of the greatest virtues of the comments which each artist attaches to his/her work, is their brevity. Like the art itself, the words do not distract. They lead the viewer/reader to more reflection—to a more profound reality revealed. This book was published at a time when we were shrouding ourselves with self-protection, isolation, and social deprivation. 14 Stations shows us moments in a much larger act of horrific sacrifice, an event that has become one of the foundations of western civilization. But the works of Jenkins and Moore also reveal an undercurrent of faith in a significant reality—that such sacrifices, such pain and loss, can lead to extraordinary transformations of the heart and soul. Louisa Jenkins’ faith in the existence of that deeper reality, beyond what is presented in the physical world, ultimately led her beyond Catholicism and mosaic-making in her later life. Her journey caused her to spend time in a Zen monastery in Japan and to shift toward scroll-making in her artistic work. She never went back to mosaic-making. Fr. Bill Moore continues his life as a priest in the order of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts. He continues to seek communion with a deeper reality through the melding of his art and the work of his order: helping the needy and abandoned in the world. For Jenkins, at the time she fashioned the mosaics, the path to a more significant reality, was found in the simplicity, symbolism and iconography of the mosaic form. In her book, The Art of Making Mosaics, she describes the artists who created the Byzantine religious mosaics: “[They] deliberately adopted these techniques to convey staggering truths which had no counterparts in nature, which could be told in no other way.” Referring to the dark path of marble chips that thread through her Stations mosaics (easily visible on pages 4 and 5 of the book), she at one time commented, “That’s the road we’re all on.” In his artist statement, Fr. Bill Moore says, “My art is all about hope in, and love for the physical world, which according to my beliefs and traditions, can link us to the spiritual realms—to God.” It is in those moments of linkage that the transformation, the communion, occurs. In a conversation with him, I learned that Fr. Bill has a deep appreciation for things of the senses: things from the earth, music, found objects. But not for their own sake. They are transformative ways to connect with "The Other", "The Divine"—he understands that others use both terms interchangeably with "God". These two artists have faith in the transcendence of art and its power to connect us to deeper realities. They fully offer that faith to us in 14 Stations. It is the kind of faith that each of us must find in order to weather today’s and tomorrow’s loss, despair and fear. It is a faith in the potential of the human spirit to express the inexpressible, to find linkage with things only the spirit can know, to uplift and enlighten. Kate Flannery Kate Flannery is a writer and practicing attorney living in Claremont, CA. Her other published works include short stories, flash fiction, poetry and literary reviews.

1 Comment

Nathan Zodrow, OSB

6/15/2020 12:32:48 am

Kate, a penetrating and reflective consideration of these important experiences. Everyone’s personal narrative has something to gain. N

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|