|

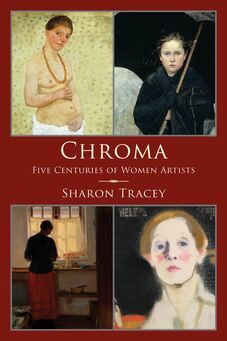

A Conversation with Sharon Tracey Author of Chroma: Five Centuries of Women Artists Shanti Arts, 2020 Paperback, $12.95 ISBN: 9781951651497 90 pages Libby Maxey: Your new book, Chroma, is entirely ekphrastic, covering (as the subtitle says) five centuries of women artists. Did you embark on this project intending to build a full-length poetry collection, or did the vision of the book take shape more gradually? Sharon Tracey: At first, the poems were just an extension of my life-long love of looking at paintings and experiencing the thrilling ways a work of art can make you feel. I probably had a dozen poems written—all inspired by the work of women artists, so often overlooked in the history of art—before I began to consider the possibility of a larger collection and possible book. At that point, I began to see myself as both poet and curator, with an opportunity to write ekphrastic poems that could also collectively highlight women artists and reference the times in which they lived and worked. Such were my initial thoughts. I can tell you, the hardest thing was setting boundaries for the project as I continued on, as the choices seemed infinite. I have many half-poems and ideas I would love to return to someday, along with a long list of women artists and paintings to inspire future poems. LM: Where does that life-long love of paintings come from? What kind of experiences with visual art—as a student or creator or museum-goer—gave you the confidence to take on the life and work of these women artists? ST: I have enjoyed making art and viewing it as long as I can remember, but here is one particularly vivid memory, when I viscerally felt that art mattered in important ways: I was living in Florence, Italy at the time and was visiting Munich when I saw an exhibition of Wassily Kandinsky’s work. I remember it was a Sunday and that the paintings glowed like stained glass, how they seemed to vibrate. This was before I was aware of his book, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, in which he discusses the psychology and language of colours, how colours embody music, emotion, spirit. It made important sense to me. Seeking out paintings became a kind of meditation, solace, and renewal. To replenish, to see what we can see, what we bring and take away, what we can save. What keeps us coming back. Museums and cathedrals are not so very far apart in some ways and are my two favorite places to visit in any city. Back then, I loved the work of artists such as Kandinsky, Matisse, and Cézanne and I didn’t stop to ask where all the women were—which now has become a sort of obsession, discovering both new and older work by women artists. LM: You’ve certainly educated me; I might never have heard of most of these women were it not for your work. I’m struck by how many of the poems in the collection are based on self-portraits; your depiction of an artist has an extra layer or two when you’re responding to how she depicts herself, which could be either helpful or intimidating. Several poems even take the form of a letter from the artist herself. What were you hoping to bring to the project with that approach? ST: I love the multiple reflections in self-portraits—the artist depicting another self and the viewer/writer responding to that depiction in various ways. So many possibilities. I had a feeling I could illuminate something, try to stand with the artist for a moment in the studio. And the farther back in time and history I traveled, the freer I felt in responding to self-portraits, leaning into the history, time, and place of a particular artist. In what I call the epistolary/persona poems—a letter in the voice of the artist to create a different kind of self-portrait—I use the subject of the painting as a jumping-off point for the poem, while imagining the inner life of the artist and referencing a biographical fact or two along the way. For example, with Rosa Bonheur’s Ploughing in the Nivernais, I wanted to convey her deep and abiding love for animals, the subject of her best-known work. Observing the oxen in her painting, I thought of Saint Luke, patron saint of artists (who is reported to have been a painter himself) and how the winged ox is his symbol, and the idea for the poem sprang from the painting in that way. I love how letters can create a sense of intimacy with the reader; combining the epistolary and persona forms was another way to create intimacy with the art and artist. LM: Were there some poems that you found especially difficult to write, yet you couldn’t let the art—or the artist—alone? ST: I had the most confidence when I had something tangible and personal to hang on to. For example, several years ago I visited Helsinki where Helene Schjerfbeck was born and painted many of her self-portraits. And as I stood at the edge of Helsinki Harbour, tasted cloudberries from the market, and smelled the spruce, it was as if I had permission to write in her voice and the poem (“Self-Portrait With Black Background”) came fairly quickly. In contrast, the more well-known an artist and painting, the more challenging it was, such as with Frida Kahlo’s Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird. So much has already been said and written (and I did find a way to incorporate the word cliché into the poem). But I couldn’t let go of a thought I had as I viewed the painting—that we women are often putting “pretty pins in our hair,” ones that hurt. And I wanted to try to work with that. LM: As you’ve indicated, many of these poems do foreground place and time, as much as they’re poems about people and their art. You’ve grouped them into “galleries,” which, like physical galleries in a museum, contain the art of an era, a defined period of years. This choice is particularly noteworthy because you start with contemporary artists and go back in time from there. Why did you choose to order the collection that way? ST: I knew from the beginning that I wanted to present the poems in a series of galleries as if the reader were physically walking through a museum. And I wanted to create what I hope to see more of in the world: exhibitions dedicated to the collective work of women artists, rather than a work here and there, often displayed in isolation amidst the work of male artists. Initially, I organized the poems/paintings chronologically, moving from the past to the present, which is often how art history is presented. But the more I thought about it, the more it seemed interesting to take the opposite approach and present the contemporary work first and then move back in time and history. I also thought that starting with more recent paintings would reinforce the idea of building upon the foundation of those who have come before. There’s another clue I hope readers/viewers will ponder: the titles of the poems/paintings (one and the same) hint at the range of subject matter afforded to women artists at different points in history. I should also note, that once a reader steps into a gallery with its specified time period, the poems are arranged “on the walls” in a way that made sense to me as curator, in terms of how they might best relate to one another. LM: A full-length poetry book is always, to some extent, a labour of love, but some poems call for more labour than others. Is there a poem in the book that nearly wrote itself, one that became what you wanted it to be without much revision? ST: From the beginning of the project, I had Amy Sherald’s Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance) in mind to include, not only because I love the painting and her work in general, but also because I love her layered and thought-provoking titles. For this particular painting I wrote an epistolary poem, or you might call it a fan letter (in fact I signed the letter that way). The poem came quickly, and I hope it conveys both the excitement and unease I felt viewing the painting, that moving spark of connection. Another example would be the concrete/found poem I shaped and collaged inspired by Box of Coloured Objects by Lucy Mackenzie, an artist who makes exquisite miniature paintings of everyday objects, giving them intense attention and time, and using such detailed brushstrokes it’s as if you could reach into the two-dimensional space and hold them. They are small still lifes but also seem larger than life in strange and wonderful ways. Upon viewing the painting, I immediately envisioned creating an imaginary box of my own that could hold a small world of her paintings (the box created visually by the placement of text). So I gathered sixteen paintings, represented by their titles, and set them down to make a found poem fairly quickly, including among them “two shuttlecocks,” “pear and fork,” and “Vermeer eyes with pearls.” It was like putting together a puzzle, in a satisfying way. LM: Many of these poems speak to the microcosmic world of a piece of art: one quotes Blake’s line, “the world in a grain of sand” (“Green and White”); in the next, the artist “gathers all of summer / in the air / and drops the days / into her humble squares” (“Summer”). That poem ends with the lines, “see what lasts, / what goes—“; what lasts for you after having put this project between book covers? ST: Yes, many speak to a microcosmic world, but the opposite is also true. The tension—between the forest and trees, so to speak—often adds something extra to a work of art. In terms of what lasts, for me, it is the idea of a permeable line between painting and poetry that you can sometimes see, hear, feel, and even cross when you bring close attention to a work of art. The way words can paint a picture in the mind, a painting can draw out language in response. A catalyst or connection that rings true in different ways, based on our own tastes, experiences, and memories. The idea that an artist’s voice, hand, and history are embedded in the work. That an artist can "drop the days" into a painting. Also what lasts is the collective power of bringing women artists together, across boundaries of time and geography, to view how they, in a sense, painted their own history at a particular point in time. What lasts for me is the desire for more—more work by women artists, more poetry, more stories, more remembering and recognition in the history of art. More windows for understanding the world and ourselves. I open Chroma with two epigraphs that, together, speak to all of this. The first is from Simonides of Ceos, the second from Sappho, to whom I’ll give the last word: “Painting is silent poetry, / and poetry is painting that speaks”; and "You may forget but / Let me tell you / this: someone in / some future time / will think of us." Libby Maxey, with Sharon Tracey Click here to view or purchase Chroma. Libby Maxey is a senior editor at Literary Mama. Her poems have appeared in Emrys, Pirene's Fountain, Stoneboat and elsewhere, and her first poetry collection, Kairos, won Finishing Line Press’s 2018 New Women’s Voices Chapbook Competition. Her nonliterary activities include singing classical repertoire, mothering two sons, and administering the Department of Classics at Amherst College.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|