|

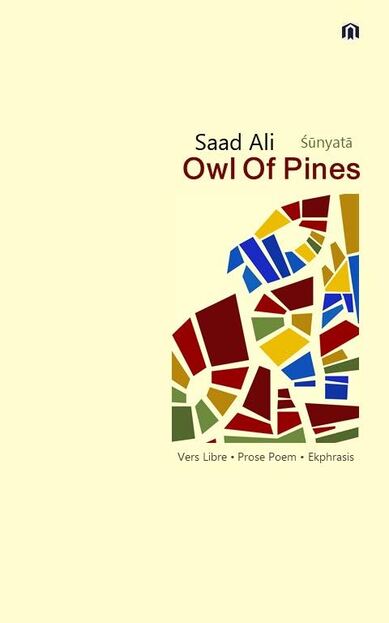

A Review of Owl Of Pines: Sunyata Saad Ali’s new book of poems, Owl Of Pines: Sunyata, is in my hands. Some of my critics have accused me of being a prolific writer of verse, a feature that leads inevitably to avoidable repetition. If speed of writing is under scrutiny, I think Ali is easily the winner. His output is torrential. But more importantly, his output continues to be of high quality; it is variegated and many-sided; and it advances poetic insights with great verve and passion. Ali has, once again, confirmed his ability to combine skill with substance that is of significance in the contemporary world. He covers an extensive range of subjects including philosophy, politics, history, literature, sciences and the arts. Questions concerning epistemology and ontology are at the core of his work. But the greatest focus is on the Human Person as a feeling, living, observing, experiencing and learning entity. A deep human compassion bubbles up from the flow of language and words in his poetry. A reader, or ‘conscious reader’, in the poet’s words in the Preface, will enjoy this book of poems, if it is read as a continuation of his earlier oeuvre. He has already authored four books of poetry: Ephemeral Echoes (2018), Metamorphoses: Poetic Discourses (2020), Ekphrases: Book One (2020), and PROSE POEMS: Βιβλίο Άλφα (2020). In these books, the poet experimented with a variety of forms, like ekphrastic poems, prose poems and free verse. This book has been divided into separate sections called ‘Kind’. These sections are devoted to Vers Libre, Prose Poem and Ekphrasis, respectively. This, then, becomes a comprehensive feast of Ali’s poetic hospitality. Ali’s prefaces are not to be read as insignificant pieces to be skipped over; they capture the spirit that informs his creative work. The following sentences found in the Preface are not merely clues, but keys for understanding as well as enjoying the poems contained in this book: (i) Well, I think ergo I wonder! … (ii) Owl happens to be my favourite animal (bird). … Perhaps, it’s my desire to be reincarnated as an owl. … Perhaps, it is also my desire to be reincarnated as a pine (tree). (iii) So, what kind of a beast (or book, if you like) is this? Put simply then, it is a Chimera … with three heads (or tails, if you like). (iv) On the subject of ‘The Theme’: … there isn’t any single theme here though. … —since I belong to the kind called homo sapiens, I cannot … ‘free’ myself from this primary contextual point-of-reference anyway. (v) ‘Sunyata’ (or emptiness) … is the space where nature and things of nature … interact and integrate … . (vi) … this is poetry and not a discourse on, and/or deconstruction of the genealogy of, human origins … (or deconstruction of the human nature). I read three important messages in the above extrapolated quotes for the reader: (i) First that poetry derives its energy from a deep sense of wonder about the universe, nature and humankind. Wonder is an antidote to materialism. This, to my mind, puts it in the league of post-modern verse. Substituting the miraculous and the divine in the religious imagination is the sense of wonder not only in the universe, nature, and humankind, but especially so in language and its deconstruction in terms of ‘deferral’ of meaning of words, and the continuity between absence and presence. For me, Ali’s poems stem from that innate sense of wonder. (ii) Secondly, the metaphor of ‘chimera’ most aptly and incisively conveys that fundamental force of wonder animating his verse. The owl-tree-poet relationship is enacted in the space, which is the scene of Sunyata, as interpreted by the poet. (iii) And finally, and very importantly, the poems are not to be read as propounding this or that philosophy or doctrine or dogma. In sum, these are philosophical poems, and not poems versifying philosophy. This is a very significant facet of the poems and clearly articulated by the poet. If there is a philosophy that he stands for unequivocally, it is the complexity, beauty and dignity of the human animal or the true ‘chimera’ of this book. Ali has a veritable treasure-house on display in this book. There is a wealth of poetic insight in eye-catching imagery, and mind-teasing thoughts. There is plenty of grist for the mills of the intellect as well as imagination. Readers can choose from vers libres, prose poems and ekphrases. Explanation in any of these sections will be rewarding. Let me refer to some of the poems that filled me with a sense of pleasure and indeed helped to broaden my imagination: (i) The poem, ‘Again! – Sunyata (II)’, has very engaging lines with brilliant images. ‘The stylo is the wild, wild stallion. The flame is dancing on the forehead of the candle-wick. … The book pages are singing. … The mouse is wiggling on the mouse-pad. … The keys are performing flamenco on the tablet.’ (ii) Light-hearted comment brings out a serious point on philosophy in ‘Philo & Sophia’: ‘What does religion and science have to do with ‘philosophy’? ... she inquired. … Isn’t religion, science, history, et cetera concerned with seeking the truth … knowledge … wisdom?’ Then, after an intervening passage on the ‘wisdom’ of paying utility bills, comes the advice: ‘So, be a GOOD PHILO and tend to THIS SOPHIA’. I must confess that the poems I savoured most in this volume fall in the category of ‘Ekphrasis’. I believe no other poet in Pakistan has more creditable poetry than his in the multi-disciplinary field of ekphrasis. Some of the poems I relished are: (i) ‘A Tale of an Ordinary Day’ (after Edward Munch’s painting Spring Day on Karl Johan Street, 1880), which reads: I need to allow the lines and words to stretch and breathe, too. … ‘I saw Europe’s fractured leg, I saw Himalaya’s broken torso, I saw India’s crippled chicken-neck, I saw Gaza’s weeping eye, I saw Amazon’s dry mouth, I saw Sahara’s limping limbs, I saw Australia’s burnt brain. (ii) And poems like ‘The Only Guy Wearing the Fedora Hat’ (after Fernand Leger’s The Man in the Blue Hat, 1937), ‘The Final Exchange’ (after Bertram Brooker’s Figures in a Landscape, 1931), ‘The Hunting Grounds Tonight: Hot Spot Café’ (after Van Gogh’s Café Terrace at Night, 1888). It is always difficult, even rash, to choose one poem from a collection and call it the best. This poet has a penchant for dedicating each and every poem to his friends or acquaintances. He has very kindly dedicated his poem ‘Kashmir’ to me. Kashmir is the Laila of one’s dreams. It is a beautiful poem recalling Kashmir’s Helen-like loveliness and Circean suffering in the same breath. Most of his poems explore the possibilities of intellect, emotion and language in his poems. But for one, who believes that the language of sentiment and emotion should be the vehicle of intellectual content, and not the reverse, poems that can be declared as ‘the best batsman of the tournament’ are those in the mould of ‘Beer and these Lines’ (after Conversation with God by a Polish painter, Jan Matejko, 1873). I love its lines: We came in too fast & too furious. And we collided head-on! It has taken my neurons three cans of beer to come to their senses; & I came up with these lines. Well, it is time to pop open the 4th one!-- What can/will happen? We will have a few exchanges —some harsh words, some sweet words-- & will be back on the track! The ‘proof of the pudding’ is the fact that this beer poem has fascinated a teetotaller like myself. And luckily for the poet, our policemen don’t care for English language verse, otherwise, this confessional could mean a little more than ‘some harsh words.’ I wish Saad Ali consistent luck and continuing success. Ejaz Rahim Ejaz Rahim was born in Abbottabad, Pakistan. He is a Senior Civil Servant (Retired). He earned his Masters Degree in Development Studies from the Institute of Social Studies, The Hague, Netherlands and MA in English Literature from the Government College, Lahore, Pakistan. He is a poet and an author of over twenty books of poetry including: I, Confucius and Other Poems (2011), That Frolicsome Mosquito Our Universe (2014), Through the Eyes of the Heart (2014), et cetera. He holds the honour ofSitara-e-Imtiaz awarded to him by the Government of Pakistan for his contributions to the English Literature and Literary Scene in the country. Currently, he resides at the foot of the Margalla Hills in the Capital, Islamabad, with his life-long partner. Saad Ali (b. 1980 C.E. in Okara, Pakistan) has been educated and brought up in the United Kingdom (UK) and Pakistan. He holds a BSc and an MSc in Management from the University of Leicester, UK. He is an (existential) philosopher, poet, and translator. Ali has authored five books of poetry. His latest collection of poetry is called Owl Of Pines: Sunyata (AuthorHouse, 2021). His work has been nominated for The Best of the Net Anthology. He is a regular contributor to The Ekphrastic Review. By profession, he is a Lecturer, Consultant, and Trainer/Mentor. Some of his influences include: Vyasa, Homer, Ovid, Attar, Rumi, Nietzsche, and Tagore. He is fond of the Persian, Chinese, and Greek cuisines. He likes learning different languages, travelling by train, and exploring cities on foot. To learn more about his work, please visit www.saadalipoetry.com, or his Facebook Author Page at www.facebook.com/owlofpines. Read an interview with TER and Saad about this collection, here.

2 Comments

3/7/2023 01:48:51 pm

Congratulations, Saad Ali, on your lovely, inspired book. Compliments to Ejah Rahim for the engaging review.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|