|

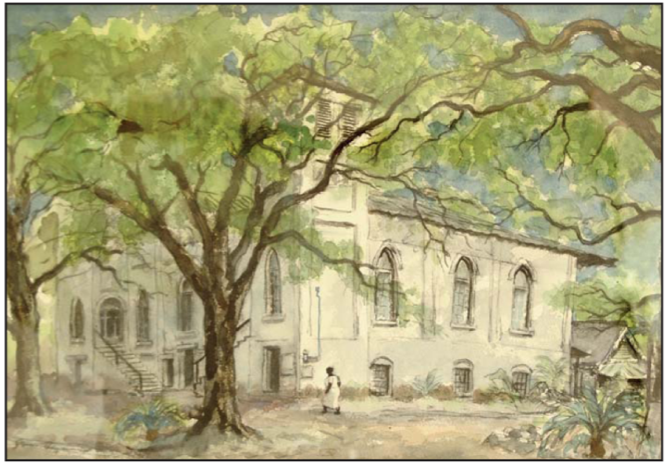

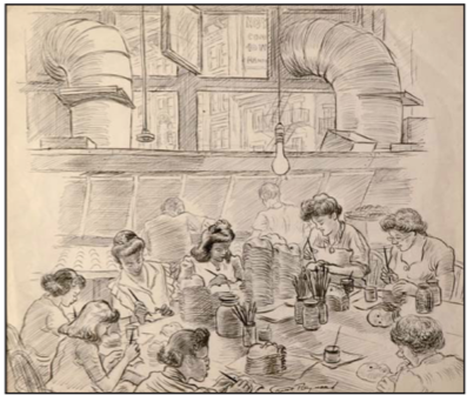

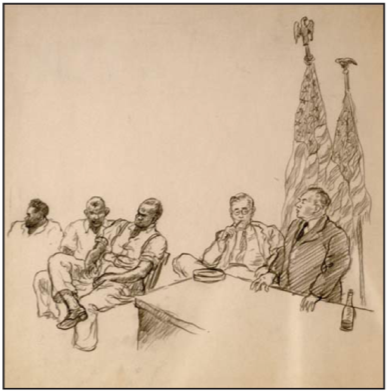

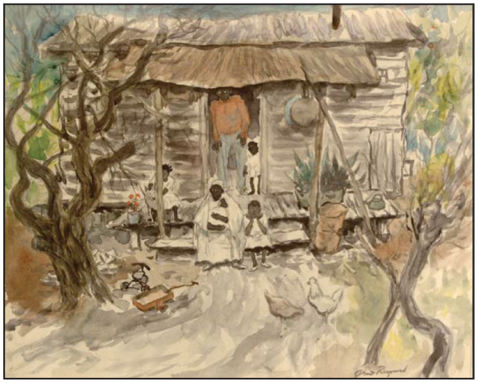

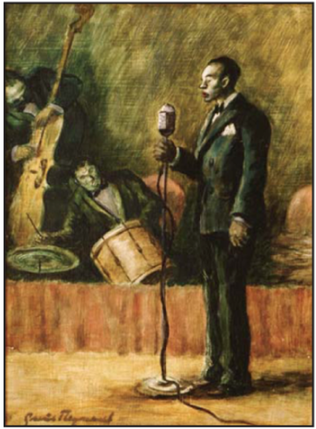

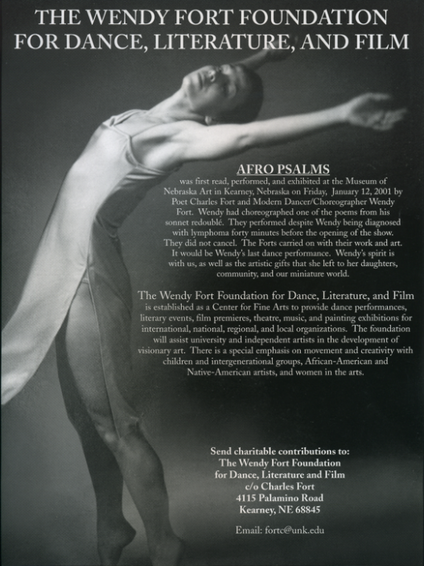

Afro Psalms I rehearsed and collaborated with my late wife Wendy Fort, dancer and choreographer, on Afro Psalms in the fall 2001, a year before her passing. Wendy was diagnosed with lymphoma 30 minutes before the performance. We drove quickly from the doctor’s office to MONA and decided our performance would go on. Wendy started treatment two days later. Mona’s curator slowly walked out before the audience of 300. Wearing white gloves, he placed a painting on the easel. I read one poem each time it settled on the easel. After I read the poem selected by Wendy to perform Stepping Out. Wendy received several standing ovations and applause that still linger in the halls of the Museum of Nebraska Art... It would be the last dance of her life. Her life too. I was co-curator. I chose 15 paintings and wrote a poem based on each painting, a sonnet-sequence. I titled the entire sequence Afros Psalms and titled each poem based on my observations and history depicted in the art. The paintings and poems were framed and shown during the opening and other events. Wendy’s memorial service (piano, music, poetry, reflections, and song) filled the grand hall of MONA. There were poster boards and graphics made by our two daughters, photographs, and dance performances. Ten years ago, one of your staff members sent me the original video of Wendy’s last dance. One of my student assistants filmed the entire Afro Psalms premier performance and the Memorial Service). I was able to capture the attached single photographs. Charles Fort "This series of paintings and drawings portrays the day-to-day lives of African Americans in the first half of the 1900s. The empathetic images, created by artist Grant Reynard (1887-1968), are given context by the historic recollections of the accompanying poetry by Charles Fort. Through the artwork and the sonnet redoublé inspired by it, the viewer may better understand the lives of African Americans in the early twentieth century." Museum of Nebraska Art, website Afro Psalms The woman slow-danced in Satan’s arms tossed a rose to a black man on a throne in love with a slave’s wish and circumstance undressed in the parlor before his kiss. The hunchbacked poet walked in the meadow until he memorized the King’s English dreamed in his fever of the crippled ghost who in his shame praised the woman he mourned. His wish was a source of the broken crown the journal written by God’s shaking hand and fires that smoldered in the great sea with the blood of the world cupped in his palms. They recited his wish, her love, his shame brooding in the shadow of Othello. Black Dolls, White Dolls The black women gathered parts of white dolls before the Supreme Court a young lawyer: black doll and white doll before a black child as the black child caressed the white doll face. The black child had seen beauty in God’s face before the headline news of a bombing and four girls killed at the Birmingham church freedom riders, riots, water hoses. What if the white women gathered black parts attached a white head to a black body or a gifted black head to a white body attached black beauty to the white beauty? Three doll eyes pecked out by a yellow crow the hunchbacked poet walked in the shadow. Justice Crime in the city became punishment in the field with the blindfelled crowd and a hooded soldier at ease like a coiled serpent taut as a bent cross on his armor. The lunatic and depraved left the cry quarter for the long march to circle the gallows as the hanging judge tore his bible and mused: Punishment in the field became crime in the city. Was it how we punished the wealthy who plundered, robbed, and killed or the poor and how many we killed Wearing their tar and feathers like a gift? Crime in the city became punishment in the field with quicksand and rope a foot too short. America Give us our poor king of the free who discovered truth every four years in a pickup truck and trailer park blues or his sharkskin suit at the juke joint bar. King of the free give us our poor who born to circumstance and keen design without the kettle of blueblood bedside diseased in heaven without a birthright. One black man in love with America polished the president’s silverware raw and one black man in hatred of thieves crawled the back alley and stirred the fat clean. Give us our poor moved to a burial ground his wish was a source of the broken crown. Stepping Out This was not a vogue it was jazz riff born out of a mud cart and wagon wheel into the twist the slide and the house fly from the lean genius of Louis Armstrong. There was coloured heaven at the movies and What a Wonderful World he laid down in a pin-stripped blue Easter suit wing-tip before James Brown fell down in a black cape. The swoon of the crooner and double bass born out of a slave’s wish and circumstance into a soft shoe dance and cocoa bop down home country blues into rock and roll. Dancers and singers gave up the seven mules as they beat the man with the pitchfork blues. Choreographed and Performed by Wendy Fort. In a Just and Miniature World It is a fearful thing to love What Death can touch. There were clear signals you were not well fourteen days and fourteen nights doubled over. The evening’s champagne was left unopened tied in blue ribbon like death’s bright palette. The horse drawn carriage arrived at midnight with pouches of a used and rare blood type as the devil’s fortune took the devil’s turn and catheters and picks left a territory of welts like the discarded stars falling in your eyes. The hooded driver passed the medicine bag to Dr. Bascom passed down by his grandfather who bowed to the South Dakota mountains wiped your forehead and took your rapid pulse. This was not a part of the evening news unequal to holy war and starvation of nations only comfort to a husband with two daughters left on the back porch with no crimes to unlearn who knelt together like angels on the great plains. There were clear signals you were not well with two weeks of doubt until they scanned your organs as the fog lifted over the Platte River a smoky black mushroom like a newborn stillborn known only as a case number left at the prom door. There was no wind in Nebraska on New Year’s Eve as the head nurse tapped your veins for the morphine until your white count rose and your platelets danced and your recovery made a good country doctor flinch after a distant signal found the artery of remembrance. ** After the Rehearsal We gathered your choreography of Afro Psalms our wedding vow performance on marbled floors at the Museum of Nebraska Art MONA To Its Friends. You practiced for hours at Harmon Park’s rock Garden raised by WPA flophouse workers free room and board for the farmers and artists the shapers of Central Nebraska’s Stonehenge. We gathered the African kalimba and rain stick metaphors of black magic and voodoo blood for our evening’s curtain call in the corn palace under a shower of circumstance and disease. Forty-five minutes before the poetry reading your dance and the art exhibit opening we were seated in the small doctor’s room half-alive in thin aluminum chairs among the scorched leaves in the hollow and the bright wings of the angel noble in their wild and hovering insignificance. It was the doctor’s first and correct call: I am sorry to have to tell you you have lymphoma. There was nothing to be said. We walked into the distant world thirty minutes until our performance. We would not tell our daughters tonight and we gathered our poems and music hollow instruments that moaned in our hands. As we arrived and hurried into the museum to a full house of literati and wise docents the sandhill cranes and life studies seemed alive with the avant-garde of the central great plains. You were stronger than the hunger of gravity and you had not doubled over for an hour and the strong medicine they gave you made you more of your second self. I saw the throttle of pain in your eyes with ten long minutes to show time. Our daughters Claire and Shelley sat in the front row with large eyes small hands and their larger hearts knowing something was wrong with you. They had stared into the devil’s wishing well as you walked on stage they wished you well. **

In Memoriam For Wendy Fort Twice they said you would not make it and you awakened like a small bird in its first dance outside its fallen nest. Husband, two daughters, and friends sat at your bedside at daybreak into the evening until each minute fell out of the heavens like gold coins in the lilac wild that were your eyes. Your chest rose and your breath fell and the night nurse detected a slight murmur in the parlors of your heart. It’s going to be all right mommy, shhh, shhh, Shelley whispered. They held your hands for hours as Shelley sang into your eyes that suddenly opened and you smiled and said to your daughters: I love you, write it in your journals. They wrote it in their journals in their bedrooms in your voice on your last day on earth before heaven you told Claire (16) and Shelley (12) you would speak to them in their dreams. What am I going to do without you without the walks to elementary school? I did not want you to walk me. it would be funny to my friends. What about our little dog Mojo in the park who leaped like a deer in the prairie grass behind the Windy Hills Elementary school? It’s going to be all right mommy, shhh, shhh, Shelley whispered. Claire screamed: I don’t want another Mom. She won’t see me graduate college married or dance in the meadow soft shoe with Barishnikov or Astaire. She will be gone forever. Claire comforted Shelley: You will be fine. You are beautiful. Wendy made you beautiful. There is nothing to fear. Afterwards in the afterlife you gave us the proper signals: Claire dreamed you had left us and the morning clock stopped. Weeks before your photograph that blew across the room with closed windows and without the Nebraska wind landed face up. Shelley wanted to play the violin for you and they found it in the dark locker halls. She played Cripple Creek by memory though her music sheets were in the case. Shelley’s last song for you to hear a symphony filled the hospital halls and lifted your spirit slightly from the hollow ground to higher ground. After I heard your last breath, Wendy, I awakened Shelley from the fold out bed and she touched your hollow chest. Do not worry Mom, it will be like meditating. You were gone. You asked: Where did she go? Can you close her mouth? The nurse closed your mouth. We walked down the hallway and drove out of the parking lot as Shelley wept in the backseat. I suppose it was Shelley’s young heart and age: We should have gotten a jar for her last breath finding something alive to trick death? Charles Fort The first five poems above are from Afro Psalms, an ekphrastic collection first published by Kearney, University of Nebraska, in 2001, and performed the museum. Many thanks to the Museum of Nebraska Art for the use of the artist's images. Charles Fort is the author of six books of poetry and ten chapbooks including: The Town Clock Burning (St. Andrews Press) and We Did Not Fear the Father (Red Hen Press). His work appears in 45 anthologies, including The Best American Poetry. Fort is Distinguished Emeritus Endowed Professor at the University of Nebraska at Kearney and Founder of the Wendy Fort Foundation Theater of Fine Arts. Poetry Honours and Awards include Yaddo Fellow, MacDowell Fellow, The Writer’s Voice Poetry Award Individual Artist Award in Poetry, Connecticut Commission on the Arts, Poetry Society of America Mary Carolyn Davis Memorial Award, the Randall Jarrell Poetry Prize, and more. Fort received the Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters, honoris causa, from Siena Heights University and Faculty Scholar Awards from the University of Nebraska at Kearney and Southern Connecticut State University, and he is represented on the NC Literary Map: Fort founded the Creative writing program at UNC-Wilmington. Fort has completed 350 villanelles. His first novel is forthcoming. https://www.poetcharlesfort.com/

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|