|

Caravaggio

Eyes that drink in the world -- how the hip bone juts under Christ’s taut skin as body is lowered into tomb, how two disciples, faces harrowed by labour, by suffering, brace him and it’s awkward, the way it would be, their faces the ones he lives among in Rome, in the poorer quarters, faces of peasants in the hills where he was a child, with their black-rimmed nails, their grimy bare soles no one else will paint and that get him in trouble, as do the whores, he makes into Mary, with milk-heavy breasts and too much cleavage, though churchmen still buy -- off the record -- for private pleasure, and as he honours men’s working hands so their bared torsos, unscarred and white as Carrarra marble but also doe-eyed, juicy boys as angels, minstrels or sun-flushed Bacchus. He honours violence too, the burn of it, the pride in his body’s tinder -- a tavern insult flaring into brawl and daggers drawn, into blooded streets. That pimp, Tomassoni, stabbed and dead, he’s on the run now -- Naples, Sicily, Malta -- painting in small rooms, back streets, his images bleaker, shallows of light, on black-brown fields -- the dark of well-rotted dung, of what lived broken down -- bitumen, ivory black, burnt umber -- his subjects wedged in a thin plane between frame and void. As is his David, holding at arm’s length Goliath’s severed head, mouth hanging open, roar gone, right eye ajar, death-clouded, the left wide, its rage still lit — his own likeness, his own face, while David, beautiful, looks a bit turned off but mostly sad, as if he knows, like us, where this is heading -- toward one last canvas -- where St. Ursula eyes the arrow stuck like a strange insect in her breast. And Caravaggio, eyes filmed, blind even, tilts his face to a light he’s letting go. Only one painting ever signed, as if with his finger, in blood. Susannah Lawrence Susannah Lawrence lives in northwest Connecticut, the rocky part. She holds an MFA in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Her work has appeared in Nimrod, The Cortland Review, The MacGuffin, Poet Lore, The Comstock Review and Green Hills Literary Lantern. Her full length collection, Just Above the Bone, was published in 2016 by Antrim House Press.

0 Comments

Stem Cell Hunting Season Ben’s hounds paw their chain-link pen, quit baying at his command. Inside his cabin he droops into an armchair—shaky, but not as weak as he was two months ago, his plaid flannel wrinkled as ever, cheeks sandpaper stubble. Above us hang four stag heads and an antler-wreath chandelier; over the door, a handsaw painted with a woodland scene. The first time I sat on his couch, I asked who mounted his bucks. “Taxidermist costs too much,” he declared. “Got ‘em at the Flea Mall.” Ben has hunted deer, bear, and wild boar since boyhood. Before Davy Crockett roamed these parts, settlers tracked wild creatures with bow and arrow, black powder, and firearms for food as much as sport. They still do. I’m city-born, but I respect the self-sufficiency bred in East Tennessee’s mountains. Around our cabins rove 640,000 acres of Cherokee National Forest. For twelve years Ben’s headlights have raked my window at 3:30 a.m., pickup crunching gravel on his way out with Bo, Blue, Big Boy, or just his fishing rod. It’s good to see him up and about since complications from diabetes and congestive heart failure pinned him to his bed. “I was goin’ down,” he confides. “Pain 24/7. Doctor talked hospice. I said hell, no. Got thirty million stem cells injected, from umbilical cord. After two weeks I felt better. The stem cells go wherever damage is—some to my heart, some to my knees. Even my cataract healed.” Conversation rambles to his bear hunt two weeks ago with B.J., the preacher up the road. They took along a young guy, a big talker. He put Blue—howling at prey—in peril by refusing to clamber through a gnarled thicket. Ben’s voice dripped scorn. It can take a man two days to crawl through a laurel hell. My friend has some years on him now, but he used to lunge down ravines, ford icy streams, creep across hells, trudge steep slopes. Ben backtracks. “The treatment is good for ninety days. I’m comin’ up on that. Cost me $7,000, not covered by insurance.” He pauses. “Need to decide whether to do it again.” I look up. On the log wall a rainbow of 200 fishing lures glints in morning’s sunstream. I’m like a walleye in Lake Tellico, beguiled by spinnerbait. In the dazzling tapestry, I spy a small, determined figure: Ben working his way uphill through stands of oak, hickory, walnut, elm, poplar, pine. Crossing glades wild with ginseng and rhododendron, the grape-scent of mountain laurel. Tracking higher into radiant birch, flaming maples, lacy hemlock. Cresting onto grassy balds. He is rising through his history, from childhood on to an engineering career, past a family feud, pausing now and then near dogs he’s buried, countless potlucks he has graced with smoked bear, stewed venison, fresh walleye, up to panoramas of ash-blue peaks. He casts his eye at the distant lake. Casts his rod across dark water, quiet and sure. Aims for what old-time hymns call Home. Gail Tyson Recent prose by Gail Tyson has appeared in Appalachian Heritage, Still Point Arts Quarterly, and Lowestoft Chronicle. Meadow Flowers (Goldenrod and Wild Aster)

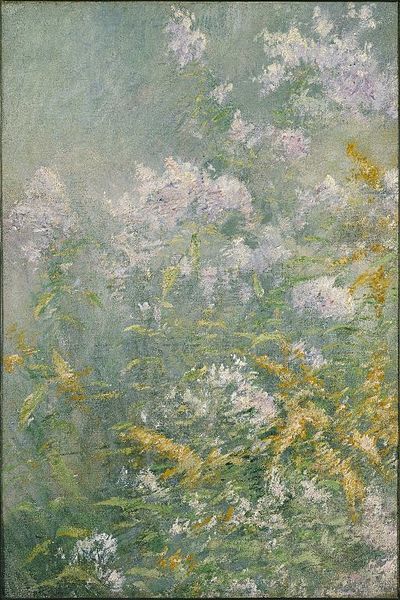

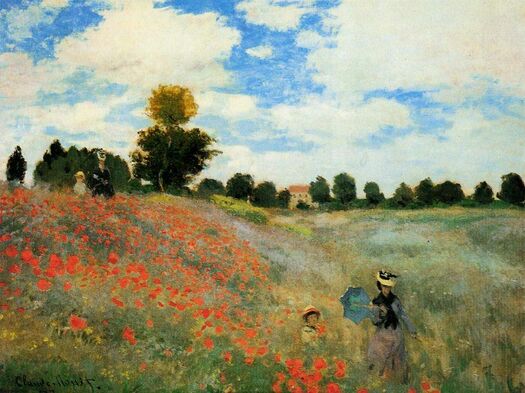

Like a gate to Paradise, illumined as how fluttering angels might appear, the meadow seems misty while at the same time impossibly bright. But there looks to be hardly any way into such purity of colour, through the many layers of lavender and yellow. And yet a few days before my father passed, he shouted for my sister to come quickly to his bedside. “Haven’t we found a new way of living?” he asked her. When she gathered herself and after being asked again, not knowing what he meant, she merely said, “No.” Though he insisted, “Yes, I think we’ve found a new way of living!” and went on tell her about an abundance of wondrous flowers he was seeing. Some years later, when another sister brought it up, I asked if she thought it had something to do with all the strong medicine he’d been taking. She thought not, rather that he was catching glimpses of heaven. Wouldn’t that be something though, if there weren’t the glittering cities and twenty-four karat streets thrumming with harp concertos-- no souls tipping diadems or flouncing in long robes, just the eternity of a second-chance earth flushed with asters and clusters of goldenrod? Wouldn’t we then become like the flowers too, our former sufferings blown from us as no more than light pollen into morning air? For this no doubt, we would want to let go, braced by the faith of flowers among those last, cold moments before being whisked into a valley of lemon lilies, or perhaps blessed with the surety of wild rose and camellias. Claude Wilkinson This poem first appeared in Claude Wilkinson's recent book, Marvelous Light (Stephen F. Austin State University Press.) Claude Wilkinson is a critic, essayist, painter, and poet. His poetry collections include Reading the Earth, winner of the Naomi Long Madgett Poetry Award, andJoy in the Morning, which was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. His most recent collection, Marvelous Light, was published by Stephen F. Austin State University Press. Death of the Virgin, Caravaggio, Louvre Dress rouge, hands big, misshapen, but his perspective always was slightly off to draw attention, make you look. Man behind and woman in foreground, heads bent in prayer so you do not stare at them, but at a face not the least beatific. A woman in sleep after a long day’s toil, face slightly ashen with a pearlescence, the belly protrudes. Always the virgin about to give birth-- and the alarm goes off one more time in a attempt to touch the Mona Lisa, crowd pulsing too much from the back-- ceiling draped in a cloth that points to feet, the least articulated, all the light near her face and bent third finger, working hands, hair auburn or the burn of end of summer in fields of grapes. Kyle Laws Kyle Laws is based out of the Arts Alliance Studios Community in Pueblo, CO where she directs Line/Circle: Women Poets in Performance. Her collections include Faces of Fishing Creek (Middle Creek Publishing), So Bright to Blind (Five Oaks Press), and Wildwood (Lummox Press). Ride the Pink Horse is forthcoming from Spartan Press. With six nominations for a Pushcart Prize, her poems and essays have appeared in magazines and anthologies in the U.S., U.K., and Canada. She is the editor and publisher of Casa de Cinco Hermanas Press. How to Cohabitate With a Kaleidoscope Rikki Santer Rikki Santer's work has appeared in various publications including Ms. Magazine, Poetry East, Margie, Hotel Amerika, The American Journal of Poetry, Slab, Crab Orchard Review, RHINO, Grimm, Slipstream, Midwest Review and The Main Street Rag. The writer's sixth poetry collection, Dodge, Tuck, Roll, was recently published by Crisis Chronicles Press.

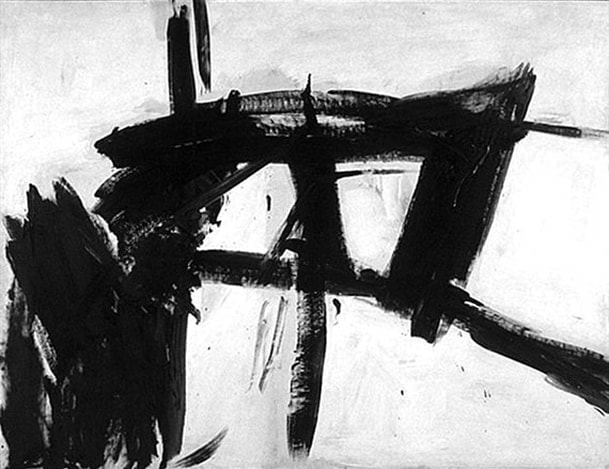

Temple Gate "Even in your Zen heaven we shan’t meet." Sylvia Plath, "Lesbos," 1962. This is the first gate that opens to my garden that leads to my temple Enter you will be offered tea by the ghosts of the suicides sitting in the plum trees singing you’re late you’re late but keep walking There are many gates of black and white to study like a critic or to pass through In the museum of heaven we may not meet Tricia Marcella Cimera Tricia Marcella Cimera is a Midwestern poet with a worldview. Her work appears in many diverse places — from the Buddhist Poetry Review to the Origami Poems Project. Her poem ‘The Stag’ won first place honours in College of DuPage’s 2017 Writers Read: Emerging Voices contest. Tricia lives with her husband and family of animals in Illinois / in a town called St. Charles / by a river named Fox / with a Poetry Box in her front yard. ** Vawdavitch by Franz Kline He knew where the dimensions meet, where dark invades the light; had seen the stark assault of harsh on soothing, the offensive by powers beyond our control. He had seen and he had rendered, his vision translated into violent brush strokes, put on canvas with ‘strident confidence’. With his sharp and rapid attack on our comfortable world, he forces us to reconsider our blind. amoeba-like passing through the contaminated waters of our limited lives. Rose Mary Boehm A German-born UK national, Rose Mary Boehm lives and works in Lima, Peru. Author of Tangents, a full-length poetry collection published in the UK in 2010/2011, her work has been widely published in US poetry journals (online and print). She was three times winner of the now defunct Goodreads monthly competition. Recent poetry collections: From the Ruhr to Somewhere Near Dresden 1939-1949 : A Child’s Journey, and Peru Blues or Lady Gaga Won’t Be Back. ** Forty-Thousand K Short Note: as per Artsy.net, as of 2012, the record high auction for Franz Kline’s painting Vawdavitch was $40 million at Christie's. A wise old owl once sat in a tree where nobody noticed him winking at me when he waved his right hand to attract my attention (I know—it’s a wing; I inferred his intention) and then with the other he stretched out a pinion which swept left to right across all his dominion-- though now, it would seem that my mind wasn’t right for in looking around there were no trees in sight; just chairs filled with people, some raising a hand, others nodding quite clearly, increasing demand for this bird front and center, much wanted by all, so intent on possession that none heard his call when his deep, owlish voice cried out “Who will it be?” If I’d had forty million, it would have been me. Ken Gosse Ken Gosse prefers writing light verse with traditional metre and rhyme filled with whimsy and humour. First published in The First Literary Review-East in November 2016, his poems are also in The Offbeat, Pure Slush, Parody, The Ekphrastic Review, and others. Raised in the Chicago suburbs, now retired, he and his wife have lived in Mesa, AZ, over twenty years, usually with a herd of cats and dogs underfoot. ** Extreme Unction Limp and lost in the vast Olympic night Javelin seeks the heart of an enemy, finds only limed collegiate grass. Net screams foul when ball slaps it. Kayak paddle captures racket, shoots rapids on the Colorado. They survive. Crampons secure, ropes tight, carabiners locked, peak and crevasse compete for sky. Afternoon shade splatters the field. Referees ponder: First down? Touchdown? Ground round? Ball rockets past hole, past green, past fairway, city, state, universe. Par is beyond the course. Violins ask to play through. The game so fast hoops run down the court, floor slats loosen, fly away, drive up the price of free throws. Booze, cigars, humiliation—dark swaths propel the ball on the meat of Mantle’s bat, of Marris’ bat-- even the Babe’s. Ref’s hand and arm chop violently behind his leg. Slashing so mighty the puck hides, trembles in the net. Skates shiny sharp as death. Pitch askew, the goal is chaos. The foot of God, not His hand, is required. Breath in patches, jersey splashed with sweat, the finish line is there, or there, or there, or there… . Winning/losing, soft/shrill, black meets white meets black meets white. One day it’s all gone. We disappear into dark, into light, not even a pebble remembers us. Charles W. Brice Charles W. Brice is a retired psychoanalyst and is the author of Flashcuts Out of Chaos (2016), Mnemosyne’s Hand (2018), and An Accident of Blood (forthcoming), all from WordTech Editions. His poetry has been nominated for the Best of Net anthology and twice for a Pushcart Prize and has appeared in The Atlanta Review, The Main Street Rag, Chiron Review, Fifth Wednesday Journal, SLAB, The Paterson Literary Review,Muddy River Poetry Review and elsewhere. ** At Last I need nothing more than this white canvas large housepainter’s brush and a can of black paint in this scarcity bare as any saint’s cloistered cell without distraction or elaboration I discover freedom each broad sweep of black redefining white in these limits the key to limitless infinity breaking and reshaping space my arm like god’s on the first day pulling new worlds out of the dark Mary McCarthy Mary McCarthy has always been a writer, but spent most of her working life as a Registered Nurse. She has had work appearing in many print and online journals, and has an electronic chapbook, Things I Was Told Not to Think About, available as a free download from Praxis magazine online. ** Aggression Muzzled Aggression muzzled can't be tamed. The soul restrained remains inflamed. The blunted blades of teeth denied will sharpen gnawing deep inside, becoming fiercely angled eye and ears erect to hear the cry that postured terror strikes in those who fear the will it might impose if ever loosed from reason's rein to wreak what now it's forced to feign, content to merely contemplate the vengeance that would compensate the liberty so long withheld and by such brutal means compelled. Portly Bard Portly Bard: Old man. Ekphrastic fan. Prefers to craft with sole intent of verse becoming complement... ...and by such homage being lent... ideally also compliment. ** Kline’s Headframe Headframe over a mine that could only be coal from where I started in Pennsylvania and left for a steel town in Colorado. The line down a cable to where a woman can scratch with pick in the hard earth, gone the superstition that her blood brings death. She digs for silver in Leadville before she becomes Baby Doe Tabor. I combed tailings for gold in Victor. Brutal work—when Dempsey swung fists in a nearby bar. Walk up the bed of narrow gauge through Phantom Canyon that brought coal from Florence to fuel cages of men with yellow fever down the shaft. Even hay fields of Kansas have the body of Vawdavitch, the up and down bob of wells that pump oil from the sturdy left side of the hoist. Kyle Laws Kyle Laws is based out of the Arts Alliance Studios Community in Pueblo, CO where she directs Line/Circle: Women Poets in Performance. Her collections include Faces of Fishing Creek (Middle Creek Publishing), So Bright to Blind (Five Oaks Press), and Wildwood (Lummox Press). Ride the Pink Horse is forthcoming from Spartan Press. With six nominations for a Pushcart Prize, her poems and essays have appeared in magazines and anthologies in the U.S., U.K., and Canada. She is the editor and publisher of Casa de Cinco Hermanas Press. ** A Beautiful and Brutal World The geese take off, wings whoosing against the white afternoon - skyward into the wind, dipping and alighting in the field near the Chevrolet dealership, blasting announcements for the Service Department. This new place for cars next to the traffic circle, expanding on all sides, has SUVs that look like they are smiling broadly. Near the intersection a man is holding a sign for help: anything will do in black letters scrawled big enough to be read. Disguising the mess of his life, he is grasping and reaching into a landscape of cars with drivers who gaze straight ahead. Meanwhile, one of the geese, head up and seemingly guarding the feeding flock, turns his head, like he is pointing at the man, his bicycle propped up against an orange cone. Whoever we are, this abstract environment expands us. We feel like the bicycle, like the geese, like the idling cars waiting for admittance. Nancy Wheaton ** Safe House startled like an owl, beak clattering in alarm, not knowing if harm would come taken in dark, awoken- then, as drugs wore off, then the unknown men on top never seen day, money, phone, could mean escape, clean sheets, warm baths, no-one demanding she leave herself- even when she did not know where she was Cleone T. Graham Naturalist, poet, and painter, Cleone Graham exuberantly explores the forests and coasts of Maine and New Hampshire. ** Not Understood Is this what it all boils down to? Even though you have stated it boldly in black and white, you have never intended to be understood. After all, being understood can be a risky business. Not understood, you are then not held captive to any specific interpretation that may raise speculations of autobiographical references (if those are things you abhor) or any other inconvenient scrutiny bordering on loss of privacy. In the book, The Madman, Kahlil Gibran wisely pointed out that "those who understand us enslave something in us." Has this ever resonated with you? I often wondered. Not understood, you can be at liberty to navigate between what you referred to as the positive negative spaces of your creation, your paintbrush responding with sweet authenticity to your secret ruminations, everything else being inconsequential. You may have painted a series of riddles but it is impossible to overlook the aura of enigma you have painted about you during the course of your brief career. Your altar of abstractions know no lack of offerings and especially of late....some have been generous. This I have understood. Ellen Chia Ellen exchanged her corporate heels for paintbrushes in 2007 and had since embarked on a journey from Singapore toThailand as a self-taught artist. When she is not painting, Ellen enjoys going on solitary walks in woodlands and along beaches where Nature's treasure trove impels her to document her findings and impressions using the language of poetry. ** My Black Spot A treasure island mark on a palm for which mam says she has blankets in the airing cupboard. For any metal crashes we might hear from the busy A one. A grey metal bridge over the spot I trundle my Raleigh bike to meet with crystal set Duncan, bright as the guards on his new bike. An overgrown cottage with walls like broken teeth and shattered windscreen glass meets me at the footbridge bottom. There is no blood, only what's left after the event. On return footbridge is now flyover, black spot removed. folk fly by too fast. My old home is a turn off. into village quiet. A place folk glance at On the way elsewhere. Paul Brookes Paul Brookes is a shop asst. Lives in a cat house full of teddy bears. His chapbooks are The Fabulous Invention Of Barnsley, (Dearne Community Arts, 1993). The Headpoke and Firewedding (Alien Buddha Press, 2017), A World Where and She Needs That Edge (Nixes Mate Press, 2017, 2018) The Spermbot Blues (OpPRESS, 2017), Port Of Souls (Alien Buddha Press, 2018) Forthcoming Stubborn Sod, illustrated by Marcel Herms (Alien Buddha Press, 2018). Please Take Change (Cyberwit.net, 2018) Editor of Wombwell Rainbow Interviews. ** I pace the street trace black lines around the block like a Kline.my past stacks up, chords through my mind.it’s only when I feel ghosts breathing do I do so myself.breathe.let the ghosts’ pasts complain.let me listen silent.it all[the colour]fades into monochrome.the cracks break&invade.or I invade them.sink into a past, not-mine.where what I did is irrelevant.when abandon meant a good thing. the sidewalk pushes back up at me at the exact weight I push down.we, like a team, encircle squarely.it’s not until I feel the ghosts do I feel the most settled into my awe.this city layered two-by-two with pasts.poets. artists.screaming do what you feel, damn the torpedoes.damn sense.like termite trails, pure creation traces these sidewalk lines—and I-- I’m with them.lock-step.trailing closely the urge.letting my own history die within their favor.permission.I am the mission.treat kindly the ghosts, a thing whispers. let self sink into the hard concrete.let the simple walking guide.be unto the city as it begot you. I feel this response.approval by the street lights & taxi screams.let this be my witnessing. Darren Lyons Darren Lyons is currently a creative writing MFA candidate at The New School. His poems have recently appeared in The Ekphrastic Review, Chronogram, and The Inquisitive Eater. A poetry/painting project of his was featured on The Best American Poetry Blog. One of his short stories and another poem were published in the 2016 and 2017 editions, respectively, of Stonesthrow Review. ** Getting There rushing up a bridge a cloudy day at gunpoint violent stroke ivory black geometry the palm the hand I’m not done yet getting there time’s structure a gash of metal pipe vertical becomes diagonal seeing through a window the coal blue black childhood orphanage what hangs could be a father figure a child’s crude game or the knife’s gesture as it kills Jessica Purdy Jessica Purdy holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Emerson College. Recently her poems have appeared in The Plath Poetry Project, The Light Ekphrastic, The Wild Word, and Bluestem Magazine. Her chapbook, Learning the Names, was published in 2015 by Finishing Line Press. Her books STARLAND and Sleep in a Strange House were both released by Nixes Mate Books consecutively, in 2017 and 2018. ** This is what remains of the barn after the fire-- aroma of barbecued beef, smell of spoiled milk. A haphazard array left upright citizens to bear witness an electric act of natural cleansing. Father too old to climb, replace lightning rod blown off during wild winter winds; too prideful to ask for assistance to get on top of things. At any cost, we should protect all mothers bearing milk and immunities. They bear the bounty-- nourishment of their species. If struck down, we lose. Yet my sisters and I stand here in Spring, thankful for rebirth, and one less asset to bear from an antiquated existence. Jordan Trethewey Jordan Trethewey is a writer and editor living in Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada. His work has been featured in many online and print publications, and has been translated in Vietnamese and Farsi. To see more of his work go to: https://jordantretheweywriter.wordpress.com or https://openartsforum.com. ** So-Called Abstract The door opens on its side and closes on its side. You can disagree, but there is no darkness deeper than the self. A weapon inexplicably cast at a right angle only makes sense to the flesh it pierces. I understand your fear, Franz; portraiture is an opera of glass, but even the most abstract artist can be identified by his hairline. When a bridge is constructed from a pile of branches be careful you aren’t looking for hidden meanings in the cracks. The light seeping through is nothing more than a sequence of shapes. Understanding gives way under our feet like feathers. The canvas is losing its integrity, slashed one too many times by the paint. Crystal Condakes Karlberg Crystal Condakes Karlberg is a middle School English teacher. She is a graduate of the Creative Writing Program at Boston University. Her writing has appeared in Mom Egg Review, The Compassion Anthology, Scary Mommy Teen, and her poem, "Winter Whale" was recently selected as the winner of Folded Word Press' Solstice Series 2018. ** Overcome by Art She really doesn’t get abstracts, but this Kline froze her in her tracks. Vawdavitch? What’s that? Sounds like a place in Eastern Europe. Menacing, full of misery, from the snow she can feel under her thin shoes to the charred fence with no sign of home. So much violence in the brush strokes! She imagines trains to Auschwitz or Birkenau shuffling past this scene. Remembers Daddy, who parachuted into battle, but found liberating death camps the worst horror of war. She smells the stench of the cattle car, sways back and forth, struggling to keep her balance. A blinding light! “Ma’am, Ma’am. You’re okay. You just fainted,” says the medic shining a flashlight in her eyes. Alarie Tennille Alarie’s latest poetry book, Waking on the Moon, contains many poems first published by The Ekphrastic Review. Please visit her at alariepoet.com. ** Landing on the Other Side My bones are white under my skin (also white-- but different, not bleached or hard--) and yet you answer by asking for eaten words, invoking crow-- (according to legend, once white too)--bearing omens, consumed by riddles. How far will, then what?—the black bird, the human, arms outstretched unfeathered above waters that drown the questions, quench courage. Spinning children of the moon!—(all shadows with the same skin--) What light lays bare, its absence enshrouds. Kerfe Roig A resident of New York City, Kerfe Roig enjoys transforming words and images into something new. Follow her explorations on the blog she does with her friend Nina: https://methodtwomadness.wordpress.com/ and see more of her work on her website: http://kerferoig.com/ ** Brushstrokes Up and across my monochrome cage Runs the dull ache that darkens life’s rage Competing with troubled thoughts The pain of my past that jabs at my wrist Is guided by fears that are part of the list That voice the sound of despair My memory is tinged with anger and rage And something to do with being that age Where you should not shed tears I channel the cries of my former strife As angular form that’s now part of my life That repairs to the broken thoughts Now that I know I have something to say People will know that this is my way To repair a damaged soul Henry Bladon Henry is a writer based in Somerset in the UK. He has a PhD in literature and creative writing and writes all types of fiction. His work can be seen in FridayFlashFiction, 50WordStories, thedrabble, ID Magazine and Writers’ Forum, among other places. He also runs a writing support group for people with mental health issues. ** The Emotion of a Painting: The Final Test Is this the text of a bold Japanese print maker? Or a drawing, perhaps, of a child of four gone magic-marker-wild, luxuriating in the strokes of his unpracticed hand? Marked by a child’s reckless glee? (I could show you my son’s paintings at four.) No, this Vawdavitch hails from Kline of Wilkes Barre, a place mere miles from my old Pennsylvania homestead. What drew me to his abstract message? It was the awareness of his anger, and perhaps my own; a warning that this anger must be treated with care, lest it consume us. In his virile strokes I saw the touch of Pollock, his seeming randomness. I saw the foreboding: the deep-dark, coal blackness against the white, Kline’s life robbed of a father, later a mother, and then a wife. While subways rumbled and smells of fresh rye bread pervaded the room, my friend’s Pollock hung in his foyer, at the end of a long kitchen. Haphazard, I’d have said in those days. But now I read more into these abstracts, Kline’s included. The premeditated strokes bespeak tumult, the chaotic artistic lives of New York’s 1960s, “flower” songs, Viet Nam, feminism, perverse sexual freedoms already erupting, the careless disregard for babies. In this Vawdavitch, the anger serves its purpose: the vindication for fatherless Kline, of all that wasn’t, but could have been. Carole Mertz Carole Mertz enjoys the lessons she receives from various artworks and the challenge of placing her reactions into comprehensible sentences. She has recent work at Dreamers Creative Writing, The Ekphrastic Review, Eclectica, Front Porch Review, Muddy River Poetry Review, Mom Egg Review, Quill & Parchment, WPWT, and elsewhere. Born in Pennsylvania, she now resides with her husband in Parma, Ohio. The Unfaithful Shepherd

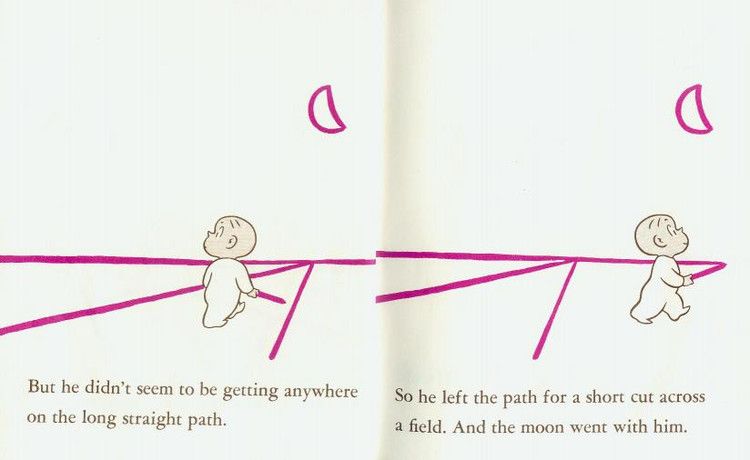

His brash tights tell the whole story: a taste for the garish, a longing for some lost joie de vivre that’s settled down into the swollen red sacks of his hose. See how they run-- lift and run as he goes, legs pounding like blood, carrying the doughy bulk of his body, a smile on his broad peasant face. Because this is homily, Brueghel inclines the bare field downward, gravity like sin, the ground rutted with last night’s rain; its tracks arrowing the direction the poor shepherd’s fleeing in. His sheep too are running away, their bodies soft white blurs of flight, like angels ascending into callous air. Now look to the right, the wolf’s already there, his muzzle stuck in the soft bowl of a newborn lamb . Whoever said, to live is not as easy as to cross a field must have known about nights surrounded by the warm fug of animal breath, where the wolves await, patient as death. Persistence another kind of faith. Jeanne Wagner This poem was first published in Able Muse. Editor's note: There is some confusion over the artist of the painting, as both father and son were artists with the same name of Pieter Bruegel. It is assumed today that the painting is by Pieter the Younger, and that it is a copy of the same painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, one that was lost. It may also be a follower or or student of the Elder: in these times, artists learned by copying their master's paintings. Jeanne Wagner is the winner of several national awards: most recently the Arts & Letters Award, The Sow’s Ear Chapbook Prize and the Sow’s Ear prize for an individual poem. Her poems have appeared in Cincinnati Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, Shenandoah, Southern Review and Hayden’s Ferry. She has four chapbooks and two full-length collections: The Zen Piano-mover winner of the Stevens Manuscript Prize, and In the Body of Our Lives, published by Sixteen Rivers in 2011. Perspective How far and how fast must I stride to step into the same river twice? The imaginative scope of Crockett Johnson’s children’s book Harold and the Purple Crayon, first published in 1955, seems deceptively simple. On the opening page we see only a little boy in white pajamas holding a purple crayon with which he’s drawn a short line from the left side of the otherwise blank page. The boy, Harold, looks up toward the empty space on the right side of the page. We’re told, “One evening, after thinking it over for some time, Harold decided to go for a walk in the moonlight.” I like it that Harold appears to have been thinking it over and that he’s looking at the empty space where a moon would have to be if he’s to walk in the moonlight. On the second page this absence is confirmed: “There wasn’t any moon, and Harold needed a moon for a walk in the moonlight.” We see Harold reaching up on tiptoes, drawing a crescent moon. We aren’t told that’s what he’s doing, but we can see him doing it and we’ve been given his motivation. “And he needed something to walk on,” we learn on the third page, and we can see that Harold has stretched that straight horizontal line across the page and is drawing a diagonal line away from it toward the bottom of the page. We realize that he is drawing something to walk on before we turn the page to be told, “He made a long straight path so he wouldn’t get lost.” Harold’s in the process of drawing the other side of the path, extending from the place on the horizontal line where the first vertical line started. We haven’t been told that the horizontal line has become the horizon in the landscape Harold is creating, but we intuitively know that it has. “And he set off on his walk, taking his big purple crayon with him.” With three straight lines and a crescent shape Harold has created a palpable world and somehow it makes sense that he would be taking a walk in it.

That fifth page shows Harold in the middle of two lines that start wide in the foreground and grow narrow to a point in the middle ground, where they meet each other and the horizon. Harold is the largest object in the image, his head and shoulders above the line for the horizon and only a narrow apple-slice moon in the blank upper half of the page. The sixth page has an almost identical image. The caption reads, “But he didn’t seem to be getting anywhere on the long straight path,” and we can see that it’s so. Harold looks to his left instead of his right, but otherwise the image is the same—the large figure of Harold, the wide path narrowing to the point on the horizon, the moon in the same spot. On the seventh page we’re told, “So he left the path for a shortcut across the field. And the moon went with him,” and we can intuit the motion—Harold holds his crayon at the end of a horizon line he draws as he walks along it, the moon still in the same place above him but the path now shifted to the left. On the eighth page we will see only Harold, his crayon, the horizon, and the moon. From here on his drawings become more ambitious and his wanderings more exciting, until finally he grows tired and starts to search for his bedroom window. He draws a great many windows, none of them the right one, and we may sense that Harold, who drew a straight path to keep from getting lost and later drew a single tree because he “didn’t want to get lost in the woods,” has some anxiety about being lost, unable to see his house or his window. Eventually, reassuringly, he remembers “where his bedroom window was, when there was a moon. It was always right around the moon.” He draws his bedroom window around that persistent moon and then, in a clever bit of wordplay, “Harold made his bed. He got in it and he drew up the covers. The purple crayon dropped on the floor. And Harold dropped off to sleep.” I’ve always admired how image and text work in surreal harmony throughout Harold and The Purple Crayon and I’m grateful to my grandchildren for exposing me to it again. But lately I’ve been haunted by those fifth and sixth pages, the ones where Harold is on the path. They seem almost like stills from a Winsor McCay cartoon like Gertie the Dinosaur or one of the Max Fleischer Out of the Inkwell shorts, where the hand of the artist is a part of the animation. If those two pages were cells in an animated cartoon and we set the sequence in motion, Harold’s legs would pump as he stayed in essentially the same position while the path would appear to move toward the bottom of the image, perhaps with flowers or bushes on either side starting out small in the distance and growing in size as they near Harold and then disappearing off the edge of the picture, making Harold seem to be progressing on his path. That’s the way cartoons animate linear one-point perspective, where there is a single vanishing point on or near the horizon, and in fact, in a video production of Harold and the Purple Crayon, that’s what happens. Perspective in drawings and paintings is a way of transferring a three-dimensional world to a two-dimensional medium by creating the sense of depth and distance we observe in life. A large figure in the middle of a wide path in the foreground of the picture seems near to us; a small figure nearer the point where the lines defining the path meet in the background seems distant. The very idea that there are foreground and background in the image indicates perspective. If the large figure has his back to us, we imagine him about to move off down that path, toward the small figure in the distance; if the small figure has his back to us, we think that he has already walked this path. If figures face us we think of them as coming or having come from the distant spot on the horizon. If Harold’s figure on page six were smaller than his figure on page five, while the path stayed the same size, we would think that he had made progress down that path. Had he stayed on it, a seventh page would have shown him smaller still, an eighth might have made him tiny, and we would expect him to disappear entirely by page nine. That’s perspective: things up close are larger, things in the distance are smaller, a path that begins with two parallel lines widely separated tapers to a point near the horizon. If we were able to extend the path in the foreground, so that it ran beneath us, it would be wider still, widest of all where we stand viewing the image. Look at it this way: for the figure with his back to us in the drawing and for the viewer—or for us in life who would be facing a real or metaphorical path in the same direction—the place in the foreground is now, the present, the place where we are, and the point on the horizon is eventually, the future, the place where we’re going. But what Harold reminds us, because the paths on pages five and six seem identical and he seems to be the same size and we know that in the first image he has “set off on his walk, taking his big purple crayon with him,” is that in the second image he should be on a different location on the path. That “he didn’t seem to be getting anywhere on the long straight path” is really a joke about perspective—in a still picture, anytime Harold is in the foreground on that path, no matter where on the path he might be in relation to where he was when he started out, the path and the horizon and the point of convergence would all look the same and he would not seem to be getting anywhere. The parallel lines that define the path in the foreground—in the now—are equidistant from one another all the length of the path; the lines only seem to converge in the distance; as you walk the path it is always the same width because you are always on it now and when you reach the point where the lines once seemed to converge—the place that one would arrive at eventually—you don’t run out of path or recognize it as the convergence point because it is still the foreground path, the path of now. Imagine Harold’s inverted V-shaped path, in essence an isosceles triangle, the baseline the bottom of the page. Label the widest part of the triangle, near the baseline, now; label the narrow end eventually. Picture Harold or any figure—or yourself—near now, looking off at eventually. This is the way we see our lives. If we place Harold or any figure or ourselves at the narrow end, as a tiny shape, we need to change the labels: eventually becomes now, now becomes then. In linear perspective in art the figure in the foreground can’t turn around and see where he’s come from, can’t visually locate then, but if he could he would see the wide end of the V that stands for now begin to narrow in the opposite direction, not widen indefinitely the way perspective seems to suggest, but taper to a distant point, as distant as eventually. That point would be then. For our tiny figure to turn around and look back, the triangle would need to shift direction—the wide end is always where we are, the narrow end is either where we’re going or where we’ve been. Only Janus, the Roman god of beginnings and endings,—think January—would be able to stand at now and see both then and eventually simultaneously, be able to appreciate a two-point perspective where the vanishing points are in completely opposite directions. With perspective we expect the large figure to get smaller the further we place him toward the vanishing point. Imagine what it would be like to remain that large figure to the end of the path, all the way to the horizon, stepping onto the point of convergence, reaching the end, the absolute eventually. It would be like the title character in The Truman Show thinking he’s sailing a vast open sea and thudding into the wall that has limited his life all along, without his awareness that it was there. It would be like the moment on pages 10, 11, and 12 of A Picture for Harold’s Room (a sequel to Harold and the Purple Crayon) when Harold, having drawn a small village on the horizon on a wall of his room, thinks it would look pretty in the moonlight, and so “stepped up into the picture to draw the moon.” On one page he stands large at the foreground of a long road in perspective leading to the tiny village and on the next he stands on the horizon, in the middle of the village, as large as he was on the previous page. “He looked down at the houses. ‘I am a GIANT!’ he said.” He exactly takes the position of someone who sees himself as a figure of now who has reached the vanishing point of eventually. That’s the problem with having to live in the now; it makes it hard to acknowledge the eventual or perhaps even the then. Is that what happens to us in life? We walk the path thinking we are still the large figure in the foreground until we smack into the wall above the horizon and look down to discover ourselves already—too soon—at the vanishing point. It may be that thinking in terms of one point perspective in regard to life or to destiny doesn’t really capture what happens in either of them. Isn’t life a long and winding road? On a winding road we may have no way to locate a vanishing point up ahead or one in the direction from which we’ve come; we may have only a vague sense of where a horizon may be. Instead, if we’re aware of anything, we’re aware of what we’re passing, what we see on the sides of the road, the scenery that limits our perspective. I think of the opening scenes in Jez Alborough’s rhyming picture book Duck in the Truck, where on the first page we see only the duck in his truck on a road in the woods and then on the second page see “the track that is taking him back,” a winding gravel road along a winding creek that does employ one point perspective to show us where the duck is going. But once we encounter “the rock that is struck by the truck” and “the muck where the truck becomes stuck,” we are shown only where the duck is now and his efforts to enlist others to get him back on track. Life is most often like that, where we’re stuck deep in the now, uncertain how to move on to a later now, with little awareness of where then or eventually might be or how much later each now is. Perhaps life is like a myriorama card game I have been long intrigued by called “The Endless Landscape.” In the version I have, there are twenty-four picture cards, each different from one another but having in common a river and a road. The cards can be strung together in whatever sequence the player chooses and in no particular order whatsoever, because however you juxtapose them, the river and the road in any one card will always line up with the river and the road in every other card. No card works specifically as a beginning card or a final card; there is no specific point of origin to move away from, no specific destination to arrive at; the limits are set simply by the number of cards available to be played. The road and the river go on and on until you run out of cards to lay down and without warning they end. If you were walking that road or floating on that river, in either direction, you would only notice the panel you’re in, not the panels ahead or behind; at either end you would simply step out of the final panel, simply, suddenly drop off. It’s possible to think of life in terms of one-point perspective, to think that we stand in the foreground of the present moment and are aware of the path before us narrowing and narrowing until, inevitably, we reach that vanishing point. Won’t we all reach that vanishing point eventually? If we look behind us, toward the background of our lives, can’t we recognize, if perhaps not remember, our origins at the vanishing point of then, before which we did not exist? And yet we don’t often think of our lives that way. Instead we tend to see ourselves as we see Harold on pages five and six, occupying the foreground. Unlike Harold, we don’t wonder whether we’re getting anywhere and don’t see a long straight path ahead of us that we’re not making any progress on. Our focus is always on where we are each moment rather than where we’ve been or where we might go; we live in now rather than in then or in eventually. Even then we make little effort to simply be in now; instead, a Buddhist might say, we worry about how to end a present difficulty or we worry about how long a present joy might last—instead, we struggle to imagine a different now than the one we’re in. Certainly that’s what Harold does, to the great pleasure of those who read about him, but it’s only at the end of the book, after he lets his anxieties drop behind him and he returns to his room and his bed, that Harold is at peace with where and when he is. Maybe it’s only when we seem to not be getting anywhere—when we stop worrying about getting anywhere—that we begin to see our lives in perspective. Maybe it’s only when we close our eyes on distant vanishing points and lose our sense of foreground altogether—when we let that large figure, that dominating awareness of ourselves, fade from the image—that we awaken to the present. However momentary that might be, maybe only then do we fully know the now we’re living in, realize where we are. Finally gain perspective. Robert Root Robert Root is an essayist, memoirist, editor, and teacher. He is the author of the album memoir Happenstance and the article “Essaying the Image” (The Essay Review, Fall 2014) and teaches a course in captioning and composing. He lives in Waukesha, Wisconsin. His website is www.rootwriting.com. Fate Preserved...

Behind the house the meadow looms that's also made of many rooms where treading feet have trampled halls and trees suggest surrounding walls and flowers now expectant wombs are splashing colours of their blooms against the grass they rise beside of greater reach as if to hide from tiny hands that cannot know that as bouquet they cease to grow except as beauty briefly seen amid arrangement where they lean to beckon fate they might preserve by oil and canvas they could serve. Portly Bard Portly Bard: Old man. Ekphrastic fan. Prefers to craft with sole intent of verse becoming complement... ...and by such homage being lent... ideally also compliment. Georgia O'Keeffe's Pattern of Leaves or Leaf Motif #3, 1923-4 I. They fill the frame, intense, close as a palm raised to your face. Deeply veined. Collage of layers. Background smoke. Three leaves overlaid, one on another. Bottom one, only ruffled edges—a gray-green shadow. Middle leaf, white as if furred with mold. The top dark maple the colour of merlot, in places almost black like dried blood. A vertical cut clean through the pulp, zigzag of lighting strike. Yellow in the wound. Break of sunlight. Exquisite. Obscene. A plump heart yanked from a body. II. A torn heart. III. The slash so clean hints leafcutter ants. Voracious hunger that consumes in minutes. Flesh-eating driver ants in The Poisonwood Bible. A village runs for the river. IV. Is it hard to paint violence? To form that jagged gash, nearly disconnect one half from the other? To scar beauty. Inflame it. Karen George Karen George is a retired computer programmer obsessed with art and photography, working on a poetry collection inspired by Frida Kahlo, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Emily Carr paintings. She’s author of five chapbooks, and two poetry collections from Dos Madres Press, Swim Your Way Back (2014) and A Map and One Year (2018), and her work appears at Adirondack Review, Louisville Review, Naugatuck River Review, Sliver of Stone, America Magazine, and Still: The Journal. She reviews poetry at http://readwritepoetry.blogspot.com/, and is fiction editor of the online journal Waypoints: http://www.waypointsmag.com/. Her website is: http://karenlgeorge.snack.ws/. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|