|

Perspective How far and how fast must I stride to step into the same river twice? The imaginative scope of Crockett Johnson’s children’s book Harold and the Purple Crayon, first published in 1955, seems deceptively simple. On the opening page we see only a little boy in white pajamas holding a purple crayon with which he’s drawn a short line from the left side of the otherwise blank page. The boy, Harold, looks up toward the empty space on the right side of the page. We’re told, “One evening, after thinking it over for some time, Harold decided to go for a walk in the moonlight.” I like it that Harold appears to have been thinking it over and that he’s looking at the empty space where a moon would have to be if he’s to walk in the moonlight. On the second page this absence is confirmed: “There wasn’t any moon, and Harold needed a moon for a walk in the moonlight.” We see Harold reaching up on tiptoes, drawing a crescent moon. We aren’t told that’s what he’s doing, but we can see him doing it and we’ve been given his motivation. “And he needed something to walk on,” we learn on the third page, and we can see that Harold has stretched that straight horizontal line across the page and is drawing a diagonal line away from it toward the bottom of the page. We realize that he is drawing something to walk on before we turn the page to be told, “He made a long straight path so he wouldn’t get lost.” Harold’s in the process of drawing the other side of the path, extending from the place on the horizontal line where the first vertical line started. We haven’t been told that the horizontal line has become the horizon in the landscape Harold is creating, but we intuitively know that it has. “And he set off on his walk, taking his big purple crayon with him.” With three straight lines and a crescent shape Harold has created a palpable world and somehow it makes sense that he would be taking a walk in it.

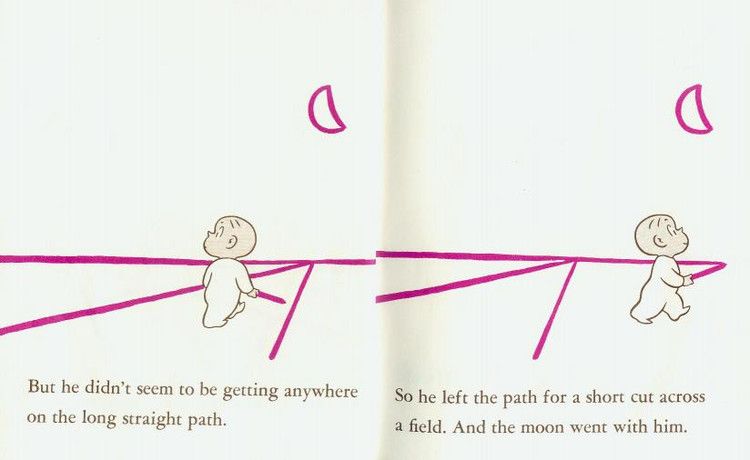

That fifth page shows Harold in the middle of two lines that start wide in the foreground and grow narrow to a point in the middle ground, where they meet each other and the horizon. Harold is the largest object in the image, his head and shoulders above the line for the horizon and only a narrow apple-slice moon in the blank upper half of the page. The sixth page has an almost identical image. The caption reads, “But he didn’t seem to be getting anywhere on the long straight path,” and we can see that it’s so. Harold looks to his left instead of his right, but otherwise the image is the same—the large figure of Harold, the wide path narrowing to the point on the horizon, the moon in the same spot. On the seventh page we’re told, “So he left the path for a shortcut across the field. And the moon went with him,” and we can intuit the motion—Harold holds his crayon at the end of a horizon line he draws as he walks along it, the moon still in the same place above him but the path now shifted to the left. On the eighth page we will see only Harold, his crayon, the horizon, and the moon. From here on his drawings become more ambitious and his wanderings more exciting, until finally he grows tired and starts to search for his bedroom window. He draws a great many windows, none of them the right one, and we may sense that Harold, who drew a straight path to keep from getting lost and later drew a single tree because he “didn’t want to get lost in the woods,” has some anxiety about being lost, unable to see his house or his window. Eventually, reassuringly, he remembers “where his bedroom window was, when there was a moon. It was always right around the moon.” He draws his bedroom window around that persistent moon and then, in a clever bit of wordplay, “Harold made his bed. He got in it and he drew up the covers. The purple crayon dropped on the floor. And Harold dropped off to sleep.” I’ve always admired how image and text work in surreal harmony throughout Harold and The Purple Crayon and I’m grateful to my grandchildren for exposing me to it again. But lately I’ve been haunted by those fifth and sixth pages, the ones where Harold is on the path. They seem almost like stills from a Winsor McCay cartoon like Gertie the Dinosaur or one of the Max Fleischer Out of the Inkwell shorts, where the hand of the artist is a part of the animation. If those two pages were cells in an animated cartoon and we set the sequence in motion, Harold’s legs would pump as he stayed in essentially the same position while the path would appear to move toward the bottom of the image, perhaps with flowers or bushes on either side starting out small in the distance and growing in size as they near Harold and then disappearing off the edge of the picture, making Harold seem to be progressing on his path. That’s the way cartoons animate linear one-point perspective, where there is a single vanishing point on or near the horizon, and in fact, in a video production of Harold and the Purple Crayon, that’s what happens. Perspective in drawings and paintings is a way of transferring a three-dimensional world to a two-dimensional medium by creating the sense of depth and distance we observe in life. A large figure in the middle of a wide path in the foreground of the picture seems near to us; a small figure nearer the point where the lines defining the path meet in the background seems distant. The very idea that there are foreground and background in the image indicates perspective. If the large figure has his back to us, we imagine him about to move off down that path, toward the small figure in the distance; if the small figure has his back to us, we think that he has already walked this path. If figures face us we think of them as coming or having come from the distant spot on the horizon. If Harold’s figure on page six were smaller than his figure on page five, while the path stayed the same size, we would think that he had made progress down that path. Had he stayed on it, a seventh page would have shown him smaller still, an eighth might have made him tiny, and we would expect him to disappear entirely by page nine. That’s perspective: things up close are larger, things in the distance are smaller, a path that begins with two parallel lines widely separated tapers to a point near the horizon. If we were able to extend the path in the foreground, so that it ran beneath us, it would be wider still, widest of all where we stand viewing the image. Look at it this way: for the figure with his back to us in the drawing and for the viewer—or for us in life who would be facing a real or metaphorical path in the same direction—the place in the foreground is now, the present, the place where we are, and the point on the horizon is eventually, the future, the place where we’re going. But what Harold reminds us, because the paths on pages five and six seem identical and he seems to be the same size and we know that in the first image he has “set off on his walk, taking his big purple crayon with him,” is that in the second image he should be on a different location on the path. That “he didn’t seem to be getting anywhere on the long straight path” is really a joke about perspective—in a still picture, anytime Harold is in the foreground on that path, no matter where on the path he might be in relation to where he was when he started out, the path and the horizon and the point of convergence would all look the same and he would not seem to be getting anywhere. The parallel lines that define the path in the foreground—in the now—are equidistant from one another all the length of the path; the lines only seem to converge in the distance; as you walk the path it is always the same width because you are always on it now and when you reach the point where the lines once seemed to converge—the place that one would arrive at eventually—you don’t run out of path or recognize it as the convergence point because it is still the foreground path, the path of now. Imagine Harold’s inverted V-shaped path, in essence an isosceles triangle, the baseline the bottom of the page. Label the widest part of the triangle, near the baseline, now; label the narrow end eventually. Picture Harold or any figure—or yourself—near now, looking off at eventually. This is the way we see our lives. If we place Harold or any figure or ourselves at the narrow end, as a tiny shape, we need to change the labels: eventually becomes now, now becomes then. In linear perspective in art the figure in the foreground can’t turn around and see where he’s come from, can’t visually locate then, but if he could he would see the wide end of the V that stands for now begin to narrow in the opposite direction, not widen indefinitely the way perspective seems to suggest, but taper to a distant point, as distant as eventually. That point would be then. For our tiny figure to turn around and look back, the triangle would need to shift direction—the wide end is always where we are, the narrow end is either where we’re going or where we’ve been. Only Janus, the Roman god of beginnings and endings,—think January—would be able to stand at now and see both then and eventually simultaneously, be able to appreciate a two-point perspective where the vanishing points are in completely opposite directions. With perspective we expect the large figure to get smaller the further we place him toward the vanishing point. Imagine what it would be like to remain that large figure to the end of the path, all the way to the horizon, stepping onto the point of convergence, reaching the end, the absolute eventually. It would be like the title character in The Truman Show thinking he’s sailing a vast open sea and thudding into the wall that has limited his life all along, without his awareness that it was there. It would be like the moment on pages 10, 11, and 12 of A Picture for Harold’s Room (a sequel to Harold and the Purple Crayon) when Harold, having drawn a small village on the horizon on a wall of his room, thinks it would look pretty in the moonlight, and so “stepped up into the picture to draw the moon.” On one page he stands large at the foreground of a long road in perspective leading to the tiny village and on the next he stands on the horizon, in the middle of the village, as large as he was on the previous page. “He looked down at the houses. ‘I am a GIANT!’ he said.” He exactly takes the position of someone who sees himself as a figure of now who has reached the vanishing point of eventually. That’s the problem with having to live in the now; it makes it hard to acknowledge the eventual or perhaps even the then. Is that what happens to us in life? We walk the path thinking we are still the large figure in the foreground until we smack into the wall above the horizon and look down to discover ourselves already—too soon—at the vanishing point. It may be that thinking in terms of one point perspective in regard to life or to destiny doesn’t really capture what happens in either of them. Isn’t life a long and winding road? On a winding road we may have no way to locate a vanishing point up ahead or one in the direction from which we’ve come; we may have only a vague sense of where a horizon may be. Instead, if we’re aware of anything, we’re aware of what we’re passing, what we see on the sides of the road, the scenery that limits our perspective. I think of the opening scenes in Jez Alborough’s rhyming picture book Duck in the Truck, where on the first page we see only the duck in his truck on a road in the woods and then on the second page see “the track that is taking him back,” a winding gravel road along a winding creek that does employ one point perspective to show us where the duck is going. But once we encounter “the rock that is struck by the truck” and “the muck where the truck becomes stuck,” we are shown only where the duck is now and his efforts to enlist others to get him back on track. Life is most often like that, where we’re stuck deep in the now, uncertain how to move on to a later now, with little awareness of where then or eventually might be or how much later each now is. Perhaps life is like a myriorama card game I have been long intrigued by called “The Endless Landscape.” In the version I have, there are twenty-four picture cards, each different from one another but having in common a river and a road. The cards can be strung together in whatever sequence the player chooses and in no particular order whatsoever, because however you juxtapose them, the river and the road in any one card will always line up with the river and the road in every other card. No card works specifically as a beginning card or a final card; there is no specific point of origin to move away from, no specific destination to arrive at; the limits are set simply by the number of cards available to be played. The road and the river go on and on until you run out of cards to lay down and without warning they end. If you were walking that road or floating on that river, in either direction, you would only notice the panel you’re in, not the panels ahead or behind; at either end you would simply step out of the final panel, simply, suddenly drop off. It’s possible to think of life in terms of one-point perspective, to think that we stand in the foreground of the present moment and are aware of the path before us narrowing and narrowing until, inevitably, we reach that vanishing point. Won’t we all reach that vanishing point eventually? If we look behind us, toward the background of our lives, can’t we recognize, if perhaps not remember, our origins at the vanishing point of then, before which we did not exist? And yet we don’t often think of our lives that way. Instead we tend to see ourselves as we see Harold on pages five and six, occupying the foreground. Unlike Harold, we don’t wonder whether we’re getting anywhere and don’t see a long straight path ahead of us that we’re not making any progress on. Our focus is always on where we are each moment rather than where we’ve been or where we might go; we live in now rather than in then or in eventually. Even then we make little effort to simply be in now; instead, a Buddhist might say, we worry about how to end a present difficulty or we worry about how long a present joy might last—instead, we struggle to imagine a different now than the one we’re in. Certainly that’s what Harold does, to the great pleasure of those who read about him, but it’s only at the end of the book, after he lets his anxieties drop behind him and he returns to his room and his bed, that Harold is at peace with where and when he is. Maybe it’s only when we seem to not be getting anywhere—when we stop worrying about getting anywhere—that we begin to see our lives in perspective. Maybe it’s only when we close our eyes on distant vanishing points and lose our sense of foreground altogether—when we let that large figure, that dominating awareness of ourselves, fade from the image—that we awaken to the present. However momentary that might be, maybe only then do we fully know the now we’re living in, realize where we are. Finally gain perspective. Robert Root Robert Root is an essayist, memoirist, editor, and teacher. He is the author of the album memoir Happenstance and the article “Essaying the Image” (The Essay Review, Fall 2014) and teaches a course in captioning and composing. He lives in Waukesha, Wisconsin. His website is www.rootwriting.com.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|