|

Adam at the Art Institute

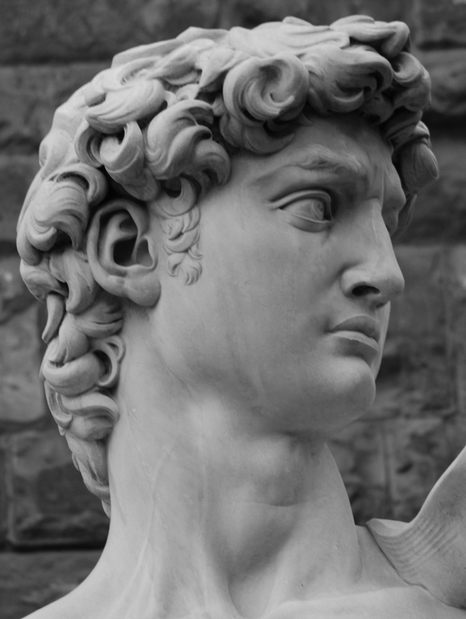

Rodin’s Adam stands at the top of the stairs, more than life-size, looking as if he’s about to throw something. His left arm rests on his bent right leg; his right arm reaches back, as if gaining momentum for the release of some (invisible) object. The pose reminds me of the fifth-century Roman sculpture the Discus Thrower. To duplicate the discus thrower’s stance, all he needs to do is raise that right arm farther up behind him, bend his shoulders a bit more forward, and grip his fingers around a round metal plate. And wipe that sad expression off his face. Adam is my neighbour at the Art Institute, where, as a volunteer, I sit at an information kiosk explaining to visitors how to find the American wing, or the Picassos, or the toilet. Visitors flow steadily up and down the Grand Staircase, many of them pausing to ponder Rodin’s depiction of their earliest ancestor. Often they say something to me as they do so: “Look how big his head is,” or “Where’s Eve?” or “That position looks awkward.” They bend to read the label, which explains that Rodin based the figure on Michelangelo’s portrait of Adam in the Sistine Chapel. There, a newly created Adam reclines, his index finger receiving the breath of life from God’s extended fingertip. But Rodin has tipped him upright, as if to say, “Time to be up and about. Let’s look at what we’ve got here.” What we’ve got, though, doesn’t look too good. Adam has caved in on himself, eyes cast down, as if he’s contemplating his own flawed flesh. His right arm reaches not out toward God but downward, and his index finger—in Michelangelo’s depiction nearly touching God’s—now points uselessly toward the earth. Although he seems poised for action, his feet are glued to the statue’s base. If he were to move, it’s easier to imagine him toppling over than actually completing whatever motion he’s embarked on. But then, Adam is all about toppling. Rodin originally sculpted the figure to be paired with Eve at a portal entitled The Gates of Hell, the Art Institute website explains. Rodin’s inspiration was Dante’s Adam, who, before being raised to the left side of God, spent thousands of years in Limbo. His “agonized body,” we’re told, “strikingly conveys the sufferings caused by original sin.” Rodin’s version may aspire to the fluid power of the Discus Thrower, but his muscles are knotted, his hands and feet too huge and ill-proportioned for grace. Those feet anchor him to the earth to which his sin has bound him (Adama: earth, in Hebrew), and on which he’ll now have to labour. Adam’s awkwardness (old Norse: turned the wrong way) is, I think, why so many visitors stop not only to contemplate but also to interact with him. Adam’s twisted pose pulls visitors in, as if they feel his knotted muscles in their own bodies. I’ve seen multiple young men imitate his pose, swaying unsteadily as their friends take pictures. I’ve seen one man link an index finger through Adam’s, as if in solidarity, and another rest a hand on Adam’s calf as he posed for photographs. When I saw the man touch Adam’s leg, I thought of intervening: everyone knows, after all, you’re not supposed to touch the art. But I figured by the time I rebuked him, he’d have removed his hand. In any case, I was touched. I thought of Lincoln’s head at Springfield, his nose shiny from the touch of passersby, and thought perhaps Adam, more than any other work of art, should bear the mark of his fellow creatures’ caress. Museums offer a charged space in which sparks of affinity leap between viewer and object. Watching these intense responses to art, I feel like a lucky witness to the best that human beings can be: curious, receptive, eager, kind. They connect with each other—and me—as well as with what they see: a husband, pushing his wife in a wheelchair, reads her the labels she can’t see; a woman excitedly points out to her friend the Frank Lloyd Wright window suspended from the ceiling above me; a young man high-fives me when I give him a flyer about our mini-tour based on Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. I even become a strange kind of confidante, to whom they trust their uncertainties. Not just “Where is the nearest rest room?” But, “These are all replicas, aren’t they?” “You mean this is the only real American Gothic?” “Haven’t I seen a painting of Van Gogh’s bedroom somewhere else?” I thrum with sympathy, listening to these questions. What does “original” mean, after all, given that artists often paint or sculpt the same thing more than once, and that sculptures are cast multiple times, sometimes after the artist’s death? In how many different places have I seen Rodin’s Balzac? There’s our own, a naked figure in Gallery 201, whose crotch melts between his legs into what looks like a traffic cone; there’s his sibling, perched identically in the sculpture garden of the Baltimore Museum of Art; and there’s the massive, enrobed figure striding through the garden of the Rodin museum in Paris. Each question strikes me as complex and worth thinking about. “What makes a painting get so famous?” a young man asks me, after I explain where he can find Grant Wood’s American Gothic. Even “where is the nearest toilet?” requires a thoughtful, contextualized response. “What did you want to see on the way there?” I ask. But man, alas, is a fallen animal. That couple I thought was passionately discussing Rodin’s Adam is in fact quarreling about when to get lunch. “We’ve already waited six hours,” one insists, as loudly as you can in a museum without drawing the attention of a guard. “Let’s go.” And then there was the wealthy looking middle-aged couple who paused to ask me directions. “How do I get to the modern wing?” the woman asked. I told her. “How do I get to the armour?” the man asked. The woman re-inserted herself in the conversation before I could answer. “We’re not going to see the armour,” she said disgustedly. “We’re going straight to the modern wing.” The husband, ignoring her, asked me again, “How do I get to the armour?” “Go straight, behind the Caillebotte,” I said, in my standard explanation, “until you see furniture on the right. Then turn right and keep going.” The woman turned to go, but then paused and looked at me angrily. “You’re fired,” she said. I smiled politely and glanced at my neighbour Adam to see how he was taking it. He was, as usual, looking at his feet. His sad expression said all that needed saying. Ruth Hoberman Ruth Hoberman retired recently after thirty years as a Professor of English at Eastern Illinois University. She taught and published on modern British literature. Her 2011 book Museum Trouble: Edwardian Fiction and the Emergence of Modernism (U of Virginia P) focused on the depiction of art and museums in early twentieth-century literature. Her poems have appeared in [PANK], Natural Bridge, Spoon River Poetry Review, and Iron Horse Literary Review. Three poetic texts about time, beauty, but not only...

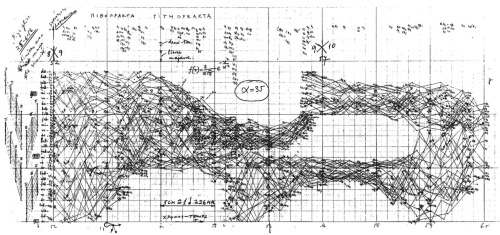

Part One (Epigraph Included) 27 So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them. The Holy Bible. Genesis 1 (King James Version) 7 And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul. The Holy Bible. Genesis 2 (King James Version) God created man in one day. In the image of God He created him. We can only guess, How aesthetically perfect Was that man, created by God, Before his fall, I mean. In the Old Testament, Genesis, Chapter 1, there is a verse: 31 And God saw every thing that he had made, and, behold, it was very good. And the evening and the morning were the sixth day. We believe it. And there is nothing to be added. As for the time, we must note, That astronomical time of the Old Testament, Especially concerning creation of visible world, Does not correspond to modern time. To sum it up: God, Dust of the ground, One day, Perfect man. Part Two Times not that old. The very beginning of XVI century. Renaissance. Florence. Michelangelo Buonarroti begins and, In about four years, Finishes his “David”. Marble sculpture of King David of the Old Testament, Believed to be a culmination of human genius. To sum it up: Man, Stone, Four years, Marble copy of man. Part Three In this case it is all too plain and trivial. Though there is, without any doubt, Some private pathos of this event, Mystery of impregnation, mystery of birth, Joy of fatherhood, joy of motherhood and stuff. Just like it is today. But still. Second half of XX century. The USSR, already not Russia. A big industrial city… (there can be further details to infinity). But let’s be brief… A boy is born in a natural way, As hundreds of billions of men before him, Descendants of those, Old Testament Adam and Eve, Expelled from the Garden of Eden. To sum it up: A couple of heterogeneous humans, In a natural way, Nine months, Not David, Naturally. Facts only, nothing personal. Alexander Limarev This poem was first published by Silver Birch Press. Alexander Limarev, freelance artist, mail art artist, poet and curator from Russia. Participated in more than 400 international projects and exhibitions.His artworks as well as poetry have been featured in various online publications including EXPOESIA VISUAL EXPERIMENTAL, THE NEW POST-LITERATE: A GALLERY OF ASEMIC WRITING, UNDERGROUNDBOOKS.ORG, BOEK861, TIP OF THE KNIFE, BUKOWSKI ERASURE POETRY ANTHOLOGY (Silver Birch Press), KIOSKO (libera, skeptika, transkultura), SIMULACRO, ZOOMOOZOPHONE REWIEW, ICONIC LIT, M58, METAZEN, UTSANGA, MAINTENANT etc. Iannis Xenakis, Pithoprakta for Two Trombones, Strings, Xylophone and Woodblock (1955-6) for Nouritza Matossian the spontaneous architecture of clouds efflorescences of glissandi the probabilistic polyphony of miniscule chaoses within chaoses col legno frappé col legno frotté arco bref arco normal rainbow of pizzicati Brownian molecular motion a cloudy palimpsest beneath micro-wars of insects and continent-wide armies sometimes irregularly in-step sometimes breaking step on bridges in case collective resonance causes them to collapse all is massing towards an entropic future comprehended by no god except music and a Maxwell-Boltzmann formula Jonathan Taylor Note: this poem is inspired by the description of Pithoprakta in Noritza Matossian, Xenakis (Nicosia: Moufflon, 2005). Jonathan Taylor's books include the novels "Melissa" (Salt, 2015) and "Entertaining Strangers" (Salt, 2012), the memoir "Take Me Home" (Granta, 2007), and the poetry collection "Musicolepsy" (Shoestring, 2013). He is Lecturer in Creative Writing at the University of Leicester. His website is www.jonathanptaylor.co.uk." Half-Naked Woman with a Coin The view is simple: a whore in cerulean. I’m not looking at you, but asking you to look where my eyes are pointing: first at my breasts, then to the coin in my hand. Make yourself comfortable- you won’t be listening, my mouth does the talking. Look-it’s approachable, just slightly open between teeth barely visible you’ll see a supplicant bit of tongue, glistening within. My left side, you’ll avoid it’s draped deep in the sheen of dropsy folds soon fallen. You’ll not see what I mean to keep hidden, under budding breasts, pushing up like soft pigeons. Heather M. Nelson Heather M. Nelson says: "I'm a poet, teacher, mother and recovering attorney based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I studied writing under the poet C.D. Wright as an undergraduate at Brown University. Most recently I have studied poetry with Tom Daley and Barbara Helfgott Hyett. I am a member of Poemworks, the workshop for publishing poets. My work has appeared in Constellations and The Somerville Times." Women in Red Dresses

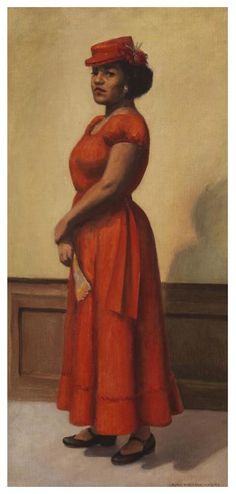

Here a strappy dress ready to dance, the girl’s cheeks red as her bodice, hands on the knee she’s drawn up on the seat, big black stone on her finger; and there an upright and angle-length red, neckline not too low, matching brimmed hat coming from Sunday services in the mary janes she polished this morning; and for Marian, a soft red gown off the shoulders, single strand of gold against her dark skin as she waits for the cue, door opening to the stage where she’ll let loose her voice to sing of liberty and her forefathers’ deaths—sing so her fathers can live again, their stories and their torn shirts offered to those who had almost forgotten, who had hoped too much, who will weep to hear. Susanna Lang Susanna Lang’s most recent collection of poems, Tracing the Lines, was published in 2013 by the Brick Road Poetry Press. Her first collection, Even Now, was published in 2008 by The Backwaters Press, followed by a chapbook, Two by Two (Finishing Line Press, 2011). A two-time Hambidge fellow and a recipient of the Emerging Writers Fellowship from the Bethesda Writer’s Center, she has published original poems and translations from the French in such journals as Little Star, New Letters, december, The Sow’s Ear Poetry Review, Blue Lyra Review, Prime Number Magazine and Poetry East. Book publications include translations of Words in Stone and The Origin of Language, both by Yves Bonnefoy. She lives in Chicago, where she teaches in the Chicago Public Schools. Carol Barbour is a poet, visual artist and curator. Her work has been published by Transverse Journal, Sein und Werdun, The Fiddlehead, Toronto Quarterly, Impulse, and Matriart. She holds an MA in art history from University of Toronto and an AOCA from the Ontario College of Art. A collection of poetry is forthcoming from Guernica Editions.

|

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|