|

Sunday Morning

Hymns unsung, prayers unsaid, I sat by the window and prayed for forgiveness one more time; one more time I begged. Holding the cup of coffee in my hand, I hoped the warmth would fill me where your words had left me cold, but I knew nothing could do that-- fire can burn for hours and be unfelt. Hymns unsung, prayers unsaid, I lay down on the empty bed, pulling the blanket across my cheek, turning from the window, from the sky and the sun, praying for some rest. Mary Kendall Mary Kendall lives in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Her current work and publications can be found on her writing blog, A Poet in Time (www.apoetintime.com). She is the author of a chapbook, Erasing the Doubt (2015) and co-author of A Giving Garden (2009).

0 Comments

In Cézanne’s Les Grandes Baigneuses flesh once again sings itself solid where a sapphire river mates with the hearing eye Titian Tintoretto Rubens rise again in oils from Impressionism’s shimmer: sculpted clouds trees vaulting over flesh’s density the correspondences: taste seeing touch sounding (as Baudelaire sang) Faces’ androgynous blurs bodies articulate symmetries in groupings of five and eight rendering poetry and painting each other’s semblances and frères After seven years’ labour he leaves the work unfinished Susan McCaslin This work is a segment of a book-length sequence of poems on Paul Cézanne to be published by Quattro Books in Toronto in Oct. 2016. Susan McCaslin is the author of thirteen volumes of poetry and nine chapbooks. She completed her Ph.D. at UBC in 1984 and taught at Douglas College in B.C. in the English and Creative Writing Departments for twenty-three years. Most recently, Susan has published a memoir, Into the Mystic: My Years with Olga (Toronto: Inanna Press, 2014), a spiritual autobiography exploring the sixteen-years she spent as a young woman learning from Olga Park, an elderly mystic from Port Moody, British Columbia. Her most recent volume of poetry, The Disarmed Heart (Toronto: The St. Thomas Poetry Series, 2014), explores the roots of violence and peace-making in the individual, the community, and the world. Her previous volume, Demeter Goes Skydiving (2012), was short-listed for the BC Book Prize (Dorothy Livesay Award) and the first-place winner of the Alberta Book Publishing Award (Robert Kroetsch Poetry Book Award) in 2012. Departures

I can't stop talking about mother, for example. The way stray dogs turn her eyes into a pool of fear, and how at the doctor's, she reads aloud without getting it right. Probably fear is a text that you learn to read better with each passing attempt. It's like a river turning into a flood, lonely in its seizure when amputee bridges and wrecked boats lead nowhere like allies in a losing battle – starvation is a river without boys diving in summer. And when it grows big, remember the old man out on the sea, the sun hiding at the tip of his harpoon, and all he tries to read is the fear in his own eyes, as the receding shoal of fish turn into a station - one designed only for departures. Aditya Shankar Aditya Shankar is an Indian English poet and flash fiction writer living in Bangalore. His work has been published or is forthcoming in Dead Snakes, Synchronized Chaos, 101 words, Hour After Happy Hour Review, CC&D, ‘Purrfect’ Poetry, Beakful, Shot Glass Journal, Earthborne, Terracotta Typewriter, and Eastern Voices anthology, among others. He is the author of a poetry chapbook ‘After Seeing’ (2006) and a poetry collection ‘Party Poopers’ (2014). Ali Rashid

Critic Irving Sander wasn’t initially interested in art. But he happened upon a Franz Kline painting and couldn’t get it out of his mind. Upon reflecting on how art provoked such profound and intense emotional responses, he concluded that art, in a way, “has magical powers, like a fetish, icon, or reliquary…The art object can literally bewitch the viewer. Casting a spell, it can transform him or her- that is, summon up a fresh perception of art, life and the world, and even cause the viewer to feel, think, imagine, and act in new ways…” I too am bewitched by the captivating, mythical, mesmerizing effects of art. Indeed, this is exactly the reason I obsessively comb the Internet, pore over my library of art books, and scour galleries and museums. I got hooked on that magic. Some art is a visceral, albeit, cheap thrill, and its rush fades fast. Other art lingers, coming up time to time in the unconscious like a spectre rising over submersion, calling like a loon over a deep lake and flashing silver light into your own dark waters. The work of Ali Rashid seems to transcend still all of this. With a few sprinkled colours dancing on a monochromatic backdrop, the paintings might be pleasant but unassuming abstractions, perfectly decorative. But instead, somehow, they conjure Babylonian tablets and secret codes; symbology systems, ancient records and desert topographies. As if over millennia, there are wear marks and peeling textures and scratches that suggest mythologies older than time itself. But what are they? “Some years ago I visited a small island near the coast of Syria and there I saw walls that were, so to speak, talking to me,” wrote Wouter Welling on Rashid’s webpage. “Children had painted their own hands as signs of protection on the walls. The paintings of Ali Rashid reminded me of those walls filled with vivid signs. One doesn’t have to be able to read the signs to feel that they are bearers of meaning.” Indeed, Rashid was born in Iraq, where the mists of time cloak the earliest human writings we know of, cuneiform code systems from Sumer. Welling recounts Rashid telling him how his work began. Living under the savage dictatorship of Saddam Hussein, and a soldier in the war against Iran, Rashid was writing in his notebook when he realized his words could put his life in danger. So he began drawing over the text, “in the process of course making the text unreadable. Layer upon layer he created later on paintings like a palimpsest, a way of adding time to the essence of the work. Rashid developed a poetic use of signs which relates him to artists such as Antoni Tàpies and Joan Miró.” “Ali's drawings are a shocking memorial to the atrocities which took place,” says writer T.J. Bruder for Underground Magazine. Rashid spent ten years in hell, a pawn of two cruel dictators. Sending artists like Rashid to fight for him was a win-win for Saddam- it put numbers on his side, but if they died, that was also victory, since freethinkers were of no use to the Ba’ath regime. Bruder says Rashid began writing every day, poetry that documented all that he witnessed. But, “His black and white drawings of horror were laced with poems which were abstract lines to everyone but him. Ali had come up with his own secret code, protecting him from the authorities' continuous spot checks and searches…” This was an ingenious way of passing time, preserving history, and avoiding torture and death after controls and checkpoints. “He was now able to tell the authorities that the funny writing was just abstract creative technique, nothing else. In actuality, though, they represented his outcries of pain having to fight a cruel war…” Ultimately, Rashid moved to the west, to the Netherlands, into safety and freedom, where he continues to create his spellbinding art. While I look through, appreciate, and forget an endless parade of paintings, Rashid’s stay with me and I return to them again and again. I don’t feel the need to decipher them in any conscious way, and I don’t think we are meant to. The mark makings do feel like the walls of caves, whose textures are inscribed with ancient invocations from across millennia. They are transformed, however, by pure modernism, invoking and alluding to history but remaining a creative and spiritual invention of the present. So many artists, myself included, find their practice essential to their survival. We often say, “I do it because I have to.” Perhaps Rashid’s work embodies this concept more literally than we will ever experience ourselves. As such, his intriguing abstract art is not just symbolic of redemption, but a record of it. Lorette C. Luzajic This essay is from Lorette C. Luzajic's Truck, a collection of art writings, and will also be included in artist Ali Rashid's forthcoming book. something else unless means for emese they said not all who wander are lost, but i'm lost, and you're lost. the sidewalk cracks, the moths at the lamps, and the scraps of old showposter buried in the phonepole, and if i never did say i love you, i just forgot which one of us i was. maybe we could make a bonfire tonight, watch the shapes of our problems twist like tv channels in the smoke. i could meet you somewhere, i mean, i could meet you if you're not here now. that firepit we found under the trestle with claystone slabs pushed all together, cupping the heat til the edges glow like sleepy incense cones. the way you dropped empty cans in the embers and they curled like onionskin, golds and rusty blues dispersing to chalk mandalas through the ash, and TEXACO carved in the slabside like a cat's halfdisintegrated bones. or that firepit in the abandoned fieldlot with a rotted backhoe tilted half into the earth, the way crumpled papers never catch, there's so much dew, so you just sit there in your trampled wheat, sit round a broken-banded headlamp while ufo ghosts flick at the horizon like dusty ocarina notes. it's the way old shroom trips remember themselves inside your blood, in the negative space between your nerves. just here. where the mist touches your skin. it’s sitting lost with the tall ferns curling away from their colours in the dark, and the way i wish we were real. and that firepit sawn from a old iron drum in centennial square parkade. the way you roast smokies on a radio antenna, the red sirens tooling up the parkade ramp never get any closer. and stickdrawings ochered on the concrete wall, older fires remembered. flipped cars, burning stopsigns and chainlink, backpacks that walk on raccoon feet, kids with knotted twine for eyes, and that one word UNLESS, like a joke. and you just look over your shoulder, every car window's blown out, everywhere, and flowers of rye soughing from the rusty frames. right? if you'd just look over your shoulder, if we’d find the creekbank again. downstream from two green deckchairs bikelocked on an oak, that firepit, toss campingfuel and pallets off the bridge. the way you’ve got to dig out last time's ashes, plant a sixpack upside down for the kids under the creekbank who patch their jeans with fishingline and bags, we’d find the old six sideways, full of mud. and did we even meet each other anywhere? how you'd always turn from the fire, pretend to warm your skinny hands on the sky. you'd turn from the distant campflames starring the flat concrete dark, the latticed charcoal planks, like someone’s ribs left behind. i forget, and i heard you just keep turning left in a maze. walk forward, follow the wall with one hand, go left every turn. it won’t matter how you're lost. unless there's no walls in the way, or we're both going, unless i said meet me somewhere. Noah Wareness Noah Wareness makes fiction and poetry by hand with scratchy black pens. He does a lot of live storytelling at DIY shows, but Meatheads is his first novel. It first circulated in the folk punk and speculative fiction communities as a handmade zine with wheatpasted cardboard covers and speaker wire for binding. He went to school for writing on the west coast, and now he lives in Toronto with some friends. Selected Isolation

(after Alex Colville) The figures for all their bold intent amble out of the hand onto a brave and patient page: all that love's indignant dance compressed to two dimensions. The rhythm of a possible human here stripped to elementals on the edge of outgoing breath. The plastic arrangement of surface is what it seems. Enough to be informed as a particular choice of magic. Of even light a delicate compromise. Penn Kemp An earlier version of this poem appears in Penn Kemp's chapbook, EIDOLONS, White Pine Press. London ON performance poet, activist and playwright Penn Kemp is the 40th Life Member of the League of Canadian Poets and their 2015 Spoken Word Artist of the Year. As Writer-in-Residence for Western University, her project was the DVD, Luminous Entrance: a Sound Opera for Climate Change Action, Pendas Productions. Her latest works are two anthologies for the Feminist Caucus Archives of the League of Canadian Poets and the Guild of Canadian Playwrights, to be launched at the Writers’ Summit at Harbourfront in June. Forthcoming is a new collection of poetry, Barbaric Cultural Practice and a play, The Triumph of Teresa Harris. www.mytown.ca/pennkemp Edward Hopper and J.M.W. Turner: Two Old Men and the Sea

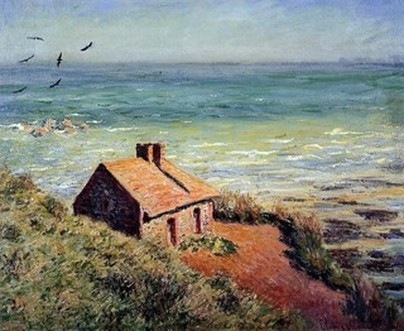

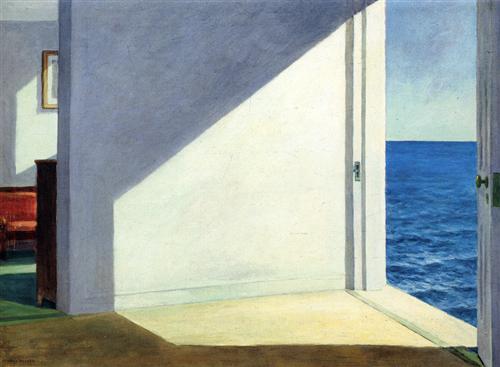

Two paintings of the sea by two artists. Looking at each as if we knew nothing of their creators, something of their respective dispositions is obvious right away. J.M.W. Turner's work is wild and stormy; you know he’s eccentric and passionate. Edward Hopper’s is detached and moody, angular rather than organic, with a sardonic undercurrent you can’t quite put your finger on. The Snow Storm’s story is well known. It’s one of the most famous works by one of the most famous artists in history. Around 1842, J.M.W. was caught in a storm aboard the ship the Ariel. He allegedly asked to be tied to the mast to authentically experience man against the gods, or at the very least, man against the gales. This might be romanticizing the Romantic painting. Without proof of the incident, there are two teams: one that upholds the anecdote as truth, and one that dismisses it as myth. I would cast my lots with Team A. It fits with the tempestuous temperament of Turner, but more importantly, it’s the exact story the painting itself tells. It’s a jewel among a multitude of masterpieces, and perhaps the wildness that sets it apart is the experiential. That artists are Method Actors is no surprise- we have a strange habit of stepping into all manner of harrowing scenarios in search of the story. Now Hopper had a mean streak and violent temper that reared its ugly head in his relationship with his wife, but he was generally a more reticent character with rather staid emotions. His work is more introspective, more thoughtful. You’d be hard-pressed to find a Hopper painting that shows his hotheaded side. His art shows disconnection and resignation, and often melancholy, but not rage. This particular painting from 1951 is not one of his famous works, and it’s not even one of his best. It’s as banal a picture of the sea as there ever was. Except, it’s not. If some of Hopper’s paintings seem vaguely haunted, this one’s ghosts are palpable. Hopper gave Rooms by the Sea an alternate title in his notes- The Jumping Off Place. After discovering this darkly irreverent tidbit, a thin, icy breeze creeps into the frame. These are only two of a trillion acts of creativity inspired by the ocean, but both are worthy of contemplation. In Turner’s, we are there at the mast, with the cold waves whipping our faces into raw meat. We are the crossroads of the elements, captive to our fate in between life and death. In Hopper’s surreal sunny calm, we’re already gone. Lorette C. Luzajic Founder of The Ekphrastic Review, Lorette C. Luzajic is a mixed media artist working in collage, paint, poetry, and photography. Visit her at www.mixedupmedia.ca. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|