|

Reading through posts in The Ekphrastic Review archives for this week, I was amazed by the variety of art, writing and writers. Within all that abundance, this month I was most drawn to these photographs and their stories. They remind me of long road trips far from home when the radio became static and the changing landscape puts distance between you and your troubles. This week’s Flashback Thursday posts promise us the possibility of reaching another place, once upon a time, in a land far, far away. ** Desert Ruin, by Neil Creighton The power of nature in the desert landscape of South Australia where “the distant mirage shimmers…” https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic/desert-ruin-by-neil-creighton ** One Viewer’s Response to Todd Klassy’s 4 Round Bales, by Bill Waters Waters reimagines the blue of Todd Klassy’s photo in the far-flung countryside. https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic/one-viewers-response-to-todd-klassys-4-round-bales-by-bill-waters ** The Photography of Robert Cadloff (bomobob) Let’s get off the interstate, put the top down, and cruise two-lane highways “looking for remnants of a time when style was so much a part of signage” in this interview with photographer Robert Cadloff. https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic/the-photography-of-robert-cadloff-bomobob ** Space Station Crew Sees Lots of Clouds, by Marc Alan Di Martino High in the ether “…frosted tufts of clouds make you want to poke your finger in and lick it…” https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic/space-station-crew-sees-lots-of-clouds-by-marc-alan-di-martino There are almost seven years worth of writing at The Ekphrastic Review. With daily or more posts of poetry, fiction, and prose for most of that history, we have a wealth of talent to show off. We encourage readers to explore our archives by month and year in the sidebar. Click on a random selection and read through our history.

Our occasional Throwback Thursday feature highlights writing from our past, chosen on purpose or chosen randomly. We are grateful that moving forward, Marjorie Robertson wants to share some favourites with us on a regular basis, monthly. With her help, you'll get the chance to discover past contributors, work you missed, or responses to older ekphrastic challenges. Would you like to be a guest editor for a Throwback Thursday? Pick 10 or so favourite or random posts from the archives of The Ekphrastic Review. Use the format you see above: title, name of author, a sentence or two about your choice, or a pull quote line from the poem and story, and the link. Include a bio and if you wish, a note to readers about the Review, your relationship to the journal, ekphrastic writing in general, or any other relevant subject. Put THROWBACK THURSDAYS in the subject line and send to [email protected]. Let's have some fun with this- along with your picks, send a vintage photo of yourself too!

0 Comments

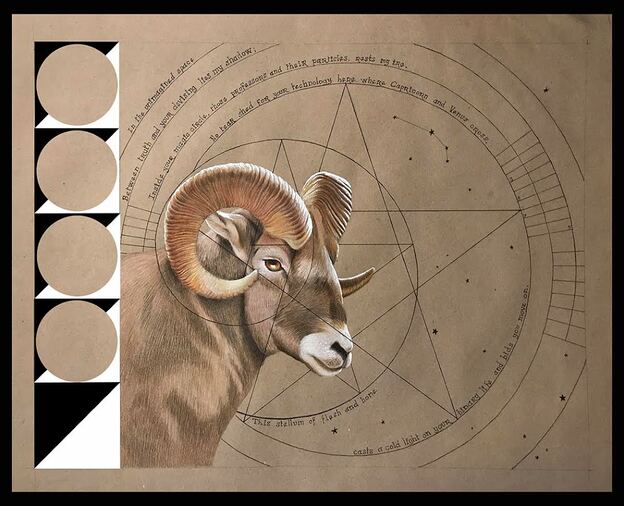

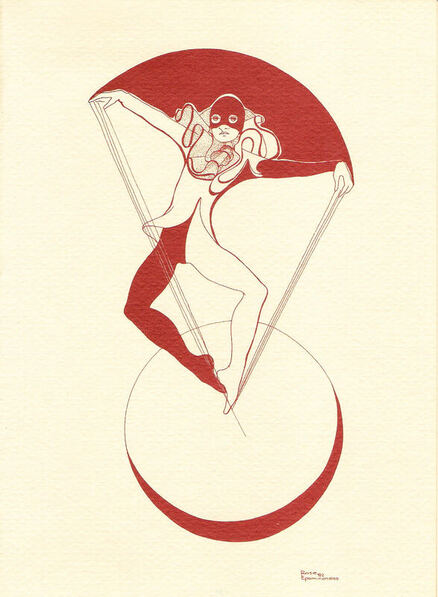

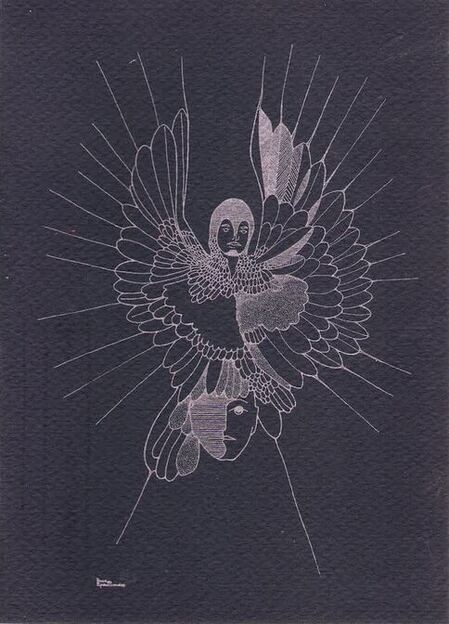

Aries Rising In the unimagined space between truth and your devising lies my shadow; Inside your magic circle, those professors and their particles, rests my ire. No tear shed for your technology here where Capricorn and Venus cross. This stellum of flesh and bone casts a cold light on your binary life and bids you move on. J.W.Wood J.W.Wood and Cyrille Saura are currently collaborating on a series of texts and images, the first of which is being offered to you for publication and has already been exhibited at The Hearth Gallery on Bowen Island, BC. Cyrille is a trained architect and professional illustrator who has authored two commercially-published books in her native Switzerland. For more about J.W.Wood, please visit www.jwwoodwriter.net yin and yang Joyful equilibrium Connect to your power Move the world She, them, their and his Dance power Balance life forces Use the might of a spider yarn Rose Mary Boehm Rose Mary Boehm is a German-born British national living and writing in Lima, Peru. Her poetry has been published widely in mostly US poetry reviews (online and print). She was twice nominated for a Pushcart. Her fifth poetry collection, DO OCEANS HAVE UNDERWATER BORDERS, has just been snapped up by Kelsay Books for publication May/June 2022. Two further manuscripts are ready to find a publisher. https://www.rose-mary-boehm-poet.com/ This editorial tell-all will help you make sense of what goes on behind the scenes, the slush piles, the wait times, the best bets and more. Inside advice on best practices and what you can do to up the odds of getting accepted. We will look at sample submission packages, yay and nay cover letters, breaking down guidelines, the 100 submission or other submission challenges circling around writer's groups, reasons for rejections, and what's up with industry reading fees.

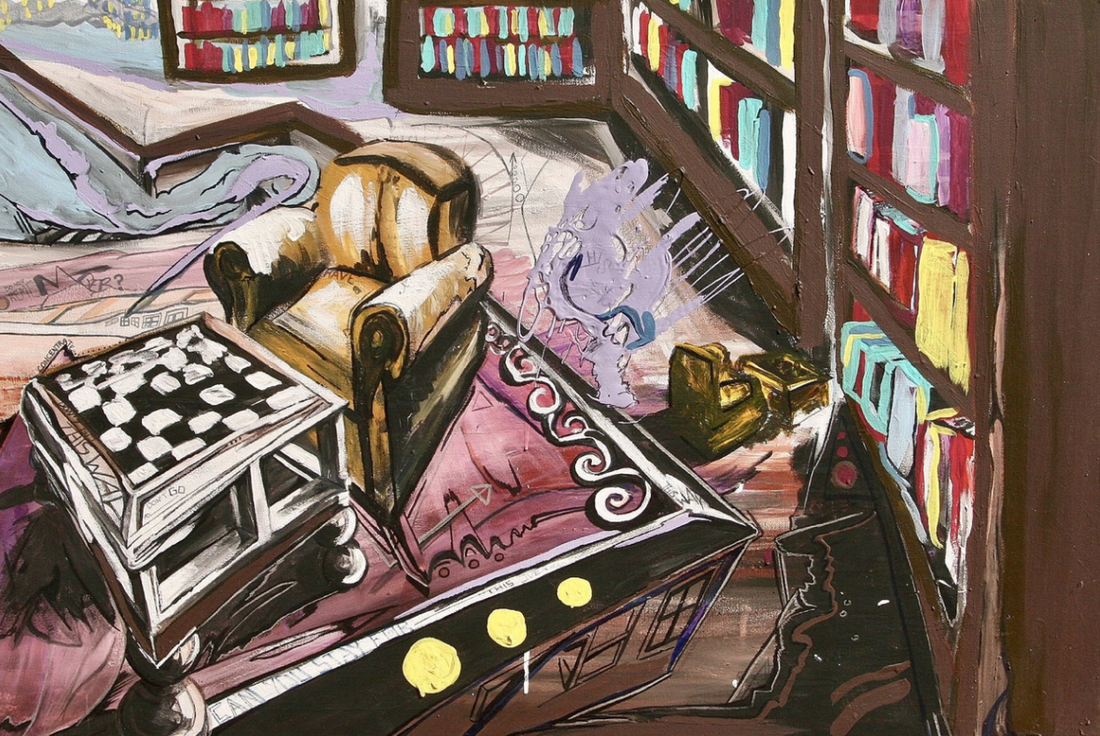

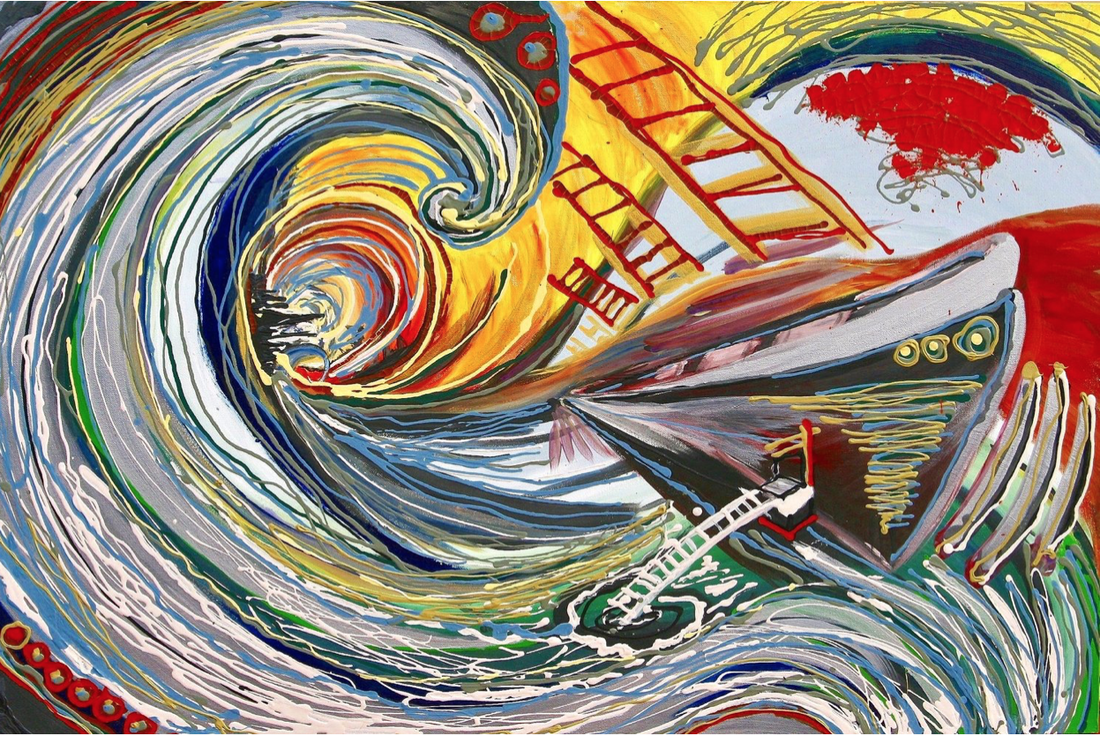

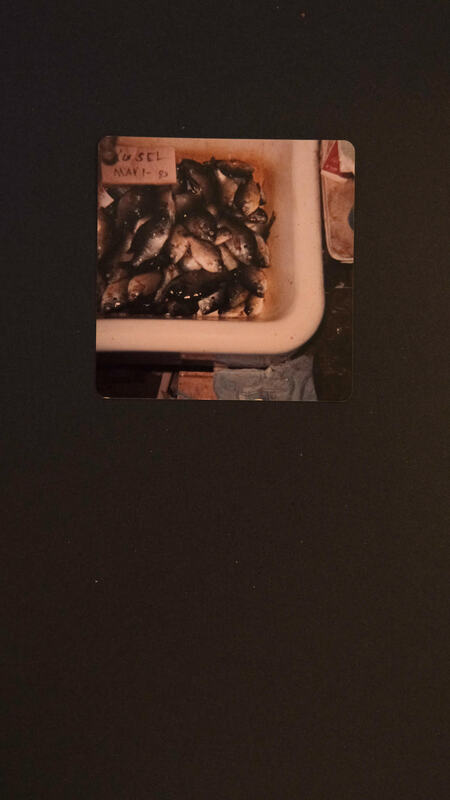

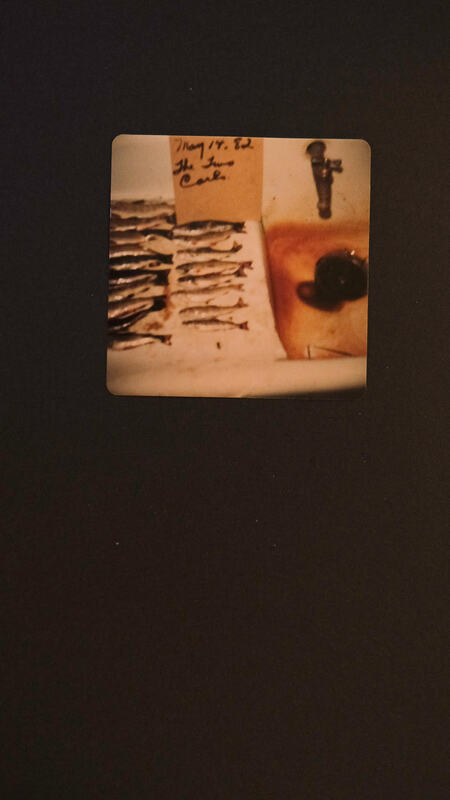

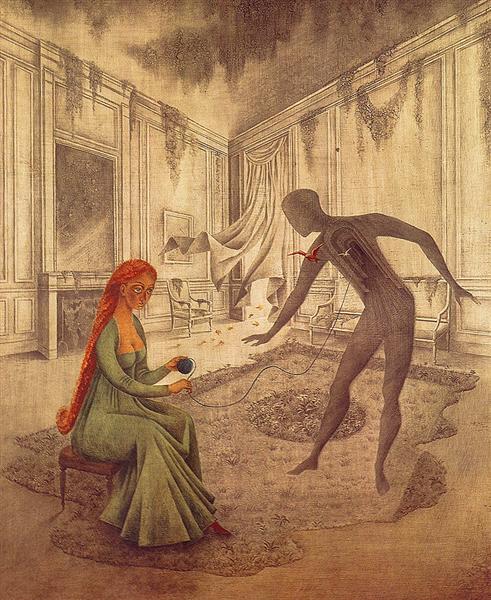

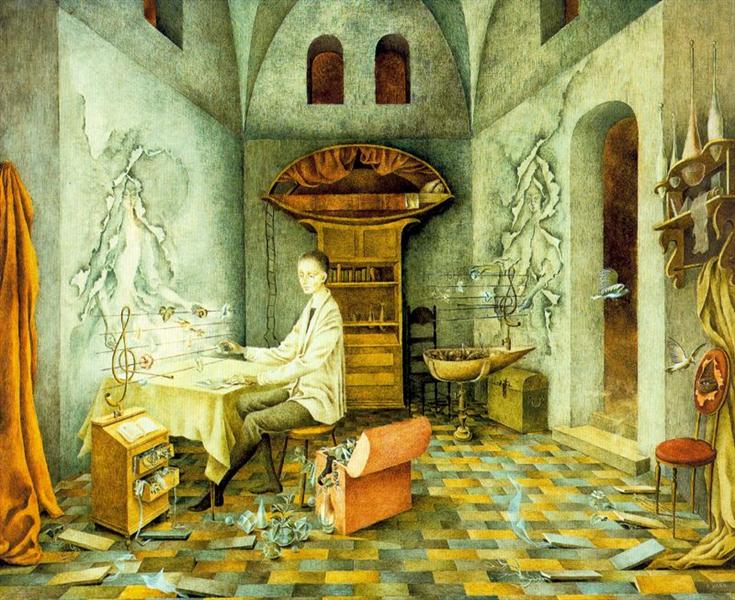

Click here to shop this and other upcoming workshops, or click on the image above. Broken Faith The depths of Tartarus can’t compare to the endless and unholy darkness that swirls across the canvas. The evils that lurk in Pandora’s hellish box could hardly hold a candle to the horrors found here. Mortals weep in shock and horror, their feeble minds broken by the images of destruction they are shown. Broken faith, like the bonds shattered between Jason and Medea. Trickery and lies, like those declared by Odysseus so that “nobody” could maim poor Polyphemus. Abandonment, as Aeneas abandoned Dido to wallow in despair until her last breath. But it is not all destruction, and it is not all fear. Ares gazes in awe at the battlefield, the bloody reds and soulless greys smeared for all to see. Artemis gasps in delight as she glimpses the moons on the page, clearly a tribute to her. The writhing mass of colours and shapes a pentimento of the betrayals that named it. There was beauty in destruction, and rebirth in betrayal. Reclaiming the happiness stolen by the hurt restores the faith that had been broken. Breanna Hanley Breanna Hanley is an English major with a concentration in writing and a minor in Women and Gender Studies at Lock Haven University of Pennsylvania, USA. She plans on graduating in May of 2022. She currently resides in the small town of Beech Creek, Pennsylvania. In her spare time — outside of writing — she enjoys crocheting and playing video games with her friends. She hopes to one day have a job doing editorial work for a publishing company and write her own novel. Sun on South Street The sun was everywhere, once, drenching each corner with incandescence, pooling around fat cats as they lie, kissing the face of a woman to wake her in the early, white dawn. There were years of ever-sunlight on South Street; this world content to glow, to grow sunflowers in sidewalk cracks, to dance in beams across the floor. A woman waltzed in the sun on South Street, once. Her bare feet swung in sweet tandem with each fractal of light, flitting over the floor’s worn boards. The sun peers, now, through cracks in the haphazard handiwork, sometimes glinting off nails left jutting out into the South Street darkness. The boards pried from the floor, pinned to the window pane, pitiful in their effort to forget what once shone here, who once danced in light. Every sun-spot long faded, only golden memory remains, wandering lonely halls, enveloped in cutting wool, left to decay with South Street’s pain. Olivia Hanna Olivia Hanna is a Social Work major at Lock Haven University of Pennsylvania, USA. She plans on graduating in May of 2024. In her spare time she enjoys playing music and making art. The Choice Late night, mid-morning, dawn, the door of the library clicks open, cracks wide to rooms of elsewhere & beyond—imagination’s Open-Sésame to other doors, libraries, landscapes. Click open possibility. What book shall we pull from the shelves? Beyond Open-Sésames, imagination’s magic enters the mind’s inner workings, gathers possibilities. What book shall we pull from the shelves? What ancient treasure tug from the tale? The mind’s inner workings enter in, gather tools of chessboard and floor, bookcase stacked with tale and treasure, the ancient why of creation sparking each synapse of stacked choice: chess, ceiling, floor, books—tools to chisel word and image onto the shaped space of creation. Sparking each synapse, the mind reaches beyond reason to memory, chisels word and image onto the shaped spaces of now, before, maybe, if—choice the reason the mind reaches beyond memory, mirroring the large and small. This way. Choose now, before, maybe, if— or not. Your turn. Concentrate. Mirror the large and small. This way. Do you remember? Can you stay? Yes? No? Your turn. Concentrate. What move in chess shall we open with? Do you remember? Can you stay? What voice is woven in the fabric? What move in chess shall we open with? Follow the arrows to pawn or king. What voice is woven in the fabric? Here is the story of Open-Sésame. Follow the arrows to pawn or king, rooftop or floorboards. Don’t go without a story. Open-Sésame your way to elsewhere & beyond. Climb rooftops. Sketch floorboards. Go. What path shall we take today through this library? This way to elsewhere & beyond. A splatter is not a mistake, but a choice. What path shall we take today through this library? Follow the inner workings of the mind. A splatter is a choice, not a mistake. Cracks open the room to elsewhere. Always the inner workings of the mind follow choice. Each dawn, mid-morning, night, crack open rooms to elsewhere. You hold the pen and paintbrush. Late-night, mid-morning, or dawn, choose imagination. Click open the door to the library. Marjorie Maddox *Used by permission of the artist. Italicized phrases are taken from the artist’s description of the work, as well as from words and phrases hidden within the painting. Ark Ladders to below/above to turn off the faucet to weeping to turn on the spigot to here/now to unleash the liquid to water to weary to whiplash to swirl in the iris of horizon to witness the wet of windswept to hide in the eye of reject to float in the drowning of hopeless to breathe in the rattling of broken to gasp with the mouth of ocean to curl with the swish of sudden to gulp with the whir of twisters to swallow with the salt of senseless to blur with the vision of serpents to spew with the sputum of whales to reek with the regurgitation of Jonah to sink in the rise of remorse to know with the blind-eye of Noah to soar on the dry-sky with dove to circle the submersion of world to flutter and hover to dive and discover to finally land. Marjorie Maddox Noise My own electrical storm break- dancing the sky of skull, riotous riffs on the unpredictable. Even before the EEG MC’d asymmetrical jerks, my tolerance for sound’s tossed out with each dizzying jag of note. Each ragged twirl, each syncopation on steroids, batters the cerebral, cyclone gone haywire into some vast static of seizure. Richter scale of cacophony— tornado and earthquake, firework and fissure— this ramped-up Chaos axes the faux door, pummels the thin walls, evicts balance from the brain. No predictable melodic drone sliding forward toward home, no Quiet Sweet Quiet easing the night into calm. Marjorie Maddox Professor of English at Lock Haven University, Marjorie Maddox has published 13 collections of poetry—including Transplant, Transport, Transubstantiation, about her father’s unsuccessful heart transplant; Begin with a Question (Paraclete 2022) and the ekphrastic collaboration with Karen Elias Heart Speaks, Is Spoken For (Shanti Arts 2022)—the story collection What She Was Saying (Fomite); four children’s/YA books; and Common Wealth: Contemporary Poets on Pennsylvania(co-editor). Her forthcoming collection, In the Museum of My Daughter’s Mind, an ekphrastic collection based on 17 paintings by Anna Lee Hafer (www.hafer.work ) and including work by artists Margaret Munz-Losch, Antar Mikosz, Ingo Swann, Karen Elias, Greg Mort, and Christian Twamley), is forthcoming (Shanti Arts 2023). Please see www.marjoriemaddox.com Anna Lee Hafer is a studio artist based in the Philadelphia area whose work is heavily influenced by famous surrealist painters such as Rene Magritte, Salvador Dali, and Pablo Picasso, all of whom strove to create their own realities. these works are small glimpses into a particularly confusing, but utterly unique worldview that entirely dictates and follows its own specific set of rules. Anna Lee Hafer graduated from Roberts Wesleyan College in Rochester, NY in 2019 with a Bachelor of Science in Fine Art. She relocated to the Philadelphia area to pursue a career in studio art. Previous experience in the art field includes: studio exhibitions at Davison art gallery and Rochester contemporary art center in Rochester, NY, as well as publications in Still Point Arts Quarterly. Please see www.hafer.work At Least 18 Photos of Fish After another day of fishing at the house on Gilbert Lake, (the one in Wild Rose, not the one in West Bend) Carl returns to the cabin with his small red cooler As he comes into the house, Norma smells him— not sweat but the slick wet smell of fresh fish He retrieves the camera, its one glassy eye open to capturing the abundance in sepia to offset the bluish fluorescent light, from the pantry and sets it on the counter next to the heavy cooler, which he opens Carl removes the empty milk carton (makes you big and strong, so that you don’t wear out catching fish after fish, except it sloshed in his stomach as he stepped out of the boat and walked uneven up to the cabin) This is 1983. There are maybe 27 fish Then, he overturns the cooler into the porcelain sink the fish jump for the last time like skipping stones, sick green body pearls slipping iridescent into the basin with oily, sludgy melted ice which drains beneath them Eyes kissing eyes glassy cataract stares of a pescatarian slaughter Carl checks how many shots are left on the roll of film Good— there’s enough Using a fresh black sharpie Norma has prepared the placard for him to prop on top of the smooth sheening keratin sharp fins cutting at one another His visitor’s name, not his Russel has finished mooring the boat, has already removed his coveralls, and has already gone to shower The denim hangs over the lip of the the hamper under the sink The room is quiet the fish suffocated hours ago Norma can’t prepare dinner until the filets are cut but the bowls of flour and egg wash are already on the counter, waiting He feels starved. Carl turns on the flash and takes two pictures just in case — last year, some of the film had corroded and he lost count of June’s catches This is 1985. There are maybe 50 fish They almost overflow the sink this time President Reagan has been reelected Carl puts the camera away and takes out the filet knife He scales it first then guts the cold fish their white muscle sliced to drop red, glinting organs into the barrel Ever since he sold the farm in West Bend and moved to Wild Rose this has stopped feeling like a chore what a freedom this is to catch fish, to beat the lake (and this average he calculated himself) 113.75 fish each year what a freedom, indeed P. D. Edgar P.D. grew up between central Florida and Managua, Nicaragua. His poetry exists at the crossroads of identity and spirituality on the landscape of media and the environment. He currently pursues masters' in Journalism and Media Studies and Creative Writing at the University of Alabama, and hopes to one day found a community bookstore. He may be found online @PDEdgar30. Or How Could He Ever Win The Heart of Any Woman? She shuffled seasons at will, carpeted her floors with grass and wildflowers, picked the first man who showed her a spark of kindness and carved his heart in her own image. Words danced in vibrant hues over the pages of her diary, giving life to a silhouette hovering in half tones in midst of the grisaille. With an empty stare, she’d sit for hours, see his shadow kneel in front of her, listen to his fading merman’s song. She’d redress his crossed eyes, bent shoulders and slight limp, or else, how could he ever win the heart of any woman? She thought of Beauty and the Beast, although he was no beast and she was no beauty. Until the day she flung windows wide open, let gusts invade the rooms, let her skin bear the colors of dead leaves, and knew time had come to pull the thread, unravel the feelings spun around his heart. Hedy Habra This poem was first published at Gargoyle. Or Did You Ever Wonder What It’s Like To Have Hot Flashes? Imagine a nebulous landscape covered with budding volcanoes See yourself emerge from one of its peaks head heavy with slumber Gasping in the rarefied air you enter a liminal space where unlucky few Forever trapped past conception are condemned to parthenogenesis See yourself emerge from one of its peaks head heavy with slumber Think of your skin as a primed canvas permeable to imprints Forever trapped past conception, condemned to parthenogenesis See how the change of seasons leaves indelible marks all over your body Think of your skin as a primed canvas, permeable to imprints, You yearn for the sight of a veil billowing on a deserted deck’s caravel See how the change of seasons leaves indelible marks all over your body Like the sfumato created by the passage of a candle over moist paper or canvas You yearn for the sight of a veil billowing on a deserted deck’s caravel Suddenly a cooling current lassoes drifts unfurling into ashen flames Like the sfumato created by the passage of a candle over moist paper or canvas Or a haze hiding a palimpsest of thoughts carried by windswept fumes Hedy Habra This poem was first published by Rusted Radishes.  Harmony, by Remedios Varo (Mexico, b. Spain) 1956 Harmony, by Remedios Varo (Mexico, b. Spain) 1956 Or Call Me a Hoarder if You Will but Try to Understand

Each and every object in my drawers has a story of its own. When I revisit the selves I once was, minute black silhouettes Align themselves over the power lines of my mind as on a score Until the outline of an alter ego irrupts, adding a silent note. When I revisit the selves I once was, minute black silhouettes Rub over every object's skin absorbing smells and vibrations Until the outline of an alter ego irrupts, adding a silent note And would they engage in a dialogue in the utmost darkness? Rub over every object's skin absorbing smells and vibrations Like the rosary stringed with pearls my mom loved so much And would they engage in a dialogue in the utmost darkness Map the vestibules of memory, run fingers over shining veins? Like the rosary stringed with pearls my mom loved so much Boxes of left-over yarn, her crocheted creations tucked into drawers Map the vestibules of memory, run fingers over shining veins Call it a bric-a-brac fit for those of us prone to engage in bricolage. Boxes of left-over yarn, her crocheted creations tucked into drawers A bleached sand dollar that might become your grandson's treasure. Call it a bric-a-brac fit for those of us prone to engage in bricolage. Nothing is what it seems, only the meaning invested in its arcane language A bleached sand dollar that might become your grandson's treasure And just the sight of a handwriting triggers the deepest emotions Nothing is what it seems, only the meaning invested in its arcane language. I keep digging as I become the archeologist of my own experience Hedy Habra This poem was first published by MacQueen's Quinterly. Hedy Habra is a poet, artist and essayist. She is the author of three poetry collections from Press 53, most recently, The Taste of the Earth (2019), Winner of the Silver Nautilus Book Award and Honorable Mention for the Eric Hoffer Book Award; Tea in Heliopolis Winner of the Best Book Award and Under Brushstrokes, which was a Finalist for the Best Book Award and the International Book Award. Her story collection, Flying Carpets, won the Arab American Book Award’s Honorable Mention and was Finalist for the Eric Hoffer Award. A seventeen-time nominee for the Pushcart Prize and Best of the net, and recipient of the Nazim Hikmet Award, her multilingual work appears in numerous journals and anthologies. https://www.hedyhabra.com/ Orange and Yellow Drinking a therapeutic concoction of herbs wasn’t the worst part of the healing tea treatment. Gerald’s mother-in-law, Sonia Bonnefoi, had warned him about the taste. “It’s bitter,” she said. “That’s how you know it’s medicine.” It was the night-long purge that broke his spirit and left him burning as though shedding his skin from the inside out. After the sweating and shivering had stopped, he entered dream sleep. He was a young man, again, walking the empty downtown streets of his hometown alone. Colours came vividly, each with a meaning and a voice like shouting or whispering. White was the inside of his church, countless Sundays spent looking at the ceiling of white plaster and thousands of cracks intertwined like spider webs. Where one ended, the next picked up the thread, never broken, and he was as small as a seed at the source of the sprayed lines overhead. Black was a heavy canvas overhang of the drugstore where his girlfriend first touched his hand and shared his ice cream soda, the memory of cold sweetness on his lips like an antidote to the bitter therapy. Yellow was aggressive and blinding, the childhood home he painted one summer with his father, oddly bright like Van Gogh’s house in Arles where the artist’s earlobe was cut off. Blue was the ice pond in Maine where he skated as a boy, powdered snow misting his face, his heart pounding because while dreaming he knew those times were over. He would never again feel as he did then. The realization was enough to bring him back to the dark, still room. He turned over and vomited into a bucket beside the bed. He wanted to walk through the colours some more when his wife, Helen, came in to rub his back and press a cool cloth to his forehead. She whispered all the things they could return to doing when he recovered—shopping for antiques, having champagne brunches with other couples.The expectation of his crawling back to the artistic circle he’d once ruled over made him turn over on his side and push her hand away. He understood her attempt at encouragement but in his suffering, he wondered why couldn’t she let him be? In the dark, he blamed her. If she hadn’t pushed him to be better, he could carry on in his new sham life as the elite neighbourhood vagabond with the signature white hat who sips wine in cafés. Couldn’t she see this was all he was—a tired, confused, old man no one cared about? He woke, again, when the cat jumped on his bed and stretched across his legs. Sonia entered the room and threw open the curtains. The glare of morning filled the window frame with orange and yellow. She went over to the bucket and looked at its contents. “Looks like you have a heart problem, too. You’ll need to get that checked,” she said. Those first words after a long night normally would’ve angered him if he’d had the energy. In the only protest he could muster, he sat up too quickly and saw the room spin. Her gentle touch on his shoulder calmed him. “I can see you don’t care for me right now. Just remember, now your body can heal. Did you see what you were looking for?” He hesitated. “Maybe I did. I don’t know.” “When you know, you will be cured of this ailment,” she said and limped away while massaging her bad hip. At night, as he went through the cleansing, a thunderstorm had rumbled and crackled outside, but now the sunshine was bright, and birds sang as they perched among new blossoms. After dressing, he went downstairs to the kitchen. Fresh air entered softly through the open window. The coffee had already been made. The black cat slept curled on a chair. Sonia read the newspaper, her face hidden. The headlines were about bad news in other places but add one small misstep and a headline could’ve been about him. Instead, another man was having the bad day that could’ve been his, perhaps should’ve been his. Gerald fixed a plate of eggs and toast. “I can overcome this on my own. I don’t need any more help,” he muttered fiercely to himself. Sonia spoke from behind a leaf of newspaper. “Who knows the right thing? Thinkin’ about it and tryin’ to change, that’s a misperception there. You don’t change with your head. You do it with doing. It’s a mistake to try to put a righteous action over a tainted one. You must take the old covering off first. The good one won’t go on over. It just fits, and you can’t get it on over anything. Take the old off, I say.” “I’m not a religious man.” “Religion?” she said, looking over a leaf of paper. “It’s called having fortitude and common sense!” Helen came in and touched his back as she went by. “You should drink a lot of water today and no caffeine. Do you want me to run you a bath?” Sonia scowled at her daughter. “He’s not a child.” To Gerald she said, “You’re not a child. You’re a 60-year-old man. Listen to me. I’ve heard all about your eye trouble, your hallucinations or what have you. Your eyes are speaking to you, and now that they have your attention, you need to spend some time understanding what they say instead of spending all day on the street like a hobo. My Helen should not be wandering the streets at night looking for you. Your eyes cannot speak English or French, so don’t use your head.” She scanned the kitchen. “I got something to see to. Bébé, go get my purse in the hallway, would you?” When Helen returned with the purse, Sonia rummaged through it for pen and paper and scribbled a name and address. “Murphy’s Drugstore in New Orleans. They have remedies for every manner of ailment, I guarantee it. Don’t stare at me with bug eyes. I know you know it’s a hoodoo shop. Every problem you can imagine goes in their door. You tell Miss Geneviève you’ve taken my medicine already. You can go while you’re there for your art thing today. Get it done! No point in being idle now.” After a short while on the highway, Gerald and Helen approached New Orleans. Helen instructed him, “Don’t tell the employees about your problems. At these hoodoo shops, they put spells on customers to get them to spend money. If that doesn’t work, they try to upsell. You tell them your problem, and they say you need ten things to fix it.” “I haven’t made up my mind about going.” She laughed in a forced way. “I thought that’s what all this was for. I thought that’s why we went to see my mother. You know her way of treating health problems.” “What would people say if they knew I’d resorted to using folk medicine?” “No one will know unless we tell them, Gerry.” He tried to bring some levity into the conversation. “I feel better. Maybe Sonia’s strange concoction has cured me,” he said. “Why don’t you come with me to the fundraiser? You might see some people you know.” He glanced at her to see if she had a reaction. Her face was calm. She said, “You should follow through with the drugstore and be done with it. It won’t hurt you to go and it could help. Be polite, be friendly, but know your boundaries. Talk only to Miss Geneviève.” Quietly, he said, “It occurred to me I could bear it if you went to the fundraiser with me.” She looked at him and raised her eyebrows. “You know I never go to the charity art auction events anymore.” “I’m having lunch with Marcus afterward. Come with me,” he said and instantly regretted it. “You said I’d only be bored. You told me it was a distraction with me there.” “I know, I just thought…” “Oh, Gerry, you really want me to come?” She looked expectant like the young woman he met years ago. Only now it was as though she’d been waiting for the real him, not this changed him, to show his face, but he didn’t know who that was anymore. “You’re probably right. Not exactly your scene, as you said. Maybe it’s best if you see your friends and I go to this thing and have lunch with Marcus.” He glanced at her. Her head turned away to face the window. “We can visit our favourite spots afterward and go to dinner,” he said. “Fine, fine,” she replied. After a few minutes, she said, “I want you to be well. That’s all I want.” She held her gaze on him now. “Would you do that for me?” He told her he would. While Helen visited friends, Gerald went to the art auction fundraiser and had lunch afterward with two men. Jim was a wealthy donor from Florida who had recently begun purchasing art to reflect his sudden dramatic wealth from cell phone grips that attach to just about anything. The other, his friend Marcus, was a painter. Since Gerald’s art critiquing had ended abruptly with his eye trouble, he’d become a consultant to wealthy clients, making art deals on commission. They may as well have hired someone younger and hungrier, who’d hustle and pretend to like people, but Gerald needed a good piece to sustain his reputation, and such things still mattered to him. “The auctioneer was good,” Jim said as they sat at a table outdoors. “He should be. He prepped for hours,” Marcus replied. Gerald’s interest in talking shop had drained away. He tried to change the subject. “I haven’t been here in some time. You can see the work they’ve been doing on the river, redirecting it,” he said. Marcus shook his head. “I’ll never understand why they think they can do a better job making a river than Mother Nature herself. It’s a kind of institutional arrogance. The river will have its way. We know that. We live with the risk.” “They have to find a solution,” said Gerald. “There is none except for the next disaster,” Marcus added. “They think we don’t know what they’re doing and we’re a bunch of dummies, but they’re hiding in plain view, like politicians and their donors.” The server came and asked to take their order. “I’ll have the chicken and a green salad,” said Jim. The server said they had an arugula salad. Would that do? “Surely, and a Dr. Pepper and some crackers to go with that salad.” “I’ll try the pasta with pesto sauce. Let’s have a bottle of Pinot Noir, too,” said Marcus. “The same,” Gerald said. The server nodded his approval, collected the menus, and went away. When he came back, he brought a glass of soda and a bottle of wine, popping the cork and filling two glasses. Jim lifted his soda, saying in his toast, “Two things you can’t get in Florida—jalapeños and Dr. Pepper. Cheers.” “That’s fascinating,” said Gerald and raised his glass before downing half the glass. New Orleans brought out the fighter in him, the one who owned his life instead of timidly wondering whether or not the pieces of his life would come back. Jim said, “Plenty of things you can get anywhere—hookers, for instance. Not that I ever tried. You can’t tell them from anyone else. Maybe you meet someone at a bar, but you’ll never know if she’s a hooker, a college girl, or a cop until it’s too late. Used to be you could tell. Not that I would know.” “You’re crazy,” Marcus said. “I’m a by-the-book kind of fellow now,” Jim said. Their meals arrived. When Jim’s chicken and salad came, he took a bite, winced, and dropped the fork. “I didn’t come all this way to eat hamster food. Hell, pass me the bread and butter,” he said and tossed the ice water into a bush. “Fill up this glass with wine.” He drank. “Ah, like warm velvet.” Marcus laughed. “You know what they say: ‘All roads lead to sin.’” Jim asked, “Is that what they say?” “Sure. Know what comes next?” “You’re about to tell me.” “You ever slipped with your wife?” Marcus said. “Nope, never slipped. Been married twenty years. No point in slipping now.” Gerald was following the conversation in silence as he drank. He could feel the warmth of the alcohol in his veins, in his mind’s eye see it opening sweetly his closed spaces. The men looked at him and laughed. “Come on, Gerry!” Marcus said. “Hmm? No, of course not. Helen and I love each other very much.” In this relaxed state, he would not come out and tell the truth—Helen was unhappy. He hadn’t touched her for some time and was often foul-tempered. Some nights he got out of bed and went to the living room to sit and think. When he couldn’t reach a decision from thinking, he fretted over losing her at this late stage in the game. “It’s got nothing to do with love, you know that,” Marcus scoffed. “Helen is a lovely lady, I’d like to add.” “Marriage is a kind of tug-o’-war,” Jim said, pointing his fork at Gerald for emphasis. “You do slip, and Helen’s gonna torture you the rest of your life. Maybe even come into your bed at night and cut you.” “She would never!” Gerald said. “Did you hear about that woman who locked her husband in the bedroom after he got drunk and rough and then he got out and shot everybody with a pistol?” said Marcus. “Where was that at?” asked Jim. “Down in…you know where I mean, twenty miles from Thibodeaux. He shot the four kids and they killed themselves, the parents did,” Marcus said. “Oh, he killed the four kids?” Jim said. “That’s what they say.” “She killed herself after?” “The news said that, but I don’t know if I believe it. He probably killed her, too. She was probably the first to go. They always kill the woman first. The kids came after. He was mentally disturbed. Delusional,” Marcus said, shaking his head. “The devil whispered something in his ear, and he went over the edge.” Jim said, “I heard he came from a big family. He had friends. It doesn’t make sense. There had to be something wrong with him to crack like that. Hallucinations. Voodoo. It infected his mind.” Fear sparked in Gerald. There were those words—hallucinations, voodoo! With the turn in their conversation, his happiness—once alive in the banter of their conversation—flickered in a dark place. “That’s not right,” he said and looked at Marcus for support. Marcus said, “That’s not voodoo. That’s something else. Voodoo is a religion with gods and rituals to help you get through life. All we got around here now are shops for tourists.” “How do you know?” Jim said. “I live here, don’t I? We shouldn’t be talking about it casually in conversation at the table. It’s bad luck. Bottom line, people need to keep their business in their pocket, do their job and follow Jesus. Those poor people were unlucky,” said Marcus. Jim said, “No matter. Even if the kids survived, they’d of had nothing. I can only speculate if my parents killed themselves how I would’ve ended up. I’d be seeing doctors my whole life. Maybe become a pervert or a thief or something.” Marcus said, “I don’t understand it.” “Some people are so messed up they don’t even know what they’re doing to people.” “We all have to die,” Gerald said, “but what a terrible way to go.” Drinking steadily, he downed his glass and waved for another bottle. A wave of dizziness swept over him. He placed a glass of ice water against his head, and the spell quickly disappeared. He noticed Marcus watching him. He dreaded moments like this when he’d have to explain himself. As calmly as he could, he asked, “What is it?” Marcus said, “We’ve been friends for, how long now, about ten years? I just realized I don’t know what you’re running from.” “What?” “Every person runs. You carry it with you, this thing. Come on. Tell your old buddy your secret.” Gerald thought for a moment. He would not tell them about his marriage (because it would be inappropriate) or how he feared a descent into dementia more than death. He would not tell them about his mother-in-law’s treatment and his hallucinations followed by ecstasy (because the teasing would never end). He was a dignified man who had given in to folk remedies. He settled on the most personal without giving away too much. “A funny thing happened. One year ago, I was sitting at my desk writing and when I looked up, the room had changed, as if someone had come in and replaced the table and chairs. After that, whenever I have an episode, I stop what I’m doing and leave for a few hours until it passes,” he said. The men stopped eating and looked at him. “Have you been to a doctor?” Marcus said. “Yes, of course.” “What is it?” “Maybe dementia, maybe stress. The tests are inconclusive. My eyes are fine,” Gerald said and added reluctantly, “I’m thinking of retiring.” Jim said, “Not a bad idea. I’m ready for it myself.” He reached for the butter. “Maybe he shouldn’t,” Marcus said. “I have one Gerry’s never heard before. My friends and I got drunk at our high school homecoming and went to a palm reader as a joke. She told me if I didn’t stop drinking by the time I turned 30, I’d get sick and die within five years. I’m still here,” he said, raising his glass above his head. Gerald patted him on the back. “You’re going to die, but she got the date wrong.” Jim said, “Have you ever thought about what you want to be done after you die?” “Here we go,” said Marcus. “Let’s change the topic, gentlemen,” Gerald said. Marcus said, “That’s the wine talking. When I kick the bucket, I want to have a Hurricane on the rocks in my hand and my lady love in my arms. I want to be cremated. That way all my friends, like dear, old Gerry here, can take a handful of my ashes and spread them anywhere—in the river,” he said, gesturing over his shoulder, “in the backyard, hell, sneak me into some concrete and make me part of one of those new buildings going up over in Marigny.” “Ever the pragmatist,” Gerald said and motioned for the check. He wanted the talking to end and to lie down somewhere alone. Gerald excused himself and paid the bill before there was any argument. When they stepped outside, Marcus embraced him and told him to be well. Gerald walked unsteadily to his car and fumbled with his keys. When he got in, he promptly fell asleep and dreamed of flowing colour, and he was a boat floating on a river of cool, soft mud into a black hole. He woke when Helen called. “Are you picking me up now or later?” “I can come get you now,” he said. “Are you hung over?” “A little.” “I knew I should’ve gone with you. What did you have? Never mind, I don’t want to know. Get yourself a cup of coffee and go see Miss Geneviève, honey, and I’ll meet you at St. Augustine in the square at three-thirty. Don’t argue with me. I’ll see you soon,” she said and hung up. Gerald went back into the restaurant to get some coffee to go and drove through city neighbourhoods until arriving at Murphy’s Drugstore. A small sign indicated it was a seller of root remedies, candles, herbs, and charms for believers and non-believers alike. When he arrived, he stood on the sidewalk and looked around to be sure no one he knew saw him considering the place. The storefront was a plain building with vines of ivy on the sides and along the windows. They were respectable-looking windows. Surely nothing so horrible could come from such a place. Inside, the wood flooring was worn. The place smelled of herbs and burning candles. The interior of the store was mercifully dark and cool. In the store, three people stood in line—a man wearing a hard hat, a young woman in a dress suit, and another woman with bangles along her arms. When his turn came, he gave his name, and a woman came from behind the counter to take his hand. “I’m Miss Geneviève. Sonia Bonnefoi said to expect you. Come on in the back with me,” she said. She led him down a long aisle, reciting the contents of the shelves—bayberry candles, brown bottles of oils of narcissus and myrrh, statues of Mary, Caribbean herbs for Yoruba spells and Santeria palos from spirit trees, snakeskins, bath salts and charms. “We have candles for steady work, candles for want-a-man, candles to keep the law away and for finding a job. The most we sell are for people looking for work,” she explained. She led him into a room in the back of the store and shut the door behind her. He fiddled nervously with a toothpick in his pocket. “I don’t buy into folk medicine ordinarily. I’m only here as a last resort,” he explained. “If I had a dime for every time I heard that,” she said and motioned him to a seat. Gerald sat in a metal chair in front of a painting of Jude, patron saint of hope and impossible causes, staring directly at him, and a small table of burning candles. She sat next to him and said, “Tell me about your problems, and I’ll try to help you.” As he told her about the episodes, she nodded and frowned. She said, “Something has taken up residence in your body. I have just the thing. Hang on a minute.” She rose and went to a desk where she studied an open book, flipping tattered pages. She went over to where he sat, touched his shoulder, and moved her lips silently. Back at the desk on a folded card she wrote his prescription. “You’re to say these words out loud, recite Psalm 59, ‘Deliver me from my enemies, O God…’ and burn a ‘stay away’ candle every day until the symptoms stop.” It seemed easy. Too easy. “That’s all?” he said. “Excuse me, Miss Geneviève. Are you sure?” “I’m certain if you let this spirit go, your life will be there waiting for you,” she said. When he took out his wallet to pay her, she shooed him out the door. “It’s getting late, and you’ve had a big day,” she said. With the windows down, Gerald drove to the square with new eyes. He was not prepared for the lush beauty of the day—the bluest sky, the deepest green of the trees, the people moving in sync. The colors made sense! He wanted to taste flavors rolling in his mouth, drink the sweet warmth of fruit, smell the air while floating in it and roll his skin in the dirt. The hunger of the living was endless. If the medicine he’d taken hadn’t purged him of this illness, if some days he saw a room in a different way, bigger and brighter, he could live with it. He could befriend it. He wasn’t crazy. He had an awareness of life and its movement with or without him. A new dimension to life opened, something that may have lived inside him forever, and he was the smallest part of it. When he reached the square, he pulled over. Helen sat with her eyes closed and face turned up to the sun. He watched her for a while until she caught sight of him. She went over and got in, and when her worried look melted into a small smile, he knew she saw it, too. He leaned in and kissed her. “Let’s go home, darling,” she said. As they drove away, Gerald took Miss Geneviève’s incantation paper from his pocket, rolled down the window, and let it fly away. Read a variety of ekphrastic poetry and prose responses to this wonderful work by our ekphrastic family member, Rose Mary Boehm. Click on image above.

The Blue Hour At dusk the air would lure us out to stroll the village beach, where sky and sea would mesh, softly stitched into a fleeting whole. The wholeness that was ours, of hearts and flesh, was temporary, too. At times my mind would send me to the hospital. Unhinged or well, I found that friends and art would bind my life to hope. My mental state infringed on my much younger, lovely wife; she traveled on her own, found another man, and asked for a divorce. My world unraveled even further when my sight began to dim. Until I could no longer see, I painted with what light was left in me. Barbara Lydecker Crane Barbara Lydecker Crane, a Rattle Poetry Prize finalist in 2017 and 2019, has received two Pushcart nominations and several awards for her sonnets. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Alabama Literary Review, Ekphrastic Review, First Things, Light, Measure, Montreal Review, Think, Writer’s Almanac, and many others. She has published three chapbooks: Zero Gravitas, Alphabetricks, and BackWords Logic. Her book of sonnets about artists and portrait paintings, entitled You Will Remember Me, will be published by Able Muse Press. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|