|

Bellini in Venice: The Miracle at the Bridge of San Lorenzo 1. I love watching my husband looking at paintings. He becomes intensely attentive, as if every nerve ending in his body is switched on. It’s not like he’s trying to figure out the nature of galaxy evolution or doing complicated math like he does when he’s working. He just stands there before the picture, fully present. Most of the time, I have a hard time understanding what he’s thinking about. I know he can build things that go into space. I know he teaches quantum mechanics at Caltech and can do multivariable calculus. He can even make a cat die and not die at the same time. Most of this is lost on me, which is why I love looking at art together. It’s something we can share, something we can dwell within. Last summer, before the world became a very different place, we were standing in one of our favourite museums in Venice, To the left was the gigantic painting, by Gentile Bellini, the Procession of the True Cross in Piazza San Marco, and to the right was the equally monumental Miracle of the True Cross by Vittore Carpaccio. It was the painting in front of us, however, that had grabbed our attention: Miracle of the Relic of the Holy Cross at the Bridge of San Lorenzo, also by Gentile Bellini. We were gobsmacked. All three pictures – the Carpaccio and the two by Bellini-- were on the same subject. The fragment of the True Cross kept at the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista in Venice remains one of the most important relics in the entire city. And that’s saying a lot in a city like Venice, which has always been famous for its relics—not least that of possessing the body of the Evangelist Saint Mark, which was smuggled out of Alexandria in 828 by Venetian merchants in a barrel of pork—how better to turn away the Muslim inspectors? In Bellini’s painting, we see the piece of the Cross –in its superb rock crystal and silver reliquary-- as it’s being paraded around the city. The painting depicts the precise moment the miracle occurred, as the relic was being carried across the Bridge at San Lorenzo and something caused it to tumble into the canal. “Such an important treasure. How could they have let it slip out of their hands?” I had crept up behind my husband, whispering in his ear. “It doesn’t matter how it fell. What is important is that it never hit the water, right?” he said, still looking intently at the picture. 2. To those who are not Catholic or Buddhist, “relics” might sound exotic. The relics of the True Cross are the fragmentary remains traditionally considered to be remnants from the cross upon which the Christ was crucified. Some have suggested that if all the tiny fragments and splinters of wood that are claimed to be relics of the True Cross were gathered together, they would fill up an entire football field. Perhaps. And yet the allure of the True Cross is hard to deny. The story began in the fourth century, when the Empress Mother of Constantine the Great, Helena, journeyed to the Holy Land intent to uncover the True Cross. Having traveled there as an old woman of eighty, Empress Helena worked tirelessly founding basilicas --pointing her imperial fingers and saying, "this is just the place for a basilica"-- and searching tirelessly for Calvary. Digging down-- in her dreams and at excavation sites-- she uncovered three crosses, and gaining divine help, she discerned which of the three was the True Cross. Case closed. But the story of the True Cross had only just begun. I had not been familiar with the Legend of the True Cross before my husband and I traveled to Italy several years ago and saw Piero della Francesco’s famous frescoes in Arezzo for the first time. We were newly married. As experts will tell you, second marriages are notoriously difficult. And this was my husband’s third try! There is something almost awkward about marrying again in middle age. How you find yourself suddenly sharing your life with someone new. Not the father of your children or your high school sweetheart—what could possibly tie two people together so late in the game? My first marriage was to a Japanese man. Having spent my adult life in Japan, where I spoke, thought, and dreamt in Japanese, I had thought marrying an American would be easier. After all, we shared a language and a culture. But it wasn’t easier. Marriage is tough no matter how you slice it. And so I have tried much harder this time to cultivate shared interests, values, and aesthetic predilections—which is challenging when you are married to an astrophysicist! In Japan, I was a student of tea ceremony. When I began my lessons, my sensei, in the hopes that the other students would take to this new and very awkward American (me!), decided we should get to know each a little. But rather than have us introduce ourselves and encourage us to share tidbits of our life history, she plopped down a massive tome on historic textiles in our laps. We were told to look at the pictures and chat about them. Tea ceremony makes use of so many historic fabrics and each has its own story—some deriving from Indian cotton chintzes calledsarasa, while other patterns originated in imperial China or traditional Japanese brocade. As we shared our preferences, we got to know each other through shared tastes. I thought it was a very Japanese thing to do, and so was surprised when my new American father-in-law, when speaking at our wedding, said that he has come to feel that liking the same things is one of the most important aspects in lasting relationships, especially between husbands and wives. That is how my husband and I started going on what we call our “art pilgrimages.” We wanted to spend time soaking up our shared appreciation of art. And the trip to Arezzo to see Piero della Francesca’s frescoes was our first such pilgrimage together. Back then, the story of the True Cross was new to us both. Having its origins in the medieval Golden Legend, it tells the tale of the Cross from its beginnings in the tree of knowledge in the garden of Eden. A shoot of the tree was planted at Adam’s grave by his son Seth. After many centuries, this shoot grew into a giant tree. The tree was later cut down to build a bridge, and it was across this bridge that the Queen of Sheba passed when she was on her way to visit King Solomon. As she made her way across the wooden bridge, she saw a terrible vision and warned Solomon that the future Savior of the world would be killed using wood from the bridge. This, foretelling the end of the Jewish kingdom, Solomon destroyed the bridge and plunged the wood into a swamp. From the Queen of Sheba to Saint Helena the fantastical tale of the True Cross was part of the Medieval imagination down into the Renaissance, when Piero della Francesca painted his frescoes of the True Cross in the Basilica of San Francesco in Arezzo between 1450-1460. It was early in the morning when we arrived at the basilica. Standing side-by-side in the apse, we had the place to ourselves. The paintings overwhelmed—almost pressing me into the ground with their power. When I turned to my new husband, I saw tears in his eyes. 3.

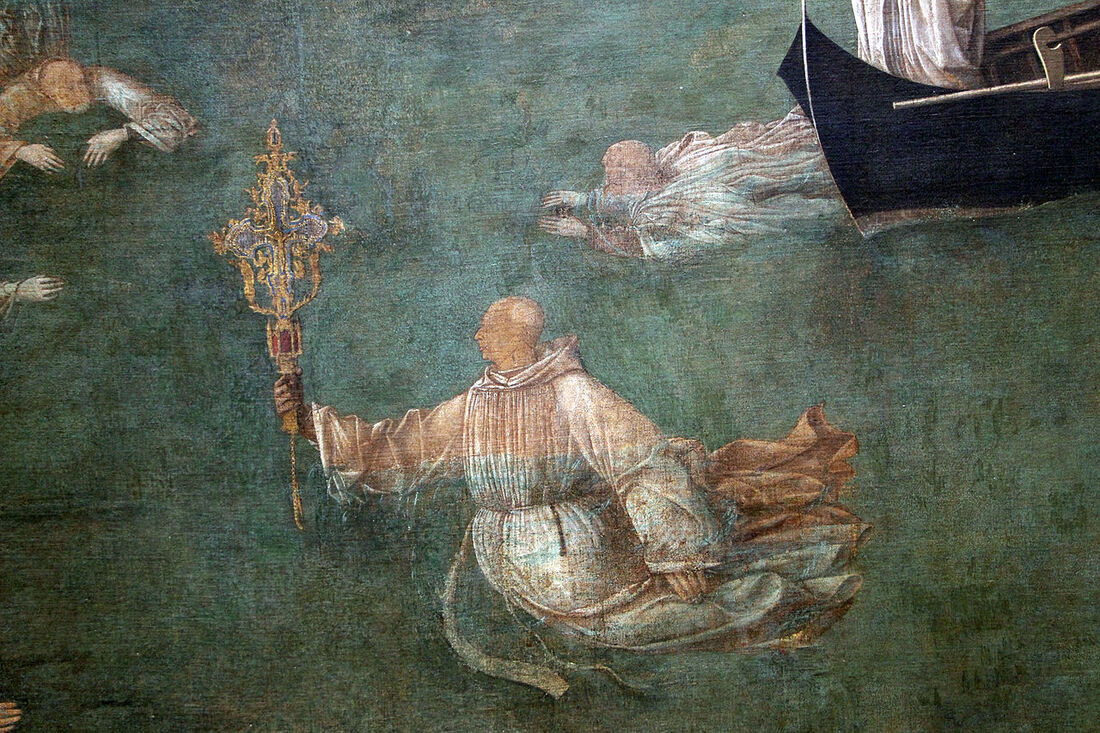

Let’s return to the Bellini painting. In the painting, the streets are jam-packed with onlookers. Un miracolo, they claimed. The miracle depicted in the picture occurred during a Lenten festival in 1370. Venice has always been known for its spectacular festivals and ceremonies-- the Sensa, the Redentore, the Salute, the Carnivale. These were times of great excitement, when the people of the city turned out to celebrate and honor their relationship with the sea, with God, and to give thanks for being delivered from plagues and floods. There was music and fireworks—the air fragrant with roasting meats and baked apples, as one record described events during the Renaissance. And Venice’s many confraternities, called scoule, played leading roles in organizing and carrying out the festivities. Today, tour guides in Venice will sometimes compare the medieval confraternities to modern-day business associations which carry out philanthropic activities, like the rotary club. That is probably not far off the mark. By the time of the painting’s completion in 1500, there were six such grand confraternities. The oldest confraternity was the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista. Founded in 1261, its claim to fame was its role as guardians of the precious Relic of the True Cross. We know the Bridge at San Lorenzo is narrow and the calle alongside the canal, even narrower. The bridge is still there. And if you have ever crossed a jammed Venetian bridge in summer, you know how precarious they can be. Plus, processions are not always orderly. The crystal reliquary containing the True Cross relic was fitted on a pole in a way that allowed putting it on and taking it off easily. And given the crowds, it makes perfect sense that if the pole-bearer gets jostled and tilts the pole too much sideways (or forward/backward) the cross might slip off. That's just the mechanics of it. Or at least that’s how my husband explained it. So the precious relic falls into the water. And who is there to save the day? We see brothers of the Scuola have dived in to try and save it. But here is where the miracle occurred. The cross did not sink into the murky depths of the canal—instead it floated above the surface, eluding the brave, would-be rescuers risking dysentery in the water! It was the pious Andrea Vendramin, head of the Scoula and guardian of the relic, who is the savior. Look at him: he floats like a beautiful swan—the reliquary held aloft in front of him, safe from the befouling waters. What a surreal and beautiful scene. Titian’s painting, Portrait of the Vendramin Family, is now in the National gallery in London. The precious relic and its crustal reliquary are still in the possession of the Scuola but the painting by Bellini, originally commissioned by the Scuola is now preserved in the museum where we saw it, along with other paintings originally commissioned to adorn the scuola oratory. 4. Today, it is hard to connect to the world depicted by Bellini. Few who view this painting believe in relics or miracles, and even fewer, I suspect, can summon the power of concentration to derive personal meaning from the work. And yet there we were, standing silently for almost an hour, overwhelmed. In front of us was a depiction of a city that we had spent the last week falling in love with, looking very much like it does today. This city that is itself a kind of miracle of beauty and survival. There also survives this painting of a chaotic near-tragedy that is transformed by artistic genius into a gorgeous light-filled tableau of serenity and redemption. And standing before it, 500 years later, two people who did not need to speak, did not want to walk away, who could not imagine being anywhere else, with anyone else, for this singular moment. Another miracle. Leanne Ogasawara This piece was first published in Ekstatis. Leanne Ogasawara has worked as a translator from the Japanese for over twenty years. Her translation work has included academic translation, poetry, philosophy, and documentary film. Her creative writing has appeared in Kyoto Journal, River Teeth/Beautiful Things, Hedgehog Review, the Dublin Review of Books, the Pasadena Star newspaper, Sky Island Journal, etc. She also has a monthly column at the science and arts blog 3 Quarks Daily. Also forthcoming in Pleiades Magazine. She lives in Pasadena with her husband, Caltech professor of astrophysics (He is a character in the essay and a character in general).

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|