|

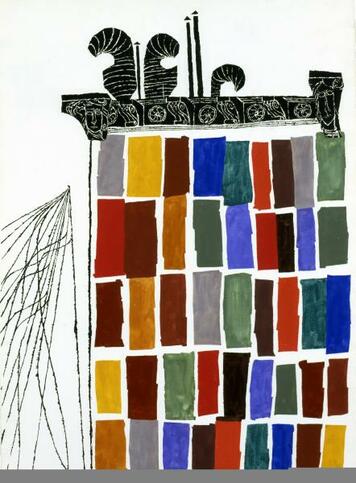

Ben Shahn’s Paterson: Behind the Factory Windows The first time I saw Paterson, one of a number of works of the same name produced by Ben Shahn in the 1940s and 50s, the print seemed almost too straightforward. The museum placard said that Paterson, New Jersey, was once known as Silk City, and the dozens of harmoniously coloured and rhythmically placed almost-rectangles, arranged within the partial outline of a building, represented silk swatches hanging in factory windows. Shahn was said to be fascinated by “dye-patterns” he saw when he visited the city, and there didn’t seem to be much else to puzzle out. But the abstraction and narrow focus of the print surprised me. I had thought of Shahn as a social realist, and his work, as I had previously encountered it, was about human activity and fighting injustice. Later I learned that Shahn, though he was dedicated to meaningful content in art, also “stood somewhere between the abstract and what is called figurative” (Ben Shahn, by Bernarda Bryson Shahn) and resisted the label of social realism. His stance proved, at least in terms of the effect this work had on me, to be surprisingly powerful. And as a result of that first encounter with Paterson, and more recently mulling over it in collections of Shahn’s graphic works, I was inspired by its subtle details to learn and remember. The outline of the factory building in Paterson affirms the ancient origins of silk. One source described the building as having “a Grecian-style façade”; and the cornice decorated with faces and medallions and the flat roof with variously shaped vents and stacks, though somewhat fancifully portrayed, call to mind older ways of making things. Of course, silk was around long before Paterson became Silk City, and Mary Schoeser calls it "one of a handful of commodities that have shaped world history.” The process of raising silkworms and turning their cocoons into raw silk began in China more than five thousand years ago. Later on, silk was traded along the mythically famous Silk Road; was used to back paper currency during the rule of Kublai Khan (1260-1294); and because it was so valuable, families and communities cooperated to raise silkworms and spin their silk. This was true over many hundreds of years in rural China, Japan, India, and elsewhere. The spindling, spidery tracks to the left of the factory in Paterson call to mind the wealth silk once brought the city. By the early 20th century, not only was the United States the world's largest producer of silk cloth, but Paterson was the epicentre of this colourful output. Tracks were needed for the silk trains loaded with raw silk shipped from China or Japan; under armed guard they rushed from the west coast to the east to places like Paterson. The silk was insured, worth as much as gold bullion, and one time the king of England was sidelined while the silk rushed by. The blocks of colour in the factory windows in Paterson make us wonder what has gone on behind them. Their appearance is somewhat mysterious, and I haven’t learned exactly what “dye-patterns” were. But I do know that Shahn’s Paterson was also inspired by an epic poem of the same name by William Carlos Williams. Celebrating invention, the poet says, “…unless there is a new mind there cannot be a new line.” Yet when Shahn gave Williams a somewhat different version of Paterson in 1957, Williams is said to have found the work too abstract. “I'd like to have seen a big figure of a mill-worker applied all over the surface of it with the windows showing through,” he said. Williams himself only mentions silk and strikes and labour disputes a handful of times in his poem, but both men surely knew that in the days when silk was king the workers were worked hard by the factory owners. How would new minds respond to enterprises that ruthlessly exploited immigrants and children? I.W.W. organizers, at least, responded by helping workers oppose long days and low pay. But though a 1913 strike went on for over six months, the mill owners broke it and things went back to the way they were. Well, not entirely. Because between 1881 and 1900 there had already been over 130 strikes in Paterson. And even before 1913, companies had begun to move their operations over to the next state – Pennsylvania – which wasn't so well unionized or so stringent about child labor laws. That was where my grandmother became a silk mill worker in 1910. I remember her voice, sounding plaintive and aggrieved, as she told me her family made her quit school to go work in the mill. She was twelve years old. She said it was hard work and she didn’t get enough to eat. She said the silk dust hurt her eyes. She said she wanted to be in school. Sometimes, sitting in my own classroom, I would think about what it might be like, standing in the service of a machine, watching the slick silk thread, expected to mend it pronto if it snapped. But though Mother Jones, the famous organizer, had led a march of child workers in Pennsylvania in 1903, grade-school-age children continued to work in the mills for decades, my grandmother among them, until child labour was finally outlawed. Paterson is a serigraph, printed using the silk-screen method, which reminds us that silk still has its uses. There is no figure of a mill worker as Williams might have wanted, no woman tending caterpillars, no young girl keeping melancholy watch over the machine she serves. Yet I find in Paterson a dignified commemoration of the process of making and dyeing fabric, whether a century ago in Paterson and Pennsylvania, or longer ago in China or India or Japan. Calling to new minds with its new lines as its abstraction universalizes its content, Paterson makes us wonder what’s gone on behind those windows, reminding us how hard human beings (even children) sometimes work and how important it is to know how things are really made. Alice Whittenburg Alice Whittenburg's short fiction can be found online at Atlas & Alice, The Big Jewel, Eclectica Magazine, outwardlink, Pif Magazine, riverbabble, and elsewhere. She is coeditor of The Cafe Irreal, an online magazine of irreal fiction, and of The Irreal Reader, Fiction & Essays from The Cafe Irreal. Her website is at www.alicewhittenburg.com.

2 Comments

12/19/2019 02:23:21 pm

It's fascinating to know that the early 20th century was the time where Paterson was known for being one of the major silk producers in the world. Since I'm eager to know more about the facts that surround the history of this city, there might be some things that I'll find more interesting if they're woven in a different way than the ones that I know from the museums. I think I'll try to buy some fictional books regarding Paterson so I'll get to enjoy these facts in a different light.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|