|

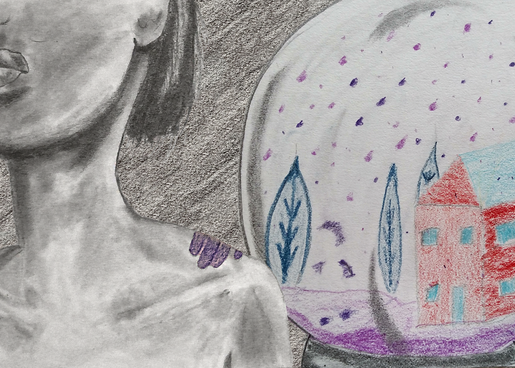

Bird's Eye “Everyday, something else about you goes,” she would laugh, picking a stray hair from his shoulder or an eyelash from the side of his nose. She liked something about how lax his body was with its property. It meant he was not distracted by the question of where to be, not like the others who insisted one way then went another. Only one man had actually left her like that, left quite so suddenly. Maybe two. “But one or two is all it takes,” she would tell you if you called her on it, “for a boring woman like me.” And she might laugh then too, though afterwards she would not be sure that boring was what she meant and she would feel the shadows across her cheek and neck and her mouth would be dry waiting for him to reassure her he still understood. When such reassurance would come, and it would come, she would of course not believe him, but his words, students of his drifting eyelashes, had a way of drifting just short of her ear to catch on a shoulder blade. They let her know he wasn’t offering false promises. It seemed clear to her nothing as worth listening to as a lie would be so casual. What she would have actually meant was that she was a woman who stayed put, holding again and again to what was last given her, so she never knew how well the held held back. Her imagination was skilled in filling in the blanks, laying out just how any man or woman—yes even him, no not her—could leave with no because. This was how her imagination created the shadows and how the shadows warned her to stay in one place since she was not wanted in others. But he, at least his body, didn’t seem to understand the difference between one place or the next. And though she maybe somewhere knew if his disintegration kept up she would eventually be alone, she knew this only as well as she knew he wasn’t quite gone as long as he was going. He, on the other hand, had reservations about his condition. He didn’t share them liberally, considering it silly to complain over what was obvious and seemingly beyond one’s control. And he didn’t want anyone to think it was vanity. Quite the opposite, he especially liked the receding hairline. As a teenager, thick auburn waves encouraged in him the occasional fantasy that he was special. But he had learned in good time, as most men must he supposed—taking only a generic sort of pride in his ability to relate well with reality—that he was in all significant ways just as most men are. What he wanted now was only to be decent at being this, being a man just for one woman, just lucky enough there was one woman foolish enough to want him. Nothing special. Unfortunately, as long as his good features persisted, the repeated interest of repeated women repeatedly called his bluff, leaving him disheveled and ashamed. He was, above all, embarrassed by the youthful fantasies prodded awake by these women, insignificant women in all other ways and not themselves the characters of the fantasies they inspired. And even on top of this, he was embarrassed that any part of him found these fantasies persuasive still and all of him might have even found them so if he allowed it. But a receding hairline, though she called it sophisticated, was a highly efficient anchor to tether an evasive insecurity. It let him walk from other women with a simple sense of defeat, the way most men are defeated every once in a while without ever having tried. It meant when he said all he had was all he needed—just her, a good woman used to her flawed man, victims of time as are we all, and he was used to her—his consolation had authenticity to it. It left them free to find no better explanation for their love than that it was what they had agreed to without concern for any externals. He did not mean to complain about that. He did not mean to complain at all. Still, it seemed strange. The hair, soon joined by peeling skin, tarried on his belongings, his desk, his car, his tennis rackets. This debris made a trail for anyone with an interest to follow his activities, as though where he was and what he did deserved a permanence other people’s actions did not. It was as bad as a woman’s gaze. He did not like thinking he, meaning the parts of himself he did not share with humanity as a whole, was all that deserving. “The formality of the human condition,” he would say, referring to ideas he garnered from the right crowd of contemporary thinkers, “is beautiful, each of us filled in by circumstance and scratches history leaves behind, but nonetheless, all at base a similar form.” “And that is all that is necessary,” he might add internally, reassuring himself that love and happiness were themselves a sort of human formality, their being-had or not-being-had leading to the same conclusion. “Since we’re all the same when it comes to capacity,” he might then wrap-up, meaning the capacity to grab for something, fail or be satisfied. This was of course the sentiment she saw in his casual body. Lives, she knew he believed, were all variations of the same, so he might as well continue with the one he had started. And he would have, shedding and peeling be damned, if only he had not begun to disappear altogether. Generally adept on his feet and not particularly clumsy, not more so than most, he began to find himself scraping his elbows or banging his toes while passing almost any corner, stair or doorpost. His fingers too became accident prone, daily being discovered too close to the edge of a knife or just inside a heavy door after the damage was done. The thought crossed his mind first metaphorically during an inner admonishment and defense: “It is as though the ends of my limbs wander off!” At one time he might have been amused with such a creative phrase, sharing it with her because she liked words and he liked how she laughed at the things she liked. But this thought gave him an eery sensation of knowing too much and too little all at once, and he didn’t think he would like her laughing at it. Of course, after some time—as it so often goes, he vaguely acknowledged—he grew accustomed to the fading in and out of the thinnest edges of his skin, the ones most apt at getting caught in life’s crossfire if left unattended, and when he finally mentioned to her what he suspected was the problem, he could say it with a grave mundanity. “Sometimes,” he simply said, “my fingers disappear.” It made him think, he didn’t know why, of how he liked to watch the delivery men outside the grocery move boxes of apples onto a conveyer belt that brought them from the truck into the store to be placed in bins, knowing eventually a few of them would go from the bins to his bag. His body was disappearing he told her, but it was just a body doing something slightly unusual, and in each delivery there were among those many apples ones that fell to the floor. She did not believe him easily. It was not that disappearing was so different in her mind from disintegrating, not in what it could tell her of his character, but, for the most part, the men she knew who had left always took their bodies with them. The bodies did not go first. No, she was quite certain, men did not really disappear. Sure sometimes, well, sometimes he looked strangely gaunt, and—but this must have been in bad light—his nose or ear or pinky finger would sometimes look, look, as though it weren’t there at all. But men, in a bodily sense, speaking strictly of the facts, did not disappear. So she did laugh, and teased, calling him the disappearing man, meaning mostly something that had nothing to do with what was happening. Or was its opposite. She meant, as she had always suspected, that slowly, slowly his body would be all she’d have left. She had watched him over the years, watched him work diligently to secure a very specific amount of contentment, the amount recognized for being good at keeping men away from mourning lost expectations, expectations such as the ones he assumed most men, now and again, do fall lazily and soberly into desiring, as even he, less so now that he was older, did occasionally desire and mourn. She liked watching him grow used to himself and used to her, liked knowing her body, also not going anywhere, if anything, just making more claims to the space allotted it, excited him only so much, feeling him touch it only so firmly. And if at times he asked for something out of the routine, getting creative as men do during play, what he came up with was never very taxing, never more than any woman could give. Desire is what separates us, she knew, because a man had left her once when he desired something different. “Desire casts a big shadow,” she thought she might say if she spoke more like him. But the disappearing man let his desire disappear and so she knew his body would stay exposed and with her. There was something she liked about this. It felt nice to think maybe then she could disappear too—“slip into the shadows,” she might have said if she were still thinking to talk like him—and still not have to be alone. She did not say it like that though, only laughed again, liking laughter because it made her feel she could be distant from her self and nothing bad would come of it. It made her feel that maybe there was nothing to all this pleasure and pain she ran after or away from, nothing much to expect and nothing much to regret. It made her feel close to him. He liked how she laughed too because he did not see the shadows himself and only her laughter echoed out where they might be and that something bothered her but she kept it from him, which he appreciated. This was not how he explained it to himself. To himself, he thought she laughed enough for the both of them, thinking time and again it was good she laughed for him, at him, or he would be concerned and think something was terribly wrong, and he would desire to be ordinary and his desire would separate them. He felt close to her when she laughed and thought maybe he was silly for taking such notice of himself. Maybe disappearing is just what happens to some men. “Probably men disappear all the time,” he thought, “so often we just don’t talk about it.” Near the end of March, his torso would not materialize for a week. This was when her laughter stopped and they decided it was time to seek medical assistance. It was nearly summer after all and they enjoyed days at the beach as much as anyone. A man without a middle would get them talked about, as would false modesty, so there was no way around it. The doctors did not know what to do. One said he did not see the problem, equally not noticing that his patients did not enjoy the pun. They laughed afterwards though at the doctor’s coffee stained bark of a laugh. It was good for her to laugh again and for him to laugh at all and for them to laugh together. Doctors do not know everything they agreed, continuing to go to one after another since they were not going to the beach anyway. “Maybe some men just disappear,” he said. She told him she didn’t know that that wasn’t the case, but that she did miss putting her arms around his waist. “Well,” he said, “just sling them around my neck for now.” Which worked until that disappeared too. The neck, the elbows, one thigh, all the toes, both earlobes and the lips all invisible one breezy summer day. After that, they touched much less often. He wondered if things would be different if he at least still had his wavy hair. She assured him that had nothing to do with it. It’s just difficult, they both had to admit, keeping up commitment to an inside that has so little outside to overlook. One day he came back from the office and all there was to him was his suit. “If you take off that suit,” she told him, “I might as well start looking elsewhere.” He left it on. Not only for her, but because he did not know where enough of his body was to undress it and worried even if he managed that, he would not be able to find himself again to put the suit back on. He imagined how the suit would lie then inanimate on the floor, watched over by an emptiness, and he wondered if he would still cast a shadow. “It is maybe something of an accomplishment,” he thought, “to be so indiscreet, so universal.” But no one else was quite as common and it left him, even with the suit, more than a little self-conscious. He fantasized—as he still had his fantasies, as he had had all his life, blushing only over that young one in which he imagined the others coming true—if only his skin would come back, they could be ordinary in their own private way, like everyone else again. Over the summer and through the winter the suit became worn and she grew afraid if he moved too much it would tear. She asked him to stand still and suggested the backyard, explaining that this way he could watch the birds. He had liked, she remembered him mentioning, watching birds when he was young. Compared to other men’s desires, it was the sort she would not remember ordinarily, but she didn’t think to compare him anymore. So he watched the birds. He watched the birds and thought about flying, feeling sometimes as though he were flying himself. Or floating perhaps was the better word. The truth was, his thoughts relied less and less on words as words became more and more unable to find his mouth. Sensations instead waved through him, or what he took for himself, which was the space around the suit, a space spreading daily so that soon it reached the top of the trees and deep into where the earth breathed heavy, moist and dark. “If I could just expand less symmetrically, I might fly,” he thought a day or two before words made no more sense to him at all. She might have laughed at that, but he wasn’t sure anymore. The doubt reassured him that he missed her laughter. She still laughed he had reason to suppose, as he supposed she was still in every way as he had left her, not supposing that his leaving made that impossible, not seeing himself as having left. But the sound of her laughter when it did wade through the air now and again was not now one he could distinguish from all other noises, as noises, like colors, tastes and touches, did not know anymore where to enter him or how to pass him by. One or two snagged on the suit, but so many more got through the cloth they soon covered him and then slipped into him and out of him so he was not covered by anything and could not sense his own beginning. It was not long until only this single strong sensation of being nothing and nowhere told him he was still something, still somewhere. He was in the suit, wasn’t he? Yes, of course. He was watching the birds. Watch, they fly very close, gathering his expression in their wings. Tikva Hecht Editor's note: This story was inspired by the painting, Uncle, by Whitfield Lovell, which you can see here. Unfortunately, we were unable to contact the artist for permission to show the painting. The image above was not the original inspiration for this story, but it was created especially for it by Dov Alpert, a colleague of the writer. Tikva Hecht is a writer and content producer based in Toronto. She holds an MFA in creative writing from UC, Riverside, and an MA in philosophy from the New School for Social Research. Her poems have appeared in several print and online publications, including CV2, Canadian Literature, Ghost Town Literary Magazine, The Broken Plate, Jones Av. and the Mima'amakim Journal.

1 Comment

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|