|

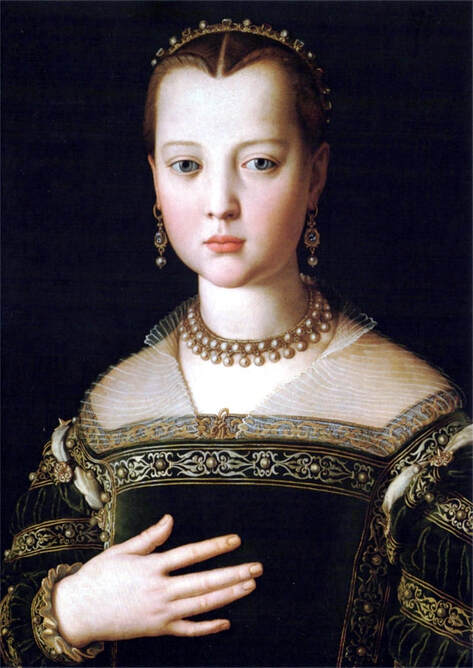

Blend Mother of pearl. It’s always sounded like some sort of expletive. You spill your wine in your lap: Mother of pearl! You miss the green light: Mother of pearl! Ever the intellectual sophisticate, this was what went through my mind upon entering the round room in the Uffizi back in 2001. The room was dim and dark red. The dome was delicate china blue and covered with beautiful luminous expletives —that is, mother of pearl. Light came through the square windows at the top and from somewhere above them, and reflected off glass cases and still-glossy paint. My stomach rumbled. Looking around at the people in frames, I could distinguish only that they were faces and wearing heavy looking clothes. The face of a large woman reminded me of someone. They all resembled each other, a family reunion through the space time continuum and put on display for tourists, the elderly, the has-beens, the searching, the pretentious, the hungry, and the jet-lagged awkward self-conscious college kids like me. But something else was going on in time and space. I was flashing back to my seventh grade self, leaning over my large paper, fingertips sticky with many colours, the smell of oil pastels, and cursing my own ambition: There’s no way she’ll ever look like the real girl, meaning, the real painting. I’m not sure I ever thought about the girl being painted. Her name was Medici, wasn’t it? I tried to suck in my stomach more. Italians are so freakishly beautiful. Almost four weeks later, I bent over that paper and gave myself headaches from looking back and forth from the magazine picture to my sketch. I redrew her eyes for an entire class period before I got them right. Pastel was terrifying. A mistake had to be worked with or transformed completely. There are no do-overs in oil pastel when you are 13. My greatest torment was that I never could blend her cheeks well enough. And to make matters worse, I had discovered that my friend was doing the same girl in another class—and my friend’s girl had been chosen to hang in the hallway between the lunchroom and the office. I would never have such fame. There would be no glory. My hands were smaller when I was thirteen. I was meticulous. I wanted to be like my teacher, Ms. Dempsy, so I smeared the colours with my fingers, not the tissue like the other peasants. “Don’t use black. Anywhere. It’s too harsh.” I concentrated most on my girl’s eyes. I made her pupils dark blue. I frowned over my page, penitent. She must hate the way she looks! I was letting her down. In my head, I’d talk to the face as it materialized on my paper. I know. I’m trying, but I usually don’t draw both eyes. I’m sorry. Standing in the red room, I thought the large portrait of a woman looked like my girl. Perhaps her mother. Perhaps her as an adult. A ridiculous revelation came to me: perhaps she’s here! In this place somewhere! The faces came into focus. Some were older, some had brown eyes, one was smirking. A man looked uncomfortable in such a stiff chair. I turned to the left. I was excited. I forgot to suck in my stomach and stopped trying to look contemplative and smart even though I had three fresh zits and my hair was not coloured. Each face knew something I didn’t yet. They kept it close. Their focused eyes saw beyond me. I looked up. She was there. High on the wall. She was taller than me, even though I was the older one now. I was surprised to see her though I’d been searching for her. Yet there she was. Big as life and just as I remembered her from my torn out magazine page. Small plump coral lips, content but not smiling. Smooth round coral cheeks. Those deep, lashless eyes—I knew they were green, but I couldn’t tell from where I stood because of the glare. Her brown hair was severe and parted so that her face was a heart. On the top of her head was that small thin crown or hairpiece evenly spaced with pearls. My fingers remembered the pearls. Her necklace was gold and dropped pearls as well—which I had tried to copy using very artist-like swirls of white. Her dress was deep, deep green. Velvet. Juliet sleeves—white poofing out from below her shoulder where her arm began. Long elegant gold pearl drop earrings—a child dripping with precious things. One pale hand, girlish fingers, spread deliberately against her flat chest. Her skin was so creamy. Coral and cream. “To make her lips look shiny, put a streak of white here.” I looked to the side and read the brass plate: Bronzino. Maria dei Medici. My eyes moved back to her face. I wondered what her teeth looked like. I looked at her eyes. I backed up to the crimson rope holding the visitors in and stood on my toes to beat the glare. I wondered who her friends had been and if she had seen her portrait and liked it or if she had wished she looked better. I wanted her to see me. I wanted to be remembered. Christina Rauh Fishburne Christina Rauh Fishburne is a writer, mother of three, and army wife currently living in England. She has an MFA from University of Alabama and blogs at smilewhenyousaythat.wordpress.com. She will cheerfully finish your cake for you.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|