|

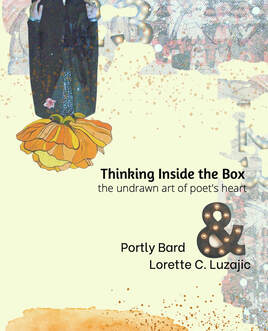

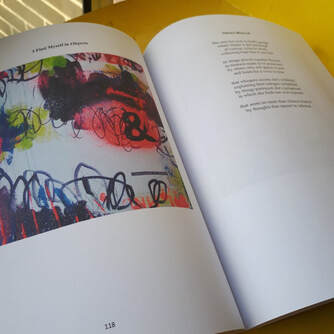

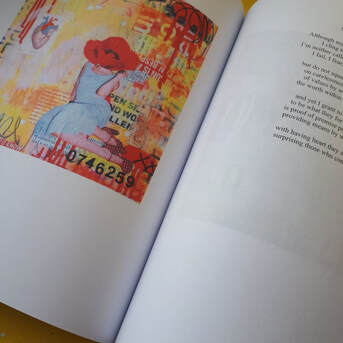

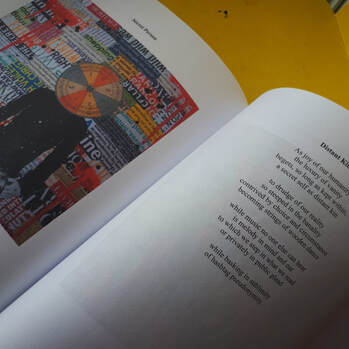

This past summer, an ekphrastic collaboration between Portly Bard and Lorette C. Luzajic came together as a full colour collection of visual artwork and poetry. The project contains a creative dialogue between them about ekphrasis, art history, and writing; an essay responding to Lorette's body of mixed media works, and over 100 sonnets, responding to Lorette's collage paintings. Below are two interviews between the artists. Lorette C. Luzajic Interviews Portly Bard Lorette C. Luzajic: You have a very broad appreciation for art styles. Even so, since you are a writer who is unusually faithful to traditional forms, your attraction to my raw, urban, surreal, pop and abstract art is a surprise. What happened here? Portly Bard: Truly novel creativity fascinates me, especially when it clearly springs from intensive interest in the tradition it expands. Beneath your aggressive post-modern cultural immediacy, I found ingenious exploration of the human condition and an appealing legacy of influence. And your haunting poet's heart always seemed present. Even where abstraction was dominant, I always sensed intent and meaning lurking -- with assembly required. It was that thoughtfulness, I think, that made me connect so readily with what you do. I actually bumped into your amazing art as I was trying to research your writing to see if my work had any hope of catching your editorial eye at The Ekphrastic Review. As a traditional, mostly short form poet, I was also immediately taken with the very challenging small size of your signature square canvas and what it was forcing my eyes and mind to do while echoes of rumbling meaning got clearer and clearer as I got nearer and nearer. The fact that what seemed like contemporary looking decor from a distance could dissolve, as one approached, into curiously eclectic, cleverly titled contemplative juxtaposition was mind bending. I was hooked. Lorette C. Luzajic: How did it come about that you wrote an entire book’s worth of sonnets about my work? Did this evolve spontaneously? Did you write one and then another, and find yourself at a few dozen? What drove you to keep going and why? Portly Bard: The effort sprang from the success and failure of my early submissions to The Exphrastic Review. For all the selfless effort you were putting in there, I thought more of your work should appear on those pages. I first submitted your stunning, elegantly simple Chrysanthemum Queen. I have long had a passion for the equally simple elegance of the diminished iambic tetrameter couplet sonnet, and it seemed to be perfect for my notion that you had inadvertently done self portraiture. When you agreed to publish the resulting "Self Portrait Seen in Floral Queen," and when it drew surprisingly positive reaction, I thought I might be on to something. I responded by trying to push my luck with your One Apple on Top, another very simple but very powerful image. When you also agreed to publish "You're the Apple of My Eyes," I began thinking your art could perhaps become a very regular feature on your site or perhaps have its own permanent place there. But when that image and verse got almost no reaction from readers and fellow poets, I realized that my first effort was a rare exception. Continuing to submit such work for publication was clearly not going to help your cause appreciably. Fascination with your small works still constantly nagged me, but by that time, I had also become intrigued with the TER biweekly challenges and I was trying to tackle regular submissions based on other artists. I kept wondering, though, whether I could handle your more complex works in the same diminished sonnet form. And since you personally seemed to enjoy both of the first two efforts, I began to think a publish-me-not bouquet, maybe a dozen or so of such verses, would be the perfect way to thank you for all you were doing with The Ekphrastic Review, which I thought was remarkably adventurous and advantageous to so many. The challenge of reducing your work to my beloved single thought form was daunting, and that kept me chipping away at it. I soon had about a dozen and a half drafts, and I began to believe the gift idea was actually going to be worthy. Yet it seemed like even a dozen finished works would no longer be nearly enough. I thought if I just kept going, the muse would let me know when the collection was big enough -- and good enough -- to send it to you. When it began to look like I was going to get to at least fifty, though, I started thinking that binding them into a book might be a way my gift could actually serve a useful purpose in your journey. My objective then became something akin to portraiture -- a representative, revealing sample of your signature works, a "gallery" big enough for people to lose themselves -- and find themselves -- in. And that also meant trying to keep it as current as I could with your ongoing production until it became actionable. It just felt to me as time went on that a useful book was going to need at least a hundred images if the muse could sustain my momentum. When I simply could not fit some of the verses into my form of choice, I realized that more like a hundred and twenty drafts would have to be the goal. And when we finally went to a layout that could also accept the non-conforming verses, that's about how many I had done. Even so, though, I never did get to the truly representative sample I had envisioned. And that troubled me, but I was satisfied that we had enough to make going to press viable. The similarity I saw in the constraints we each took on and the sheer joy of our very rare ekphrastic juxtaposition kept me at the grindstone. It was certainly not effortless, but each of the images led io a verse that was rewarding in its own way. The richness of your work took me as far as I got for the book, and I'm still going. Most of my more revent effort, however, has been more focused on your equally intriguing larger works. Lorette C. Luzajic: What attracts you to traditional poetry? Do you ever experiment with other traditional forms or modern forms? How did you choose the sonnet, and why did you stay with it? Portly Bard: I was raised on traditional poetry and its song lyric equivalent. I was schooled in it by amazing teachers and professors. I came to understand that poetry was poetry because it made the meaningful memorable or the memorable meaningful. I was taught to respect form, metre, and rhyme as poetry's oral tradition roots and as the strengths of its performance potential. I knew the meaningful and memorable criteria could cerainly be met without form, metre, and rhyme elements, but I also knew the task became extremely difficult. Yet I knew as well that those three requirements would tend to compel my creativity, not constrain it, very much like the four small equal sides of your signature art canvas. And they would naturally move me toward meaningfulness and memorableness. They wouldn't necessarily guarantee getting there, but the better they were used, the closer a clever idea would get. My allegiance to form, metre, and rhyme therefore became unwaivering. I have, though, also dabbled in traditional Haiku, which involves form but requires neither metre nor rhyme. Flash fiction in its briefest forms also tempts me, but time is difficult to find for strengthening the mindset and the tools it requires. All that said, well done ekphrastic writing of all sorts appeals to me as a reader, whether I consider it poetry or not. I have always loved the iambic tetrameter couplet sonnet because it seems to be the upper limit of deliberately small form and length in which a single, truly memorable and meaningful point can be made and supported. When you write them you can recite them That's poetry's acid test. And it's what your signature works seem to demand. I in fact use that form for nearly all of my ekphrasis. I try to make a single, powerful point that is dependent on seeing the art first. And one that sends the reader back to the art immediately for a closer look. Expression limited to 112 syllables was simply as close as I could reasonably come to matching the visual challenge of your often complexly executed twelve inch square canvas. But occasionally, it just didn't work well enough, and I opted for a slightly different form or a somewhat longer one. My first allegiance is to the art, not the poetic form. And that's been the case with all my ekphrasis. If the small sonnet just doesn't work, I opt for rhyme and metre form that is appropriately longer or shorter. And far more rarely, Haiku seems ideal, but I have yet to use it for your works. I enjoy the lower limits of small, single thought expression too. Though extremely challenging, ekphrasis in couplet, quattrain, and particularly limerick forms can also be very powerful. Though I have not used it much for ekphrasis yet, the limerick form (with all its metrical variations) is also one of my passions. It can become the perfect miniature factoid, story, humorous bit, truism, or classic ode. And it can be seamlessly linked in an expository or narrative chain. But your work, far more often than not, is simply ideally suited to the compact sonnet. Lorette C. Luzajic: Tell us about your interests in art history and your literary tastes. When and how did you discover joy in reading or writing ekphrastic works? Portly Bard: As a very long ago liberal arts student, I was compelled to appreciate art history and the philosophy of art -- but neither required coercion. So I was forcibly but blissfully blessed with a "big picture" understanding of visual art's cultural and philosophical evolution. And I have since developed a reasonable grasp of its global market and vertical national industry traditions. I am not, however, an avid student of any particular place, period, or school of thought. I enjoy researching individual works and artists that evoke my muse, so the last four years of investigating your bi-weekly ekphrastic challenges have been an enormous joy to me. And so has reading The Ekphrastic Review every day and following major art news stories on the Internet. When it comes to visual art, I am most intrigued by unique craftsmanship, preservation of history, and poetically evoked thought. As for writing, I appreciate good work of all sorts but I was never much of a novel reader once I put the obligatory classics behind me. Classic short stories, however, still fascinate me, and I like to read the sort of poetry I write, both returning to the masters and exploring the work of fellow pupils. Unfortunately, writing and keeping up with the world leave little time and inclination to savor modern literature. But I do enjoy reading ekphrastic work of all sorts, especially your challenges where the observation, thought, and technique of multiple writers take on the same storied object. I was first exposed to ekpkrastic writing in that now very distant seeming pursuit of my liberal arts education, and I actually dabbled in it on rare occasions thereafter, but I owe the passion I have developed for it to your journal, The Ekphrastic Review. Four years ago, your flagship instantly made ekphrasis an enduring fascination. Lorette C. Luzajic: What are your hopes for this particular project? How have your intentions, hopes, and expectations for this project evolved? What do you want people to take away from your poetry in response to my visual artwork? Portly Bard: I hope we have created something that will serve your journey well. I want people to appreciate all you do, and I want that to make good things happen for you. I want our readers to look at your work again as soon as the last line of my verse rolls past them. I want them seeing far more clearly the thought, the ingenuity, the human sensitivity, the cultural urgency, and the respected influence of your craft's history that you so carefully layer. I want them to keep looking until their own thoughts strike them. I want those thoughts to make them realize they ought to know more about you. And that they ought to come back to your work again and again. That's what truly appreciating it requires. I originally imagined the book would be a simple, speaks-for-itself ekphrastic gallery of your signature square works. Then, for a fleeting moment, I envisioned it morphing into an ekphrastic textbook of sorts by incorporating an essay I have long pondered publishing. Ultimately, though, I dismissed that idea, realizing the book needed instead to incorporate your voice and emulate your art, to engage our curious juxtaposition in a layered set of conversations ending in the art-to-art gallery. The insights into you, under the banner of our title, would be many, varied, and spread throughout those conversations, requiring precisely the same sort of attention to detail your art requires. I like to think of the book now as an assembly-required portrait. In addition to incorpoating your voice, you wound up doing two things that made our emulation very special. First, you found time to reverse the ekphrasis process by visually interpreting two of my works, including the title (and final) verse in the gallery. Then -- at the eleventh hour -- you added the ingenious front and back covers that literally turned the book into art on the shelf. That was a remarkable touch. As the book evolved, I kept wanting it to be a way I could say thank you for all the ways you have found to touch people's lives -- as an artist, a writer, an editor, an educator, a colleague, a mentor, and a sweat equity philanthropist. In my wildest dreams, I wanted it to generate money to support The Ephrastic Review and to heighten awareness of visual art as a global cultural legacy precariously supported by very hard working talented people, often at great personal sacrifice. More realistically, though, I simply hoped the original intent would be served, that it would indeed become a useful resource for you. I hope it helps convince people to comission your work, to acquire your art, to license the use of your art, to invite you to teach, to invite you to be a symposium voice, to participate in your workshops, to buy the ekphrastic resources you have curated, and to submit work and comments to the daily page, the challenges, and the contests of The Ekphrastic Review. Your journal has become a remarkable gallery of global art history and contemporary artistic aspiration. It is a particularly stunning tribute to the long but little known history of female visual artists. And it is a creative writing resource like no other. Portly Bard interviews Lorette C. Luzajic Portly Bard: For the front cover of the book, we originally planned to use our last image, your visual interpretation of my final (and title) poem. As we were finalizing the manuscript for publication, however, you decided instead to borrow a bit from that image digitally and essentially go about proving that someone could indeed very well tell our book by its cover. The ingenious result speaks magically to my experience with your art and to the very thoughtful character of your creativity that can often seem deceptively spontaneous. What was the thought process that got you to the idea for the front-to-back cover at the eleventh hour and then through the iterations required to be satisfied with your work? Lorette C. Luzajic: My work is often as spontaneous and impulsive as it seems, Portly. I appreciate that you enjoy the cover so much, but the transformation is simply a result of a problem- the square shape of the image did not work to my aesthetic satisfaction in the profile rectangle of a book cover. Perhaps what they say about necessity being the mother of invention is often behind improvisation that leads someplace interesting. In working on the cover design, I simply felt at the final hour that I didn’t care for the design using the artwork as a square. But changing the imagery to something else was not suitable- the image was important to the cover because it was symbolic of the project as a whole. So I just started playing around with the elements inside the artwork, freeing them from the constraint of the square. I moved them around until I felt that it worked. Portly Bard: Coming from someone who describes her philosophical inclination as "post, post, post modern," your tolerance of my brief, traditional poetry teeters on the brink of unbelievable. Your willingness to do reverse ekphrasis on my verses is even more stunning. You did two for the book. The one that appears in our "primer" seemed to come very easily, but our title (and final) image required a number of iterations. How did "imagizing" my work, particularly the title verse, affect your creative approach to the task? Lorette C. Luzajic: My weakness and my strength has always been that I am interested in everything. My tastes are exponential. Some may be surprised to learn that I love 17th century Netherlandish still life as much as I love neoexpressionist art like Jean Michel Basquiat, but it becomes very apparent quickly that my work, whether written or visual, is a result of consuming voraciously from many tables. If once upon a time, I was hoping for a place to land, now I embrace my disparate passions and try to infect everyone else through my art, editorial persuasion, and teaching. It has always been this way inside my psyche. My palate longs for the whole world as much as does my palette! I adore Korean and Ethiopian cuisine as much as Italian or Greek. In music, I find transcendence in electronic trance music, in delta blues, in classical, in pop music, and in old time rock n roll. Collage is a place where I can gleefully display the deliciousness I find in contrasts, in juxtaposing parts that supposedly don’t go together. I take absolute delight in unexpected contrasts and juxtapositions. Your work is astonishing to a person who is all over the map. The focus and constraint that a sonnet practice demands is something I envy. Approaching your poetry with my art was a very similar process for me to the way I approach art with my poetry. I spend some time with it, procrastinate a lot and do other tasks or projects instead, all the while consciously and unconsciously incubating impressions, gathering elements, then something comes together in a burst of sorts. If it works, I leave some space and revisit it for balance and breadth. If it doesn’t work, I pull it out time to time, then put it away, then do it again until I give up, or find the spark that pulls it into place. I work very much at impulse and intuition and follow any idea or image where it leads me. Sometimes the finished result has very little to do with the original inspiration, and sometimes it is profoundly intertwined. Portly Bard: If we had bound our handsome hardcover version with a bookmark ribbon, where would it be placed in your personal copy and why? Lorette C. Luzajic: As much as I admire this impressive body of poetry, each one a window into my own imagination, through my artwork, as well as a window into your own heart and mind, the opening essay is my treasure from you. It blows me away that someone could see through the wild barrage of imagery I produce, and find the words I don’t have myself to explain what it’s all about. If I had to pick a favourite poem, perhaps it would be “Keep Going,” inspired by the piece When You’re Going Through Hell, Keep Going. In this work, my borrowed muse was Sir Winston Churchill. This complex, larger than life character who was so pivotal in the freedom we enjoy also blundered terribly and was privately plagued by every error. He didn’t let his anxieties and missteps imprison him. Instead, he studied voraciously, wrote ten million words of history (give or take), and took up painting to manage his mercurial moods. And a little bit of whiskey. I love how your poetry boils this all down into a few words, to the essence of what it means to keep going. Portly Bard: You have recently launched a Tarot ekphrastic prompt booklet and contest, and you have often shared the tale of cementing your self-confident artistic ambition by successfully piecing together Tarot card archetypes as a college student. I allude to that pivotal event at your work in "Fortune Teller." How would you react to a biographer suggesting your "signature squares" are the iconic remnants of that seminal moment? Lorette C. Luzajic: As my Dad taught me, God has many ways of showing up. School was all about getting organized and getting my life together, but I was floundering badly. In those years, I was in the deep end, running from trauma and dealing with profound mental illness without any understanding of it yet. The gravity of graduating, which for me at the time was incredibly difficult and exhausting, and knowing I could not do the work I had taken out a lifetime of loans to learn to do, was monumental. Although things didn’t get better anytime soon, my path changed direction and that would ultimately be important. I took a rest in hopes of getting a grip, and during that time decided to learn about Tarot art and symbolism. The best way to do that was to make my own cards, I thought, and immersed myself in a stack of magazines with scissors. I became intimate with the archetypes, symbolism, psychology, and imagery of Tarot, but I also created a cohesive body of collage works, all 78 cards. I discovered there was enormous release as well as learning involved in creating artwork, and I also found a language of symbols that would prove helpful in my journey. Although I was dazzled at the time by hope of magic, it was the psychological tool of symbolism and the chance at organizing and expressing my ideas that later proved most valuable. It was also about my own lifelong passion for art history finding a way that would come together- the Tarot collages were a portal to how collage would eventually bring everything disparate into my hands. I never stopped creating art from that moment. I let the momentum build. It took me through some wild rides, through life and death and unimaginable chaos. I kept writing, I kept making art, and slowly but surely, everything else fell away. Portly Bard: I have hoped from the beginning of our effort that the book would become a useful resource for your creative journey. You invested a great deal of time and energy in our effort knowing that such books tend to generate very little revenue. How will you put what we have done to use and what do you expect the dividends to be? Lorette C. Luzajic: I learned a long time ago that the things that bring me the most profound pleasure and meaning will bring the same to a few others, and that is the end of it. If I required a massive audience or millions, playing the lottery would be a better game plan, among others. I had to come to terms with that once upon a time, but because my love of art and literature was so intense so early on, it was always more important than numbers. I deeply desire that the writers I work with and the artists I am moved by find a wide audience, so that the important witness and mystery they ponder and reveal can impact more people. I believe quite literally that the arts are where we can understand what it means to be created in the image of God. Creating is a divine gift. Our imaginations are limitless, but they actually serve to play out all the possibilities and work to impart our experiences and ideas to the future and connect with people from the past. Cats and giraffes have no way of understanding the experiences of their ancestors or recording their thoughts. When we consider this fact, art indeed makes us magicians, and the more we can see, hear, absorb, consume, and share, the bigger, wider and richer life is. I hope millions of people discover our humble, heartfelt, magical collaboration. But if in this busy world and crowded marketplace, there are only a handful, then they are lucky and so are we. I am blessed beyond all measure to have this unexpected friendship with another artist arise, and to have created this beautiful project together. I hope it will bless others, too. Click here to get a copy on Amazon. Purchase an ebook copy below. If you would like a free digital copy, email [email protected] with THINKING INSIDE THE BOX in the subject line. Thinking Inside the Box- the Undrawn Art of Poet's Heart

CA$10.00

Thinking Inside the Box- the Undrawn Art of Poet's Heart is a collaboration of words by Portly Bard inspired by the 12x12" signature square artworks of Lorette C. Luzajic. It is a full colour file featuring the art, the poetry, as well as a dialogue between Portly Bard and Lorette on ekphrasis, writing, and looking at art.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|