|

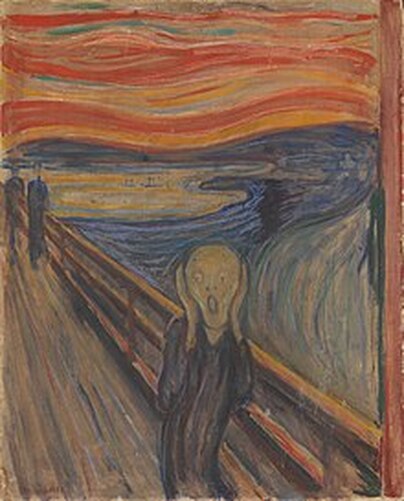

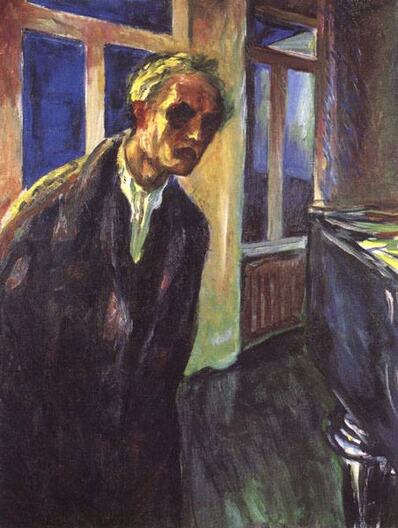

Edvard Munch: The Disease of Watching My sufferings are … indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art. I want to keep those sufferings. ― Edvard Munch Years later, he described that night, crossing the bridge at sundown. Unspeakably weary, he leaned on the rail and let his friends walk on without him. Tongues of blood and fire roiled the heavens. Earth had burst its horizon line. Something was screaming. But where in this painting is the source of the scream? Erupting from the distorted figure gripping its gaping face? But clearly the couple on the bridge hears nothing. In the lurid hues of the blood-bruised sky? And yet, in monochrome lithographs, The Scream unsettled the parlors of Europe. In the tormented mind of an artist who now would never be anything other than the man who painted The Scream? Yes. Maybe there. Across the bottom of a later version, he penciled: Can only have been painted by a madman. But if the scream arose from his madness, how to explain us. We hear it as ours, that scream, released from the rusted hinge of time to give voice to our shattered age. Who was he that night at twenty-nine, as he set out across a bridge with his friends? And after: who was he then? It must have been awful. Like living again and again through something you did not survive the first time. There are paintings like that. Encyclopedia Britannica, first edition, 1771: If you’re looking for insomnia, you find, “The Disease of Watching.” His was a lifelong insomnia. Years of absinthe, bouts of depression, anxiety, voices, incarceration, but it was the sleeplessness that brought him to the limit of his endurance. Through all those years, Munch watched the muddy, coagulated flow of his sufferings, and he painted himself-- Self-Portrait in Hell, With Burning Cigarette, With Lyre, With Bottle of Wine, Self-Portrait Beneath Woman’s Mask, With Cod’s Head, `With Skeleton Arm— each canvas torn from his mirrored flesh like a tissue of skin to become the face of a man who no longer existed. He couldn’t paint a self- portrait fast enough to be true. At his death, there were seventy of them. More. A lifetime of faces to drag through his nights, drag like a shadow across the floorboards. Drag like a lake. Consider two: The Night Wanderer (1924): He is 61, living alone, a stooped and sour old man walking the rooms of a darkened house in the hours before dawn. His hands are not shown, deep, perhaps, in his dressing gown pockets or clasped, as the elderly do, at his back. He has tried to bury his eyes. Imagine the mind of the man who painted The Scream, shuffling night after night through this hall of mirrors, floors tipped forward, walls out of plumb, a memento mori peering from every reflective surface. His skull-like face in the polished leg of the grand piano, in the bone moon at the tall window glass, in the sheen of the floorboards, in the face on his easel, half-formed, eclipsed by two ghastly cavities, as if two thumbs had put out his eyes like candles. Each self-portrait was his last. (Each self-portrait was his last but one.) Why go on trying? After a lifetime, who among us deserves a face? Self Portrait between the Clock and the Bed (1943) A stick of a man, erect and proper in a formal coat, he stands between a clock with no hands and a narrow, neatly made bed. Paintings, his own, selected from over a thousand, hang at his back. `Everything arranged. But first, this face to master. His last. (His last but one.) How does such a man die? He died the following winter. Sleepless, he wandered into the frozen night and caught a chill. It `was, in the end, that simple. He was found in the morning shaved, fully dressed, Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot open beside him. Marjorie Stelmach This is an altered version of the original poem, with format modified for the web. Marjorie Stelmach has published six volumes of poems, most recently Walking the Mist (from Ashland Poetry Press. Her work has appeared in American Literary Review, Gettysburg Review, Hudson Review, Image, Notre Dame Review, Poet Lore, Prairie Schooner, and others.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|