|

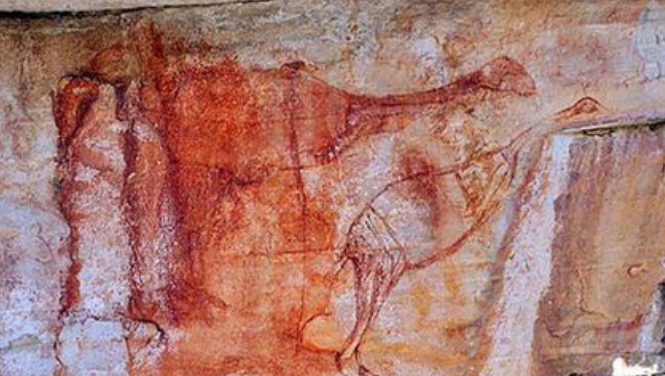

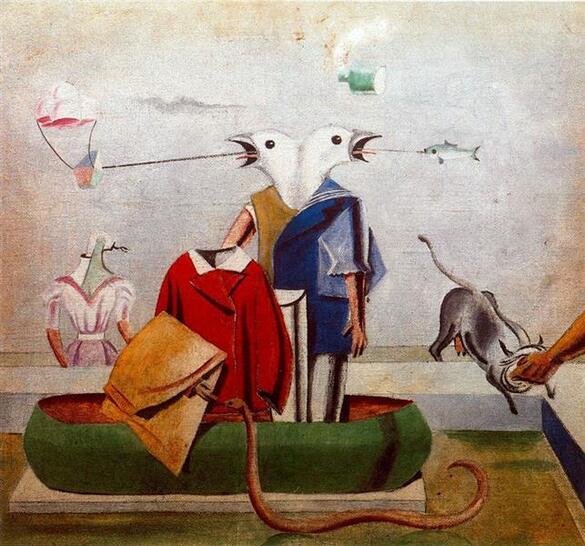

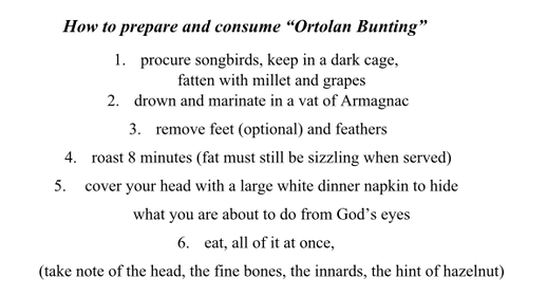

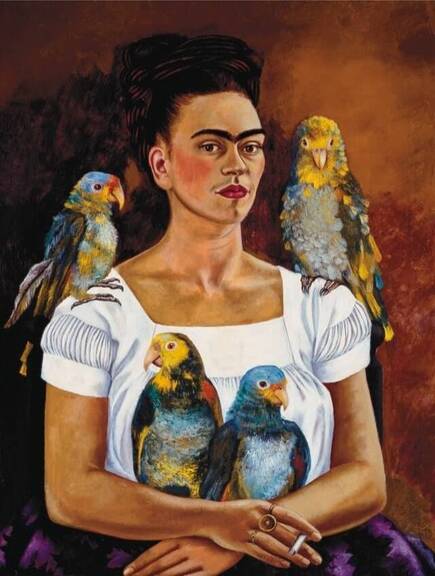

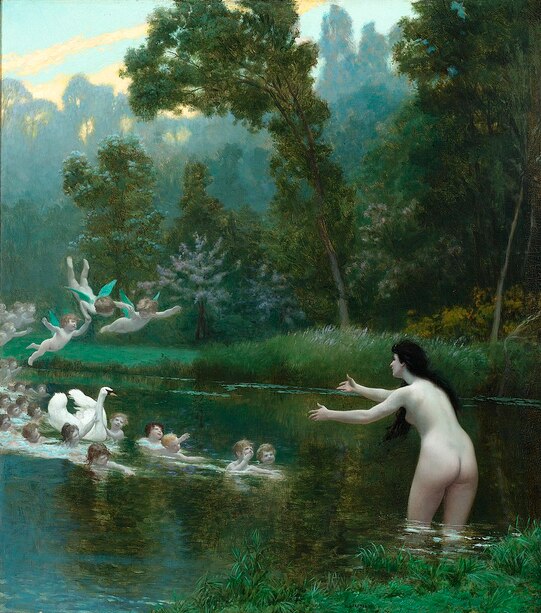

At long last, the finalists for the Bird Watching contest have been selected! There will be two posts, one for flash fiction, and one for poetry. Be sure to bookmark them both so you don't miss any. The bird theme in art is literally as old as the caves, and transcends cultures, media, and time. We are fascinated by birds: they can fly, for one thing, which makes them seem magical. We see them as richly symbolic: freedom, peace, life, death, mystery, war. We see them as messengers. The Bird Watching ebook contained forty intriguing artworks on the theme of "birds." Participants entered up to five poems or stories inspired by those works. (If you missed the contest, you can still use the curation of bird paintings and other art in your ekphrastic practice. Click here to nab yours.) Congratulations to our finalists in flash fiction and in poetry. It was incredibly difficult to choose. The Ekphrastic Review seems to attract and inspire a magnificent array of creativity. We have had a goal in recent times to attract more flash fiction writers and readers to a journal that evolved organically to be poetry-heavy. We love poetry- always have and always will- but we also hoped to bring the wonders of ekphrasis to the fiction world and let short story writers who love art discover us. There is a tradition of fine fiction inspired by art in the form of novels, some of them ultra famous (The Goldfinch, by Donna Tartt) and we wanted to find the pulse of emphasis in short fiction, too. With this goal in mind, we invited the incredible Karen Schauber to be our judge. Karen is well-known for her flash fiction: she is everywhere. She is the editor of Group of Seven Reimagined (Heritage Books), a collection of flash fiction in response to paintings by the iconic Canadian landscape artists (full disclosure: a Pushcart-nominated story by yours truly, "The Paper Dark," is inside, and I am humbled to appear alongside many Canadian literary all stars!) Karen is also the editor of the flash fiction column at The Miramichi Reader and runs Vancouver Flash Fiction on social media. She is a family therapist as well. We are very grateful to Karen for so generously sharing her time and talent with us. Her enthusiasm for art and flash and for our journal has been instrumental in getting more eyes on the work inside Ekphrastic. Karen will choose our contest winner in the flash category from the selection of finalists here. The winner will be announced by end of May, and will be published again, in The Miramichi Reader, and will be awarded a prize of $100CAD. Congratulations to our flash fiction finalists! What wonderful feats of the imagination- you have opened new doorways to art, approached the paintings from every angle and invented angles of your own. One story is just a few sentences; one incorporates the "hermit crab" style of flash fiction; some are surreal/speculative; one is a haibun; one writer landed two stories; and some flash fiction entries were bravely submitted by writers who usually send poetry. Bravo to all of you! The poetry finalists will be posted shortly! The Flash Fiction Finalists Birds, Fish, Snake, by Alan Bern Origins of Language, by Barbara Black Frida and Me, by Bonnie Lee Black If It Is a Genyornis, by Rose Mary Boehm Giant School, by Federico Escobar The Glitch, by Federico Escobar Cutting Figure, by Christina Rauh Fishburne Bird Child, by Gloria Garfunkel A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling, by Jason Gebhardt Mystical Birds, by Kendall Johnson Unfit, by Mary McCarthy Stepping on the Throat of Their Song, by Barbara Ponomareff Fly, by K.D. Prima We are grateful to each and every participant. Your ebook purchases have helped us create these cash prize contests where we can pay a winner. We have also been able to run a few social media ads, with the goal of attracting more readers. And as the Review grows and takes more and more time, your purchase and support helps accommodate that reality. Soon we will turn six and we are just getting started! We want to have many more challenges, contests, and content and we are so glad you are part of this wonderful movement. Join us for our next contest, on the theme of Women Artists. Our guest judge is Alarie Tennille! Without further adieu, here are the finalists in flash fiction. love, Lorette If it is a Genyornis 1) A genyornis is a very old bird. Resembles an Emu. And if it is one, this cave painting is old. About 40,000 years old. That’s when the genyornis disappeared from Australia. Just died out. Like the dodo. No hungry sailors reported. 2) The Chauvet Cave in France is the oldest painted cave in Europe. They dated it at 30,000 years old (Upper Paleolithic), the time that began 40,000 years ago and produced stone tools. 3) Archaeologist Ben Gunn said, "The details on this painting indicate that it was done by someone who knew that animal very well. The detail could not have been passed down through oral storytelling.” Across the road as it were, they found some cool paintings of thylacine (Tasmanian tiger), the giant echidna, and the giant kangaroo. 4) 40,000 years ago the Jawoyn people lived in this country as well as other Indigenous groups. Speculations are rife: The paintings helped the hunters. They offered them to their Gods. Perhaps it was ritualistic in other ways… why not for the love of art? 5) “I experience a period of frightening clarity in those moments when nature is so beautiful. I am no longer sure of myself, and the paintings appear as in a dream.” Vincent van Gogh Rose Mary Boehm Rose Mary Boehm is a German-born British national living and writing in Lima, Peru. Her poetry has been published widely in mostly US poetry reviews (online and print). She was twice nominated for a Pushcart. Her fourth poetry collection, THE RAIN GIRL, was published by Chaffinch Press in 2020. Want to find out more? https://www.rose-mary-boehm-poet.com/ Birds, Fish, Snake, by Max Ernst (Germany) 1921 Please be aware of the dangers Even metal objects can pose as living beings in terrible places. The letterbox with jaws clamping. No letterbox can swallow the letters...thank goodness. l envied Bobby so much; he had the freckles. And his Dad knew how to fish, taught him how. Father-son overnight at rivers end when Bobby and I were seven. I loved sleeping in the cool, slick bags. Foggy morning, early hike around. Campfired breakfast, can’t remember what. It was decades later that I asked Dad about Bobby’s father, Robert, Sr. Dad wasn’t sure what had happened to him. “And do you remember camping with them at rivers end?” I asked. Dad did. Father-son overnight. Dad still didn’t know how to fly fish, but he knew more about some fish, salmon for example, than nearly everybody. Dad loved to eat trout, but didn’t ever order salmon. “But they’re cousins,” I wondered. No response from Dad. Then Dad filled me in: Bobby’s father had been a drinker, an abusive one. “I think he probably hit Bobby,” Dad spoke softly. “Senior knew how to fly fish, but his research was weak.” My memory of that whole outing flipped. Afraid. Not of my Dad though he used to yell sometimes. Dad was a kind man. But Senior in my memory holding that fishing rod. I was scared of that. And Bobby? What had happened to him? Who knows. In a letter Rilke reminds the young poet that sadness will pass and as it passes, one can learn things. Maybe my fear was like that, a fine teacher. Alan Bern Alan Bern is a recently retired Children’s Librarian. He is a poet, storywriter, and photographer and has two books of poetry published by Fithian Press: No no the saddest (2004) and Waterwalking in Berkeley (2007). A third book of poetry, greater distance (2015), was published by his own press, Lines & Faces, a press and publisher specializing in illustrated poetry broadsides, collaborating with the artist/printer Robert Woods, linesandfaces.com. Alan was a runner up for The Raw Art Review's The John H. Kim Memorial Short Fiction Prize for his story 'The alleyway near the downtown library'; he won a medal from SouthWest Writers for his story 'The Return of the Very Fierce Wolf of Gubbio to Assisi, 1943 CE [and now, 2013 CE]'; and his poem “Boxae” was first runner-up for the Raw Art Review’s first Mirabai Prize for Poetry, 2020. Alan has poems, stories, and photos published in a wide variety of online and print publications, from which his work has been nominated for Pushcart Prizes. Recent photos include: unearthedesf.com/alan-bern, thimblelitmag.com/2020/08/10/emptying/, and pleaseseeme.com/issue-7/art/alan-bern-art-psm7/. Alan is also a performer working with the dancer Lucinda Weaver as PACES: dance & poetry fit to the space and with musicians from Composing Together, composingtogether.org. A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling She’s so pale and still against a blue that’s too deep and uniform to be the sky. The squirrel leashed to her arm. The starling leaning in to whisper the story of this blue that’s not air, but an ocean tugging continents toward each other. Jason Gebhardt Jason Gebhardt’s work has appeared widely, including in The Southern Review, Poet Lore, Iron Horse Literary Review, Crab Creek Review, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, and more. His chapbook Good Housekeeping was a semifinalist in the 2016 Frost Place Chapbook Competition and won the 2016 Cathy Smith Bowers Prize. He is the recipient of multiple Artist Fellowships awarded by the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities. Bird Child My parents and grandfather were Holocaust survivors who settled on a 100-acre poultry farm in New Jersey when I was a baby. I was raised among birds, and thought of myself as a bird child. I loved all our farm birds: chickens, ducks, and geese. They had free range to roam in the sun and large spaces. We could hear them all day and as they settled in for the night. All were well-fed and too fat to fly away, so they waddled, and when they could, ducks swam in the pond and geese floated along the current of the creek. Chickens jumped on and off the expansive chicken wire stand in the middle of the room where they could socialize and not step on their own poops that fell to the hay below. Weekend afternoons, drivers would stop and take pictures as our hundreds of white geese followed the feed wagon of our tractor in a single file, meeting it from the shady forest across the cornfield as it crossed the shallow part of the creek to the other side where their nesting boxes and food bins were located. They would settle in for the night, though the occasional fox would cause them to squawk in the dark and my grandfather would have to shoot his rifle in the air to scare the predator away. In the morning, the geese would swim or simply float back with the river current to the shade by midday. Our gravel road turned off the main paved street along the river to our house. Across the gravel road was a large pond surrounded by loose wire fencing where our ducks swam. We loved to watch them gobble up our watermelon rinds in the summer. Though our outdoor geese and ducks were too heavy to fly, they often enjoyed stretching and flapping their wings, never leaving the ground. Further up the gravel road were four large chicken coops, light airy spaces with wide windows and screens, the concrete floors and nesting boxes along the walls covered with hay. All the hay was changed frequently and used for compost for the cornfield which grew the feed that was then crushed and stored behind the barn for the farm birds. Feral cat families inhabited our barn to protect the feed from rodents, as did our two farm dogs. I still have a photograph on my wall taken by a photographer for a farm magazine. I am about three and happily holding a large rooster in my arms as I sit on a wooden fence, grasping his legs gently with one hand and wrapping my other hand around his silky wing, holding him close like a baby and smiling in the sun. I helped my grandfather during hatching season in the spring, in a separate building with a room full of fertilized eggs heated in narrow drawers of hay, watching as he pulled out the drawers, checking on progress and helping some having trouble get out of the eggs. He would warm their wet fur under heat lamps one-by-one until they were each a puffy yellow fluffball and could join the large groups of others cheeping and running around in pens under large heaters hanging from the ceiling low to the floor in the adjacent room. I also helped him use the grading machines in an adjoining building for the eggs collected twice daily by my grandfather and the farm workers, a chore I enjoyed doing as well, slipping my hand under the warm silky bellies of sitting chickens. I also loved the little birds who flew freely all over our trees and fields. From a young age, I precisely drew a variety of them with colored pencils and taped them to my bedroom walls, every kind of bird I recognized from the books I begged my mother to buy me: sparrows, starlings, robins, blue jays, cardinals, mourning doves, chickadees, mocking birds, Baltimore orioles, red-winged blackbirds, tufted titmice, goldfinches, woodpeckers, crows, hawks, and owls. I even drew the two parakeets we kept in a cage in the house, blue Peggy and green Joey. At night, I often dreamed I was a magical colorful bird child with the wing span of an angel, soaring over our farm land with a battalion of other bird children in all shapes and sizes, swooping among the nighthawks and owls, protecting our flightless birds from foxes, fierce child guardians keeping our farm birds safe at night, just like I had often wished angels had flown over the concentration camps my parents had inhabited during the Holocaust to keep them and their killed family members safe. Gloria Garfunkel Gloria Garfunkel is a retired psychotherapist near Boston with a Ph.D. in Psychology and Social Relations from Harvard University. She was a psychotherapist for 35 years, listening to others’ stories. She is now a writer of flash fiction and memoir, telling her own tales. She has published over a hundred stories in journals and is currently completing a memoir in flashes of her childhood on a farm with parents who were Holocaust survivors. She was an art history major at Barnard College as well as a painter since adolescence through much of her adulthood. Origins of Language The Creator who dashed off a bird, who snapped his fingers over the water and… Laura Kasischke, “The Accident” Was it an accident that a black word became a crow and a white word a dove? How is it possible that a Creator spoke language first and knew the names of things? Crow knew the word for “sacrificial” long before the gods were invented and even dropped sounds on rock to see what words would burst out. Later, there were whole voluptuous sentences that oozed out of an oyster shell and, with luck, a pearl as an endstop. Crow came up with articles long before that other God pointed and named. “The” was quartz grains or red ants. Shrew eyes and thistle seeds said “a” and “an.” Yes, if you want the truth, look to the birds. Doves, for example, invented the vowel sound “oo,” which has been in use ever since. Of course, being doves, they never bragged about this. Crows and doves have had a bit of a battle trying to get their vowels and consonants to work together. (Crows are the artisans who created the twig tools that were the original consonants. Don’t talk to them about how hard it is to bend a willow branch into a “c” and make it stay.) And just for the record, diphthongs were invented by the Great moaning Potoo to terrorize humans in the night. And finally, heron, with its long, particular and exacting beak, was elected to assign punctuation, done only in solitude, of course, when no one was looking on and disagreeing. So, sure, Creator by his own account “dashed off a bird,” if you want to believe that. But next time, call on the birds and they’ll give you the real story. Barbara Black Barbara Black writes fiction, flash fiction, and poetry. Her work has been published in Canadian and international magazines and anthologies, including the 2020 Bath Flash Fiction Award anthology, The Cincinnati Review, The New Quarterly, CV2, Geist and Prairie Fire. She was recently a finalist in the 2020 National Magazine Awards, nominated for the 2019 Writers’ Trust/McClelland & Stewart Journey Prize and won the 2019 Geist Annual Literal Literary Postcard Story Contest. She lives in Victoria, BC, Canada. www.barbarablack.ca, @barbarablackwriter and @bblackwrites. ** Unfit She was an acre of tinder waiting for the match, would set her hair on fire and slap it out fast, a dramatic dare and rescue the wrong side of sane. Followed by the smell of burning she marked everything she touched with fingerprints of ash. She walked the alleys for hours. Those years most drinks came in glass bottles and every one she found she swung Hard and threw against a wall to hear it smash. No one saw or stopped her and she left behind a trail of broken glass. Trees spoke to her the way they speak to the deaf, in gestures and with the shapes of shadow and light splintering the air. She knew each one she passed by its secret name, the path sap took from root to leaf, the way fog rested like a scarf around its shoulders, the way each day was a slow step in its long dance, the way they forgave her with new greens after each long winter’s freeze. She had no guardian angel but a great bird, a shadow falling like an owl, silent and dark, swift and accurate as any raptor, claw and beak and the hush of air coming down clean as a knife. Even with that fierce eye, she was more crow than owl or eagle, no diva but a canny scavenger, polishing her darks in the sun, voice a raw caw, neither the gull’s bold squack nor the long soft grief of the dove, her voice unfit for words in any language but the one she invented to speak to herself. Arms spread like wings she wore her fury like a crown, a totem, a warning, a bird whose silent scream could turn men's bones to sand, leaving her there at last a Queen, triumphant and alone Mary McCarthy Mary McCarthy is a retired RN with a lifetime love of writing and visual art. Ekphrastic work suits these interests particularly well, and has become a real favorite. Her work has appeared in many journals and anthologies, most lately in The Plague Papers, edited by Robbi Nester, and the Ekphrastic World, edited by Lorette Luzajic. Recent work has also appeared in the latest issue of Earth’s Daughters, and Silver Birch Press. She has an electronic chapbook, Things I Was Told Not to Think About, available as a free download from Praxis magazine. Mystical Birds You find yourself drawn back to the lava fields up Highway 395. Volcanic spew carved by ice rivers millennia ago, invite you to go deep. Narrow labyrinths snake through towering walls, private sanctuaries. Your bi-annual trips have turned bi-monthly and you begin to suspect ritual involved. Today monsoons are blowing up from the Sea of Cortez, and the usual dust has turned to light mud, the air heavy and rich. Desert climbs from below sea level at Death Valley on the east, to Mt. Whitney to the west. Only 70 some miles as crow flies. It’s not yet summer, so most of the tourists haven’t hatched out yet, and between weekends it’s still almost deserted. You lower yourself into a gorge, careful not to slip on water slick glacial polish. Moving south to north, a squadron of white pelicans head toward Manzanar. Kendall Johnson Kendall Johnson writes and paints in the Southern California Inland Empire. A former psychotherapist specializing in trauma, he has published several books on trauma and crisis management. He has a number of poems and stories in literary journals (including Shark Reef, Literary Hub, Cultural Weekly). His literary memoir book Chaos and Ashes (Pelekinesis Press) was released June, 2020, and his collection of flash memoir Black Box Poetics (Bamboo Needles Press) appears June, 2021. www.layeredmeaning.com Cutting Figure Breasts are meant to come in pairs. They kiss softly over a sinking heart. Jealous palms imitate their pressure in prayer. Soft seeks soft. Ridges hide. The backbone rises. The blood pumps within its cage. The ribs press, closing the gaps, reforming the space; The laces tighten; The figure is born. The eye is pleased. The breasts collide, seeking their twin. The breath rises and only rises. All is flight. All is sky. All is boundless gasp. Christina Rauh Fishburne Christina Rauh Fishburne is an American writer and artist currently living in England. Her work has appeared in Waterwheel Review, Defenestrationism.net, The Ekphrastic Review, and Perhappened, among others. She can be found at christinarauhfishburne.com. Stepping on the Throat of Their Song Clara, Antwerp, 1611 As I enter the kitchen through the waning morning dark, I enter a deep silence. When my eyes adjust, I am startled by the variety of beings and feathers heaped on the surface of the narrow table. Here, the intact head of a waterfowl has been dropped like an anchor while its limp neck still droops like a spent rope. Over there, the heavy bulk of a pheasant’s body, slung over other bodies has been piled into a basket. How careless death makes us. That cortège of small ortolan buntings, their subtle colours from madder-rose to a pale shade of lemon, has been tightly strung along a whittled willow branch that pierces each throat. And that thrush, thrown like used glove onto a bare spot. Dead center, two plucked birds, have been pressed by broad palm on my favourite platter. Its deep cinnabar colour, toxic, yes, but so alive. Enough songbirds and fowl for making pâté and roasted ortolans. Cook will know what to do, all I know, it involves Armagnac and a large white dinner napkin… Night still sticks like pitch to the background of the scene. A death-like finality presses in from the sides. Only the rim of the wicker basket gleams in a familiar way, like the perfect perch for a bird’s claw. Perhaps that of a raptor. A sparrow hawk would work, since his prey is spread out in front of us like a menu, a statement, or a question. That hawk, the hawk of my soul, I will put him on that perch, slightly off center, his head averted from the carnage, to let his all-knowing eye focus just beyond what he did. Barbara Ponomareff Barbara Ponomareff lives in southern Ontario, Canada. By profession a child psychotherapist, she has been delighted to pursue her life-long interest in literature, art and psychology since her retirement. The first of her two published novellas dealt with a possible life of the painter J.S. Chardin. Her short stories, memoirs and poetry have appeared in various literary magazines and anthologies. At present, she is translating modern German poetry. Frida and Me Your face, Frida, is everywhere around here. On just one stroll through the local mercado de artesanías on a sweltering Mexican afternoon recently, I saw your image on jewelry, jewelry boxes, face masks, key chains, change purses, back packs, T-shirts, blouses, swim suits, shopping bags, notebooks, fridge magnets, postcards, and of course in picture frames. Your popularity appears to rival that of the Virgin of Guadalupe, Mexico’s beloved patron saint. I fear, though, you’ve become a cliché, and I doubt you’d like that much. What is it about you, Frida, that has captivated this country and has driven manufacturers to make so many souvenirs with your image painted on them for tourists to take back to their respective countries as mementos? Might you be the face of female Mexico? There’s you smiling, you frowning; you with flowers in your hair, with monkeys on your shoulder; wearing an embroidered huipil in vivid colors like a young girl, wearing a rebozo wrapped around your torso like an old woman. There’s your trademark unibrow like a tarp over your eyes. In some of these souvenirs you look vulnerable, as if sleeping; in others you stare at the viewer like a dare. Are all of these self-portraits? Did you ever tire of painting yourself? What were you really like, I sometimes wonder. If I had lived in your time and place, could we have become friends? Honestly, I doubt it. I study these images of you in the many small stalls at the mercado, and I see little that might connect us, other than our shared gender. But this portrait, this one with the parrots, is unlike all the others I’ve seen of you. It is mesmerizing, and flooding me with memories. At last, I can see we have one more thing in common, querida Frida: a love of parrots. I had a Senegal parrot once in Africa who lived in a large, globe-shaped wicker cage tucked in the crook of the central branches of a young mango tree directly in front of my study window in the front of my small, cement-block home in Mali. I named him Irwin, after the American missionaries who bequeathed him to me when they left the country. If it’s possible to love a bird the same way we women are capable of loving a puppy or a kitten – delightedly -- that’s the way I loved Irwin. Somehow, Frida, I think you would understand. Irwin, with his gray, characteristic curved beak and yellow-rimmed, beadlike eyes, was the same pale green colour, tapered, oblong shape, and roughly eight-inch length as a young mango leaf. So he was perfectly camouflaged in the mango tree. In fact, to make him happy, I tied together several of the branches of the nearby mango trees to his tree, so he could stroll along this aerial walkway when I let him out of his cage during the day, in lieu of flying. The missionaries had -- cruelly, I thought -- clipped his wings to prevent him from flying away when he lived with them. But whatever bitterness and resentment he had harbored toward them for doing this, he promptly forgot soon after coming to live with me. His daily strolls – more like military struts – from mango tree to mango tree seemed to delight him. He whistled, chortled, laughed and sang what sounded like freedom songs as he swaggered among the high branches. Some of the words to these distinctive, squawky songs seemed to be, “Look at me! I am beautiful! I am FREE! I’m no longer in a cage! I can do as I please all day!” Ah, is that it, Frida? Did your parrots sing freedom songs to you too? I know that life had cruelly clipped you, as it has me, albeit in different ways. Could this be our common bond: that you and I loved our parrots so deeply because they knew the words to our songs? Bonnie Lee Black Bonnie Lee Black is the author of many published essays, as well as five published books: most recently, Sweet Tarts for My Sweethearts: Stories and Recipes from a Culinary Career (Nighthawk Press 2020); an historical novel, Jamie’s Muse, based on the lives of her Scottish great-grandparents who emigrated to South Africa in the late 19th century; and three memoirs about her own life-changing experiences in various countries in Africa (www.bonnieleeblack.com). Bonnie is an honours graduate of the writing program at Columbia University in New York and holds an MFA from Antioch University in Los Angeles. She taught English and Creative Writing at the University of New Mexico’s Taos branch for ten years. Now retired and living in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, she writes an award-winning weekly blog called The WOW Factor: Words of Wisdom from Wise Older Women, which is read by hundreds of (mostly) women worldwide (www.bonnieleeblack.com/blog/). Giant School Party day at Giant School! The bybees crawled as they sucked on sequoias and grown-ups laughed while the widgies in the school’s exhibit snuck around tunnels with teeny stone hammers to chip off flakes of gold. When Liath burped and the widgies ran for cover, oh, it was the funniest thing in the world, the funniest thing in the world. The thing with funny is it doesn’t last. This time, Moonth the Younger One started talking rivers again. “If it were a piece of string, I wouldn’t drop it on the ground like that, all curled up, eh? I’m just saying.” He stroked his beard, tilted his head, put a finger at the source of the river, which sent the water gushing in all directions, and pointed another finger at the mouth of the river. “It’s just—I would tie it in a straight line, from start to finish, eh? Wouldn’t you?” He looked at everyone and everyone looked at their shoes. Everyone except Moonth the Elder But Less Elder, who never got it, like the time with the shark-whale race that ended up sinking that widgy city called Miami. “You’re right,” he said, to the sound of thirty giants slapping their foreheads at the same time, “that bend here doesn’t need to be so bendy.” They both got up, trundled to the river, and tried to grab it to straighten it out. Dead fishy things sprinkled the land and tiny river rocks became tinier river rocks, but the river was still there. They scooped and they pulled and they splashed—still there. Then, Moonth the Elder slapped them both on the back of the head. “You can’t squeeze a river, boys,” Moonth the Elder said. “You blow it.” He kneeled and blew at the river until there were waves and Moonth-spit bubbles and more waves. Thirty giant eyes did a giant eye roll at the same time. And that was that for Wylla the Wise, who got up and gave one of the Wylla Words of Wisdom speeches that every giant nods to and wonders why they even send their bybee giants to Giant School, if Wylla has all those wisy wisdom things to say without sitting in a classroom. One of the bybees tried to listen to the whole speech, really did, but something moved across the sky and this bybee followed the shiny little flying thing and crawled over a mountain and rolled into a canyon and next thing you know she saw the flying thing’s shadow flickering over a big group of widgies, a for-real big group of widgies, listening to a handful of widgies stroking teeny metal things on their chests while the bigger group jumped and yelled and waved and something. The bybee promised herself to stay on her own side of the hill and leave the widgies where they were, doing their group thing, but the itty eagle spun in the air and came back the way it had come, and the bybee kept looking at the eagle, thinking, gosh, you could be so much more, so much faster. The thought dragged her out the hills and she caught the slowpoke bird in the air, and as the bird squawked and spun and squawked and spun, eagle feathers danced in the air like flecks of wood after stomping on a forest. The bybee was about to throw the bird forward, but there was something Wylla said, something about making peace with the times and spaces of things, because not everyone can be brilliant and funny and gianty, so the bybee thought of the perfect thing—the blue lace of peace. She untied it from her wrist—untied it from her own wrist, imagine that coming from a giant, it says it all—and took the squawky eagle and tied the lace the softest of ways, around the eagle’s ankles, for it to fly off over the widgies and make the blue lace of peace dance over all of them—imagine that, the incredibleness of that. When the bybee looked up, the widgies were gone, scared by gosh-knows-what. The bybee checked behind her, maybe the B’moth had crawled up from the sea or something, but no, just her, in her party-day-at-Giant-School dress, and the widgies were leaving a trail of tiny little shoes and tiny little meals—or poop, you never know with widgies—as they got into playthingy cars outside. Gosh, the bybee said, talking to the bird that didn’t seem to be in the mood to talk. What is wrong with them? And funny, in a not that funny way, this is the same thing the bybee said, years later, when she wasn’t a bybee anymore, and the widgies came at them, with flying things made of putty yanked from the earth and packed into hard and shiny shapes, and these flying things shot tiny flying things that nipped their way into the Moonths and turned into burning things inside them and the Moonths themselves turned into volcanoes for a minute and into stone seconds later, same with Liath, same with Wylla, and just a few of us escaped, scattered, we went as deep and far as we could, and the bybee that was no longer a bybee, the bybee that is me now, with a bybee of my own, a bybee of my own that became a stone bybee after it was stung by the widgy’s burning things, and in this inside-the-mountain darkness I rock the stone in my arms and find the water I can feel and not see, and I tell myself the stone is moving, not the creek, moving toward its own party day at the Giant School, with the bybees and the grown-ups and the laughing, and I try to squeeze the water and remember what she said, what Wylla said, that day, about the river and life and time and space, but my hands turn up wet and the stone turns up still. Federico Escobar Federico Escobar grew up in Cali, Colombia, and after living in New Orleans, Oxford, and Jerusalem, spent most of the past decade in Puerto Rico—Hurricane María included. He has published short stories and poems, as well as academic articles and translations, in both Spanish and English. His literary work has been published or is forthcoming in The Phare, Bending Genres, Passengers Journal, Typishly, Tulane Review, HermanoCerdo, Revista Eñe, and Stone’s Throw Magazine. A book of his memories as a widowed parent of a three-year-old is being considered by a publisher in Colombia. He currently works in education. The Glitch Roge looks at Pilar as he turns the doorknob halfway. His lip trembles. His hand stops and retreats into his pockets. “What?” she says. “I can’t take another baboon.” He holds his own elbows, shivering. “I really can’t.” “I can open it,” I say, and take a step forward, but it barely gets them to glance over their shoulder. “Look,” Roge says, and he lifts his shirt just enough to show her the purple pulped on his stomach. Another cold gust and his shivering gets worse. “Yes,” she says. “But it could be him this time, behind that door.” “Him or a baboon. Or an effing snake again.” “You know we have to,” she says. “What I know is I would’ve given up ages ago. Pretended the Glitch is what’s real. Lived with it.” “Yeah, yeah, you would’ve forgotten there was anything before the Glitch.” She sighed at his frown. “You’ve said this a dozen times at least.” “I have? Me?” “At least a dozen. So,” hands on her hips, “are you opening it or not? Come on, it’s the first door we’ve seen since the swamp.” His hand is perched on the doorknob again. “What if,” he says, “we’ve seen him before and not recognized him? Maybe he was the alligator from the bog. Maybe he was the lava that poured out of the door in the desert. Or maybe, just maybe—” “He was in the emptiness of the door up in the mountains? You were going to say that for the, I don’t know, fiftieth time, weren’t you?” He crosses his arms over his chest. “Matter of fact, I wasn’t.” “Look, hon, Roge, dear. This has been hard for me too. The Glitch cracked up my world too, remember? I also see numbers floating at the edge of my vision, gray squiggles threading themselves into everything, splashes of color that weren’t there before.” “Here comes the ‘but.’ Here comes Pilar’s open-the-door-anyway argument.” “He’s our son, Roge. Of course we’d recognize him. He wouldn’t be a baboon or an alligator—” “Or a dinosaur,” he says. “Or a dinosaur. He wouldn’t be that, not to us. Some things are beyond the Glitch, things not even the Glitch can touch. Like us.” “But Ginger’s eyes, remember that? As she came at us that morning, with the fangs and the claws and, and, so strong, at us, who raised her and—” She wraps her arms around him, digs her head into his chest. He breathes in her hair and strokes it until his fingers get caught in a knot. He swats at something with his free hand, swats and swats and swats, until she notices it, steps back, and holds him steady with her hands on his cheeks. “Let’s open it, dear,” she says. He gives her a slant smile, puts his hand on the handle, and turns. The hinges whine until a song takes over, the song of a black bird with red wings perched on a branch that isn’t there. “The beauty,” he says, “the beauty of the song.” “Do you know that song?” “Of course. You don’t? It played at our wedding.” He whistles to the rhythm of the bird’s song, spinning his body back and forth. “Oh my God!” She lifts her head, closes her eyes. “I do remember. And that bird. I remember it, too. Used to feed birds like that with Papa, by the lake, under a sun as bright as the one beyond that door, a sun that doubled on the water as it sank into the mountains.” He is still spinning, just outside the door, while the bird sings, without pause, without mercy. “This is it,” she says. “He has to be inside there, Roge.” “Who?” “Our son, dear. In there.” “Oh yes, of course,” he says. “The sun.” “It’s just so—beautiful. Right, Roge? So—real. Come.” She takes his hand. “Want to come with me? In there?” His head swings left and right, to the ups and downs of the song. He lets himself be steered inside, until the yellow engulfs them. The creaking of the door drowns out the song. I think of screaming, of ramming my foot inside and yanking them back here. No point. Inside or out, the Glitch has them. The door clicks closed. I open it and a fire burns inside, a fire in the middle of a cricketed prairie, dancing over the logs that ashen as they nourish it. No bird, no yellow, no song. They are gone. And they were wrong, about recognizing their son. I watched them from the start, following them from door to door, from swamp to desert to forest to tundra, as they searched. I talked to them and they kept looking. I got in their way and they kept looking, as sure of my absence as I was sure of their presence. They looked at the Glitch so long they ended up looking for the Glitch. They were wrong, though. They never recognized me. Federico Escobar Federico Escobar grew up in Cali, Colombia, and after living in New Orleans, Oxford, and Jerusalem, spent most of the past decade in Puerto Rico—Hurricane María included. He has published short stories and poems, as well as academic articles and translations, in both Spanish and English. His literary work has been published or is forthcoming in The Phare, Bending Genres, Passengers Journal, Typishly, Tulane Review, HermanoCerdo, Revista Eñe, and Stone’s Throw Magazine. A book of his memories as a widowed parent of a three-year-old is being considered by a publisher in Colombia. He currently works in education.

Fly Six year-old Mikey and his best friend Arturo tumbled into the kitchen. Behind them, the door slammed so hard the top screen popped out of its frame and clattered onto the stoop outside. Susan jumped at the noise. She turned from the sink, dish towel in hand. “Michael Christopher Caldwell! How many times do I have to –” Seeing her son’s expression, she gasped. “Honey, what is it?” A fat tear slid down Mikey’s cheek and dripped off his chin. He lowered his eyes to the floor, his dark sweaty curls as tangled as a bird’s nest. Arturo assumed a similar posture, offering up the crown of his head, shaved bald from his recent summer buzz cut. The boys stood, mute but heaving for breath, shoulders slumped, hands clasped in front of them, like criminals awaiting sentencing. Susan dropped to her knees. She reached out and gingerly patted Mikey’s arms and legs, her hands grazing over scratches and scabs. “You’re not bleeding. Nothing’s broken, thank goodness.” She placed her finger under his chin and tilted his face up, swiping the dirt away with her dishtowel. “All right, Mikey, what happened?” He twisted away and shook his head. “Arty?” The boy looked up, blinked, then lowered his eyes and shrugged. Susan stood, planted her hands on her hips, and raised her voice. “Well, somebody had better start talking. Right now!” Arturo draped his arm around Mikey’s shoulders and nudged him. “Go on, Mikey, tell her.” Mikey hazarded a side-ways glance at Susan. She nodded encouragingly. “I, I . . .” he began, biting his lower lip to stop its quivering. He swallowed a gob of air, then vomited a rush of words. “I – I killed them! All of them, all of the babies! But I didn’t mean to, honest. Now I’m a murderer, and I’ll be a murderer for the rest of my life as long as I live!” Mikey’s face crumbled. He collapsed in a heap, his body wracked with sobs. Susan again sank to the floor. “Oh, honey – Arty, what’s he talking about?” Arturo sighed heavily. “It’s like this, Miz Caldwell, we found a blue egg under a tree. Just lying in the dirt where the roots are. Figured it fell outta a nest, and so Mikey put the egg in his pocket and climbed up the tree and real careful put the egg back. We thought we’d saved her, saved the baby bird! Until that shithead Billy Barber – ooh, sorry, Miz Caldwell – came along. He said now the whole nest smells like humans, and now . . .” Arturo wiped his eyes. “The mother’s gonna abandon the eggs and . . . all the baby birds, even the one we saved, are gonna die and Mikey killed them all.” Arturo’s voice faltered. “I see. Thank you, Arty. Run along home now, honey. Mikey’ll come out to play later.” “Uh, okay. See ya, Mikey!” Arty said, flinging himself through the door. Susan drew Mikey onto her lap and rocked slowly. His head rested heavily on her chest. He clenched her shirt in both fists as if he were holding onto the side of a cliff. His breath came in shivery sighs, wet lashes like spider’s legs brushing his cheek. “I didn’t mean it, Mommy, I didn’t. But I killed the eggs and now I’m bad. Will you still love me even if . . . even if . . .” Susan caught her breath. Voices from her childhood rang in her ears: stupid, fat, ugly. Then Mikey’s father’s voice, louder: lazy, worthless, bitch. “I’ll always love you, no matter what,” she said. “But you’re not bad. You didn’t kill the baby birds. The mother won’t smell you.” “She won’t?” A hopeful note crept into his voice. “But Billy said –” He wriggled around in her lap so that they were face-to-face. “Billy’s wrong. I’m your mom, and I know something Billy doesn’t know. Little boys don’t smell like humans.” Mikey’s mouth dropped open. “They don’t? What do they smell like?” Her heart exploded for love of him. She smiled and traced his cheek with her finger. “Cookies and dirt. Little boys smell like cookies and dirt.” His face beamed as if he’d swallowed the stars. Jumping up, he ran to the kitchen door and jerked it open. “I gotta go find Arty!” Susan stood, and from the kitchen window watched her son tearing across the backyard. He turned and waved, and when she raised her arm and gestured back, her sleeve slipped down to her elbow, exposing the thin red lines carved into the flesh of her forearm. For several seconds, she contemplated the scars, parallel and neat, like railroad tracks. Then she pulled the fabric to her wrist and shook her head. Not her son. Never her son. Life’s ugly truths could wait another day. For now, for today, he will soar. K. Di Prima K. Di Prima is a novelist and short story writer. Her work has appeared in Dream Noir, Flash Fiction Magazine, Rock and a Hard Place, Crack the Spine, the Broad River Review, Image OutWrite, and Our Happy Hours: LGBT Voices from the Gay Bars. She has written also for The Philadelphia Business Journal, The Philadelphia Lawyer, NJ Lifestyles Magazine, and others.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|