|

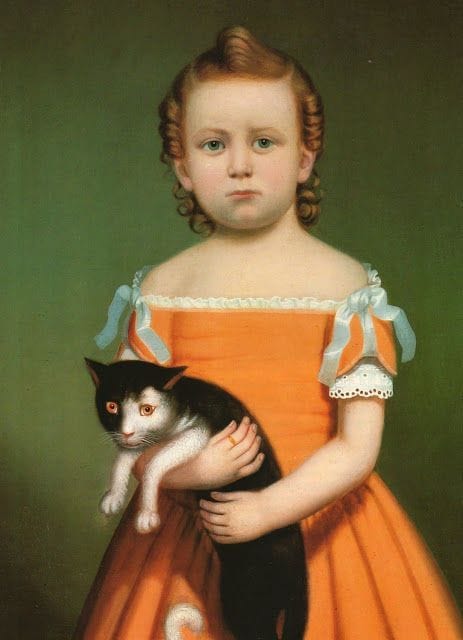

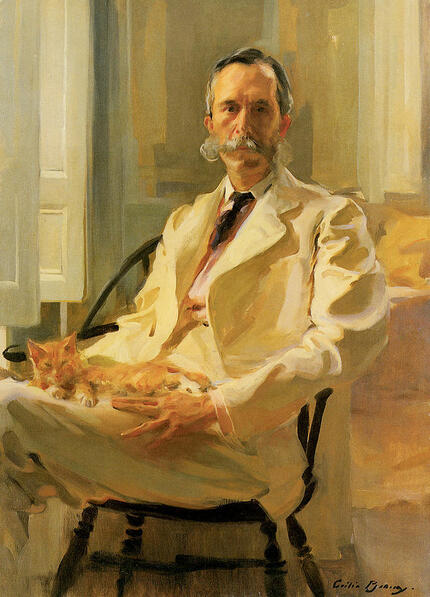

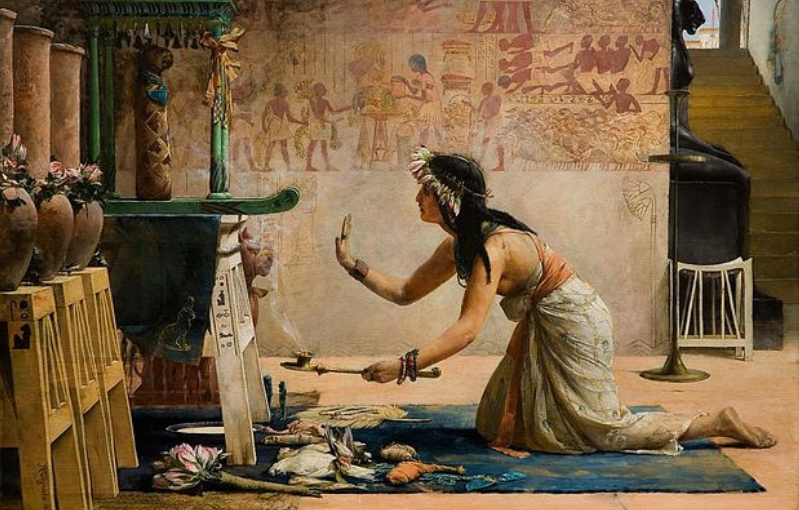

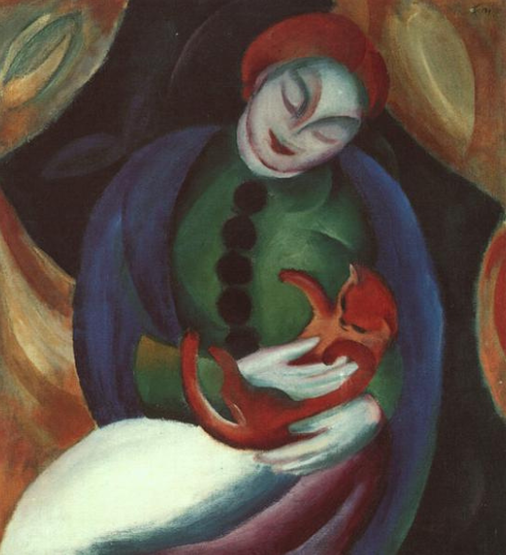

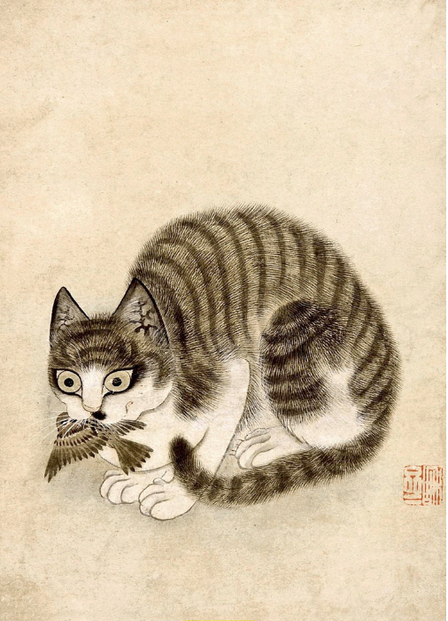

Congratulations to the authors of all of these stories that placed as finalists in our Ekphrastic Cats contest! The six finalist stories, are below, with the winning story first and the finalists in alphabetical order by author. Ekphrastic Cats Flash Fiction Finalists Orange, by Karen Crawford Bastet's Protection, by JKForward The Decision, by Nancy Ludmerer One for Sorrow, by JP Relph Treasure, by JP Relph Familiar, by Jane Salmons Ekphrastic Cats Flash Fiction winner is One for Sorrow, by JP Relph. With many thanks to our guest judge, Kathryn Kulpa. All flash fiction entries were read blind. Guest Judge's Note: When I was a kid, I thought of myself as incontrovertibly a dog person. Cats crept up on me slowly, the way cats do, with a subtle and quiet affection. Now I can't imagine living my life without them. These artworks and stories capture the elusive charm and changeable nature of cats: they are mystical, even godlike; mischievous and funny; fierce hunters; loving companions; beings that, as the legendary familiars of witches, seem to have a bit of magic about them, an ability to slip between worlds. The winning story, "One for Sorrow," captures this otherworldly quality in the black-and-white cat Magpie who helps two children dealing with crushing grief. Magpie appears when he is most needed, but leaves the narrator wondering if "he was ever our cat, or a cat at all, really." Some of the stories, like the heartbreaking "The Decision," focus on the human-cat bond; others, like "The Treasure," show us the world from a cat's point of view. I found something to admire in all of them, and choosing the winner and finalists was a true challenge--like choosing a favourite from a litter of kittens! Kathryn Kulpa You can read the poetry finalists for Ekphrastic Cats here. One For Sorrow Summer could have passed in tortured silence but for the orange girl and the cat. I was on my bike, going nowhere, wheels held by grabbing weeds. A lawn battled somewhere beneath me; memories of football and cricket matches in the roots, the scars of two boys’ pounding feet on bruised blades. I kept my eyes firmly away from the only shuttered window – my brother Nathan in bed, dead-but-not-dead – saw the girl burst from the house next door. Everything about her bright, my eyes wrenched from tangled green, only to see my misery mirrored in her face. # When the doctor said Nathan was “in a coma”, I heard Dad whisper vegetable and I laughed. Dad dragged me from the room, slammed me into a sticky-plastic chair. I wanted to say I’d remembered Nathan sneaking veggies to the dog under the table. How the dog always farted something awful and Mum didn’t know why. I didn’t say. Dad’s face was hardening like concrete, impenetrable. A nurse brought me orange squash but it tasted sour in my mouth. # Clementina – who preferred Tina – had been forced to live with her grandparents: tiny, iron-haired prunes who seemed improbable caregivers. They’d glower and grumble when Nathan and I played outside, scuttle between immaculate flowerbeds like silverfish in matching cardigans. Tina had brought only important things with her, her grandparents despising “clutter”. Favoured books, science posters, a pumpkin-coloured bike, and her cat. A solemn-faced monochrome moggie called Magpie, he’d turned up the night after the funeral, winding round her black tights as she clung to the steps of a house with a For Sale sign already dug in. Tina made him a collar from orange ribbon and his generous purr would later soothe her to sleep in a stripped-bare bedroom, pearls of cream bobbing on his whiskers. # When the firemen pulled Nathan from the water, his hair tar-black against his blue-blushed face, I believed he was dead. I was wrapped in silver foil, scrunched in the back of a Police car, trying to hold my bones still. Swirling lights jewelled the lake ice, making onyx of the black maw that had swallowed Nathan, frigid teeth biting. I’d slid on my belly, gripping his hand until mine purpled and numbed and he slipped like a fish and my screams were white feathers. # Tina and I favoured the woods, the lake’s shady side, the churchyard. We wanted concealment, escape from the sun’s brand. Magpie followed, equally content with chilled places, the numbing quiet of trees and stones. Tina always wore orange; russet dungarees, satsuma dresses. An apricot swimsuit when we ventured into the shadow-darkled water, Tina leading me like a skittish pony. Her hair looked like cheese curls, pulled into brutal bunches that made almonds of her hazel eyes. She said the happiness of all the orange hid the grey inside her. I imagined her crying topaz tears into velvet-black fur. Wished I could. # Preoccupied with bed-baths and herbaceous borders, nobody noticed us straying. We ate too much cereal, didn’t brush our teeth, stayed out beyond dark. We were wraiths finding substance in our connection. Lying on a mattress of spongy moss and sweet violets, staring through the dark-green canopy with just a peek of painful blue, Tina took my hand. Her cheeks had flushed, were striped with escaped curls that were red as the autumn to come. Our smiles were light as woodland moths, but our chests felt unbearably heavy, crushed. # One morning Tina was waiting on my doorstep, arms around an urn in her lap. Magpie’s tail enwrapped one wrist – a brilliant-white bracelet on a carnelian sleeve. His pale eyes, like shelled pistachios, blinked slowly up at me. I nodded. We got a train to the coast, drank colas and watched the landscape change. Magpie coiled next to me, tail flicking at distant birds. Tina opposite, hazel eyes staring at nothing but her own pale reflection, marigold trainers resting on my knees. It was cold by the water; I was grateful for Magpie’s heat against my chest. Tina waded into the thrashing wavelets, upturned the urn and a sea-wind took her mother away. We walked the sand, huddled together, followed wheeling gulls to a chip shop. On the train home, Magpie snoozed between us, snores strident with cod flesh, and Tina pressed her salty ginger curls into my shoulder. I went to bed feeling empty and full at the same time. Stared at the wall separating me and my brother. # We were tidying my garden, pulling weeds with green-striped hands, Magpie chasing midges with kitten-like abandon, when I found the Spiderman toy. I picked it up, wiped it on my jeans. It was Nathan’s. Perhaps abandoned on that cold day we’d been bored and snuck to the lake. I looked up at the shutters, my whole body shaking until Tina wrapped her arms around me and I absorbed her orange warmth. Magpie walked to the house, looked over his shoulder and meowed loudly. Tina gave me a gentle kiss on the cheek. The beautiful burn of it lingered all the way upstairs and into my brother’s room, where I sat in the rocking chair by his bed with Magpie purring in my lap, and cried and cried. My tears were ice-cold and tasted lake-dark. # Then summer was over. Tina grizzling in school-grey, cheeky orange bobbles in her plaits. In our homes a sudden peace had settled like autumn leaves. Dad ruffled my hair at breakfast. Tina’s grandma knitted her a carrot-bright scarf. We laughed more, kissed more, her warm hand now part of mine. Magpie vanished on a light-frost night; his handmade collar left on Tina’s doorstep. Although we searched for days, hearing ghosts of his meow, we knew he was really gone. He was never our cat, or even a cat, really. He hadn’t left a single black or white hair on any of our clothes. We grieved this loss together too, finding our way to joy before snow fell and covered the orange ribbon. JP Relph JP Relph is a working-class writer from North West England. Her writing journey began in 2021 with Writers HQ and is mostly hindered by four cats and aided by copious tea. A forensic science degree and a passion for microbes, insects and botany motivate her words, which can be found in Splonk, Noctivagant Press, Full House Literary, Moss Puppy Magazine and others. Twitter - @RelphJp Orange He was yours before he was mine, the rescue that lived in your office that everyone liked but nobody wanted, and when he became sick he became ours, and for a little while he was loved and for a little while so were we, in sickness and in health, in health and then more sickness, until the vet said in that gentle voice reserved for occasions just like these that it was time to let him go, and I held his tender body tight until his fur became a river and now I'm staring at his empty bed and his empty bowl and this empty house and I'm praying for a sign with a tremble in my hands because I need to believe that he's at peace and then I swear to God a flame of Orange flashes by and I follow it into the living room, and his crooked tail is weaving between my calves as soft as a down comforter and I pick him up, and his mighty paws are hugging my shoulder and his tiny nose is burrowing into my skin and you come out with morning eyes and I want to know if you can see him and you say you don't know what I am talking about, and then he jumps onto the couch and I take your hand in mine and I place it on his belly and he's radiating warmth like an electric blanket and I ask if you can feel it and you say you don't feel anything. Karen Crawford Karen Crawford currently lives in the City of Angels, where she exorcises demons one word at a time. Her work appears in A Thin Slice of Anxiety, Anti-Heroin Chic, Rejection Letters, Potato Soup Journal, among others. You can find her on twitter @KarenCrawford_ Bastet's Protection Perched in the prow of the family felucca, I felt as elegant as I knew I looked, especially as I was wearing a new jewelled collar. Down the Nile we glided. Above us, the tall and narrow triangular sail was taut in the warm morning breeze; it would luff and flap as Man tacked back and forth across the wide river, doing his best to navigate around other craft large and small. On the shore, the great pyramids were blindingly white in their limestone coats, and the rising sun rivalled their golden caps. We were wending our way to Bubastis and the festival at the temple of Bastet, Cat Goddess of protection. The Family was excited and chattering noisily as they breakfasted on partridge-filled pastries, figs and grapes. My ears turned, keeping track of Toddler as she scrabbled about behind me, a rope around her waist in case she should fall overboard. Toddler tried in vain to capture my tail as I swept it back and forth, snake-like; our favourite game. Woman approached and gently laid partridge meat before me, then collected Toddler to take her, complaining, to the stern and to leave me to eat in peace. At last, the boat nosed into the reeds at the riverbank’s edge and Man and Boy jumped into the knee-deep water, splashing me where I balanced on a gunwale. They turned quickly, apologizing, and then slowly drew the boat in so it stopped smoothly on the silty river bottom. They bowed, standing aside for me to gracefully leap ashore. I stood still on the hot dry soil, tail twitching, my senses alert. Toddler squealed behind me as Woman lowered her into the shallow water. She splashed towards me, almost hidden by the reeds, calling my name, “Cat!” But I was distracted; a movement in the sun-bleached grass had caught my eye. I crouched, hiding behind the blades, my gaze intent. Only the tip of my tail twitched slightly. Toddler saw it and rushed forward. In that moment, Cobra rose from the grass, its hood flaring, a tail’s-length from the two of us. Woman screamed, Boy bent to pick up a stone, Man leapt forward. It was I who foiled the fangs meant for the child. And I died. Today Toddler, Woman now, kneels before me where I stand erect on an altar at the Temple of Bastet, embalmed in honey and resin, wrapped crosswise in linens. The scent of incense and flowers mixes with the tones of reverence and thankfulness in her voice as she relates this oft-told Story of Me. JKForward JKForward is a writer who enjoys both reading and writing the short form. A favourite place to wander for a day is either a museum or an art-gallery where she enjoys gathering ekphrastic stories with the butterfly net of her mind. Nature also inspires her. The Decision Had I known even the gentlest creatures do not go gently, I would have done things differently. I wouldn’t have said the vet could come here while you slept on your soft new bed. I would have said no, not yet, insisting that you decide, not me. And as unreasonable as my insistence would have been, I am sure you would have done it, signing on the dotted line in your own good time and at the right time, not like me, my signature wobbly and indecipherable. And even though you had never signed a thing before, had only licked the ink of my scribblings or gripped my pen in your fangs or hid it between your paws, all things you were too weak to do that day or not inclined to do that day, you would, I am sure, have done it if you had only known how afterwards I would never get over it. You would have done it for me. Nancy Ludmerer Nancy Ludmerer's fiction and flash fiction appear in Kenyon Review, New Orleans Review, Electric Literature, Mid-American Review, Grain, and Best Small Fictions 2016 (a River Styx prizewinner). In 2020, her stories won prizes from Carve, Masters Review, Pulp Literature, and Streetlight. She lives in NYC with her husband Malcolm and their recently-adopted 13-year-old cat, Joseph. Twitter: @nludmerer Treasure Heat crackles in every grain of sand, intent on transforming the red-blonde waves into glass. The oasis of verdant shadow and chill lies far behind her now – no hint of the green scent in her nostrils, just a dry-baked rustle. Her measured steps kick up alarmed puffs as she takes a circuitous route to the building which shimmers with promise. Heat slips like molten gold down her spine, pools in the back of her neck. She longs for sleep – a sunpuddle slumber – but the sand is no place to linger. It is made living by the pounding sun: it shifts and slips around her feet as if waiting for the perfect moment to snag them, pull her under. She’s so close now, stones resolve from the heat-veil. Burnished bronze with lichen lacework, they offer shady respite, and so much more. A treasure she needs, to survive. Heat halts at a wall of shadow, as if turning from day to dawn in a step, she shivers. In the lee of the building, the sun’s relentless charge is repelled, the sand glitters silver, gives way to a ribbon of chilled pebbles. Fine hairs stand up on the back of her neck: there’s danger ahead, if she’s caught here. She must be stealthy and sure-stepped to remain undetected. There’s a hole in a door she can just slip through; mouse-like, hugging shadows. Heat is just prickling in the silent space; hot fingers reaching just one far corner at this time of day. She has learned that this is the best time: when there’s nobody to see her, catch her in the act. She can hear water dripping, smell something bright – like the ramsons in the woods. Her sharp, greengage eyes survey quickly, alight on the prize. She approaches, padding on spider-soft feet. # The boy crouches in the living room, one blue eye pressed to a narrow gap between door and frame, breath held behind a wide smile. She’s come again, seems unaware of his presence. She crosses the shade-filled kitchen to the bowl of mackerel, her ears and tail constantly twitching. Daddy moved them to this house a month ago – the cat turned up a week later, looking for something. Daddy joked she was a “cat burglar”, which confused the boy (wasn’t that someone who stole cats?), reckoned the old lady who’d lived here probably fed the cat, installed the cat-flap. Daddy also said it could be just a wily cat, skilled at marking out a good score. The old lady had also made a strange desert landscape of the garden. Children’s play-sand, fake boulders and plastic cacti all the way to the Leylandii at the bottom, beyond which is woodland. Daddy was going to get rid of the sand, make a lawn for football. The boy would miss the swirled patches where the cat had slept in the sun, the trails of cute pawprints going in all directions. He wanted a cat very much. Daddy said they could go to a shelter, but the boy wanted the shy cat. She was like him. Hanging out alone. Needing a friend. One who’d treasure her. So, he’d started leaving food out and, eventually, she came inside for it. Eating fast, darting away. Now, his knees starting to ache, the boy watches the cat eat the mushed fish. She’s small with a round face and where she isn’t dusty-white, she looks like a fluffy mackerel. He loves the moist chewing sounds she makes and the way her ringed tail wraps around her back legs. He longs to stroke her. # Heat starts to spread through the space, like golden syrup spilled. She sits for a risky moment, licking and licking, wetting her paw to clean the delightfully oily fragments shimmering on her whiskers. Her morning meal was more feather than flesh and, while she thrills with the hunt, this is infinitely tastier. There’s water too - she has a long drink before she starts her journey back through the burning sands. # The boy’s legs cramp, one foot shoots out and hits the kitchen door. # She starts, cleaning abandoned, tail an instant bristle-brush. She darts for the hole in the door. # The boy wishes she’d stay longer, whispers bye kitty as she leaps over his foot. # She stops at the hole, turns towards the human in the doorway to the rest of the building. She’s never been through there. He’s small, has a nice face; soft and kind, and she smells the fish on his fingers. # The boy breathes so slowly, his blue eyes meeting her sand-gold ones. The cat blinks, once, twice and he hears the slightest rumble in her chest. # She rubs her cheek against a grass-soil-fungus scented shoe, meows and pours through the hole like a fish from a net. # The boy feels the loss as soon as she’s gone, but he’s certain she’ll come back tomorrow. He spends the night thinking of the perfect name. # Heat crackles in every grain of sand, intent on transforming the red-blonde waves into glass. The oasis of verdant shadow and chill awaits her: the pungent tang of hedge, the duskier scent of woodland beyond. She’s fast across the baked sand, no longer concerned with stealth. Her belly full; she has sleep on her mind. Glancing back; the boy’s face is at the window. She recalls another face that once watched her. A brown, crinkled face. Later, a warm blanket in a cardboard box when it rained or snowed; a sliver of salmon to tempt her further inside. Then it was all gone and many strange people came and went – noisy, disruptive - and she’d retreated to the relative safety of the woods. She sees the boy waving; he’s the new keeper of the treasure. Summer is going to end and she does wonder about what’s beyond the shady space. With the promise of tomorrow’s oil-slick meal on her tongue, she passes from sand to coniferous shade, scattering sparrows. JP Relph JP Relph is a working-class writer from North West England. Her writing journey began in 2021 with Writers HQ and is mostly hindered by four cats and aided by copious tea. A forensic science degree and a passion for microbes, insects and botany motivate her words, which can be found in Splonk, Noctivagant Press, Full House Literary, Moss Puppy Magazine and others. Twitter - @RelphJp Familiar Through the trees, she hears them creeping, snapping twigs under hobnail boots, the creak of lanterns swinging. She hears their treacherous curses find the slattern, damn the imp, burn the hag. Still as death, she rootles to the earth. To calm his mewls, she clutches Willow to her chest, strokes his fur, whispers shush, my loyal friend. Her mud-caked petticoats remind her of the dried up well, the blackened hearth, her husband spitting bile. Her throat is as parched as rotten bark, her hunger stings like nettles but still she hides within the woods, the voices getting louder. They say she vomited pebbles as large as eggs, suckled a grimalkin at her teat, struck dead a herd of cows with elf-bolt. Their gurning faces float before her eyes, she smells their rancid breath. The physician’s words ring in her ears, her womb is restless; she harbours melancholia. As twilight falls, Willow’s eyes flash from glittering green to demon red, a murder of crows swarms the sky and on the soles of her feet, she feels the lick of flames, the crackling peat, the rising heat. Jane Salmons Jane Salmons is the author of the poetry collection The Quiet Spy, just released from Pindrop Press. She writes and publishes poetry and microfiction, studies and teaches in England, and creates handmade collages.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|