|

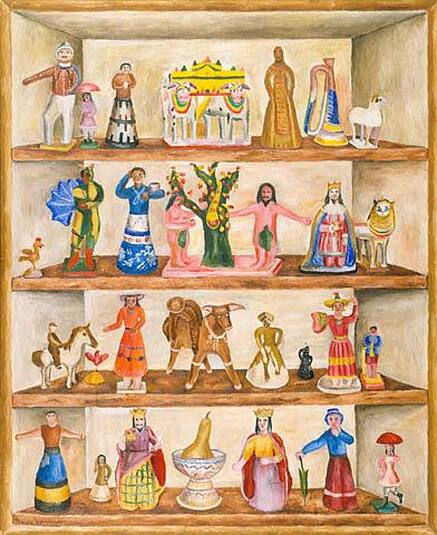

repository asking and asking of what you have collected, tried to bind-- things and things and things-- but not the living-- of those you ask nothing, especially not the invisible creations of believing, of faith-- better to ask the table, the chair, the hoard in your cupboard—the casts of dead saints-- to complete the life you have yet to find-- pray to the relics you have amassed and annotated-- an anxious arsenal of need, compulsion, and unfilled desire Kerfe Roig A resident of New York City, Kerfe Roig enjoys transforming words and images into something new. Follow her explorations on her blogs, https://methodtwomadness.wordpress.com/ (which she does with her friend Nina), and https://kblog.blog/, and see more of her work on her website http://kerferoig.com/ ** Instead of the beach we go see Mrs. Joy who’s nearly 90 and lives alone in a Victorian house, shaded by huge magnolias. On the short drive, Mama tells me Mrs. Joy is a character who still climbs out on her roof to clean her gutters. Truth be told, Mama is a character, too. The hall so quiet and dark against the summer day – Persian rugs swallow the sound of footfalls. Tick-tock, tick-tock from the Grandfather clock in the hall until we don’t notice any more. Mrs. Joy also has a spinet like the one Thomas Jefferson owned, but it stays quiet like her other furniture. She says the tour guide at Monticello told her group there were only two others like it in the world and didn’t believe she had one. I stay tuned to their conversation though I don’t always get it. “Little pitchers have big ears,” says Mama. She says that a lot, but never explains it. I can smell a pie that’s almost done. Till then, I stand with arms clasped behind my back – like I’m in a china shop, even though all the treasures here are safe behind glass. Right at eye level – close enough for even me to see. I marvel at the iridescent tea cups – so much like shells I find at the beach, the tiny fingers of the woman dancing a minuet, the stiff ruffles that look as sharp as coral. Fairies, angels, and animals are the best! I almost forget about the pie. Alarie Tennille Alarie Tennille was born and raised in Portsmouth, Virginia, and graduated from the University of Virginia in the first class admitting women. For Alarie, looking at art is the surest way to inspire a poem, so she’s made The Ekphrastic Review home for almost four years. She was honoured to receive one of the Fantastic Ekphrastic Awards for 2020. Alarie hopes you’ll check out her poetry books on the Ekphrastic Book Shelf and visit her at alariepoet.com. ** La Alacena, 1942 I begin here, Maria Izquierdo, on the left, towards the upper edge of the canvas. To paint like this was not my first choice. And I had done my homework. Critiques, reviews, historical analysis, biographical notes. I read them all. But I could not find you! A glimpse and then gone. Fallen between the ‘isms’ of real and surreal, modern and primitive. Between politics and poetry, Rivera and Tamayo, village and world. And then your paintings. I sought you there. Autoretratto. Red shawl, white crinoline, dark eyes unflinching. But unrevealing. Or Sueno y Presentimiento, your severed head and streaming hair dangling from your hand. But why linger on darkness, demise and erasure when what I seek is your smoky mestiza rootedness, your joyous creative self? And thus I have crawled into this cupboard where it is quiet and we can be alone. La Alacena. It is your first cupboard. 1942. I have stretched my canvas. I stand before it as before a wall into which my body must lean. For your painting is large: forty-four by thirty-one inches. And your palette. I have laid it out – ochre, cadmium, all the umbers, siennas and red oxides of earth, celestial blues. A hog hair brush. Small, as your strokes are intimate, bristly. First, the cupboard, your stage-cum-votive shrine. I paint but a cursory mimesis. No glazing. No smoothing of brushstrokes to fool the eye. I place objects on shelves. And what are they? Ritual figurines of your folk Catholicism, primitive roots – peasant women, circus horse, bull and cock, a king offering you a crown. The garden, Eve reaching for the fruit, the serpent winding down. There they stand, Eve and Adam, their verdant fig leaves large as bushes. And on the bottom shelf, a holy chalice and pear – the consecration of your fertile self. But what of the how? This cabinet of curiosities so clumsily rendered. As if you were a naïve folk artist, Maria. As if you did not know how to paint. I trace your simple contours, inelegant shapes. My gestures – repetitive, rhythmic, unhurried. My brush, laden with unctuous oil, moving from hue to hue – siennas calling to alizarins, ochres echoing to azures. I scumble pink into Eve’s skin, smear umber into the flank of the bull, dab vermilion on a dancing umbrella. Limbs and bodies. I shape them as a child would – stocky, awkward, distorted. Eyes, mouth, hands – elemental. An anchoring down of base note metaphors. Hours spent. No light from the world without, no chiaroscuro, no illusion. Artefacts, mementos, sacred and profane, laid down in the rough, but singing, as if only you need hear. And what of the flatness of this space? Is it “shallow, collapsed, claustrophobic” as they say? Or is it a plunge into a well of stillness? A place removed, pigment sliding over form as across a swelling field of memory, desire. This is no baroque vanitas. No ode to ephemerality. No alter to the virgin of sorrows. No sorrow here. Rather being. Here inside your cupboard, you escaped the world as you escaped time. Here all the ‘isms’ are reconciled, all the caesuras and pain. This is not some frail palimpsest of a cupboard. It is a cupboard. It holds your paced and dreaming gestures, your slow stitching of materia and self. I have found you, Maria Izquierdo. I have found you painting, which you continued unrelentingly to do until the end of your days. Despite rejection and poverty. Despite illness and pain. Who can know your joy? Victoria LeBlanc As artist, writer and curator, Victoria LeBlanc has worked in the cultural community for over three decades. Former Director of the Visual Arts Centre and McClure Gallery (1996-2017). Curator of Westmount’s Municipal Gallery since 1998. Contributor to over 40 publications on contemporary Canadian artists. As a visual artist, she has participated in solo and group exhibitions across Canada. Her creative practice is inflected by an ekphrastic impulse, a back and forth dialogue between drawing/painting and writing, simultaneously exploring themes and images in both disciplines. In 2019, she published her first collection of poems, Hold. Forthcoming, Mudlark. ** Alacena When God came to Guadalajara A small girl recreated the scene With little figures made from clay To show her grandparents. She worked all day Pinching and shaping Until at last it was clear: Eve’s heavy breasts, Adam with fig leaves Improbably blooming Her uncle’s stubborn ox Dipping his horns To a King and Queen With a pear in a goblet. And her cousin Julia Balancing on one foot And a man in a maize skirt And a flowering cactus. All these she saw and Made with bright colours From her father’s sombrero, Displayed in a wooden fruit box To tell her story So without prejudice It is God’s own words She made. Lucie Payne Lucie is a retired Librarian who has spent the last 25 years encouraging others to write. She is finally taking her own advice and writing as much as possible. ** To Maria Izquierdo Regarding Alacena Your eyes were curtains you could close and open on your curios in cupboards where you staged the scenes enacted by your figurines amid the music silence played for endless moments you portrayed forever leaving hearts endeared to God and country you reverered not as elitist peering down from precipice of your reknown but eye to eye as one akin who saw your soul from deep within so many leaving richer earth to nurture art that you would birth. Portly Bard Portly Bard: Old man. Ekphrastic fan. Prefers to craft with sole intent of verse becoming complement... ...and by such homage being lent... ideally also compliment. ** Memories of La Maestra Filling the cupboard with groceries and second-hand dishes we chit-chat. I speak spanglish and present tense verbs in past tense matters. She giggles and corrects me with patience. We are sisters of two lands. A year of client/advocate work has back-and-forthed our roles. Both teaching, both learning, both mothers, both married and then divorced. We loomed our blanket of mutual respect through shared empathy. Holding hands, we climbed over or kicked through some of the walls she’s faced. She is a mentor of strength to me and I to her. She hands over trust like a tin milagro heart and I place it in a safe box hoping I never break it. This woman who came to find a dream and found a nightmare smiles and laughs with ease through tears. She is resilience personified. She’s carried many treasures inside her to this place. She is a deep well that is regularly seen with shallow eyes. She layers the coats I offer to shield her from cold words and then begins to sew more for others. Her sewing has much tighter stitches than mine because she is the expert within this storm. She is la maestra sharing wisdom, stories, tamales de pollo, and much more. I share positive cognitions and trauma-informed care. Her gifts are more filling. My gifts are received with an openness that gets me out of bed each day. Both of us revolutionaries in our little world. Fighting the old war of equality over machismo and power and control. I hope, wherever she is now, she still has my little piece added to her collection. Her offerings I will keep secured always. E. L. Blizzard E. L. Blizzard is an emerging writer in the US South. Recently, she has work forthcoming or published in Under the Bashō 2020 and Wales Haiku Journal. Within years and spaces of nonprofit work, most of her writing is wrapped safely in confidentiality. She’s allied herself with many resilient people and advocated on issues faced by immigrants, survivors of intimate partner violence within cis and LGBTQ+ relationships, those experiencing homelessness, and people with disabilities. ** Alacena Her house always smelled like lavender. The scent always seemed to hug you when you walked in, and lived inside of your nostrils for a few days after you left. When the sun was high, the scent seemed like a palpable entity within her home. The small house sat at the end of the street, nestled neatly in a clearing of the trees that grew in the cul de sac. The house was not visible from far away, only coming into sight if you got closer, giving the home a feeling that it would only appear to those who were looking for it. The house looked even tinier with the collection of stuff that she had managed to accumulate over the years. Floor to ceiling, every inch of wall was covered by something, whether it be a picture of unfamiliar family members, or just a small decorative item hung from a tack on the wall. I always liked her house when I was younger. She had so many things I thought it was a museum until I was five. There was a common ritual, where if I wanted to know more about an item, I would stand in front of it and stare. A couple of seconds later, her lavender scent would appear behind me and tell me its story. Every item on her walls seemed to be the holy grail of some fantastical tale of musicians looking for fame, or poets looking for something indescribable. I don’t know if any of her stories were true. A part of me thinks she just hated the idea that old people retold the same stories. She never told the same story twice. Not because she would change them, but because she had a way of making you remember what she said. Despite all the more interesting items hung on her walls, such as the knife from the amazon or the scarf from the Anatolian mountains, my favorite was always the shelf. I still remember the day I discovered it. We were playing hide and seek when I saw it. In the corner of her room was a shelf, with tiny ceramic figurines of diverse shapes and sizes displayed. She came into the room to find me sitting in front of the shelf, staring at it, entranced. Knowing what to do, she picked me up and put me on her bed. “This is my favorite,it has something that represents everyone in the family. Your grandpa got it for me when I was pregnant with your mom.” she said, her voice was soft and smooth, like the way honey drips off the end of a spoon in midair. “He also got me the first few figurines for it. He said he picked them because they reminded him of us.” she said pointing to a figurine of a man and woman standing next to a little girl with an umbrella. “How did he know mommy was going to be a girl?” I interrupted. “That’s what I said, and he said he had a feeling. I guess he was right” she smiled tenderly when she said that, like an animal showing its underbelly to someone that they trusted. She smiled in a way that hinted there was more to what she said, but did not go any deeper, and instead sent me into the other room to play. I did not understand then, but I know now that it was the smile of someone who was still grieving. Death is quiet, it waits in the recesses of our memories, moving into places of our subconscious we have almost forgotten about, knowing that one day we would return to them and find that they looked nothing like they did since we were there last. Two months ago, she died. I’m 20 now and still remember every story she told as we packed up her things. I’d walk in her bedroom every day, and look at the shelf, and wait for her to come up behind me, and tell me a story. A bull for cousin Sam who moved to Spain, a trumpet player for Auntie Mel that played in the Philharmonic, a little girl with a mushroom for me because she couldn’t wait to see what I’d grow into. But the stories were over, the walls were empty, and the last place she existed was in a ceramic figurine of a woman. The hardest part of grieving is imagining the world without them in it, which is a fact that seems more made up than any story she ever told me. However, sometimes, when the sun is high, for a fleeting second, I smell lavender again, and I am sitting on her bed, looking at the sky, waiting for her to tell me what it means. Stevie Voss Stevie Voss is an emerging writing from Manchester Township, New Jersey. He is an education major at Mercer County Community College and is looking forward to transferring next fall. He is currently working on completing his first novel and getting his first published poem. ** Hers and Mine The little terracottas are new to the cabinet. “Meet your new friends,” I say to Mom’s china ladies holding court on the shelves. She loved her collectibles—pale, fine-featured belles from a Victorian London ball, manor house beauties holding hats and petticoats against romantic winds. “I’m English too,” Mom told them, forgetting to mention the Gypsy part. I doubt that our ancestors had complexions as porcelain, or noses so narrow and perfectly upturned. The newcomers came from a yard sale. Handmade from chunky brown clay, maybe from Mexico or Spain, according to the seller. As unfamiliar as my roots—Mom didn’t leave me much, just her china—I bought them. They spoke to me. But will hers and mine get along? There’s an awkward silence in the cabinet. Finally, I hear a delicate voice. Wrapped in a scarlet robe tipped with ermine, “Christmas Morn” wishes everyone all the best of the festive season that, for her, never ends. On the first shelf, an earthy little soldier in a tunic with gold buttons tips his beret. “Feliz Navidad,” he says. Such a gentleman. Wish I knew his name. The ice now broken, Mom’s “Elizabeth” comes alive in her swirling white gown and long gloves. Her expression frozen (supposedly hand-painted), the figurine complements the dish with a pear I’ve set beside her. “So bright and cheerful and rustic. A perfect gift for a faithful cook. Upon her retirement, perhaps.” And oh, what a charming little horn. “Do you play?” the lady asks a simple brown rider on a simple horse on the third shelf. Neither answer. They shrug, confused. “Annabelle” is wide-eyed at a pink pair in tiny fig leaves. I fear the little girl may drop her basket of flowers. “Adán y Eva,” the terracotta couple says to her. They point to their biblical tree. “Adán y Eva!” Alas, the two collections speak different languages as Mom and I did. Karen Walker Karen writes in Ontario, Canada. Her work has appeared in or is forthcoming in Reflex Fiction, Sunspot Lit, Defenestration, Funny Pearls, Unstamatic, Commuterlit, Blank Spaces, and others. ** Cupboard Reveals All Born and seasoned at a Monterrey lumberyard outside downtown, yet close to my roots deep in the heart of netleaf white oak. Bought by a carpenter from inside city limits - a craftsman, an artisan. Thinning grey hair, blue denim dungarees. He sawed through my grain with care and devotion. Sanded off my rough, for I had so much. Planed me, measured me, mortise & tenoned my ends. Applied horse-hoof glue, assembling me at right angles to apply clear varnish - three coats. I was placed in a bric-a-brac store next a Casa de los Tacos. Lasted a day. Acquired by a Contemporáneos, a lady. Her apartamento, my residence. I stood pride of place, repository for tokens unwrapped from white paper tissue - her bone china collection: kings in regal finery, votive offerings for favor, ladies shaped by Catholicism between intangibles to subjectivity, mementos of the circus Mexicana in its glory, the horse and the sheep, a lion and a ripe pear, tree of life and a gallo, oxen pair burdened by a white cart. Remained there until ’55, encapsulated in her painting then 65 years on agonised over by a plethora of poets, ekphrastic in persuasion. Alun Robert Alun Robert is a prolific creator of lyrical verse. Of late, he has achieved success in poetry competitions and featured in international literary magazines, anthologies and on the web. He particularly enjoys ekphrastic challenges. In 2019, he was a Featured Writer of the Federation of Writers Scotland. ** The House of Mischief When I met Savannah, she was eating a golden pear with a knife and fork from an ornately painted bowl. I was on holiday in Mexico. It was Savannah who led me to Tolquin, and his house of mischief. Up until this point in my life I’d never done anything extraordinary. But I was feeling reckless. So, when Savannah suggested we go visit here uncle, I followed her, abandoning my hotel early one morning, leaving nothing behind but a note to my friends. I travelled through parts of Mexico tourists aren’t supposed to visit, stopping eventually in a village somewhere between Mexico City and a mountain. Wires below power lines were decorated with blue paper windmills. Tolquin lived outside the village. Savannah described his house as a refuge. It looked precarious, like it might just fall down, its lines were wrong, and it seemed oddly tall. The locals called it the house of mischief, and stayed away, suspicious of the various eccentrics that had made it their home. It was almost dark when we arrived. Tolquin and his companion, Marion, were in their garden. And they were naked. They were naturists, and never wore clothes while at home. Marion was coaxing an albino python out of a tree. Tolquin offered us Tequila. The following morning I had a hangover. Around midday, I got on my feet and learned that Savannah had left, gone south, said Marion, with an old boyfriend, a trumpet player. I was given fried eggs and tomatoes for lunch by a very tall woman in a long lapis blue dress. She carried a small silver urn under one arm. I was too polite to ask why, and she seemed too put out by my presence to offer her name. Her only words, muttered in Spanish, were, No prayers. God has retired. After being warned not to wander around the village, Tolquin, wearing nothing but sunglasses, suggested I stay another night or two, until his neighbour could drive me back to my hotel. Over the following two days I met, in this order, a retired wrestler who Tolquin called Charles, but everyone else referred to as the Rooster, and a Russian strong woman who kept a pet alpaca named Sebastian; there were three bearded American students, collectively known as the three kings, artists, or so they claimed. And then there was elderly Miss Laura, who was a beautiful singer; she wore a blue bonnet and carried a green umbrella. Maybe, it was the tequila, or my confusion following Savannah’s departure, but going about that house, and its garden I saw other people, and animals, that I now doubt were real. One night a man rode up to the house on the back of a bull. He was very drunk, and the bull was strangely placid. And the next night I was woken by a golden lady who was searching under my bed and muttering. I was weary and sore when Tolquin’s neighbour arrived. My driver, a small woman wearing a wide brimmed orange hat, interrogated me during our journey. She had a hard edge in her voice. She thought I was foolish, but relented. Hard words harden minds, she said. On the subject of Savannah, she explained, Savannah is a woman who always returns. You will see her again. David Belcher David Belcher is aged over 50, he lives on the north coast of Wales, and his most recent work has appeared in The Ekphrastic Review, Ink Sweat and Tears and Right Hand Pointing. David reads and writes poetry for enjoyment, and because he can feel it doing interesting things to his brain. ** Altars Day of the Dead approaches. The sun lowers in the sky. Even when I tie old sheets between posts on the back porch under the awning, I cannot get the sun out of my eyes. I move inside behind the floor to ceiling glass door with metal grillwork so no one can break through. That’s not the case with the spirits of those who have come before. They are there on the edge, what I see as I stand on the top rung of a stepladder unsure of my balance. They are trying to get my attention, tell me we can talk where the place between the living and dead is as thin as the sheets I use to try to block the sun’s glare. This is when I head south, cross La Veta Pass and make my way toward New Mexico. As soon as I turn onto Hwy. 159, the landscape changes for we are in what once was Mexico. You can feel the difference whatever it says on the map. This is where saints live in every table set out for the dead. Where faces of those who farmed at high elevations dried into ridges like jerky chewed when fresh meat was low. San Isidro is there with plow and two horses, top center. And no matter how many times I arrange the altar in my living room, put out the Chivas Regal Mother loved together with photographs of her both young and old and a small portion of ashes not given up to the sea, it does not feel like the altars in San Luis before you cross into New Mexico. People there practice a communal style of sharing land for grazing, gathering firewood, and hunting based on the original land grant to get through winters harsh at 8,000 feet. On Good Fridays, I climb the trail past the Stations of the Cross cast in bronze to the mesa where a brilliant white shrine stands in the sun. And on the bottom shelf is not an apple from the Tree of Life two rows up, but a pear in the chalice that will offer wine on Easter Sunday. Kyle Laws Kyle Laws is based out of Steel City Art Works in Pueblo, CO where she directs Line/Circle: Women Poets in Performance. Her collections include Ride the Pink Horse (Stubborn Mule Press, 2019), Faces of Fishing Creek (Middle Creek Publishing, 2018), This Town: Poems of Correspondence with Jared Smith (Liquid Light Press, 2017), So Bright to Blind (Five Oaks Press, 2015), and Wildwood (Lummox Press, 2014). With eight nominations for a Pushcart Prize and one for Best of the Net, her poems and essays have appeared in magazines and anthologies in the U.S., U.K., Canada, and Germany. She is the editor and publisher of Casa de Cinco Hermanas Press. ** En Mi Alacena Hay Muchas Cosas. There's a lot of stuff in my cupboard. There are some things of great value but also a lot of worthless tat. Some things I'm embarrassed about and there are one or two skeletons, skilfully hidden behind other stuff, that I'm downright ashamed of. The trouble is, I can't empty this cupboard which isn't really a cupboard, more an étagère where everything is on show and once things are on the shelves, that's where they stay, and the storage space is limitless. I can, however, rearrange the contents and often do, so when on public view only certain things can be seen. All the look-at-me stuff, the eye-catching ornaments and awards are right there at the front for all to see, but it's the things that are hidden that keep me awake. Like the sin – always, there's the sin. You can't get away from it, and you know whose fault that is? That's right, there they are, centre stage. I can't hide them, nor the serpent nor the tree. The serpent started it and the woman succumbed and persuaded the man to do the same. Now I have to share their disgrace and fate. Because of them, sin is like a congenital virus which manifests itself in me no matter how hard I try. So, am I responsible and guilty or am I a victim? It seems that I'm held responsible anyway, but I met a man who said it didn't matter. He told me he would say he committed my sins and take my punishment too. I can't tell you how happy and grateful I felt, but I'm still ashamed of my blackened soul. He told me not to be, to just trust him... ...y todo estará bien. Stephen Poole Stephen Poole served for 31 years in the Metropolitan Police in London, England. He studied Media Practice at Birkbeck College, part of the University of London and also trained at the London School of Journalism. His articles and interviews have appeared in a variety of British county and national magazines. Passionate about poetry since boyhood, his poems have appeared in The Ekphrastic Review, Poetry on the Lake, LPP Magazine and The Strand Book of International Poets 2010. ** Precious Gift I sit on my recently deceased mother’s favorite sofa, the scent of her sweet perfume still lingering in the air. I stare at the cabinet that holds all of her Mexican figurines, her favorite, the girl in mid-walk, wearing a pink dress, holding a red umbrella. My mother was an avid collector. When my parents honeymooned in Mexico, they came upon a small antique store where she fell in love with the girl holding the red umbrella. My father purchased it and every year after, they’d return to Mexico for their wedding anniversary where he’d return to the store and surprise her with more. Some family thought it was a waste of money, but my mother thought it romantic. Sitting here, I wonder what I’ll do with all these since my parents have passed on. I finish my tea and smack my lips together. I’ve decided. I will return them to the antique store for other fortunate couples to buy and create their own history. Love is too precious a gift not to share. Lisa M. Scuderi-Burkimsher Lisa M. Scuderi-Burkimsher has been writing since 2010 and has had many micro-flash fiction stories published. In 2018 her book Shorts for the Short Story Enthusiasts, was published and The Importance of Being Short, in 2019. She currently resides on Long Island, New York with her husband Richard and dogs Lucy and Breanna. ** High Little Cupboard I The voices in the other room dribbled through the doorway and said strange things the boy wouldn’t understand. He was flush with fever, cheeks rosy red and damp beneath the blankets and sheets. It was a sunny day, the light crept through the crevice between the curtains, arching over the ceiling in a bright line that made tiny shadows in the plaster. The brightness almost reached the cupboard on the farthest wall. He closed his heavy eyelids again, went to sleep. II Whenever the boy awakened in the dark hours, there was only the dull luminescence of an oil lamp flickering on the corner table. It cast shadows against the hickory wood doors, which appeared to be shuttered. His dark hair felt wet and sticky across his forehead. He wiped at it with his pajama sleeve, which was train print. This knowledge felt reassuring in the lonely hours, late at night. His eyes were blurry as he shivered and pulled at the layers of hand-sewn quilts, raising the patchwork of all those non-train-print bearing scraps of pajamas from yester-years up over his head. III The morning light was grayish. There was frost on the windowpane. He sat up and drank some warm liquids that had been left nearby for him. There weren’t any voices now, but his sight was clear and he wasn’t cold anymore. He looked over at the cupboard. Its doors were slightly open, and he recognized the red coloring in the opening as the boots of one of his favorite figurines. That made him smile as he fell back into sleep-land again. IV He felt better at last and quietly rose to walk from his bed, while the newly laundered sheets were left trailing upon the floor behind him. He crossed the small space on bare feet that stepped quietly upon the wood flooring. On tip-toe, he triumphantly opened the cupboard doors outward then peered in at his treasures. He laughed a little, like seeing old friends again. He was well now and these dolls would pass the time until school should begin. Tamara J Luckinbill Tamara J Luckinbill is a poetess and writer with many unpublished works. She resides in the Gold Country of Northern California with three furry beasts, two angelic fish, eight enchanted chickens, a cock and a fairy child. Visit her visual tidbits on Instagram @Wings_and_Tales, explore her interests on Twitter @WingsandTales and find her travel writings at DanceUpontheEarth.blogspot.com or read her fantastical blog (where she stretches the truth, but tells it honestly) at WingsandTales.me ** Doll House She arranges and re-arranges figurines in the cupboard of her miniature life. Figurines, tangible symbols that she attaches to abstract realities slipping every moment. She picks up the dolls, washes them with the pain of wispy greying recollections and burnishes them, once a day, with love. She then stacks them in their place, not necessarily in the same order. And conveniently invents new stories to replace ones that have deserted her without so much as a goodbye. ‘What’s the story behind this one, Aviya?’ asks little Radhika, pointing to a pair of oxen bound by yoke. She stares at them with her cataract-beset eyes and tries to fish the right words from the jumbled mess of her memory. Her arthritic knees ache from sitting cross-legged on the mat for five full minutes. She must have toiled and trudged in her youth, just like these oxen, to have been gifted such painful joints during old age. ‘Thatha bought them as a present for me,’ she says. ‘Got it all the way from Mexico.’ Radhika’s mother, her daughter, Alisha rolls her eyes and says, ‘No ma, we bought it during a trip to the funfair when I was three, the time you bought my first roll of pink cotton candy.’ A tinge of exasperation creeps into her voice when she says, ‘Remember?’ ‘Aviya don’t know, aviya don’t know,’ cries Radhika and runs away. It’s excruciating, living life like this – unmoored from the past, dangling in the present, with no desire to see the future and sleepwalking through a senile life. She looks at the other miniature figurines. There’s one of a sheep, the whiteness of its wool preserved through decades. Then there’s one of a man resting on a horse. Her late husband must have brought them Vienna when he was sent onsite from the Company. What was the name of that Company? She racks her brains. And then there’s one of a lime green pear inside a goblet. ‘Ma, come for lunch,’ calls Alisha. ‘Coming,’ she croaks. She leans on her palms, bends on all fours, heaves herself up and ambles to her room. She finds the yellowing Classmate notebook. A purple ballpoint pen rests beside it. She scrawls slowly with her crooked handwriting. Alisha – daughter, Radhika – granddaughter. I love both of them. She hears the clang of cutlery being arranged on the dining table. It must be time for dinner. Preeth Ganapathy Preeth Ganapathy's writings have appeared before in a number of online magazines including The Ekphrastic Review, Visual Verse, Willawaw Journal, Buddhist Poetry Review among others and is forthcoming in Mothers Always Write. She is also the winner of Wilda Morris’s July 2020 Poetry Challenge. Currently she works as Deputy Commissioner of Income Tax in Bangalore, India.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|