|

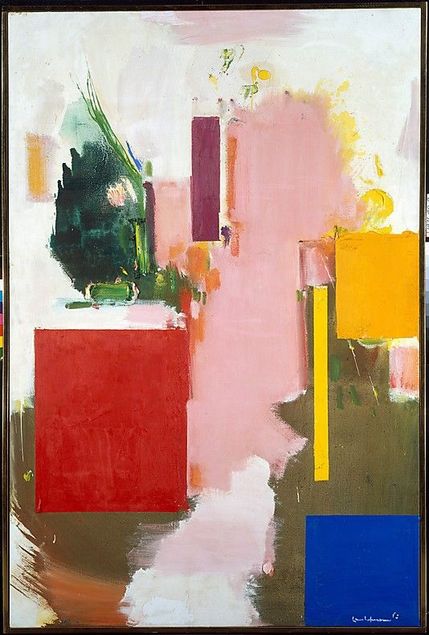

Exhibition “The ability to simplify means to eliminate the unnecessary so that the necessary may speak.” -Hans Hoffman Brushing a wisp of grey hair from her forehead, Mae applies a coil of clay to the nude she is sculpting. With her thumbs, she smoothes and shapes a ridge of tightened muscles across the stomach. Then she steps away from the sculpting stage and stares. Slowly encircling the form, she tries to memorize the various angles. There is still too much, she thinks, that is unnecessary. She chooses a small steel scraper from her tool tray and shaves off more clay from the waist and thighs. Then her practiced fingers, stained red by the terra cotta clay, reshape the hanging breasts. She dips her rounded end brush in water and better defines the cleavage. To create the look of skin, she dabs the surface with a slightly moistened sponge, softening the way the light hits the clay. Two feet tall, the form will be a miniature of herself about to spring into a dive: knees bent, calves tensed, thin arms raised and flattened against the soft curls shoved back from the ears, toes starting to push off into whatever lies ahead. She had first planned a more traditional pose and had finished a sketch and fashioned a maquette of her seventy-five-year-old self draped in silk and seated on a stool, meditatively glancing over her shoulder as if for a great and famous artist. But once she finished these preliminaries, everything felt wrong. She didn’t like to sit. She didn’t own any silk. If nowhere else—she thought—she deserved the action of her imagination. Besides, action meant change, and no matter whether she planned for it or not, change seemed to splash all about her. Better to bend her knees and prepare to spring forward. Of course, there was always the matter of losing balance while she waited. That was the risk. It had happened before. Even last week, waiting on her front porch for a ride, she had lost her footing and nearly toppled over the handrail into a pile of leaves she had raked earlier that morning. Had she instinctively prepared for her own fall by softening the ground with such bright colours? Now, with wood ribs in hand, she scolds herself for being silly. In truth, she had been too exhausted to bag the leaves. And she had grabbed the handrail hard and righted herself successfully. There was nothing else to it. No need to tell anyone. She hadn’t said a word when her ride pulled up. With the wood ribs, she trims more clay from the muscled calves, then looks again at the slightly off-balance form of herself. What was the best way to give the illusion of motion? To suggest movement without sending the statue toppling to the floor? She scores the base and shores up the foundation with additional clay. With a metal scraper, she arches the toes a centimetre more. Was that it? She takes a wire brush and textures the clay into long blades of grass curling in the wind over the statue’s heels and toes. Again, she stands back, then reapplies the pressure of her tools. She scrapes away additional clay to better define the blades. More and more, they resemble waves. She rolls another coil. She attaches the coil with slurry then transforms it into a twirl of seaweed climbing one ankle. “Maybe,” she thinks, and steps back again to look. Her upcoming exhibit—a retrospective—is two weeks away. “Self, Diving” will be the final piece. What she wants it to express, she is still discovering. She keeps the seaweed in place and looks again at the angle of the head. This is the last form friends and patrons will consider as they return to the ordinary world: a head slightly tucked but moving forward, a body following that determination. Her opening sculpture is also a nude, herself at seventeen. In that one, she is kneeling, her head lowered in prayer, her palms raised in praise. If patrons were to look closely, as they should, they would see the statue has no eyes, merely large sockets where Mae has forced her thumbs to dig in. From experience, Mae knows most people will focus instead on the hands. With a metal teasing needle, she has carefully crafted each clay fingernail to point toward heaven. Much of Mae’s other work is in oils, impressionistic paintings of her travels in France or the farmlands of southern Ohio where she played as a child. Points of orange and red merge sun and fields. Lavenders and blues blend to offer up a familiar landscape of hills. But there are unexpected pieces, too. Sharp angles and incongruities: it is a different type of sculpting. With colour and shadow, she can shape perception. She can adjust expectations. She can give the illusion of movement where there is none. She can soothe or surprise. Sometimes, Mae starts off trying to do the one, but ends up accomplishing the other. How long had she stood back and stared at “Prayer”? At one point, she had thought she was done, then surprised herself and rebuilt the lowered face, adhered more wet clay, and plunged her thumbs in. The oils, also wonderfully messy, exposed the hidden. Even in the idyllic landscapes, something else lurked—a crow in the corner of the sky, the tip of a scorpion’s tail descending in sand. Yet in scenes she deliberately cast as unsettling (as in a series one reviewer dubbed “Angelic Nightmares”), something good crept in. The combination of color and line surprised and soothed. Fear transformed into worship. How this was possible, she could only articulate with brush or chisel. Words were relegated to short titles—unpolished doorknobs to push open the meaning. The eye should do the rest. Even so, it could be troubling to title the character studies. Those of strangers were simple enough, but the paintings or sculptures of those she loved? How to suggest duality? To recreate the real but not harm the original? She thought of the details that made up love—the lifting of a tea cup, the sound of your name in someone else’s mouth, the glance sculpting years of recognition—not one seemed small enough for words. But art—that could begin to hold a life, all the dark curves and jagged edges. Mae ponders again her upcoming show. She thinks of those she’s loved these last decades. She does not know how the people she calls her family will react. She is most concerned about Lauren. After Mae retired from teaching, she moved to the other side of this small Ohio town to that one-story brick home where her best friend, Eva, had lived. After Eva died at 60, her daughter, Lauren, offered Mae first choice of renting the house—not even renting, really, just occupying and paying the utilities. It was just two houses from where Lauren and her accountant husband were starting their family. How could Mae say no? She had known Lauren since she was a shy, introspective twelve-year-old intrigued by music. When Lauren and her mother had moved to town, the two had performed family duets on the organ at Mae’s church. It was there the young girl came alive, her thin legs stretching to push the pedals, her eyes lost in the vibration of notes. It was the love of the arts, of worship, and of children that brought Mae and Eva together. Both were women without a husband (Mae never had one; Eva’s died in war when Lauren was young) in a church where men were the deacons and ushers. In her mind, when she thought of these men at all, they were standing stiffly at doors and under archways, pointing this way or that. Their suits were the dull grey of granite. They used words like road signs or exhibit titles—short and practical. Their presence was helpful but not substantial. But the arts—music, painting, even Sunday school crafts and sanctuary “decorations”—these were the sole domain of the women, and Mae and Eva took them on together. They organized church luncheons complete with tea sandwiches, organ recitals, “tasteful” flower arrangements, and invitations with precise calligraphy. After two months of a class they called “Painting by Verses,” they led the Sunday school teens in transforming one wall of the Fellowship Hall into a depiction of The Last Supper. The younger children made stained-glass windows out of coloured cellophane and earlier—for Palm Sunday—choreographed their own dance of palms, complete with pirouettes and grand jetés. Mae remembers the pre-teen Lauren helping with both: a brush in hand, adjusting the tint of Judas’ hair, and with second-grader Jenny Mather, holding her hand as she attempted arabesque. Most often, though, Mae thinks how she and Eva read Bible passages aloud to each other, then tried to convey their essence through notes or form. Their experiences of awe similar, their expressions of such nonetheless remained different though complementary. Where Mae questioned, Eva encouraged. Where Eva doubted, Mae clarified. “In the beginning was the Word. . . .” Eva had recited one Sunday afternoon in her kitchen, then stepped quickly to the parlor to bring alive the beginning of Copland’s “Appalachian Spring.” Mae, on the other hand, had immediately envisioned bold charcoal lines streaked across a canvas as large as a refrigerator. All she had wanted to do was bow down. She had opened her sketchpad and begun the first confident strokes of what later became an abstract rendition of Creation. Near the end, she had positioned her own form in the lower left-hand corner: small, prostrate, alone. Even so, she had felt less alone with Eva than with anyone else. That they could share the intimacy of prayer—of both doubt and belief—in a small way made up for the expected institution of marriage that Mae had wanted but somehow missed. It was companionship, not romance, that she felt had eluded her. It was the symmetry of family. Having no children of her own, such proximity to family was at times enough for Mae. Sundays after church, while Mae and Eva sat lazily in Eva’s kitchen, sipping tea and talking, Lauren was always nearby drawing pictures or practicing her scales. Her slight movements were the backdrop to their conversations. The shape of her shadow added to their light. Often, of course, the proportions had shifted. Groupings had naturally realigned themselves. Some Sundays, Mae would paint the mother and daughter playing at Eva’s organ together or leaning against the magnolia tree in their backyard, sharing a memory. At these times, it was enough to be the one recording the relationship—the artist observing. It gave her time to step away, to see the forms anew and how they adjusted to each other in different light. And, of course, there were the times when Mae was absent altogether, when she was not even there to observe but across town at her own apartment, in a life she sometimes forgot was separate from this other duo. Still, she had created with them more than a decade of such mother/daughter portraits—from twelve-year-old Lauren in braces to the new bride handing her bouquet to a kerchiefed and frail Eva determined to play at her daughter’s wedding. In those last months of struggle, Lauren had performed at church alone. Sometimes, though, with her daughter’s help, the old Eva had resurfaced, had leaned into her own organ, sounding her notes vehemently, passionately, running over the more polished, careful playing of her daughter. Those days, both Mae and Lauren had applauded. When, in her will, Eva had left the organ to Mae but the room to Lauren, both were surprised. They knew one couldn’t be separated from the other. Eva’s music belonged to both of them, but only within the context of the home she had created. When the lawyer added that Eva had left the study to Mae but the deed to Lauren, their surprise transformed into a slow, soothing understanding. For a week, both dwelt in their own quiet grieving. Then, as if Lauren were simply arranging to again pick Mae up for church, the younger woman offered up her mother’s home. It was a type of sharing she had grown used to. Lauren’s entire family helped Mae move the following month. The girls carried her paints and clay. Daniel helped Lauren with the paintings, pottery, and statues. The moving men he hired did the rest. When the transition was over, the first thing Mae did was hang the mother/daughter portraits facing the organ. Without a word, both women understood each other’s gratitude. Now, a decade after Eva’s death, the house sustained, developed, and redefined these connections: the kitchen where Mae and Lauren drank tea together, the parlor where Sunday afternoons Lauren and her girls huddled close at the organ, Eva’s decent-sized study that got the morning light and became Mae’s studio, and the two-minute walk to a family Mae could claim. Mae was Me-Ma to Lauren and Daniel’s girls: Elizabeth Eve, 11, and Mae Lynn, 9. Last summer, she had again sketched their portraits in the small backyard: Lizzie, her arms crossed in defiance near the rosebushes; Mae Lynn, dreamy-eyed and upside down, dangling by her knees from the magnolia tree. Of course, they had made her promise these portraits would also be in the upcoming show. It was not a promise Mae had thought she could make. Instead, she had nodded that they—each sister separately or together—would certainly be present. And so she started another portrait of the girls, but for this one there was no sitting—at least not one of which they were aware. She began in secret, moving the organ bench to her studio and covering it whenever Lauren knocked at the back door. The mahogany became a magnolia branch with Mae Lynn’s dangling knees. On the young girl’s nail-polished toes, Eva’s eyes winked. Everywhere magnolia blossoms opened in welcome. When she was finished, Mae propped the bench up vertically near the keyboard. She brought in more portraits of Eva and Lauren, of Lauren and her girls, of Lauren and Daniel, and of the girls together and individually. Once she talked the newspaper boy into helping her; three times the mailwoman. She covered the parlor walls with the family’s faces and bodies. Then she stood back and observed the crowded room. Twice she lost her balance, but started again. She moved “Prayer” to the forefront, just inside the front door. Its hands lifted toward the instrument. Those days when a concerned Lauren called, Mae feigned a cold. When Lizzie and Mae Lynn wandered over, she blamed exhaustion. When her “inherited” nieces begged to come in, the older woman admitted she was working hard on the “secret” exhibit and that she wanted to wait until she was finished before showing even them. She would visit them soon in their home, she promised. When she did, they ran to her with Super Good! scrawled across the top margins of math tests. Lauren made Mae’s favorite meal— Blanquette de Veau—while Daniel explained, again, how to report income on any artwork she would sell. Then Mae announced that she had spoken to the director of the Community Center and that the exhibit could now be at her home. She would, she explained, note the change of location on her calligraphy invitations. Just afterwards, when she glanced at Lauren, Mae couldn’t interpret the canvas of her face. Too quickly, her friend’s daughter stood to clear the dishes. Once at the sink, her back turned, Lauren added, “Of course, we’ll all help.” A second later, Daniel smiled his half-smile, gathered the dirty silverware, then asked, “Mae, how about some dessert to fatten up those bones of yours?” The girls, anticipating a place in the exhibit, jumped up and down, then danced around the room, striking poses and chanting “Me-Ma, Me-Ma.” That night, Mae had begun work on the lower-left leg of Eva’s organ. Now, weeks later, Mae stands back from her work on “Self, Diving” and walks into the parlor to study the transformed instrument. Intricately painted seaweed spirals around the dark wood of each leg and up toward the keys. On the back panel, she has outlined Lizzie’s foot tapping the rhythm from her iPod. Eva’s praying face hovers in the background. On one side panel, Lauren—standing tiptoe on the top of a cross—reaches for a half note that dangles from one of her mother’s raised hands. On the opposite panel, Mae has painted in oils her charcoaled rendition of Creation. On the organ’s front piece, she has shaped the dead and smiling Eva, huddled together with her daughter and granddaughters beside the magnolia. In the background—and much smaller—Mae has drawn a pregnant replica of herself bringing to life the promised family portrait. Even now, Mae imagines Eva’s impromptu performance of “Appalachian Spring.” The elderly artist stands back and stares. What is the best way to give the illusion of music? To suggest the notes of someone’s life? After all this, she is still not sure. She walks back to her studio, then turns again to the unfinished statue. She pinches the fluid blades into more definite waves. She adds note-shaped leaves to the climbing seaweed. Again using her metal teasing needle, she heightens the illusion of tightened calf muscles atop the layered water. What is beyond the statue refuses to be known. Under water, sound waves bend differently. Once she accepts such changes, she will let the clay harden to the leather stage. Then she will need to cut open the figure and hollow it out. Otherwise, it will explode during firing. As she learned long ago, only at 1100 degrees will the necessary transformation take place. She knows just where she’ll position the finished statue: on the top edge of Eva’s organ and closest to the side door where her frequent guests will exit. She may need to change the work’s title. She may need, at seventy-five, to learn how to swim. It should not be that difficult to teach herself. Marjorie Maddox This story was previously published in The Art Times and in What She Was Saying (Fomite, 2017). The accompanying artwork by Hans Hoffman was an editorial selection, not the inspiration for the story. Sage Graduate Fellow of Cornell University (MFA) and Professor of English and Creative Writing at Lock Haven University, Marjorie Maddox has published eleven collections of poetry-including True, False, None of the Above (Poiema Poetry Series and Illumination Book Award medalist); Local News from Someplace Else; Wives' Tales; Transplant, Transport, Transubstantiation (Yellowglen Prize); and Perpendicular As I (Sandstone Book Award)-the short story collection What She Was Saying (Fomite Press), and over 500 stories, essays, and poems in journals and anthologies. Co-editor of Common Wealth: Contemporary Poets on Pennsylvania (Penn State Press), she also has published four children's books: A Crossing of Zebras: Animal Packs in Poetry, Rules of the Game: Baseball Poems ; A Man Named Branch: The True Story of Baseball's Great Experiment (middle grade biography); and Inside Out: Poems on Writing and Reading Poems + Insider Exercises. For more information, please see www.marjoriemaddox.com

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|