|

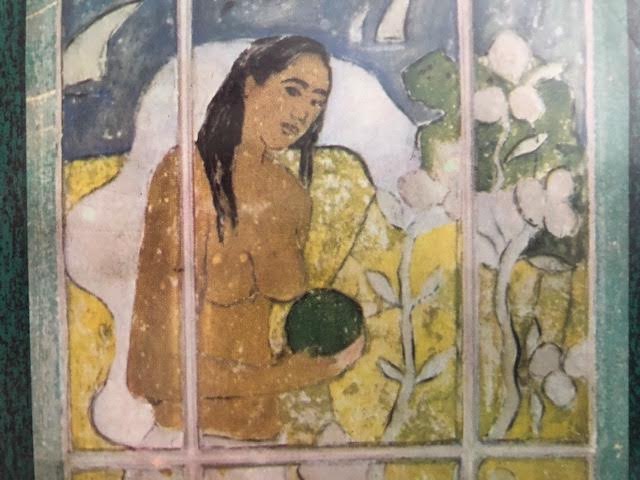

Fall On Your Knees We met at the public library across a scratched wooden table. He asked “What are you reading?” At thirteen, I was thrilled to be noticed, particularly by a boy who looked old enough to be in college. When I told him Gentlemen’s Agreement he said: “I loved that book.” He held up his own volume, which was called, innocently enough, The Two Worlds of Somerset Maugham. We discussed Maugham briefly, discovering that – not surprisingly – we were equally bookish. I had finished Of Human Bondage months before. “I liked the part about the Oriental rug,” I said that first time we spoke. The boy nodded. I realized (not then, later) he had no idea what I was talking about. I remembered that encounter – from 30 years ago -- when I read the indictment this morning. “She’s yours,” Mo said handing it to me. “Cassie Crane. A misdemeanor but sexy.” He meant “sexy” the way we use that term in the prosecutor’s office, signifying a good meaty case. That’s all we mean by it. I read on, wondering if I should say I didn’t want this one. Mo could give it to Rudy, with his beefy tattooed arms, who’s next in line. But I say nothing. “What are the two worlds of Mr. Maugham?” I asked that first day in the library, across the table from the boy in the reading room. The boy blushed deep red. “Britain and Tahiti.” He looked down. “And Samoa.” “That’s three worlds,” I said, trying to be clever. I was smart, but a fool. Either the librarian or someone else told us to shush, which ended the conversation. When I returned to the library three days later, I was relieved the boy wasn’t there. “It’s surprisingly popular,” the librarian said crisply, handing me the book after a short wait. I sat at the table, hoping to learn what secrets were in the book, what made the boy blush. It was the back cover, surely: a Gauguin painting that, the blurb explained, Maugham found and rescued from destruction in 1917. A golden-skinned bare-breasted girl, with pale puckered nipples, held a large green fruit. The painting was called Tahitian Eve in the Garden of Eden and the girl was Tahura, Gauguin’s “child mistress.” Three weeks after our first meeting, the boy and I were alone on the second floor, in the stacks. It was the fifth time I’d seen him at the library since we met. Always before, there’d been others around, always – until now – we were in the reading room. This was different, but not completely unexpected. “On your knees,” the boy commanded. I looked into his gray eyes, which I’d noticed the first time we spoke: the grayest eyes I’ve ever seen (even now, 30 years later), with thick dark lashes. “On your knees,” he said again, more softly than before. I was half-hoping he was kidding, half-not. In the three weeks since I met him I’d turned fourteen. He was three years older. I still remember the smell, of wet paper and metal; the day outside, which was rainy, the streets black and slick, the trees shrouded in moisture; and the floor I knelt on, which was not carpeted, but harsh, unyielding concrete. Most of all I remember his book and the painting on the book jacket that brought me to that moment – a moment that would be repeated throughout my adolescence, not just with him. After meeting with Mo, I go back to my office. The police report in United States v. Crane reads something like this: Crane entered the East Building, National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. She walked into Room 7 and stood before an oil painting by Paul Gauguin entitled “Two Tahitian Women” valued at an estimated 80 million dollars. Crane struck the painting with her right fist. Eighty million dollars. Imagine. Fact (discovered in the library when examining the boy’s book): Tahura not only looked my age, but looked rather like me, with scraggly black hair hanging past her shoulders, a soft chin, overlarge lower lip, and ears that were too small. Fact: Tahura was thirteen, same as me – although I would turn fourteen the next week. The author of The Two Worlds of Somerset Maugham shared details about her. Gauguin “found” Tahura while riding horseback near Taravao. Her mother made her go with him and she ran away. He came for her again. When she misbehaved, he spanked her. When she fidgeted while he painted her, he slapped her. Gauguin described her as “a large child, slender, strong, of wonderful proportions...she gave herself to me ever more loving and docile . . .”. I hated that book, even then. Hated the author, hated Maugham and Gauguin, hated the grey-eyed boy for reading it, and for showing it to me. Hated the librarian for finding it on the shelf. Hated myself for how it made me feel, desire unfolding within me, an exotic, swollen bloom. Thirty years later, I am bound to uphold the Constitution, to pursue and bring offenders to justice. I read on in the indictment: “Subsequently, Crane was read her Miranda warning. Asked why she had tried to take the painting off the wall, Crane stated: ‘Gauguin is evil. He has nudity. He is bad for children.’ Crane vents her homophobia. She is obsessed with the two women in Gauguin’s painting. The Washington Post references her in “A Short History of Crazy Art Attacks.” But I have to wonder just how crazy she was. The painting she attacked wasn’t my portrait of Tahura. It was that picture that changed my life, not the same painting that roused Cassie Crane to fury. But still I understand her. I wanted to slash a Gauguin once, too. Nancy Ludmerer This story first appeared in Fiction Southeast, where it was a finalist in their 2016 Hell's Belles contest. Author's note: "The Gauguin painting that inspired the flash fiction was discovered on the glass door of a house in Tahiti and reproduced on the book jacket (back cover) of the first edition (1965) of Wilmon Menard's biography of Somerset Maugham, The Two Worlds of Somerset Maugham. The door painting itself was discovered in 1917; the actual date it was painted seems to be unknown. (Photographed by Leonard Ross, Courtesy of Mr. and Mrs. Philip Berma, Allentown, Pa.)" Nancy Ludmerer's fiction and flash fiction appear in Kenyon Review, New Orleans Review, Electric Literature, Mid-American Review, Grain, and Best Small Fictions 2016 (a River Styx prizewinner). In 2020, her stories won prizes from Carve, Masters Review, Pulp Literature, and Streetlight. She lives in NYC with her husband Malcolm and their recently-adopted 13-year-old cat, Joseph. Twitter: @nludmerer

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|