|

Flying Vinnie

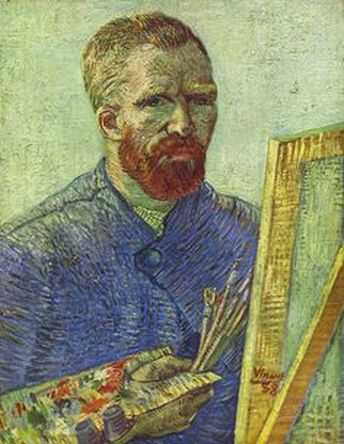

He’s refused a drink from flight attendants, not because the absence of absinthe or, hollow as pipes, he is made from the lint of rust. His iron was formed to stand in gardens with others of his sort who tip their hats to rain and hail from the straws poking out from the undignified maws of paper drink cups filled with slushy hues never seen in nature, though likely viewed through the fae eyes of life on an easel. Simply, he is more taken with the field of clouds ungluing next to his windowed seat, and complains about my decisions: Lack of canvas will cost him his visions. Lack of canvas will cost him his visions, though his arm is forever raised with brush at the ready, poised to jab as if to box, and he whines to anyone who listens – a toddler kicking his seat from behind, the elderly woman on the way down the aisle who calls me Dorothy, businessman, soldier, selfie-taking student with her finger in the metallic wound of his mutilated ear. “Wet Willie/Dry Vinnie,” she captions on social media, going viral as soon as we land. No “thank you” for purchasing him a seat instead of sending him wrapped in a crate. Instead of sending him wrapped in a crate in the frozen digestion of the plane like a dog or stowaway immigrant, bundled in plastic so bubble-bright it’s more luminescence than protection, I piggy-backed him as in my youth I did my own son, surprised by such depth for someone so incomplete. “Woman,” Vinnie said from behind my ear, “You hold me too close to the bristles. Ease up the grip. Try for a sensitive, painterly tip.” I didn’t tell him only one painting sold before his suicide, that his weight is now of a coffin, his mien of a terrorist. Now a coffin, his mien a terrorist – he hurts us not at all at security. Though a sculpture, he’s still a celebrity, an apparent, un-humbled anachronist. It was the easel that caused the problem. Welded to his right foot, rising upright, it didn’t fit with him in the flight’s limited, overhead compartment. In the end, I was forced to amputate his vocation, mark it with my address and send it to wait with the confused mess of last on and first off: strollers, car seats and walkers. Then I bought him an extra ticket in the exit row for the room, tried not to think about bank account gloom. Trying not to think about bank account gloom, I ask Vinnie, “Why all the sunflowers?” He snorts. “I’ve heard people say they were painted by me for Paul Gauguin’s room. That pisvlek! He was the worst houseguest. I regret inviting him to Arles. He didn’t even come to the hospital.” This wasn’t the incident with his chest when he put a bullet into it instead of painting landscapes of the Auver fields but the one with a razor where he yielded a lobe rather than whiskers from his head. He says something about “la tristesse.” He says, “I wish I could pass away like this.” He says, “I wish I could pass away like this.” “You did,” I tell him. “You died in the arms of your brother, leaking your scarlet charms. Fading to yellow, you were dismissed.” He says, “Speak to me not like a poet for the good of all; no one reveres such garbled intent. Express yourself as much as you can your kernels of content.” Will a snack soothe him? Probably not. Nervous as he is, were he born this era, he’d be lactose intolerant, gluten-free, deathly allergic to all kinds of nuts. Not responsible for his temperament, still, I am sorry for this circling current. I am sorry for this circling current, but growing so tired of his sadness, his melancholy for Yellow House, lectures on Japanese woodblock prints, his memories of the brothel woman to whom he gifted his ear – what a choice that proved to be, his act spreading like a rash over a town crying for his commitment. Perhaps I should have overlooked his bulk at the gallery among the daintier, bent-steel figures of Toussaint and Renoir. Now against the glares of others, I block Vinnie’s access with Jet Blue blankets and request a drink from the flight attendants. Jen Karetnick Jen Karetnick is the author of three full-length books of poetry, including American Sentencing (Winter Goose Publishing, 2016) and The Treasures That Prevail (Whitepoint Press, 2016), as well as four poetry chapbooks. She is the winner of the 2015 Anna Davidson Rosenberg Prize. Her work has been published widely in journals including Barrow Street, Cimarron Review, december, North American Review, Poet's Market 2013, Seneca Review, SLAB, Spillway, Spoon River Poetry Review and Valparaiso Poetry Review. She works as the Creative Writing Director for Miami Arts Charter School and as a freelance dining critic, lifestyle journalist and cookbook author. Her work can be found at https://kavetcnik.contently.com.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|