|

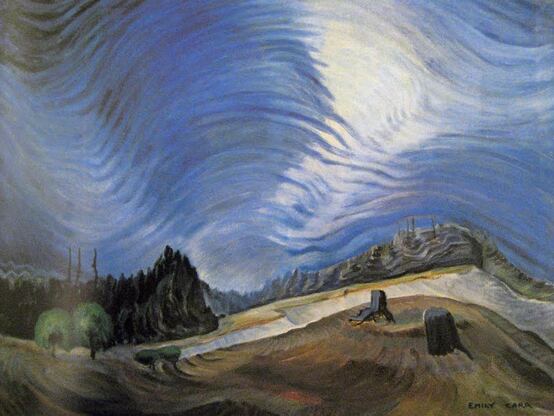

Force Fields (Emily Carr, Canadian artist & writer, 1878-1945) Stand still. The forest knows where you are. You must let it find you. David Wagoner i. Sky The subject is movement —and sky: a rising surge of repetitions, brush strokes like auras, arcs rushing up through the undergrowth, across the gravel pit past loggers’ culls beyond the vertical spars of trees. Today, Vancouver’s children pay crayon rainbow homage. To be an Emily, all you need are bright, vibrating lines, your vision drawn, as hers was, onto fields of air. Then file out of doors, art in hand, and down the sunny walk. Never mind her vanishing hills, ridge upon ridge green brown to green black to green blue-- or the reverse avalanche of clouds outdistancing the upthrust trunks, the roots’ rock-splitting grip. ii. Monkey Puzzle Tree (Stanley Park, Vancouver, B.C., 2002) Serrated, drooping, with stiff overlapping leaves, each branch makes a ristra of knife- edged, succulent stars. A cactus in the rain forest? One of her cubistic dreams? Its palette spells restriction, a dark, puritanical green, but the underwater sea creature it conjures casts about in wild contortion. Snaking branches, Medusa’s tortured hair. Independent. Don’t touch! No other of its kind on the continent. A loneliness, beloved, she might have said, of the sky. iii. Totem (Tsatsinukwomi Village, 1907) I slept in tents, in roadmakers’ tool sheds, and in Indian houses. I travelled in anything that floated on water or crawled over land. Emily Carr No more the timid student, too shy to view a naked model, you have come up the coast by boat, alone, and are not afraid now to sleep alone in the emptied longhouse. You step gingerly past banana slugs, dodge famished cats that swirl underfoot as you tramp the rotting plank walk out to the edge of the abandoned Indian village. There, through clouds of mosquitoes and stinging nettles higher than your head, you slip, fall before D’Sonoqua, woman of the woods, stare stunned into the wild OO’s of her eyes, the black cavity of her mouth, its breath filling the air between the outstretched arms, the dangling, eagle-headed wooden breasts. Easy sacrifice—if burning skin is all it takes to find her, this towering totem, partner of Raven, figure to warn children against. Witch Woman, hungry, unappeasable, you must capture her before moss and rain reclaim the heavily sculptured torso and the eyes that echo through you until you hear your own fear beating inside her body’s hollow drum. iv. Bole or is it burl? The knot on the trunk, the condensed whorled pattern in the wood. Then the unraveling, the out- reaching. Knot as navel, wrist, magic spot these ribbons extend from. The witch in the wood is breathing, extruding a bouquet of scrawny spruce fingers, a root system grasping for air twenty feet above the ground. v. Sea So this is how forest becomes sea-- a voyage the mind takes, anticipating boundless waves, new islands of light, the brush stirring in its wake the fingers tagging clumsily along. vi. Weather Emily, old girl, you have us bouncing through a whirl- pool you long ago defined. With what relish you frame these tumults of cloud, boiling eddies of sky, thunder we can almost see crumpling the canvas surface. vii. Flesh Tempting to ask why you would have none of it, not Georgia’s flagrant petals or Frida’s florid hearts. Why you favored greens, not reds. Not flesh but the mind home- bound Emily knew was “wider than the sky.” In love with trunks, ferns, bark, and air, high and fathomless-- abrupt maiden, vagabond sister how can we know you except for these coils, spurts, cascades of writhing growth, a raw sexual force your forests understand. viii. Indian Basket Between its earth-red stripes a tawny grass wind blows like currents around a globe in arrows of circulating light. She wants to breathe inside its brittle flexibility, immerse her face in its darkness, leave it out in the rain and inhale the sweetgrass smell. Recalling Sophie, her basket- maker friend, Emily strokes the knobs grass makes crossing over grass, thinks she might dissolve at the edges, the way its curved sides alter the space around it. ix. Potlatch (Victoria, B.C., 2002) Teatime and the Bengal tiger in the Kipling Room at the Empress Hotel still sends its stuffed snarl through sun- slatted afternoons, potted palms and lace. Down the street, past the place of your birth, herons fly from the park where you painted, soar above your “House of All Sorts” in their daily departure for the shore. Today, D’Sonoqua stands display at the Royal Museum. Klee Wyck the Haida name you, “Laughing One.” But by the time you finish your “Potlatch Welcome” the Crown will already have banned the dancers, locked up elders, grandmothers-- the gift of feasting forbidden, the art of gifting abandoned—and all the weave unraveled until Sophie’s twenty babies arrive half-starved and so silent the grave- stone carver, not unkindly, calls her his best customer, helps keep her tab alive so she might place another marker in the village’s overgrown burying ground. x. House/Caravan (1913-1933) Scrub, rearrange, reorder and resign yourself to reduced circumstance. The King’s radio message New Year’s Eve still makes you cry. Crabby tenants. Fix the plumbing, and the heat. In the center of the ceiling paint eagles, still there. Tlingit design. At last, pack your van. Collect your menagerie. How many dogs? Add boxes, sketchpads, your monkey and the rat. Tighten canvas sides. Put the entire household on wheels. Now leave. You’re off! Summer’s woods at last. You’re old enough to bathe naked in the stream. xi. Horizon Rivers of air fill your later canvases. Above the Strait of Juan de Fuca, headlands you climbed to sketch from, your skies unleash reverberating lines. What did you see but magnetism, subatomic timbres, currents you struggled to make visible until the ethereal became too bright to bear and you re-entered shadow and wood. Green drape of cedar. A trunk’s undulating stalk. Regardless of horizon, all is swirling, fierce, boring not down into darkness but through into light. Here: these pulsing trees frame a birth canal into the deeply scarred, deeply scarved dark-- your hand drawing the shawl of the forest, coaxing her to lift her hem and let us in. Terry Bohnhorst Blackhawk NB: Italicized phrases in the poems are taken from Carr's writings. These sequences are from the author's book, Escape Artist (BkMk Press, 2003). Terry Bohnhorst Blackhawk is the founding director (1995-2015) of Detroit's InsideOut Literary Arts Project (www.insideoutdetroit.org) and the author of five full-length volumes of poetry and four chapbooks. Escape Artist (BkMk Press) won the 2003 John Ciardi Poetry Prize, and One Less River (Mayapple Press) was listed as a Top 2019 Indie Poetry Title by Kirkus Reviews. During her years as an educator, Blackhawk enjoyed using ekphrasis with high school and university students through the Detroit Institute of Arts. She writes about ekphrasis here. Teachers & Writers Magazine / Ekphrastic Poetry: Entering and Giving Voice to Works of Art

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|