|

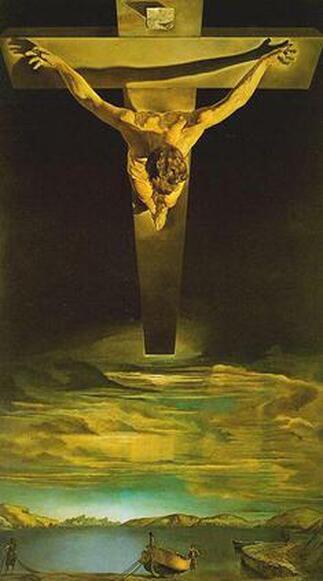

Forever Dali In 1960, my mother and I emigrated from Scotland to Canada to join my father. Our family had faced challenges as a result of my father’s shell shock. In 1957, he experienced a serious breakdown. After a year in psychiatric care, he moved to Canada to start a new life. Two years later, we were to join him, flying from Prestwick, near Glasgow, to Windsor, Ontario. Mother decided we’d travel to Glasgow a day early to visit Dali’s Christ of Saint John of the Cross. Bought in 1952 by the then Director of Glasgow Museums, Tom Honeyman, whom my mother knew personally, the painting was housed in the Kelvingrove Museum and she wanted to see it. “We may never get to come back,” she said. I was only twelve, with no idea why Mother “had” to see this painting. After all, we’d looked at paintings in museums before. Wasn’t this just another painting? We took the train and spent money on an extra night in a hotel, money we could ill afford. Our possessions had been shipped and all we had was a small suitcase each and enough sandwiches to meet our needs until we got on the plane. Next morning, we waited for the museum to open. Once inside, we headed for the Dali, then hanging in a large room, centered on a long wall. Reproductions of the painting are misleading. It’s not as big as one might anticipate—about six and a half by four feet—but it’s huge. We stood in front of it all day and stared. It didn’t matter how much our legs ached or how hungry we were, we couldn’t tear ourselves away. At closing time, Mr. Honeyman came and took Mother and me to dinner, our sandwiches now forgotten, squished and soggy in Mother’s handbag. At dinner, Mr. Honeyman and Mother talked about how Dali had hung a stuntman to see how a human body responded to the gravity of its own weight. They talked about the water below, the bay of Port Lligat where Dali lived at the time, and the Spanish courtiers and their boats so tiny below the hung Christ. Why Spanish courtiers? They talked about the painting’s controversy—a “stunt,” “kitsch.” They talked about Mr. Honeyman’s bargain. He’d paid only £8,200. All this talk flowed over and through me as I ate my dinner, made even more delicious by not having eaten since breakfast, but I don’t remember what was on my plate. I knew that I would never view paintings the same way again, even bad or uninspiring ones, because Dali’s painting was viscerally within me. What it is that mesmerizes? The easy answer is the enormity of our situation coupled with the impact of the painting. But would that have happened with a different painting? No. It was this one. Dali. His vision. For my mother, her words came true. She never saw the painting again, but if I travel to Glasgow, I must go to the Dali again. Every time, it hangs in a different place in the museum, but even when it’s at the dark end of a corridor, it hits me the same way—physically, in my chest, and emotionally, as I fight off tears. The pain of crucifixion jumps off the canvas, a testament to our human capacity for cruelty. Yet, Christ’s drooping head and the absence of his face somehow correlate with the sacrifice the subject represents. It’s inescapable, irresistible, a permanent collection in my being. Aline Soules Aline Soules' work has appeared in Kenyon Review, Houston Literary Review, Poetry Midwest, and The Galway Review. Her books include Meditation on Woman and Evening Sun: A Widow’s Journey. Find her online at http://alinesoules.com, @aline_elisabeth, and https://www.linkedin.com/in/alinesoules/

1 Comment

4/9/2019 09:30:52 am

This was just beautiful--I loved the way you entwine your own life and reactions with this piece of art and it's own origin story...thank you.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|