|

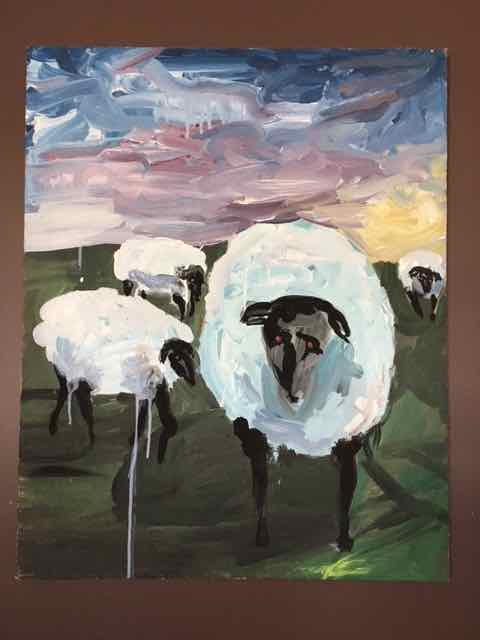

Imperfect Sheep in a Meadow The moment of discovery elicits in me a mixture of affection, nostalgia for a farm I never knew, traveling through Wales, and instant appreciation of a piece of discarded art that might be considered a “second” if art were sold in outlet malls. The idyllic, whimsical scene depicts four cloud-shaped sheep grazing in a meadow. The sheep are not the cotton-white of your imagination, but streaked with a gray hint of sadness. They appear contented though, with a fullness in the belly, yet they are neither adorable nor stoic; their black button-eyes follow you, absent of light. It’s nearly spring and their thick wool coats need shearing, but they don’t look like the receptive type. I remember petting a sheep for the first time at five through a petting zoo fence, startled by how not-soft it was. After years of picture-book conditioning that promised sheep were fluffy pillows, I was disappointed. But I knew it wasn’t the sheep’s fault—that it would have been soft for me, if it had any say in the matter. A trick of the spinning wheel, it seemed to say. The central sheep in the foreground simply stares at the viewer while the other three mill around in the background. I imagine their conversation roams from the mundane topic of clover to more philosophical concerns: Should we resist being herded? The oil painting is on a stretched canvas, unframed, and raw. It’s the size of a mirror over a bathroom sink, and I imagine a sheep looking into it, thinking, Funny how when I chew the grass, that sheep chews the grass, but ultimately reasoning that every sheep is chewing the grass and that it must really get back to chewing the grass. The piece has earned a prominent place in my bedroom: not over the bed but on the opposite wall where I can see it more readily and can meditate on the stillness of the meadow. The farm in my mind’s eye has always been a combination of the Waltons’, bed and breakfasts in the Welsh countryside, and the farm of a friend who had horses and barn cats. I was at home on a dairy farm, in my imagination anyway—no milkings at dawn or haying in mid-summer; just the romanticized version of fresh eggs plucked from the coop and the rambling, white farmhouse, curtains billowing in the breeze. To the eye, the work consists of no more than six colours: white, yellow, green, blue, purple, and black. The tones are earthy and muted, the sheep almost blending into the clouds, the grass swallowing their black feet. The sky is not the picturesque blue shade of a tranquil day, but it’s not menacing either; the possibility of a small purple storm lingers in the distance. Focused on the field, I’m nostalgic for a solo trip to Wales a dozen years ago, exploring all the out-of-the-way villages I’d seen in books. Travel is best done alone, I think, and this trip was a gift to myself after finishing graduate school. It was on a drive through North Wales that I crested a hillside and came upon a flock of sheep grazing the patchwork quilted countryside. I stopped the car and got out, feeling an instant kinship to these animals and their way of life: wandering, resting, and snacking. I watched them in silence as they watched me. We are all so curious about each other, I thought—sheep too. Here was a flock roaming freer than in the petting zoo but still contained by the farm’s boundaries. Even the sheep of my painting were confined by the edge of the canvas. Were there no sheep left that were truly free? The child in me that day still wanted to pet one, but the adult in me was wary of getting nipped. The signature element, however, is, to anyone else, the painting’s flaw. From the body of the innocent sheep on the left, the one absent-mindedly munching on sweetgrass, drips a white streak of paint that trickles, unintentionally, through the green meadow. You imagine an art appraiser readying his magnifying glass, only to lower it slowly, wondering what kind of joke you’re playing. At least one friend has suggested that with a little green paint, I could fix that right up. For five dollars at a yard sale in Belmont, MA, it was a steal—the work of an amateur with some skill who didn’t bother to clean up the drip. “My dad painted that,” a boy told me, taking my crumpled dollars. A guy who thought, Eh, somebody’ll buy it. I couldn’t not buy it. This, to me, was Art. Not the perfect bucolic scene of serene sheep with a herder in the distance holding a staff, but a painting unlike any other that needed no signature or authentication. Its uniqueness spoke to my quirky desire for the unloved, the thing left behind. It has a lot to do with why I go to yard sales—on missions of rescuing unmatched candlesticks and books in need of a reader. Pottery Barn houses mystify me. I don’t want to own the coffee table—and certainly not the art—of my neighbour. My neighbour, however, is equally mystified by my love of a sheep painting gone awry. I remember spilling paint once as a seven-year-old in an after-school art class taught by former hippies in their home in Cambridge, MA. I tipped something over by accident—a jar of paint or the colour-tinged cup of water holding our brushes—and the colours spread all over the painting of the girl next to me while she was at the sink washing her hands. As cool as it looked—her painting was enhanced by the spill, I thought—I knew she wouldn’t think so, and I slipped out before the outcry. I lived right around the corner from that house for years, and it’s funny how shame follows you, like the beady eyes of a sheep. Maybe staring at the painting is penance for ruining that girl’s picture. Or it’s a pining for a way of life that resonates with me, however unrealistic: the sheep, the chickens, the farm-fresh milk, and rhubarb pies on the windowsill. More likely though, it’s a selfish love of a piece of art that I, alone, love, dribble and all. I feel a kinship to the collector in whose house hangs Leaving the Paddock, by Edgar Degas, stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, both of us gazing upon our paintings in the same protective way. We share a bond, and perhaps a pang of guilt, that our masterpieces may never be appreciated by another. Jaqi Holland Jaqi Holland is a writer and copyeditor living in Salem, MA, with an affinity for imperfect art and children’s art, particularly paintings discovered at yard sales. She has an M.A. in Writing and Publishing from Emerson College where she works in academic support.

1 Comment

Audrey

2/23/2021 08:02:06 pm

Thank you Jaqi!! I really enjoyed the restful visit inside your mind!!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|