|

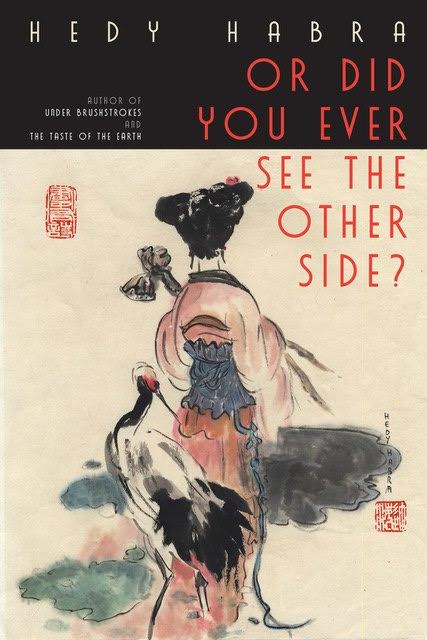

In Conversation with Hedy Habra About Or Did You Ever See the Other Side? Or Did You Ever See the Other Side? Hedy Habra Press 53, 2023 Tell us about the style choice to start every title with the word “Or.” What is the significance of this to you? When I first started using "Or" in the titles, I didn't envision replicating the same pattern in an entire collection. After having published numerous poems with such titles I felt confident in pursuing this style. Since this book was eight years in the making, I did question my choice at one point and wondered what this approach meant to me. I felt that the inclusion of "Or" invited the reader to participate in unraveling the questions raised within the poems and opened the door to interpretations. Since writing is both an exploration of the self and of the world, the word "Or" suggests both the duality within oneself and a poem's underlying meanings. The title of the book, "Or Did You Ever See The Other Side?" hints at uncovering the hidden, unseen side of things, and the title poem sets the tone with a similar question. Most of your work is written in some kind of relationship with art. How did this happen for you? Tell us more about your connection to visual art and why your words depend on it so intimately. I am a very visual person with a passion for art. I love spending time in museums and exploring artists' work in books or online. My mother's paintings covered the walls of the house where I grew up. At a very young age, I used to engage in a dialogue with the characters in the paintings and imagined stories inspired by the scenes depicted that kept evolving with time in a sort of organic way. Delving into the imaginary world of an artwork as well as into an artist's creative process became a habit, which led me to write art-inspired poetry. I feel that brushstrokes, shapes, colours, and compositions are languages that speak to me and impulse me to transcribe them or transmute visual images into verbal images. I usually don't aim at depicting an artwork but rather respond to certain elements of the work that trigger an emotion or memory associations. Most of my poems are persona poems, at times addressing the artist, the characters, or imagining the relationship between the artists and their models. Sometimes verbal images coincide in synchrony with the artwork, but I feel that words should stand on their own, creating a new world. Oftentimes the verbal images provide a sequel to the scene portrayed or another version of the original, adding a new dynamic life to the artwork. As a result, after having written or read an ekphrastic poem, we can't look back at the source of inspiration in the same way because the artwork will retain traces of the verbal images projected onto it in an inter-artistic dialogue. Many of your poems are inspired by or connected to the work of women surrealist painters. Can you tell us more about how and why surrealism speaks to you? I love surrealism because of its connection with the world of dreams and the deeper realm of the subconscious. There is an inherent symbolism in surreal artists' recurrent motifs, which express emotions in an underlying visual language awaiting to be deciphered by the spectator. I feel that by observing such artworks, our memories and imagination are triggered, and involuntary memories arise from the depth of our psyche. I have always had an allegiance to the imagination and find the unusual settings or juxtapositions of surrealism a great source of inspiration. Among the surrealists whose work I admire are Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, Leonor Fini, Dorothea Tanning, and Juanita Guccione. I am drawn in particular to Varo's art to whom I dedicated a great number of poems. Varo was an admirer of Carl G. Jung and one can retrace in her art an alchemical and archetypal quality alongside the exploration of the unconscious through dream interpretation, all of which fascinates me. I had written poems inspired by surrealist artists, including Varo in my previous ekphrastic collection titled Under Brushstrokes (Press 53, 2015). But while this book was inspired by a variety of artists regardless of gender, styles, and periods, my latest book, Or Did You Ever See The Other Side? is for the most part inspired by women artists of diverse ethnicities and nationalities, either contemporary or surrealists. When you visit an art gallery or museum, what other artists or styles do you seek out immediately? I love all styles of painting. I have a great admiration for Renaissance artists and 19th-century Romantics. For a very long time, I was mostly drawn towards impressionists and surrealists but I have been gradually developing an interest in cubism and abstract art as I am learning to appreciate and understand modern art. Are there any artists or art forms you hope to write about that you haven’t yet? I have been broadening my sources of inspiration in recent years, including aside from paintings, sculptures, musical scores, installations, wire sculptures, photographs, collages, TV shows, and movies, but I'm nonetheless open to discovering more artists and new art forms. I have folders filled with collected artworks that piqued my interest without having any predilection for the time being. I am still interested in exploring more artworks by my favourite surrealist artists such as Varo, Fini, Carrington, Tanning, and Abercombie. You are also a visual artist. Can you share something about your art practice with us? How does your own art practice inform your poetry? I was interested in portraiture for a while and experienced pastels then with oils and watercolours. I couldn't dedicate myself fully to art because I was teaching, and taking language and literature courses alongside writing poetry, fiction, and criticism. Over the past fifteen years, I have been learning Chinese ink brush painting on rice paper and have fallen in love with this art form despite its challenges. I have come to enjoy the empty spaces of Eastern art that evoke pauses in poetry, or what is left unsaid. I have been using the free style which requires speed and spontaneity and expresses an emotion akin to writing poetry. For the Chinese, poetry and painting are interchangeable, and I'm happy to have used these skills to paint my books' cover art. Oftentimes, when I have difficulty writing, painting offers me a way of meditating as over a mandala. As I paint, my desire to write returns because by recreating landscapes, figures, and animals, I get immersed in the language of brushstrokes and colours. I wrote a poem explaining my obsession with painting cranes and toyed with the idea of writing a collection of poems inspired by my paintings, a project that might materialize someday. Painting stimulates my imagination and helps me overcome the struggle with the blank page. You have a special affinity for the prose poem. What is it about this form that attracts and inspires you? I love the fluidity offered by the prose poem and the fact that it leads itself to a stream of consciousness, which is ideal for expressing dreams and daydreaming. Prose poems are also an apt form for writing narrative poems because they flow easily without restraints and offer a dynamic movement, especially if the poem consists of a single sentence. When a prose poem responds to a painting I feel that the poem's geometric shape evokes a canvas and its four sides work like a frame. If the poem's language is visual, using verbal images feels as though one were creating an animated version of the bi-dimensional painting. You also experiment with a range of other poetry forms. How do you know when a poem should be a pantoum or a prose poem? Do you set out to create a form and wrestle the words into that structure? Or does the muse visit certain themes or ideas in a particular form? I think that the poem itself dictates the form in which it will come to life. I have experimented with haikus, anaphoric poems, abecedarian, found sonnets, prose poems, haibuns, dialogue poems, pantoums, and most recently ghazals. Some poems come naturally as prose poems in one single breath and dictate the flow and rhythm of the language while others require pauses and breathing spaces. I revise a lot but when a draft lingers for a long time, sometimes months, perhaps for a lack of connectedness in the thought process, I will then try to put it in a form. The constraints of a form force me to be more selective and approach the poem from a different angle. Do you have a favourite poem in this collection? Is there one that was more difficult or challenging to write? Although this is a difficult proposition, I would have to select "Or How Do You Keep Track Of All The Keys You Once Owned?" inspired by The Locked Room, an installation by the Japanese artist, Chiharu Shiota displaying thousands of keys suspended on a canopy of red yarn alongside a few doors. "Or How Do You Keep Track..." encompasses multiple life experiences and meditations around the different meanings of keys. The poem came to life after many drafts and a long gestation since I had so many memories and associations around the word "key." I opted for the anaphoric repetition of keys at the beginning of each line, which enabled me to enumerate thoughts and images in the shape of a decreasing pyramid. This triangular shape made me also think visually of certain key' segments. In terms of difficulty, I think that the pantoum, "Or Can't You See How We're Weaving Ourselves Tight?" inspired by Three Women and Three Owls, a painting by the American artist Juanita Guccione was one of the most challenging pantoums on account of the many possible ways I could approach the poem. I imagined the three women dancing by the beach either as three friends with different personalities or thought they could represent three facets of the same woman seen at different stages of her life. I debated about writing the poem from the voice of an older woman reminiscing about her former selves but also imagined them as friends with different personalities. I opted to alternate the point of view between the first person, the second, the third, and the first person plural. The form of the pantoum befitted this sort of shifting voices that merged at the end into the first person plural. I felt a great sense of satisfaction when it was completed. The poem is still open to numerous interpretations but its writing involved making several decisions while being restricted by a form. If you encountered someone in a café line who didn’t know your work, how would you describe it to them? Give us your elevator speech! I would tell potential readers that I painted the cover art portraying a woman seen from the back, so that we can only imagine her features and expression, and I would invite them to respond to the questions raised by the book title and the poems as they take a closer look at the unseen side of reality. I would also mention that the book offers the option of a double reading experience: to read the poems for the sake of their words and verbal images, then reread them with a renewed perspective after consulting the index referencing the visuals. And I would add that if any of these poems would trigger an emotion, I would be utterly satisfied. What are your plans for your next project? I am in the process of compiling a couple of poetry manuscripts about my childhood and personal memories. Most of these poems were written over many years and were already published but have not found room in my other memoirs in verse. We end up playing so many roles that when we try to recover the early facets of our personality it is as though we were getting reacquainted with our old selves. Many of these poems are also ekphrastic poems that have triggered recollections. I regularly write ekphrastic poetry stemming from the imagination in a magic realistic vein for a future collection. In addition, I should also revise a bilingual manuscript of my own selected poems that I've translated from Spanish and English. and was relegated in a drawer for over a decade for lack of time. I also would love to dedicate more space to complete some unfinished artwork. Or How Do You Keep Track Of All The Keys You Once Owned? keys to unlock one’s buried memories keys to the family cottage you had to sell keys that once opened different-sized locks keys that had to be changed after an effraction keys that yearn for the doors they used to open keys thrown into a deep well, still oozing blood keys to the palaces King Farouk owned in Egypt keys to learning how to deal with oneself and others keys to the meaning of feelings that you kept losing keys to the safes holding papers that ruled your lives keys kept in a jewelry box that must have mattered once keys, lost, forgotten or treasured as a possible come back keys to the wrought-iron patio gate half-covered with jasmine keys that opened the car door that led you straight to the beach keys to dreams’ horned and ivory gates that keep getting mixed up keys meant to reach the heart of a man before he’d change the locks keys you hold in your palm and run your fingers over and over again keys to an old friend’s house who once relied upon you to water her plants keys passed on from generation to generation to reclaim the ancestral home keys that you had to return to the hotel where you wished you’d spend a lifetime keys to all the cars you’ve ever owned and led you through long-forgotten crossroads keys to the office you left carrying a cardboard box filled with what seemed important keys to the wooden-carved secretary your mother handed down to you that held no secret to her keys to the homes you kept leaving, from country to country, from one neighbourhood to the next Hedy Habra After Chiharu Shiota, The Locked Room (2016); solo exhibition: The Locked Room KAAT Kanazawa Arts Theatre, Yokohama, Japan. First published by MockingHeart Review. From Or Did You Ever See The Other Side? (Press 53 2023). Or How Can We Ever Cut Down To The Bare Essentials? He kept retreating from room to room, feeling the weight of all the furniture and mementos staring at him like deceased relatives. It was as though the house wrapped layers of time around him, confining him inside a pod about to burst open. For a while he’d only use his bedroom and the kitchen. He eventually retreated to the sunroom. Its walls lined with bookshelves comforted him as he lay on the wicker couch opposite the bay window. He soon realized he needed fewer meals and only one change of clothes. Feathers seemed to grow out of his bones, filling him with a desire to embrace the movements of the wind. He tried to get rid of plants, of his archived papers, of the photos that couldn’t find their place in the abandoned albums. He sorted out the books he knew he’d never read or reread. Finally, the day came when unable to break all ties, he clung to his tabby, the photo of a woman, a purple-lipped cattleya, a few books, anything he could hide under his strong wings, slammed the door and left. Hedy Habra First published by The Bitter Oleander. From Or Did You Ever See The Other Side? (Press 53 2023).

2 Comments

Brent Masters

5/17/2024 12:03:49 pm

This is fantastic! I am truly inspired by this dive into the dream/reality balance and will be enjoying Hedy Habra's work! She has several other published works as well! Thank you for the interview.

Reply

Susan Azar Porterfield

5/23/2024 03:45:28 pm

Wonderful interview. Inspiring.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|