|

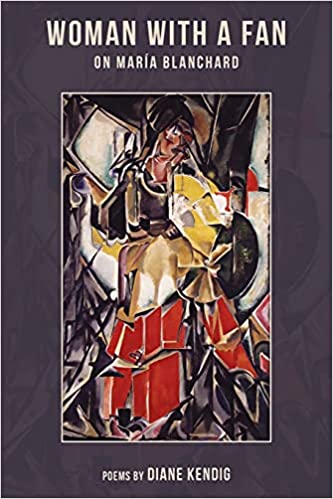

Woman with a Fan: On Maria Blanchard Diane Kendig Shanti Arts Books, 2021 The Ekphrastic Review: How did your relationship with the painter Maria Blanchard begin? Diane Kendig: I really love the poet Federica Garcia Lorca, and one day in the 1980s, I was re-reading the collection of his prose writing. I was struck by the first, very short essay, which I hadn’t recalled reading before. It was a funeral elegy for Blanchard, whom he really didn’t know. He gave the eulogy at the request of her friend but looked up facts and at least one work by her and gave a very, very personal eulogy. Here it is in Spanish and English: http://mujeresenelarte.blogspot.com/2009/02/elegia-maria-blanchard-federico-garcia.html Tell us, why Maria? Of so many women artists, what was it about Maria that meant a book of poems for you instead of just one? Well, really, it started with just one. After reading Lorca’s elegy, I imagined what her life must have been like, disabled, and how that might have affected her mother’s distanced relationship to her. The poem was biographical, not ekphrastic at all. I was wrong about so much in that poem, which I have since revised. I was trying to find her artwork and couldn’t, but I then found a reference to her relationship with Rivera, and that really set me off and produced the second poem. I never planned a book. It just grew over 30 years. I was encouraged by Michael Northen, the editor of Wordgathering, to write some prose about her, and I just wrote a poem or two about her art each year, and really, there it was. I am not a poet who gets a theme and knocks off a book. And then I found Shanti Arts with Christine Cote, who is so much wiser about art reproduction than I, who has a wonderful publication and books and a gallery and anthologies. When I found her as a publisher, I realized this book could be. What sets Maria's art apart, for you, from other cubists of her time, from other painters in general? I had been writing poems about Frida Kahlo in the years before and found her relationship to Rivera to be so problematic for me, who was raised never to be a man’s handservant. Then, I read how Blanchard loved him first, shared a studio with him, but she would not wait on him the way Kahlo did. When he tested her, whether consciously or not, she just dug in and focused on her art. And that, that, is what set her apart. She worked with men who had women waiting on them hand and foot, and she worked with them as an equal, as an artist. She always worked first on her art. She had to earn a living, and she taught too, and she supported half her family, but art came first, even when it meant penury. I had been there, too. When cubism came along, she studied it and produced a lot of it, and very good, though her previous training, like theirs, was classical: portraits, a mythological subject. Then, then she took this most classical theme, a woman holding a fan (look that up: centuries of it in every culture, painting after painting) and she made it CUBIST and SPANISH, very Spanish. And what is more Spanish than a woman with a fan? Hers is amazing. Two themes that surface in Maria's work and your work about her are her gender and her physical disabilities. What can you share with your readers in advance about Maria's struggles? I’ve mentioned both above. She was born with kyphosis, or as everyone says, “hunchbacked.” Lorca said it was the first thing everyone told him about her, before he saw her art. So me too, the first thing I learned, from his eulogy. And during her time, everyone said it was because her mother fell from a horse during pregnancy. Everyone said that. I wrote it. I am appalled at myself. I was set straight by my friend Maria Bonnett, a nurse practitioner who said, “No way.” And then, in the latest documentary on Blanchard (by film maker Gloria Crespo), a doctor puts the myth totally to rest and says the condition was not caused by a fall from a horse. Puh-lease. And he discusses the condition, what does cause it. He provides x-rays. There was a tradition—Maria said in Spain, but I have found accounts of it here in the U.S.—that you’d win the lottery if you touched your ticket to a hunchback, and she faced being chased down the street by people clutching their tickets. So in addition to the physical difficulty of having the strain on her body, she had the social stigma. She said she fled to France because of it. I don’t know that she experienced less stigma there. As for gender, well you have to look at the work of the Spanish feminist art critic María Jose Salazar, who has worked for decades to gather and catalogue Blanchard’s work because she believes its inordinate range and quality speaks for her itself. And Salazar attributes the relative lack of fame Blanchard received in her lifetime to gender inequity. In her 20s, her work won over Rivera’s in a major competition. And at her death, someone took one or more of her paintings and erased her name from it, overwriting it with the name of the famous painter, Juan Gris, who had also been one of her best friends, knowing it would bring more money that way. Tell us about your quest to see Maria's work, and about seeing it for the first time in Spain. I had been to Spain as a student in the 1970s, but none of her work was public then. Once I found her work, in the mid-1980s, I had just obtained a full-time academic position at a small liberal arts college. The librarian helped me find one book with some of her paintings on interlibrary loan, and I was so excited to send for it. But when it arrived, in photocopy—black and white photocopy—the paintings mostly looked like Rorschach tests. I felt disappointed in my very body. In the mid-1990s, my husband and I made a few trips to Europe and eventually to Spain. On entering the Reina Sofia Museum (which is basically the Prado Modern), I was looking for where Guernica was when Paul spotted Blanchard’s name and the painting, Mujer con abanico. I had no idea she was there. I tore up the steps. She was above Picasso!! She was next to and bigger than Rivera! She was magnificent! Later, I went to the gift shop, where Salazar’s complete, 700-page catalogue of Blanchard’s work was on sale with its huge colour prints and its great biographic info. I bought it, and I carried it on the plane, held it on my lap the whole ride home, and wrote from it ever after, one painting at a time. Tell us how you came to ekphrastic poetry. I’m not sure. I for sure didn’t know the word “ekphrastic” and didn’t know it was a thing. I know I loved Paul Klee’s Pastoral at the Cleveland Museum of Art, and I loved how Klee had said if he couldn’t be a painter, he’d like to be a poet, and I loved his titles. I read his diaries and felt his connection to words--Twittering Machine. The Poets League of Greater Cleveland (now defunct) had several programs presenting poetry relating to art (“Poetry: Mirror for the Arts”), and my Klee painting poem was used for one of those, with an epigraph by Kitaj, an artist who studied in Cleveland: “Some books have paintings, and some paintings have books.” Yes. Then I did the Frida Kahlo series. Even while I was writing Blanchard poems, I wrote a long poem on all the Judith of Bethulia paintings. Another Klee the CMA has bought and hasn’t exhibited yet. A chilling one. When I am stuck—and I am always getting stuck—translating and ekphrasis-drafting sort of suck me out of my stuckness. Tell us about your ekphrastic process. How do you approach a painting, or a poem? How does the inspiration and transformation work for you? Honestly, I am not quite sure. So let me just tell you about what I used for the Blanchard poems. After the first two Blanchard poems, which were biographical only, I wrote my first of the ekphrastic Blanchard poems, “Oriental Caprice,” as a commission piece). “Oriental Caprice” was requested by a former student of my sister, who had just died at age 49 of a long battle with cancer. My sister was her friend, and my very best friend, and Blanchard painted that very uncharacteristic (for her) work out of friendship. I felt that I wanted each poem to have what that poem had: something about the art, something about Blanchard herself, and some connection to me. In a lot of the Blanchard poems, there is a very personal tug at my heart going on that the reader may or may not be aware of. For example, “Portrait of Regina Barahona” is Blanchard’s portrait of her niece. I had a niece that I helped to nurture from her adoption, through the two years of my sister’s cancer, and then, after she died, the guardians cut off most of my visitation. As an aunt there is nothing one can do about that, and I haven’t stated it in the poem, but I know my experience is underlying that poem. And there is something like that in each of the poems. I also tried some forms, a Welsh form and a 17th c. form used by Andrew Marvell that I can’t find anywhere else. (And his was an ekphrastic poem about a child, as mine is, “Child with a Toothache.”) Forms suck me out of my stuckness too, and wow, form plus a painting, there is so much firing in my head and heart, I can’t stay stuck. Read one of the Woman with a Fan poems here.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|