|

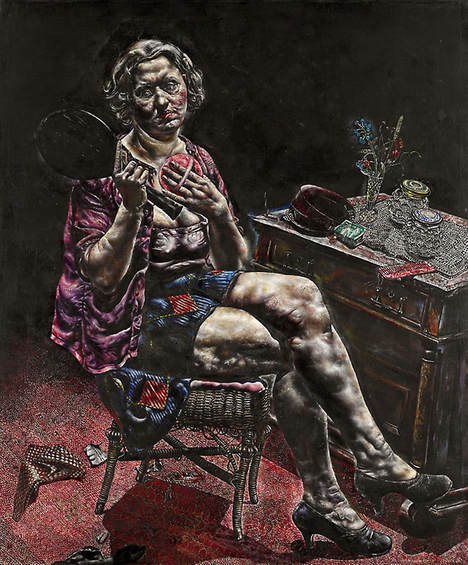

Into the World There Came a Soul Called Ida I. Ida mourns her ruin, the truth of it rendering her hand-mirror so heavy it tilts away from her. She cranes her neck to keep her face within its circle. Her powder puff is not so different from the daub-cloth used to soothe the dying. There, there, now, she tells her flesh. Go easy. Her hands upon herself are strong, matter-of-fact. Before moving to the city, her people worked the land. In the meat of her forearms, in her knuckles, we see the arc to the chopping block, the squeeze of teats, the lifting of bales. Now, she labours for a different kind of bread. The bills and change upon the dresser-top hint at what—waitress, bar girl—someone who must force a smile with those as tired as she and turn the rusty crank of sociability. II. [I know Ida’s look from witnessing the ruin of my once-beautiful mother, from watching my own ruin. There was a time when I taught, confident in my body, certain my ass carried as much information as my words. Now, each year reduces this arsenal. Even as I expand, I shrink in the eyes of my watchers. I yield to the mirror, sad, heavier in my bones. My fifties unfold to the scrape of the bulldozer, the old house brought down along with its roses.] III. Ida surveys her landscape of cellulite. The bright light lifts moraines—years of forkfuls in diners, of solitary meals. Her breasts droop to meet belly-folds. She tucks time into their shadowy involutions. Skirt, shirt, hair, all waves, ripples spreading from the ground zero of her birth. She must be heading out, otherwise, her shoes would be off. They are not comfortable, their spindly heel not broad enough to bear her haunches down the long furrows of the day. Something outside herself demands this concession—rent, groceries, the tooth aching in her jaw, her worn underthings, greyed from repeated washing. She must keep those damp pumps on. IV. [I too would rather spend the day in yoga pants—the same pair silk-soft, split-seamed, drawn about me like tender arms—but we haven’t come to that yet, have we, Ida? Not yet the muttering old lady on the bus, the cautionary tale.] V. Each object about her whispers its provenance. Ida mouths their stories like church-creed. The cut glass bowls, not from her own wedding but from a stranger’s, floating up at the Goodwill after an estate sale, or found, just barely chipped, in a box on the curb. The dried flowers from an empty lot from a gone season. The scarf from a long-ago white elephant exchange. To another, all would be trash, garage-sale goods so blown that one dare not look at their owner. VI. [One day, my children will steel themselves and empty my house. Some objects will speak loudly enough to save. Others will remain mysterious, unable to advocate for themselves from their decay. The rooms will quickly empty. Ida’s wicker chair, her split dresser, mine, will tilt on the landfill, singing mournfully until buried.] Devon Balwit Devon Balwit teaches in Portland, OR. She has seven chapbooks and three collections out or forthcoming, among them: We are Procession, Seismograph (Nixes Mate Books), Risk Being/Complicated (a collaboration with Canadian artist Lorette C. Luzajic); Where You Were Going Never Was (Grey Borders); and Motes at Play in the Halls of Light (Kelsay Books). Her individual poems can be found in The Cincinnati Review, The Carolina Quarterly, The Aeolian Harp Folio, The Free State Review, Rattle, and more.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|