|

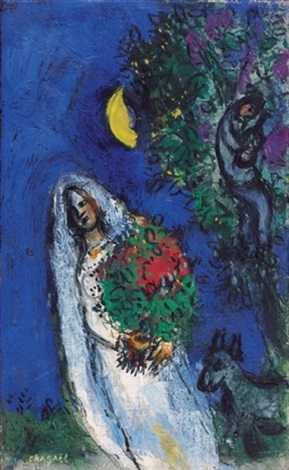

La mariée à la lune

My father decided to use his inheritance to buy my mother a Chagall. I figured this would remain another of his unfulfilled schemes. He’d fly to New York or London for an auction, get distracted five minutes off the plane, and come home with tourist bric-à-brac rather than a painting. Even if he only went as far as the Toronto auction houses, driving our car down to Bowmanville and taking the GO the rest of the way, I could divert his attention easily enough with the sarcophagi at the ROM or the Hockey Hall of Fame or betting him he couldn’t climb all the stairs of the CN Tower in one go. But then he told me you could buy art on the Internet, and I started to worry. “Look," he said, having dragged me into a cupboard under the stairs where we had kept the telephone, before it was disconnected for non-payment. “Which do you think your mother would like?" He passed me a book. Flying goats. Violins. Elongated women. Spheres of flowers in the sky above la Côte d’Azure. And all that blue. My mother loathed blue. We lived in a house bereft of blue. No blue plates, no blue sheets, not even blue jeans. We didn’t buy Rice Krispies because of the blue box. We filled up at the PetroCan because of the blue on the Esso and Ultramar signs. There was no way my mother would want a blue painting. I hesitated and my father grabbed the book back from me and held it to his chest. The plastic library cover crackled in his hands. He must have used my mother’s card to take the book out; I’d hidden his card because we couldn’t handle any new overdue fees. “Your mother’s happiness will be like an atomic bomb," he said. “Boom." I might have only been in my second decade alive, but had I received the money, I would have used it in a less frivolous fashion. For instance, we’d had an estimate for roof repair next to the microwave for months. And most of the banister through all the three floors of the house had rotted through. Also, each winter the furnace took longer and longer to spring back to life. Plus the electrical in the house was original and ungrounded, except for the kitchen, redone on its own circuit breaker by a friend. We needed to use this money responsibly, as our only other income was the honorariums my father received from his few corporate board positions and some dividends from a few stocks he benignly neglected. This miniscule sum did not pay for the lifestyle to which he was accustomed, even out here in the sticks, with nothing to spend money on. “We’ll have to keep this a secret," he said. “From your mother. This isn’t a surprise you are going to ruin. Not this time." He dropped the book and grabbed my arm. “You aren’t going to ruin this for me?" he asked, grip tightening. “Are you?" I shook my head. “Promise me," he insisted. “Promise me." I promised. At dinner, my father slammed his plate onto the table. “Cookies," he announced. My mother didn’t look up from her book, an orange Penguin with pages loose in their binding. “There may be a box in the pantry," she said, chewing from the edge of her mouth. “I’d finish your dinner first." “I mean computer cookies," my father clarified. “What about them?" My mother disinterest was palpable. “We should delete them every day. Clear the cache. Like a garbage bin." My father mimed emptying a wastepaper basket into a larger bin and knocked a fork to the ground. “I don’t see the harm in that," my mother agreed, head still down in her book. I told her that the routine expunging of the cookies and cache would mean having to enter her library code each time she went to the library website since the browser wouldn’t save the twenty-two digits in memory for her anymore. Only then did she look up from her book and frown at my father. “That," she said. “I wouldn’t like to do that." “No. No problem," my father replied. “Already thought of. Already solved. I saved a text file on the desktop. Copy paste every time you want to go to your library account. Almost no additional time whatsoever." My mother thought about this. “Edward Snowden," my father said warningly. “I suppose," she finally decided. “For safety." “And that," my father told me later, “is how she won’t be able to search the history and see what we have been up to." I disliked the way he included me in his we. I decided an indirect approach might yield results. Thus, I pointed out each creak and hum in the car, wincing theatrically as we drove over speed bumps and commenting on the state of the shocks. I kicked at the back shed until it collapsed and then asked him where he was going to store the lawnmower. I grabbed calculations off the bank website about how much money one needed to get a professional degree Medicine/Dental and presented the printed-out spreadsheet to him. “I don’t want to be a dentist," my father said. “Do you want to be a dentist?" he asked. “That seems rather," he thought for a while. “Pedestrian," he decided upon. “I always figured your work would be more substantial, artisanal farming or becoming an apiarist. Or an explorer." His eyes flashed. “You would be like Vasco da Gama searching for the Fountain of Youth." I didn’t bother telling him it was Ponce de Léon who searched for the Fountain of Youth, not Vasco da Gama. On Monday, I took his SIN card from his wallet and called Revenue Canada. Although the money had come to my father via a cousin, I guessed my father was still liable for paying some sort of inheritance tax. Obviously, my grandmother hadn’t left my father a quarter cent. But the cousin who’d inherited the lot felt sorry for us and had passed a chunk of the liquidated assets along to my father because, other than my grandmother, everyone in my family loved my father. He played the family mascot, an idiotic puppy, and made them all feel better about their own Ponzi schemes and tax evasion and the Rosedale branch who had lost all their money in Bre-X and Nortel stocks. They liked that we were country in that we lived near Peterborough and didn’t have season passes to the symphony and Soulpepper the way they did. They liked having people poorer than them in their periphery. I couldn’t get a straight answer about the inheritance tax, although the gentleman with the thick West Indian accent did get very snippy at me regarding the back taxes and fees accumulating exponentially on my father’s account. I scribbled down some of what the civil servant said on a serviette, then hung up the cellphone before we could discuss repayment plans. To find my father, I followed the orange extension cord from the one grounded plug in the kitchen back to the understairs’ nook. He sat, cross-legged on the floor, with the laptop balanced on his lap. I started to wave the napkin of figures in front of his face but he pulled me down next to him so I could look at the computer screen. “See," he said. We both couldn’t sit inside the cupboard, so I sat on the uneven marble tile of the hall. He turned the screen towards me so I would see more than the reflected glare of his face. The website listed a variety of Chagall’s available at auction or for purchase from private collectors. Scrolling down to the bottom were some relatively affordable lithographs: low five digits rather than high sixes or, the more worrying, Serious Enquiries Only, no price listed, ones at the top. I found a small lithograph, second to the end, in ivory and red and black. Splotches of dark leaves and red currants, petals, hints of birds in the upper right corner. I moved the mouse onto the image to show my father. The painting matched the décor in the second floor powder room. My mother could hang it up there. “Oh no," my father said. He shook his head so hard his tie rose up and smacked his sternum. “Not that. Too puny. Not grand enough." He scrolled back up to the top. The very top. “That one. Number one. Thinking." He knocked the side of his head with his fingertips. “Must be the best if they put it first." Serious Enquiries Only. A painting. Not a lithograph or a reproduction. A full-on painting of a large blue bride in white, holding a red bouquet of flowers under a yellow crescent moon. Plus a man in a tree with a violin. Plus a goat. Of course a goat. I mumbled a dazed question about picking such a painting up. “Pick up?" He sounded disgusted. “They ship. Fancy courier. Insurance. All ship-shape, top-of-board." “Oh Marty," I could hear all the relatives say when my father told them this story, inevitably after the painting got lost or stolen or strayed or that the whole thing had been an Internet scam and no Chagall had ever been forthcoming, all the money squandered, our house’s shingles still shedding, termites dining on the original woodwork, our car’s transmission having dropped out somewhere by Fowler’s Corners on Highway 7, me in dental school on student loans, and my father in prison on tax evasion charges. “Always such a gas." “Friday," my father said. “Guaranteed delivery by Friday." My mother cried on Friday. She wept like an open tap on Friday in the entryway, surrounded by box cutters and Styrofoam packaging. “Oh Marty," my mother cried. “Oh Marty, you remembered." “I did," my father said. “I remembered. All by myself. Just me. Remembered." “Oh Marty," my mother cried again and again. And there I stood, at the edges of my parents’ lives. My mother crying, my father. I had to breathe through the clenched teeth of my smile to keep from crying too. Not out of their shared happiness though. I hated being wrong. Meghan Rose Allen Meghan Rose Allen has a PhD in Mathematics from Dalhousie University. In a previous life, she was a cog in the military-industrial complex. Now she lives in New Brunswick and writes. Her work has appeared in The Fieldstone Review, FoundPress, The Puritan, and The Rusty Toque, amongst others. One can find her online at www.reluctantm.com.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|