|

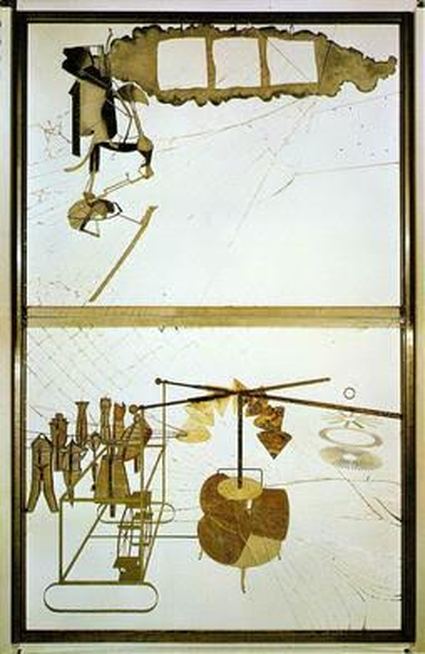

Looking in the Glass As Robert stared at Marcel Duchamp’s The Large Glass at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the image of the nude body of Robert’s married lover Cheryl kept distracting him and slipping into his thoughts. ‘Stop thinking about it!’ he said to himself. The thought of their affair was like a drug. He closed his eyes and said a few times to himself: ‘Stop feeling her body, stop thinking about how you want her, stop the yearning, let go of the pleasure. Look at The Large Glass!’ His inner turmoil and efforts to dispel Cheryl from his mind resulted partly because Robert’s brain had three other forces demanding his attention: God, Maryanne and his thesis advisor. Both the seminary life that he had previously pursued before his present studies, and the need for the spiritual in his life, had not lost their appeal. But the image of Maryann, the girl he met while studying at the seminary, intervened as well. “I adore you,” he could hear her saying, “because you’re a good person” with such “high morals,” pursuing theology and philosophy to help people. Maryann did not drink or smoke or take drugs, and refused to have sex before marriage, thus a stable choice for a man of the spirit. But after he switched to his graduate program in music and met Cheryl at a party, he was mesmerized by Cheryl’s rebellious nihilism, love of art and music, and not least her adventurous love-making. Robert started to ignore Maryann, did not return her calls, and made up excuses while Cheryl introduced him to the sybaritic life, even though he believed that these constant carnal thoughts and lascivious habits of her life-style were not the healthiest path to spiritual bliss; and, yes, he wanted spiritual bliss too. ‘Nothing wrong with sex,’ he told himself, ’but my god, take it easy, boy! And remember, you fool, she’s married.’ More than once, he screamed to himself, ‘What are you doing?’ When he shifted to his spiritual state of mind, which, without either woman present, was easy to do sitting alone in this room facing The Large Glass, at least for a brief period, so easy that the work seemed to make a little more sense; but he couldn’t articulate why. Duchamp was an atheist, Robert knew, but Duchamp did believe in some kind of spirituality, possibly theosophy, and his copy of Kandinsky’s On the Spiritual in Art he filled with notes. Perhaps The Large Glass had a group of spiritual symbolic triggers that were affecting Robert somehow on an intuitive level. Unfortunately, he couldn’t hold on to those moments of communing with the infinite long enough to stop the flood of images and emotions from Cheryl’s enticements and the titillation of her soft and warm body. The expectation of sharing a bed with her tonight was driving him so mad he couldn’t concentrate. And he needed to concentrate because there was a third force needling him, his thesis advisor. Somehow he had to determine the connection between The Large Glass and the composer Liszt. Find the link with The Large Glass, his advisor said, and you’ll have the topic for your dissertation. For two hours he had been looking at it, staring at every aspect, and still he could not understand what The Large Glass or Duchamp had to do with Liszt or his music other than Duchamp and Liszt both had less than satisfying relationships with women. Nothing else was coming to him. There were plenty of interpretations of The Large Glass and he had tried to read all of them, though his advisor had pre-warned him that research would be of little help, since the interpretations often did not agree with each other. The Large Glass, she said, was the best way to understand his topic. ‘Really? Not so far.’ And this was his third visit. ‘What was she thinking? What would a work completed in 1923, thirty seven years after the death of Liszt, by an “artist”—he apologized to Duchamp who hated the word—who only wrote a couple of pieces of music and created very few works of “art” and always preferred to play chess, have to do with Liszt? Who even knew Duchamp wrote music?’ Regardless, he had to come up with some kind of explanation before dinner because she wanted a topic. Otherwise she had threatened to drop him. What he had written so far, she said, had not captured the true Liszt. “Do you understand the man at all?” she growled in their last meeting in a tone that would diminish anyone’s confidence. The Large Glass, she warned him, would be the final catalyst. ‘Really? This work? This nine foot strange amalgam of wire, dust, paint, foil, cracks, and varnish? ‘Let me go through it again,’ he said to himself, then repeated the same ideas he had continually mulled over for hours: Duchamp said The Large Glass depicts the erotic encounter of the “Bride” in the upper glass with the tiny figures of the “Bachelors” in the lower plate, the “Bachelor Machine.” One writer thought the whole work was a humorous exploration of systems of philosophy, physics or mathematics because of the mechanical and mathematical stuff going on in the lower pane. Others saw the “Bachelor Machine” as a conceptual depiction of the punishing of celibates who were frustrated by the inability to reach the “Bride,” entering the machine to satisfy themselves. The “Bachelors” of the lower pane were so tiny compared to the “Bride” in the upper pane that it seemed as if many of them were necessary for one of them to succeed in overcoming the devices and reaching the single “Bride.” Robert could feel the bachelors’ frustration implied in the barrier between the upper and lower panes, connected only by the cracks caused in an accident when the work was moved. I like the cracks, Duchamp said, now it’s complete. Robert had to admit the cracks somehow fit. Was that the universe at work? He kept reminding himself what Duchamp said about retinal art. Go beyond your eyes; see “with the mind,” not the eyes. * As he sat there in the last hour “with his mind,” it occurred to him that perhaps his advisor was not only interested in an interpretation of the art work, but in Liszt’s experience with women and other artists, particularly when Liszt traveled to Italy with his lover, the married Countess Marie d’Agoult. On his Italian journeys Liszt did view many art works, but one painting, the 1504 painting Lo Sposalizio of Raphael in the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, especially interested Liszt. The painting depicts the wedding vows of Mary and Joseph in front of a chapel. The design of the work, its ideal three-dimensional perspective, and the serenity of its tone, were a revelation to Liszt. It so fascinated him that he pondered it for a long time, entranced both by the mastery of technique of Raphael, but also the potent expression of the spiritual. It was to Liszt such a perfect balance of the spiritual and the aesthetic that it inspired him to compose a piano piece, Sposalizio, in order to say musically what he felt from the experience and the work. Liszt’s Sposalizio was another catalyst for Robert and proved that his advisor may indeed have a plan. When Robert first worked with her, she asked him to listen to, analyze, and write a summary of his reaction to Sposalizio. Robert wrote that in three carefully constructed sections Liszt tried to capture the beauty and feeling of a holy relationship. In effect, Liszt composed a musical mirror of Raphael’s design and reverent homage to the holy wedding and to art itself. Recalling this discussion with her when he summarized Sposalizio, Robert then took the leap he thought perhaps she wanted him to take. The reverence and structure of Sposalizio were not only an indication of Liszt’s respect for the holy event and for Raphael’s Lo Sposalizio, but of a deep need in Liszt’s life for spirituality. Expressing spirituality musically was his way of being spiritual when he could not manifest it in his life. Clearly Liszt saw in this holy marriage painted by Raphael something quite different from his own illicit relationship with Marie, who ran off with him while still married. Their passion and fascination faded when Liszt constantly toured and left her with three children he fathered, two of whom would die tragically before they reached thirty years old, an event that brought guilt as well as sadness for the rest of his life. As Robert looked through The Large Glass thinking about Cheryl and his conflicted feelings—‘do I really want to keep up this sexual escapade with Cheryl?’—he seemed to look through it and yet be a part of it in his reflection, he began to connect Duchamp’s work with Liszt’s numerous attempts at relationships—many superficial, almost all only based in lust—and appreciate why Liszt’s creation of Sposalizio could be cathartic. Liszt always wanted to be the artist-priest, spiritual and ascetic, but he failed again and again throughout his life, never reaching the “Bride” of The Large Glass. Instead he achieved an ignominy from the failure of so many relationships before and after Marie. The flesh would always beckon him, he would hesitantly say yes, however much its pleasure brought consequences. Robert looked at a photo of Lo Sposalizio on his phone for a few minutes, then closed his eyes and placed its image beside The Large Glass and its “Bride” while listening to a performance of Liszt’ Sposalizio. All of it coalesced. Purpose and technique conjoined with content. If only art could be life, Liszt and Duchamp must have thought, and Robert agreed. If only he could free himself from these feelings about Cheryl. Raphael’s wedding of the Virgin was the perfect model, and the relationship a holy relationship, but Liszt knew that he would never come close to it in his own life; his own relationship with Marie was not pure, not proper, not honest, and filled with more and more conflicts, worms eating away from the inside, a sign of problems to come. As Liszt had studied Lo Sposalizio of Raphael in Milan, Robert believed that Liszt realized that the piano work Sposalizio was for him not only a music of celebration and spiritual yearning, but also one of regret and then shame, because he could not restrain himself from continuing his torturous needs and escaping the trap he himself had built. After Marie, Liszt became involved with another married aristocrat, the Russian Princess Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein, but this woman had high spiritual and musical expectations for him, convinced him to stop touring and concentrate on composition, went to enormous efforts to divorce her husband but still, according to her own testimony, Liszt could not restrain his addiction for other women—Liszt had a notorious fling in Weimar while Carolyne was trying to legitimatize their relationship—so Carolyne withdrew and declined to marry him. In the years following that day of rejection in 1861, coincidentally his birthday, in a period when he lost two of his children, with so many signs that he was not leading the life he truly wanted, he finally was able to make a more determined turn toward the spiritual. He took a small apartment at a monastery in Rome, and was ordained. After 1865 people called him Abbe Liszt, his turn toward the spiritual finally taking hold. As Robert analyzed these biographical details, where the themes of marriage and dysfunctional relationships alongside Liszt’s need for a spiritual vocation constantly appeared, Robert had an epiphany. He realized that the themes of marriage and relationships were expressed in many ways in Liszt’s work, Sposalizio expressing the holy and perfect model of Raphael’s Lo Sposalizio, themes also possible in The Large Glass. But there were other equally significant expressions. Just prior to the time before he knew that Carolyne would not to marry him, Liszt composed Mephisto Waltz No. 1, a piece that expressed the other aspect of his character that had so often derailed his personal life and was clearly not evident in Sposalizio. Mephisto Waltz No. 1 painted a musical interpretation of a section of Nikolaus Lenau’s Faust, a poem of 1836, in which the Devil performs on a violin to cause salacious havoc at a wedding feast, driving Faust to a seduction that he had refused to do initially but finally relents and runs off into the forest with the innkeeper’s young daughter. Once again it was another musical picture of a wedding, but on this occasion, it was not a holy affair. Instead Liszt unleased one of his most flagrant depictions of lust and abandon, an unrestrained evocation of how the Devil can trap men and women with his lurid and bewitching ways. Listening to Mephisto Waltz No. 1 after Sposalizio was for Robert almost a frightening experience, like entering two conflicting realms of existence, as if he had crossed back into Dante’s Inferno after Paradiso. The aggressive, throbbing and unrelenting 3/4 rhythm of Mephisto Waltz No. 1 draws the listener on an exhausting and out of control train ride, with no relief, luring her or him into a state of frenzy that appeals to the senses, and creates by the seductive sounds and melody a rush of hormonal, hypnotic energy, like an aphrodisiac under whose thrall no one has control. The weird fact, Robert thought, as his own inspiration for his topic now came to life, was that Liszt, even in his late period, when he was composing other spiritual works such as the oratorio Christus, could not leave this Faustian theme alone. Three more piano interpretations of the Faust story appeared, all called Mephisto Waltz, all different, but all full of conflict, unusual harmony, wild interludes, and strange sounds, as well as the Faust Symphony based on Goethe’s Faust. As Robert listened to Mephisto Waltz No. 1, still staring at The Large Glass—which, not surprisingly, in light of his advisor’s advice to view it, also could be interpreted as a Faustian tale—still looking at Lo Sposalizio of Raphael on his cellphone, he for the first time experienced by means of Liszt’s life and art how powerful was Liszt’s ability to express these two contrasting sides to his character. Robert could feel in Liszt’s struggle the pain of never fully honoring any relationship due to an almost feral pleasure in succeeding in new conquests and yet desperately wanting to overcome the forces that plagued him. As for The Large Glass, the “Bride” awaited and Robert remained still one of the “Bachelors” hungering for fulfillment that only the “Bride” provided once he had passed the spiritual tests in the lower regions and left behind the wild ride of Mephisto Waltz No. 1 with Cheryl and came closer to the purity of Sposalizio and Lo Sposalizio in his relationship with Maryann. One fact was clear: He now felt ready to have dinner with his advisor. D. D. Renforth Renforth has published fifteen stories and poetry in 2016-2017. Renforth’s long poem (253 lines), “Prometheus Laments” is forthcoming in the Straylight Literary Review. Renforth graduated from the University of Toronto (Ph.D.), but also holds an ARCT from the Royal Conservatory in piano performance and was given a scholarship in art.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|