|

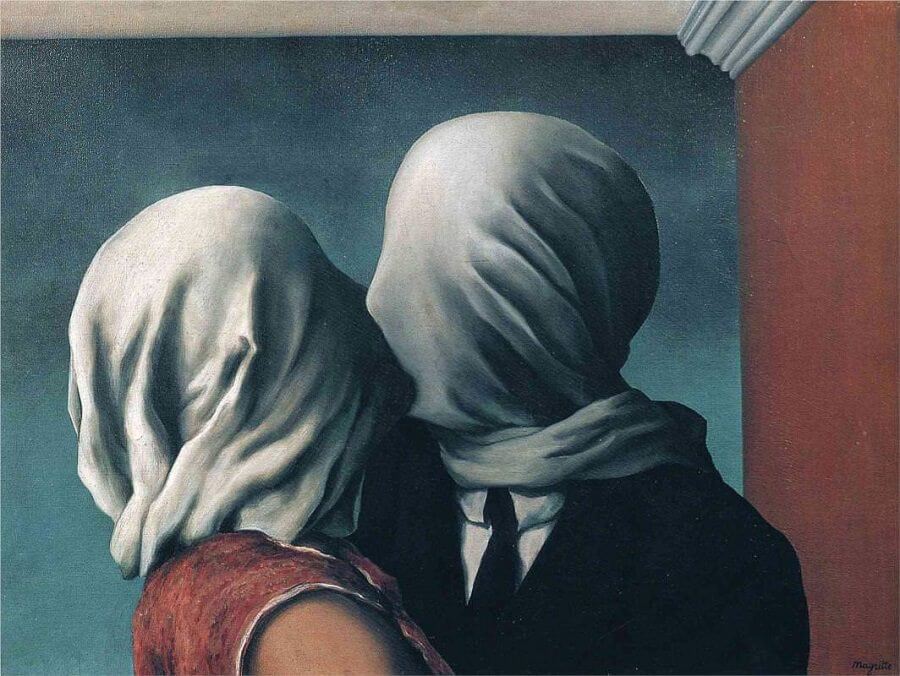

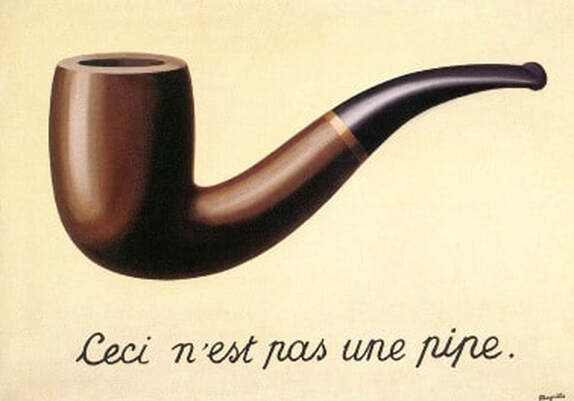

Madame Magritte's Locked Door Leopold was smitten by the comely, demure milliner who ran a little shop in an alley off the Rue des Moulins. In the café near Lessines’ old town square, his well dressed friends would comment whenever one sat down to chat donning a new hat made by that young woman, Regina. Clever, so he thought, and most unlike him, he boldly offered to deliver a bolt of lining cloth and a few rolls of thick ribbon from his father’s storehouse to her cluttered workshop behind a small showroom displaying her hand-made chapeaux on top of painted plaster heads. Sizing him for his first bowler, in vogue with most men of the day; the back of her hand touched his flushed cheek, he thought he felt her soft lips brush his ear as she playfully dangled her measuring tape against the bridge of his nose. Regina was happy and a bit surprised the day he offered her the prospect of security, of finally getting away from her father to become the lady of a fine brick house by simply agreeing to wed her shy, eager Leopold. Lost in the excitement she never stopped to think that soon to be Madame Magritte could not be the permittee of a little hat shop. Once they were wed; her antique felting machine and stretched out pelts, glass vials of tincture, her wooden chest of tools, rabbit fur scraps, a box of pheasant feathers and the heads of six wide-eyed mannequins wearing rough-stitched, unfinished hats were put away in a slanted attic space with a small gabled window overlooking the stone bridge that spanned the River Sambre. Regina nurtured and enjoyed her three boys, who, she once confided to a friend, were each begotten on a Friday eve; the night of the week the men would meet at La Fée Verte. Leopold would stagger home, trudge up the stairs, stumble into their darkened room and drop heavily into their conjugal bed, reeking of absinthe and tobacco. His soft voice turned ‘to a coarse grumble. His tailor's adept hand, a crude cudgel impatiently flailing beneath the bunched up skirt of his tense wife’s long nightgown. In silence, she lay awake next to her dizzy spouse, remembering her cruel father, who, on certain Tuesdays, from the ale house soused, would curl up next to his daughter in her small bed. His besotted presence pressed against her close, he’d fall asleep and snore, a small panicked girl pinned-down beneath his limp, draping arm. Soon after Raymond, the youngest son was weaned a morose cloud seemed to settle over Regina. Her coquettish charm, artful millinery skills, the pride she had in her small shop, were locked away, long forgotten up in the slanted storeroom. The boys that were borne out of her womb now cowered scared, staring at their mad mother from behind the skirt of a new nurse. Regina took no comfort from pipe smoking Parisian doctors discussing mercury vapor and Mad Hatters* in the hall outside her bedroom door. Nor did she gain any relief from chanting priests waving crosses and tossing droplets of holy water at her, who were sent in to somehow calm her. René and his younger brothers watched their wan mother slowly waste away. Sad midnight cries, her hollow eyes, a retching overdose of hemlock, and the slicing of her thin wrist with her favorite pair of shears, had left Leopold with no recourse, but to have her locked in a sparse room whenever left alone. Not just to keep her from more mayhem at her own desperate hand; but also knowing the need to be discreet, to defend the family name from any talk of scandal on the street about a raving mad Madame Magritte. Her back to him, sleepless Regina sat bent over, head in hands, in her ornate wooden chair. Leopold placed a shiny green apple, pewter pitcher and a copper basin atop the shapely legged table, and set a clean chamber pot on the floor next to the door. He backed away, firmly closing the heavy portal, hearing a clack as it latched and a click as the key turned in the lock. Then slid shut the iron hasp he had the blacksmith forge, just to be assured she’d be kept out of harm’s way. While Leopold took the boys to visit their grand-mere, their carriage to return later in the day. Not knowing why, Leopold brought back a slice of the mince pie Regina used to savor. He was shocked to find her bedroom door unlocked; and not hearing faint sighing, her tortured crying, nor the sound of soft soles of slippers shuffling across the floor, got his heart to beating faster than that moment he first met her. He hurried to the street, excitedly imploring the coachman and the eldest, René, to walk the narrow alleys and clamber down the bank again to check beneath the old stone bridge. Her ravaged look; a sickly visage with vertigo, dragging tattered hem on cobblestone, surely would be noticed in this busy district in the bright light of day. But nothing unusual was seen. On horseback, in a panic, Leopold rode up and down the riverbank, searching in vain for her ‘til nightfall. At dawn the gendarmes, barge pilots, and farm hands began the search again to no avail, for any sign of Regina. A distressed fortnight passed. A few kilometers downstream from Lessines, lying on the grass, two lovers laughed 3 in seclusion beside the river; sheltered by a tall willow, its branches weeping precariously, down. As dappled sunlight glinted through the leaves, squinting, they thought they spied an elbow, then a breast, a buttock, a knee, appear then reappear below the shimmering water’s surface. Shielding their eyes from glare, peering down, in horror they could see a bare torso spinning slowly, tumbling immersed under the rippled surface of the sheltered cove. Her hem had snagged on a sunken branch of a fallen birch. Gently, the slow current undressed her; raising her billowed skirt up above her shoulders. Then, the caught white cloth was wound into a turban, twisted taut about her face and head. Who knows who unlocked Madame Magritte’s door? From a small gabled window of a slanted attic room the blank stares of six mannequins wearing rough-stitched unfinished hats, belie that they bore witness as their mad creator willed her scrawny frame across the cobbled street, pulled herself up, and rolled herself off the stone bridge wall, falling at last, with a dull splash. Her misery - fini, drowned in the River Sambre. Mark Goldstein *Mad hatter disease, or mad hatter syndrome, was an occupational disease among hatmakers, caused by chronic mercury poisoning. It affected those whose felting work involved prolonged exposure to mercury vapor. Wikipedia: Erethism mercurialis A Bronx Baby Boomer who began writing in 12th grade, Mark Goldstein graduated from the State U. of NY with a degree in English (class of '72!). He participated in poetry workshops at The New School and The 92nd St. Y. Marriage, kids, gettin' 'n spendin' etc interrupted the Muse until downsized/retirement in 2016. Now, playing creative catch-up and spending precious time tediously seeking a venue to share some of his eclectic pieces.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|