|

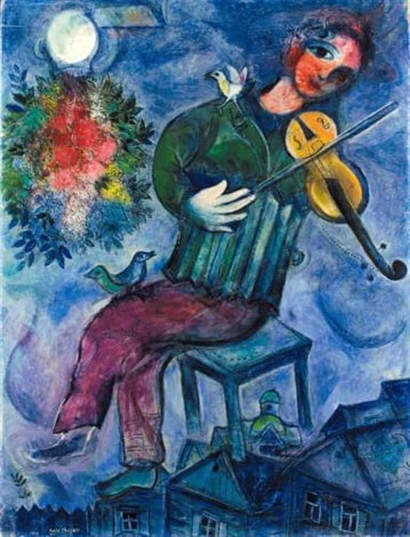

Marc Chagall’s Le Violoniste Bleu

a Personal Appreciation When I was 12 years old, my parents allowed me to travel by subway from my home in Brooklyn to “the city,” by myself. My sister, four years older than I, delighted in telling me what to do when I got there: visit Guernica at MoMa; see The Four Hunded Blows; hang out in Washington Square Park. My father read poetry to me (“That’s my last duchess painted on the wall”), recommended books (Jude the Obscure, the Jalna series) and taught me how to read and fold The New York Times. In brief, we revered the arts, and Marc Chagall, with his floating figures and Jewish themes, was a family favourite. Fast-forward 30 years. My sister and I have long periods of non-communication, followed by short bursts of intense rapprochement. During one such time, my father long dead and my mother in intensive care, I invite my sister, who currently lives in Colorado, to stay with me in my Manhattan apartment for two weeks so she can visit our mother. She stays for two months. I come home on the day she leaves to find a thank you gift: a lavishly framed, beautiful reproduction of Chagall’s Le Violoniste Bleu hanging on my living room wall. It has accompanied me from the Village to the Upper West Side to the suburbs of New Jersey. It hangs on my wall today. Chagall painted Le Violiniste Bleu in New York, in 1947, the year before he returned to France. The composition includes one of Chagall’s most famous symbols: a fiddler on the roof. He sits on a three-legged stool balanced high above a few flimsy houses and what appears to be a more substantial, official building. All are crammed into the right-hand corner of the painting. They are dark blue. On the fiddler’s left knee are two small birds facing in opposite directions. Both are blue, although the one in the foreground is darker than the other. Both seem to be chirping. A bright white moon is gleaming in a corner of the painting, and on the fiddler’s shoulder, another bird, this one white, is staring at the moon; like the other birds, he too is singing. And what of the violinist? His violin rests on his shoulder, but his chin doesn’t touch it and while there may have been a hand holding it, it looks as though Chagall painted it out, leaving only a swirl of blue. The bow rests in the violinist’s second and third fingers of his right hand, a hand that is open, white as the moon and fluid as the birds. His feet are blue but his face is tan-orange, glowing with youth and good health and is surrounded by curly black tendrils. The fiddler of Le Violiniste Bleu departs from his Chagallian brethren in some important ways. For one, Chagall chose to call him a violinist, not a fiddler at all. A violinist is a person who has trained to play the violin, who is serious and purposeful, and who is professional. In general, Chagall’s fiddlers tend to be old orthodox Jews watching over their landsmen through good and bad times, commenting with their fiddles on the births, marriages and deaths. But not this one. No, my violinist is young, fresh, doe-eyed. His look is fixed not on the shtetl, but dreamily toward the moon. My grandfather was 18 years old when he fled Russia to escape the Russian army. He never saw his parents or relatives again. He met his wife, also Russian-born, in New York. Their eldest child was my father. He was first-generation American, and, like Chagall’s violinist, he straddled two worlds. His first language was Yiddish, his second Hebrew, his third English. His parents sent him to public school, so he could be a “real” American, but he studied Torah every day at the Hebrew school. He was a Jewish mother’s dream: academically gifted, good to his younger sisters, well-versed in Judaism, respectful and loving toward his parents, and a member of Brooklyn College’s first graduating class. He was his family’s personal Pathway to America. When I look at Chagall’s violinist, I see my father. Le Violoniste Bleu is surrounded by singing birds and blooming flowers – symbols of hope and new beginnings. He is youth itself and his soulful eyes and crisp curls tell me he is a Jewish boy. The buildings have pointed roofs, but as we move up, the strokes are rounded, and the feeling is ethereal. Chagall has given us a young, hopeful dreamer who never abandons his roots; he has sent a message to the displaced, homeless ones to join him in America where anything is possible. It’s a message that resonates with me. After all, it’s my family’s history. My grandparents lived to see their grandchildren go to college and become professionals, while incorporating Jewish values and traditions into their very modern lives. Even more specifically, it reminds me that my sister and I, no matter our estrangements, both dance to the music of the same fiddler. By 1947, when Chagall painted Le Violoniste Bleu, the liberation of the Nazi concentration camp survivors was widely documented through newsreels and photographs and people were beginning to realize that in addition to destroying millions of Jews, an entire way of life – shtetl life – was gone. By emphasizing the colour blue, perhaps Chagall was also pledging loyalty and remembrance to the traditions of his own youth, while this violinist represents a rebirth of Jewish life rising from the ashes of Europe. In the early 1950s my Brooklyn neighbourhood was mainly Jewish. It was not uncommon in those days to see people with numbers tattooed on their arms: the tailor, the lady at the bank, the cashier at the grocery store. There were two rules we children had to observe: don’t stare and don’t ask. There were remnants of life before the Nazis as well. The knife-sharpener’s truck came by once a month ringing its bell and the housewives rushed from the buildings with scissors, knives and other implements that needed sharpening. The old clothes man would walk down the street, always with a huge bundle on his back, crying “Old clothes. Old clothes.” I never knew what he did with them, but my mother always saved some items to give to him. And there was the fiddler. He would appear in the courtyard of my six-story building and play a haunting melody. He never said a word and certainly never asked for a thing. Yet there was a protocol observed by all the women at home during the day with young children as my mother was. She would take some pennies from our penny jar and before throwing them down to the fiddler, she and I would wrap each penny individually in a little piece of newspaper. Then she would allow me to throw the pennies down to the old man below. Pennies rained from many windows, all of them wrapped. I asked her once why we had to wrap the pennies and she explained that it would be disrespectful to simply throw coins out the window. “After all,” she said, “he’s an artist, not a beggar. He’s a violinist!” I wonder about that old man. Is this how Chagall’s fiddlers ended their lives? Knocked off their chairs, their villages gone, wandering from one courtyard to the next, but still reminding us of the important moments in life, of who we are, and where we came from? Maybe. But not Le Violoniste Bleu. He will rise higher and higher. He will go on to do wonderful things and be an extraordinary man. Just like my father. Diana Leo Diana Leo was born and raised in Brooklyn. She spent her professional life raising money for non profit organizations. Now that she is semi-retired and the youngest of her three children is off to college, she is devoting more time to writing. She and her sister have just completed the first draft of a mystery novel featuring a large, Jewish New York family.

1 Comment

Wendy Cotter

10/13/2020 09:44:49 pm

Ms. Leo .. Thank you so very much for this important sharing. All that you feel and see in the painting is also how I feel it, and see it. .. I is difficult to find a commentary on this wonderful painting. I am going to copy yours, and have it in an envelope behind my painting to share with any of my guests who so often admire its great and moving beauty!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|