|

Minyan, or How to Wear a Prayer Shawl 1. Like a dead man. In the cemetery, kissed by Seattle rain, my friend’s father lies on a plank next to his open grave. He is shrouded in white linen and wrapped in the black-striped tallit he prayed in all his life, his inescapably human form announcing itself in the curvings of the cloth—rounding over his head and shoulders, flattening and narrowing down his torso and legs, rising again at his feet. The dead body of a human being, fitted with a new skin, clothed in a travelling garment. This is how a Jew prays. 2. Like Chagall’s praying Jew. In Aramaic, tallit means cloak or sheet, a covering. It’s the word the rabbis of the Talmud chose for the prayer shawl worn to fulfill the commandment of tying fringes, tzitzit, to the four corners of one’s garment, as a constant reminder of the Presence. I was nineteen when I first saw a Jew praying in a tallit. I was in Paris, at a Chagall exhibition at the Grand Palais. In a room alive with colour and crowded with luminous angels, dancing fiddlers, floating brides, and grooms carrying bouquets, a lone man in black and white stunned me. A bearded Jew engulfed in a tallit--the tallit worn by Chagall’s father, the catalogue said, worn by a wandering beggar Chagall invited in off the street. The man’s face, a face of sorrow, emerged from the opening of the tallit like a child being born from a womb of light into the darkness of the world. One long edge of his tallit was jagged, the black background devouring his white shelter, enemy incursions into territory set aside for peace. The black stripes too were advancing. They were escaping their woven edges, pushing beyond the boundaries set by the light, threatening to undo creation, threatening chaos, violence, death. Yet the man was not shaken—his body as still and solid as the squared phylacteries on his forehead and arm, his gaze fixed beyond. Trusting in his refuge of wool and its blessing: “How precious is Your kindness, O God! The children of the earth take refuge in the shadow of Your wings…For with You is the source of life; in Your light we see light.” (Psalms 36:8, 11) Echoing the prayer of the artist, that he, as he said, might express in his work “my sigh, the sigh of prayer and of sadness, the prayer of salvation, of rebirth.” This is how a Jew prays. 3. Like a child afraid of the dark. In my early thirties, while still a Presbyterian teaching in a Christian seminary and guest-preaching in churches, I had recurring visions of being buried in a tallit. I flew to New York. In a Jewish shop on the lower east side, the clerk followed me around. “For your husband? Your son?” he asked as I headed for the large wool tallits hanging near the back. “For me,” I said. He stopped. “Look over here,” he said, walking to a rack of narrow rayon tallits. He draped one with soft blue stripes and silver metallic stitching over his arm. It was only 12 inches wide and the first three words of the blessing, Baruch Attah Adonai, were stitched near the neck. “Try it,” he urged. It was slippery and hung weightless around my neck, more like a scarf a woman might accessorize her outfit with or the courtesy tallits provided for guests in non-Orthodox synagogues. I handed it back to him. “I want wool,” I said, “white with black stripes, no decoration, large.” He returned with a traditional 64” X 76” Turkish wool tallit. It fell heavily on my head and across my shoulders, cascaded to my feet. I bent down to grasp the tzitzit, which were brushing the floor, and gathered the shawl around me like Chagall’s praying Jew. My dream tallit. “Let me get you another size,” the clerk said. “You don’t want it to drag on the ground.” “No,” I said, feeling its warmth. “This is the one.” At home, each night before going to sleep, I spread my tallit over my blanket and slept under it, reciting the words of the evening prayer, “Spread over us the shelter of Thy peace.” This is how a Jew in the making prays. 4. Like a man. When I became a Jew four years later, I began wearing my tallit in public, in Shabbat morning services. In my congregation many women, adopting the tradition once reserved for men, wear a tallit. Many of them choose not to pray in a traditional tallit but in a tallit fashioned for their bodies and lives--properly sized; made of pure silk, raw silk, dupioni silks, voile, and organza; hand-woven, hand-painted, hand-embroidered, and hand-appliqued; in pink, coral, peach, purple, teal, and gold; adorned with doves, flowers, pomegranates, stars, flames, and tree of life. They wear them around their shoulders like shawls. Not like the men, who, after draping their tallit over both shoulders, fold up one long side over one shoulder, then the other, a tidy sartorial solution for an ungainly garment. My tallit is a traditional tallit, unmistakably created for a man, and I, ardent feminist, lover of beauty, champion of art and the hand-made life, wear it like a man. This is how a Jew prays. 5. Like a woman. At home I do not decorously fold my tallit over each shoulder to pray, as I do in synagogue. When I pray alone, I unfurl it, kiss the collar as I recite the blessing, then whirl the wool over my head and around my body and let it fall around me like a shawl. I gather the tzitzit of the four corners in my hands, hold them over my heart, and sway, like a mother soothing her baby. The black stripes near the fringed ends meet down my front. Seven rivers of ink flowing across fertile blankness. Seven rivers of letters, out of which the words of my life, the word of my life, my past, my present, my unknown, has been written, is being written, will be written. Seven lines of text waiting to be read. Our lives, too, are texts, say the mystics. It is not enough to expound the words of Torah, says Rabbi Leib, one of the Hasids of the Baal Shem Tov’s circle. We must become entirely a Torah, in our habits and our motions and our motionless clinging to the One. Standing tall, wrapped in my tallit, I become a living text waiting for its meaning. This is how a Jew prays. 6. Like a desert dweller. Desert peoples, men and women, wear an all-purpose outer garment—an abbaya or aba or keffiyah—that is kin to the four-cornered garment the Torah commands the Hebrews wandering in the wilderness to tie tzitzit to, the four fringes that remind one of the surrounding Presence that accompanies one everywhere, fringes of remembrance. One garment—a cloak to shield one from the blazing sun by day and the bitter cold by night, a covering that is armor against sandstorms, a bedsheet, a blanket for the fevered, a carrying sack, a guardian of one’s modesty, a baby carrier, a wedding canopy, a winding cloth. Shelter, protection, remedy, blessing. Garment of survival, garment of life. Garment of remembrance, garment of death. This is how a Jew prays. 7. Like Jesus on the cross. At the Chagall exhibition in Paris, after my encounter with the praying Jew, a second painting held me captive: White Crucifixion. A dark scene in blinding white, with Jesus at the centre. Not the Jesus I knew, bloodied saviour of the Gentiles, wrapped in a loincloth and flanked by two criminals being crucified with him. But Jesus a Jew, hanging on a crossroads of light, wearing a tallit and surrounded by Jews. In the heavens, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob grieving over him, and Rachel weeping for her children. And on earth, Jews fleeing the Nazi extermination, carrying food, babies, menorahs, a Torah scroll, prayers, fear. His suffering their suffering. Their suffering his. The body exposed, the spirit at risk. His tallit covering his intimacy, his humanity, his dignity, his awful vulnerability. Theirs. The black and white stripes like waves of sorrow, the fringe like tears. His tallit a shield of light against the darkness, spreading light to the cross and the four corners of the world. This is how a Jew prays. 8. Like a faqir drunk on the Beloved, a wandering dervish who secludes herself in a cave to be alone with the One she loves, to remember, to be reborn. Sometimes at home, in the hours before dawn, when darkness lingers, hanging heavy on my soul, I kiss my tallit, swirl it over my head, saying, “My soul, bless the One! Wellspring of Life, Fountain of Light, Dwelling of the World, You have garbed Yourself with majesty and splendor. You wrap Yourself with light as with a garment; You spread the heavens as a curtain” (Psalms 104:1- 2), then let it fall over me. I gather the tzitzit together and sit cross-legged on the ground, the four corners meeting in my lap. Enclosed in my cave, my womb of light, I sigh like Chagall, a sigh of prayer and sadness, the prayer of salvation, the cry of rebirth. The silence strips me bare. Tears fall. Anger flares. Joy rises. Whatever has been hiding. The wool traps my body’s heat, warming me and giving off a sweet animal smell that comforts and arouses me. It lies heavy on my hair, my head, my shoulders, arms, back, legs, spirit—a steadying embrace. Golden light seeps through the woven threads. I close my eyes and the cave expands to the ends of the earth and beyond, into nothingness. I am a speck of the universe, but a speck held by love. My fingers find one of the tzitzit to trace the name of God written there, the tetragrammaton, Y, H, W, H, the four letters spelled out by eight threads knotted ten times with thirty-nine wraps of the longest thread to set the name in motion, send it flying beyond the limits of language. The name of the Unamable. The knotted name of God. The knotty name of God. The fringe of the Unknowable. My fingers rub over each knot, each wrap, following the threads, touching the hem of what is holy. This is how a Jew prays. With her hands. With her body. With her wild spirit. 9. Like a dead woman. Like a whirling dervish, one of Rumi’s dancers. At home, alone, when I stand to pray with my tallit over my head and sway and sway under the weighty wool, arms outstretched, fringes flapping, I dance with the poet and his Mevlevis, who whirl and whirl, like the planets, like the cosmos itself, under their tombstone-shaped hats, their white shroud-skirts spinning wide. A dance to slay the ego, to “die before you die.” A dance to be reborn in truth. And when my dancing days are over, when my breath ceases, my body will lie on a plank next to my open grave, alone, shrouded in white linen and wrapped in my black-striped tallit, my new skin, my travelling cloak. This is how a Jew prays. 10. Like a newborn. Swaddled. Wrapped tight. Head to toe. As if back in the warmth of the womb, once again one with the mother. Womb of mercy. Womb of love. Womb of light. This is how a Jew prays. Mary Lane Potter Mary Lane Potter is the author of the novel A Woman of Salt and Strangers and Sojourners: Stories from the Lowcountry (both Counterpoint Press). Her essays and stories have appeared in Parabola, Witness, River Teeth, Still Point Arts Quarterly, Rogue Agent, Minerva Rising, Feminist Studies in Religion, SIGNS: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Women Studies Quarterly, Beloit Fiction Journal, North American Review, Tampa Review, Tiferet, SUFI Journal, Spiritus, Leaping Clear, and others. She’s been awarded writing residencies at MacDowell, Hedgebrook, and Caldera, as well as a Washington State Arts Commission/Artist Trust Fellowship. http://members.authorsguild.net/marylapotter/.

1 Comment

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

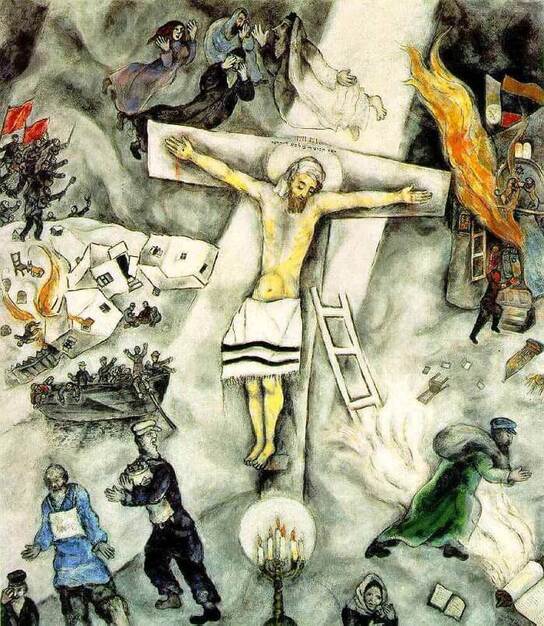

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|