|

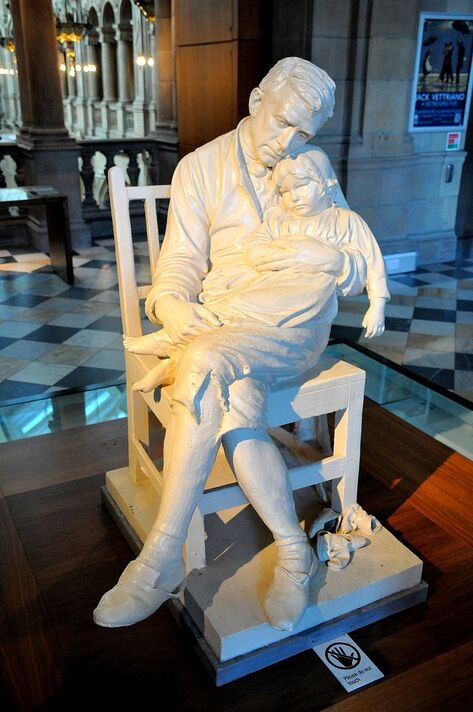

Motherless It is a little past nine. A cold wind in the dark street. I ring the doorbell. The hall is lit by a lamp only, as it always is. I ring again, and again. The quick-ring method usually draws her attention from whatever film or magazine it is today. Last time I visited she had to shout over the blaring Motown classics CD I’d bought her for Christmas. I go round the side to look in the kitchen window. Some white plates catch the moonlight in the drying rack. The kitchen tap hangs a water-bead stalactite. Before leaving I decide to look again through the small pane on the front door into the hall. The phone is blinking with the number of messages waiting – three – beside the hairbrush on the table. Above the table a calendar says Bless This House. A blue-eyed angel with a trumpet declares this blessing from a cloud. Beside the calendar is a large mirror, bending light up the staircase. I half-expect to see her coming down, her hair up in the old style, vintage house-coat, slippers and all, emerging from a different era. Back in the car I spent another hour trying to reach her mobile. Half-way home I pulled over as she phoned me back. She’d been round at one of the neighbour’s houses. An old man. His cat had died. They were all there, the other neighbours, consoling him. It was the only thing he had left, she told me, "the only thing in the world." It seemed like a good time to mention my father. Driving home, I couldn’t settle on a radio station. I kept thinking about her tap not dripping and the sound of her voice, cold and crackly over the phone. In my father’s last days there was a swell of something in his eyes that wouldn’t give way. A fullness that must have been too much to bear. I pictured the old man whose cat had died. The neighbours all around him, patting his back and offering nonsense platitudes. I pictured him sitting there silently, not listening, nodding. The next day I finished work early and walked down the Kelvin Way Bridge. Flanking either side were statues of people from another time. They weren’t real people, they stood for things like Industry and Commerce. Peace was a woman with a spinning wheel looking down at her infant child. War, of course, was a man; grasping weapons in one hand and tucking a helmet with the other. Shirtless with a bandage round his head he was shouting some command or simply shouting in pain. The eastern-looking domes of the Kelvignrove Art Gallery and Museum rose from the tree-line to the west. As I entered the main hallway the last blasts of the organ cascaded off the grand walls and tiled floors. A scattered applause reached up to the old organist, who in turn gave a comedic bow to the dwindling crowd. I went wandering, passing the cracked pots and polished coins from Egypt. Upstairs I breezed through the Scottish art, stopping now and again to meet the gaze of the kilted gentry and wild stag. On my way back down to get a coffee I found myself in the middle of some sculptures. People, mostly women, leaning wistfully here and armlessly there in the all-white shroud of Plaster of Paris. A young boy of about ten years old pointed to an exposed breast and laughed, and I wondered if his was the age when the connection to their mother’s nurturing body is rewired for jokes and sexual fantasy. I stopped at the last one in the row and took in the details. A man seated on simple chair with his legs crossed. His trousers were unbuttoned below the knee, giving way to the smooth likeness of ribbed hose. I presumed he was a Victorian. His shoes were as comfortable as sculpture could suggest, but it might have been the playful dangle of his foot that gave the impression of comfort. If only it were possible to take in those features in isolation. You might then take him for a man of leisure – perhaps settling down to read a book or take part in some light conversation. But his face, and the infant child in his arms, told a different story. With his left arm around the body and his right hand cupping a leg, he pressed the little girl against him, nestling her into his neck scarf. His face leaned down towards her head, connecting permanently with her hair. Little ringlets behind her ears curled onto her shoulder and one of her arms hung down to the floor. My eye traced a line down to her little empty hand. A break in the unity of their embrace. Their faces matched with expressions as blank as their clothes, as fixed as the chair they perched on, which was fixed to a concrete base, on yet another plinth with the word etched in, Motherless. Downstairs I watched the steam float on the surface of my coffee. Thinking more about the man and girl I realised this was my first experience in one of these galleries where I didn’t have to feign interest. The details kept setting down like dust. The cut of the man’s eyes: deeper than the girl’s as though suggesting his deeper sense of loss. The girl’s feet, I remembered, were bare. I had neglected to check the name of the sculptor, but I was sure there had to be something driving the subject: some level of experience. I wondered if maybe the artist had seen this man one day, or if it was a self-portrait. I found myself hoping it wasn’t the latter. Whether imagined or lived, this moment of loss survived. Two sets of eyes looking into an empty space for something missing, not seeing the people drifting by and growing (mercifully) old. My coffee was still too hot. When I got home I tried to explain to Charlotte what I’d seen but in hearing the words in my head before saying them I felt myself shrink. Instead of describing the sculpture I mentioned this painting of an old Scottish codger with a hard stare. "The famous one," I said. "Was it the Macnab?" she said. "I can’t remember. I think he had a dog." "That’s not the Macnab then." We ate dinner and unfolded on the couch for an hour or so. There was no expectation in the air. When we went to bed a little earlier than usual she was warm, loving. She kissed me on my lips, on my nose, and my forehead: tracing a line up my face from passion to comfort. I closed my eyes and felt her hand on my forehead, as if checking for a fever. In bed I listened to her pages turn a while before the light went out. As my eyes adjusted to the dark room my mind wandered back to the museum. A black tile here, a white one there. Soon the tiles filled my mind and I crawled a purgatory’s length to the sculpture, now the only piece on show and the size of a mountain. I began the climb up from the base to the leg of the chair to the man’s suspended foot, and from there up the leg towards his megalithic fingers. Looking up to the cavernous eyes I felt a flutter of vertigo. I opened my mouth to speak but instead I focus on Charlotte’s deep breathing. In the morning she would forgive me for being cowardly with my mother. She was never one for vocalising anyone’s faults but her own. Sometimes, as I walk past her in the hall or watch her read, I imagine that her soul is growing deeper, stretching out to accommodate a heavy sadness. A burden that only a void can create. A void that has a shape, though I am too afraid to name it. Craig Lamont Craig Lamont is an academic and writer working at the University of Glasgow, carrying out research for the new scholarly editions of the Works of Robert Burns (Oxford) and the Works of Allan Ramsay (Edinburgh). Besides Scottish Literature, Craig's research specialism is cultural memory. His monograph, The Cultural Memory of Georgian Glasgow will be published early 2021. Before working in the eighteenth century Craig completed a Masters in Creative Writing (University of Strathclyde) and worked at an independent publishing house, Cargo. Craig writes short stories mostly, some of them published in Scottish journals and magazines over the past ten years.

1 Comment

Ms Jean Strachan Smith

4/30/2020 04:43:48 am

Enjoyed. The short story

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|