|

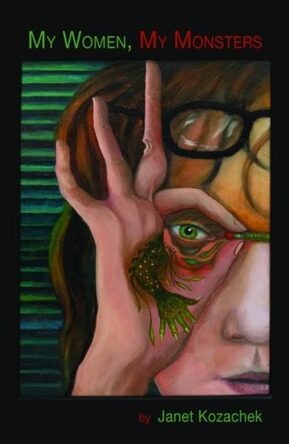

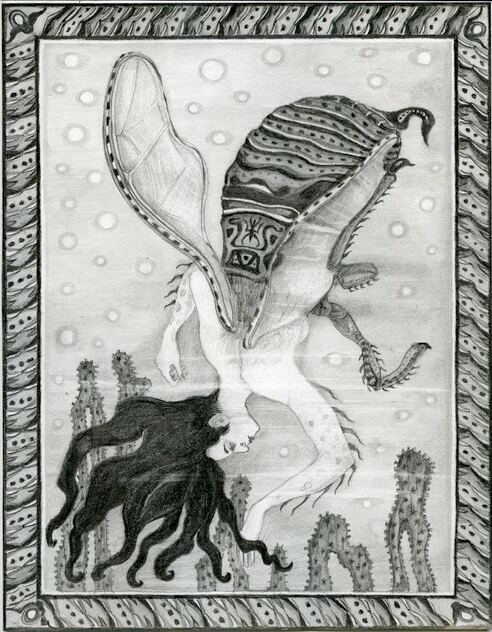

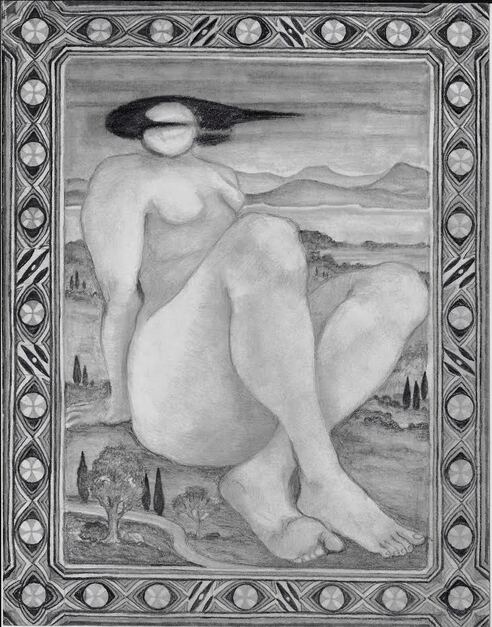

My Women, My Monsters: Dr. Sarah Wyman Interviews Janet Kozachek About Her New Book (SW) What inspired you to write and illustrate My Women, My Monsters? (JK) Initially, a social media query that was posted nearly ten years ago from a musician I became acquainted with in the summer arts program, Common Ground on the Hill, at McDaniel College in Westminster, MD. He had hosted an online roundtable discussion on gender issues. One of the questions he posited was why there were no depictions of women monsters in American culture. (SW) What was your reply? (JK) I mentioned several instances of powerful women monsters such as the Indian Kali, the Chinese White Bone Demon, and the Russian Baba Yaga. From the ancient world, I brought up Greek Harpies and the Gorgon. (SW) And none of those are North American. (JK) Exactly. They are all notably Eastern, Eastern European, or ancient Mediterranean. (SW) So how do you account for the relative absence of such archetypes in U.S. culture? (JK) It could simply be that the America of European transplants does not have a unified, consolidated, ancient culture and therefore lacks the foundation for the development of a mythology. It could also be a peculiarly American anathema for, and a fear of, feminine power. (SW) With My Women, My Monsters, you seem to create a novel set of creatures from old stories and new imaginings like Mary Shelley with her nineteenth century iconic Frankenstein. (JK) I did quip back then, when this discussion originally took place, that I would have to address the meagre supply of American female monsters by inventing some, but I am not certain that I succeeded, as so many of the monsters in my book still alluded to myth of other cultures and ancient myths. (SW) Could some of them be a part of a uniquely U.S. mythology that has its roots in histories around the world? (JK) For most of the monsters in the book, I ended up relying on ancient Greece and Middle Eastern figures, one proto-Elamite figure, and others that have Eastern or Eastern European roots. But some of the monsters in the book were the result of myth making from personal experiences and interactions. I suppose one could say that these are American in the sense that they spring from the imagination of an American Artist. (SW) Some of these monsters are quite frightening. To me, the scariest is the small Succubus bed bug who takes you to places where “traffic transports you to accidents.” I won’t ask you to verbally define the fear that you capture so well with the visual, but maybe you could speak about the way you zero in on details from the larger images as though focusing the lens. (JK) The most monstrous things in nature usually are small, even microscopic. Succubus taps into that natural physical aversion we have to parasites or unseen microbes. Before I committed to studying art, I was a science student - pre-med, in fact. It was oddly humbling to witness the mechanisms by which human beings, despite our best intentions, our dedication to our education, our careers, and our families, can be brought down by something so simple as a virus. It seems so random, so banal. In most of the illustrations, in a style reminiscent of illuminated manuscripts, I do pluck out a thematic form from the central illustration and make a repeated pattern of it in a border design around the image. Sometimes this is purely decorative, usually it isn’t. I have an illustration I made, for instance, called “Phrenological Overlay,” which is a satire on certain aspects of nineteenth century ideologies that remain as hidden artifacts in modern medicine. The border is decorative and attractive, but an intrepid observer will notice that the design is constructed from flies set end to end with a maggot in the middle. It is still pretty, though. (SW) Some of these so-called monsters are quite amiable or admirable, such as the Titan who seems a powerful, inviting Mother Earth figure, the meditative, metallic, Mummified, or the Crow with her paradoxical “benevolent predations.” In the introduction, you claim, “it is fundamentally human to keep love and hate on the same page.” Are you ambivalent in your feelings about some of these beings? (JK) It was important for me to keep all of the “monsters” in this book physically beautiful in varying degrees, regardless of whether they inspired admiration or horror. I am not ambivalent about their impeccable style. (I also enjoyed the oxymoron of “benevolent predation.”) I am sometimes satirizing, in these examples in particular, instances in which goddess-like figures can be called “monsters” due to mistaken identities. The Titan comes from a large drawing I made many years ago at an art institute in Holland, where a male art professor found her terrifying. Crow, if you look closely, wears a brassiere through which nipples are visible. According to rules set by Facebook, I cannot use this in an ad because this violates their standards of community decency (in fact, most of the illustrations do). There is often a thin line between monster and goddess depending upon who is doing the looking and naming. SW) You mention Common Ground on the Hill as an original inspiration for your poetry and illustrations. How did that experience shape your creative process? (JK) While at CGOTH, I studied spoken word poetry with Lee Francis and song lyrics with Bob Lucas and Lea Gilmore. This proved to be very useful in honing the rhythm and meter of my poetry. You never truly know how a poem sounds until it is out of your head and trips off your tongue. Even writing it down is not sufficient to know whether or not it keeps the right beat and holds together as a verse. (SW) Were there any other experiences with poetry and writers’ groups that you feel helped shape your poetry? (JK) We had a local group in Orangeburg many years ago. I had met poets, writers and scholars back then whom I continue to keep up with today. A second incarnation of the Orangeburg Writers Group helped directly shape some of the poems of My Women, My Monsters. One young member, for instance, related a dream she had of a race of giant cyclops residing in Sub-Saharan Africa. Her dream became “The Wife of Polyphemus.” (SW) Have you met up with some monsters? (JK) Of course! A few...women with repressed rage, women who might desire to spoil the joy of others, duplicitous women who would take advantage of others. They shape the part of the book that has a psycho-social dimension. These are what I think of as archetypes that manifest the demands that women are subject to, and what they subject themselves and others to. (SW) Your book ends with the line, “I see my monsters. I know myself.” This would seem to indicate some monstrous introspection. (JK) That last line of the last poem echoes the last line of the first, in euroboric style (the snake grasps its tail and makes a circle). Apart from being a structural effect, the line points to an internalization of history and experience, ending in somewhat of a mea culpa. As an inveterate list maker, for instance, the wickedly compulsive “Duchess of Lists,” comes to mind. (SW) We’ve spoken about the text, but what makes your book unusual is that it is composed of drawings as well as poetry, in an ekphrastic relationship. Can you tell us something about how you came up with these images and how word and image play upon each other in your work? (JK) Technically they are related to a style of ink painting, called gong bi, that I learned many years ago as a graduate student at the Central Academy of Fine Art in Beijing. This style incorporates crisply delineated calligraphic lines enriched with tonal gradations of ink. It occurred to me that I might be able to reproduce that effect in pencil using extra soft and dark 9B then gradually overlaying these dark lines and velvety black spaces with lighter, harder pencils and grading the tonality smooth with stumps. (SW) What about the images themselves? (JK) These come from a variety of sources - the Lioness is adapted from the proto-Elamite stone carving I mentioned earlier. I made a sketch of this lion-headed figure while she was still available for public view. Others were gleaned from life figurative studies. The rest were from a combination of memory, imagination and studies from nature. (SW) You have a long history of depicting women in your paintings, drawings and mosaics. I am reminded of your beautiful double-sided mosaic masks that we have discussed in earlier interviews. Were they monsters as well? Or did they invite us to try on our own more monsterly or unconventional personas? (JK) Some of my ceramic figures were taken from Rubens’ paintings of Amazons. The mosaic masks were fun. There was one that I literally could wear and it felt transformative when I did. I still have photographs of myself dancing with one on! The double-sided masks solved a problem I had with an unfinished obverse side of the mask, so I created another world on the inside of the face. I have always been interested in dualities, in this case, the face shown to the world versus the personal interior that only we ourselves can know. (SW) What inspired you to be both writer and illustrator? What do you find compels you to create in both word and image? (JK) I have always loved the embellished word - illuminated manuscripts, exotic scripts. While in China, I learned the art of calligraphy and poetry composition. A Chinese painting is not complete without them, as well as the addition of the printed word in the form of stone seal imprints. The print, the writing, the image, all form the integral parts of a whole aesthetic experience. Having been inculcated into this multivalent way of understanding art, I subsequently found my experience in an American graduate school in painting to be missing an essential part. Painting and drawing without words felt lonely. Fortunately, while at Parsons School of Design, I studied with poet, author, and editor of the Yale Review, J.D. McClatchy. McClatchy had just recently authored Poets on Painters, and I felt a kindred spirit with someone who understood the possibilities of a concomitant expression of word and image. (SW) Some would find it unusual for a woman to create a book that, despite its celebration of strength, whimsy and ingenuity, appears to excoriate other women. Are you anti-feminist? (JK) I support equal rights for women, with equal pay for equal work and complete autonomy in women’s choices with respect to their health, welfare, and bodily integrity. I especially wish to see equal representation in government, education, science, and healthcare. It is important to understand, however, that sexism, like racism, is an evil institution. Do I think that this will disappear with more women in positions of authority? Not necessarily. There is no guarantee of that. As the meta-ethicist Professor Kate Manne discusses, a woman in a position of authority may have a greater allegiance to men and women who wish to perpetuate a system that is unjust and unfair to other women - especially to poor women and to women of color. The existence of feminist men and sexist women is possible and real. Our humanity or monstrosity lies in our choices to uphold or abrogate our commitment to equanimity and justice, regardless of gender. (SW) Perhaps your gender-bending Guenell lioness with her “haunches of a feline/tightened by the sight of prey” plays with these possibilities of life beyond the binary? (JK) The historical Guenall Lioness is a privately, anonymously, owned stone statue that had previously been on long-term loan to the Brooklyn Museum. One could make some interesting observations about shifts in cultural attitudes towards gender ambiguities by reading the various descriptions of the statue in art history texts from different eras. Early writings refer to her as “The Guenall Monster.” In later writing, she was “The Guenall Lioness.” In the last catalogue in which she appears, published by Princeton University Press in 1997, she becomes androgynous again in her new title, “Leonine Figure.” Clearly, a statue with a woman’s pelvis but a man’s well muscled upper torso appeared monstrous to some, was embraced and appropriated by others, and finally had her identity deftly skirted in a noncommital way that bordered on the puritanical. My poem addresses those shifting perspectives - the monstrous or the goddess-like is in the eye of the beholder. The original statue, by the way, lacks lower legs and feet. In my illustration I have added those. I hope that this is not looked upon as too philistine. In short though, yes, that 5,000-year-old Lioness, who marches boldly forward as man and woman in one, timelessly reminds us of our unity. (SW) Thank you for speaking with me and for your beautiful work. (JK) My pleasure. My Women, My Monsters: Written and Illustrated by Janet Kozachek Interview with Dr. Sarah Wyman, SUNY New Paltz

1 Comment

Tamara Miles

12/11/2019 06:16:47 pm

Janet is such an incredible person and artist. My friend, too... how lucky am I. Thanks for a great interview. I enjoyed reading about the work.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|