|

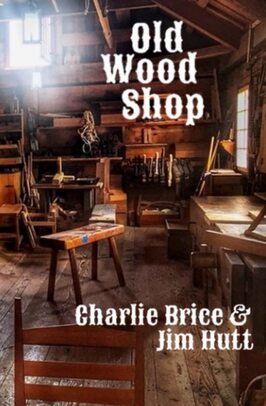

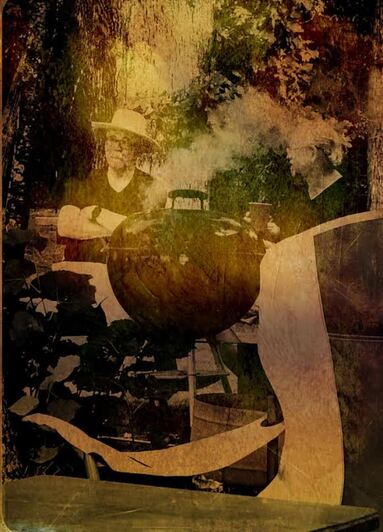

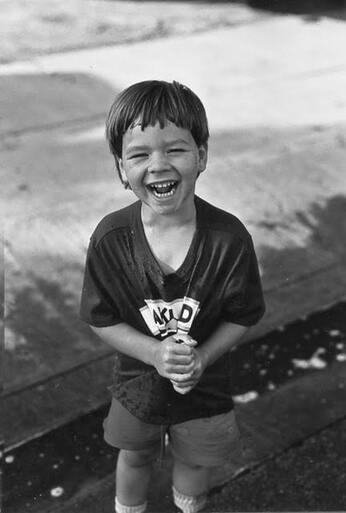

Old Wood Shop (Impspired Books, 2021), by Charlie Brice and Jim Hutt In Charlie Brice’s words and in Jim Hutt’s images there grows a palpable nostalgia from under the bones of vehicles and barns and ships sleeping in fields. Each photograph and word is deliberate in its reflection both inward and outward, both backward and forward in time, to end in a path which regenerates in each friendship, each young laugh. This collection masterfully conveys a feeling that our places, our bodies, will be abandoned one day but will still be perpetually vibrant in the threads of memory, in the words of our children, in the pictures we have kept under our lost skins. From the first poem, “Woman at Window,” we see Brices’s ability to take an image of an immediate moment and stretch it out through time and space: “The same nothingness…has placed her reflection / against what grows and flows, / against what lights her way / through the dark.” And following in the next poem, this opening into eternity continues with: “panes that open, / through tears, to what grows green, / and frames what flows, to what births / flowers and floods.” Hutt’s photographs lend themselves to reflection from the minute details of an abandoned “Lund” family farmhouse captured in black and white, the image looking textured and weathered as the “rotten / floorboards and sloping eaves,” to the symmetric wooden frames of “Phelps Mill Grain Chutes” where “Deep inside one structure is another / structure and still another.” But even in the historical tableaus Brice and Hutt capture such as a club filled with wealthy white men who “cemented exclusions: blacks, browns, / yellows and women—those who had / to be Other in order to keep those men / comfortable,” Brice does not shy away from showing the injustices of the past in clarity. He also shows the invincibility of a familial bond in “Brothers:” “That brother has no / righteous blather: religion, politics, even / beloved sports teams can’t destroy the bond.” In the poem “Duet” Brice chronicles the musical relationships between another set of siblings: That final evening, they played Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata, Joseph on piano, Ben on violin. Such hardy music, full of strength, hope and strife. At the core of this collection we can see each speck of sawdust and each stain of sweat from the past so clearly, owing to the work each person has put forth to sustain a life: This is where hands counted and all that was done was done with muscle, sweat, heart, and heft. Yet even within the same poem, Brice springs us from the labors of the individual to the respiration of the trees, and, in fact the world: Everything in this room once respired, housed birds, squirrels, and forest voles, soaked up sun and conjured shade. Again, Brice takes each frozen piece of timber, each glorious picture, and makes it sing with mystery. In “Sunset on Pelican Lake,” Brice reflects on the tangerine and blood hues of the sky and the water: “but here / there is no god, not even the dream / of a god—only the silence of twilight / and the secrets of the depths.” The strength of Brice’s poetry and Hutt’s images is the emotional depth and resilient humanity they convey. The last poem / photograph pairing “The Laughing Boy,” the collection is concluded with a bright grin of hope as a child grips his shirt and opens his mouth wide in a laugh. And Brice masterfully writes: “The laughing boy inside us calendars / our best days, punctuates our dark / gestures, rescues us from despair.” We all need this type of transcendent spirit, especially in these times when our survival depends on it. Both Brice and Hutt deliver it here. Scott Ferry Scott Ferry is a poet, and author of These Hands of Myrrh (Kelsay Books). Old Wood Shop, pictured above, is a collaboration between our regular contributor, poet Charlie Brice, and his friend, photographer Jim Hutt. We talked to both of them about the project. Talking with Charlie Brice, Poet, About Old Wood Shop The Ekphrastic Review: You frequently write ekphrastic poetry about paintings. How does writing from photography contrast with that experience? Charlie Brice: That’s such a fascinating question. I have to say that there isn’t any contrast for me. To me, it’s all art. I’ve written poems to music and sculpture as well as paintings and photographs. I let the artwork inhabit me, take me places I couldn’t have gone on my own. I look at the piece and let my mind go. In ekphrastic work, I’m interested in the associative process, the flow of consciousness and unconsciousness that the piece provokes in me. I don’t care for ekphrastic work that simply describes. In my view, a poem that merely describes the work in words is redundant. Who needs a poem that literally describes a photograph or painting? Why not just look at the painting or photograph? What was it like writing poetry in response to the artwork of a friend rather than a stranger? Jim Hutt and I have known each other for fifty-five years! He is the closest thing I’ll ever have to a brother. No, he is my brother. We can often finish each other’s sentences and have, on many occasions, wound up texting each other at the exact same time, and they were crazy times, like 2PM on a Saturday afternoon (11 PM his time). We also love to razz each other and have sometimes startled others as they listen to us hurl good natured insults at one another. So writing poems to Jim’s photographs seemed as natural to me as having a conversation with him. The nature of our relationship, the love we share, made me feel like I was completing in words what Jim had begun in a visual medium. I don’t think I could have had anything like that with a stranger. What’s your favourite photograph in this collection? Tell us a bit about why it speaks to you. It’s very difficult for me to pick one photo. They are all so vital, so well crafted, but if forced, I’d say my two favourite photos are Old Wood Shop and The Laughing Boy. The artistry of the photo, Old Wood Shop, is stunning. The texture is remarkable. It’s as if you can feel every object in that room—the wooden bench, the tools, the splinters. And the light! Look at how the light blankets the table in that photo. I want to walk into that shop, into that photo and stay there. As for The Laughing Boy, if anyone can look at that photo and not feel better about themselves and life in general, then they’re dead and don’t know it. I felt that boy inside of me, that joy, that exuberance. I think we’ve all got that kind of happiness inside of us. Unfortunately, the stuff of life can sheath that ekstasis, but Jim’s photo helps to bring it out of us, if only momentarily. Was there a poem in this collection that you struggled with? Can you share the specifics, if so? What was your process like for writing these? I have never experienced a writing process like the one I engaged in on this book. There was no pressure, no time limit, but these poems just poured out of me. I wrote the twenty-two poems in the book in less than a month! And each poem went through at least three and up to ten revisions. Each one of these photos spoke to me in such a vital way. I’m sure that is because of the love Jim and I share for each other through our long friendship. Our mutual friend, Monica Beglau, suggested that I write poems to some of Jim’s photos and I/we took up her suggestion. Monica was the editor of our high school newspaper back in the antediluvian period. She was the first to publish either one of us. We agreed to do the book, but only if she would write the introduction, which she did. From Monica’s suggestion to Steve Cawte, our publisher at Impspired Books, the entire process only took three months! Steve did a tremendous job putting this book together for us. I’d written for his marvelous UK journal, Impspired Magazine, and when I asked him if he’d be interested in our book, he said definitely. I thought it would takes months to publication, but I think Steve put the book together in about three weeks! Your poetry here contemplates the sacred and mundane, and everything in between- the nuts and bolts of our very existence. Engines, gears, cigars, sunsets, peeling paint, the old wood shop. What can you share about the act of noticing, and documenting in poetry? Why do writers have this compulsion to witness, to look deeper, to contemplate? In his moving elegiac poem, “In Memory of W.B. Yeats,” W.H. Auden wrote that, “Mad Ireland hurt [Yeats] into poetry.” I think many poets write from a great place of hurt, of existential injury. I have written elsewhere that the nuns I had in grade school and high school hurt me into poetry. That’s another aspect of life that Jim and I share. We both feel that the nuns we encountered, with few but notable exceptions, were angry, sadistic, and mostly stupid tormentors who tried their best to kill our spirits. For me, having alcoholic parents, also hurt me into poetry. The point is, these existential injuries produce a hyper-awareness not only of one’s inner states, but an acute, if often weary, compulsion to observe the inner lives of others if, for no other reason, to anticipate possible attacks. Poets connect to others through their pain, but also through those bright spots in their lives. For me, humor became a way to both cope with pain and get access to it. I think Jim and I share that part of our lives as well. I don’t know anyone who is funnier than Jim Hutt. There are times we get together and make absolutely no sense, but laugh a lot. Both of you are psychologists, so I will ask both of you this question: how does your professional experience and perspective on human behavior inform your creative work? How does your life practice in psychotherapy/psychoanalysis affect the way you express yourself artistically? This is a fascinating question. I’ll be interested to see how Jim answers it. For me, as a poet, my training as a psychologist and psychoanalyst gets in the way of doing my craft. For years I actually had to practice a kind of professional forgetting in order to write good poetry. Let me explain: my former field is extremely reductionistic. A patient comes into the office with complicated symptoms, a complicated and complex life, and it’s the analyst’s job to find the themes that are running through the patient’s life and help him or her see those themes. That’s why it’s called “analysis.” It’s extremely beneficial to help a patient see that, in her relationships, she’s duplicating relationships from her past over and over again and that’s why her relationships aren’t working out. For example, the patient always seems to find partners who mistreat her because, unconsciously, she has being mistreated confused with being loved, etc... . So there’s a reduction of her relationships to a theme: being treated badly is akin to being loved. See what I mean? Once a patient becomes aware of that theme in her life, she’s in a position to change that. Doing that to a poem, reducing the subject matter to a few themes, would be akin to T.S. Elliot writing, “It’s bleak,” instead of all the five stanzas of “The Wasteland.” When I sit down to write a poem the very last thing I want to do is reduce the material to a few themes or threads. Instead, I want to describe its complexity, confusion, complications, ambiguities and paradoxes. I want to celebrate these phenomena, not reduce them. Let the analysts look at my poems and reduce them to my neurotic issues, I don’t want to do that. I recently wrote a poem in which I changed my mind as to the subject matter of the poem in the middle of the poem. Can you imagine an analyst telling a patient, “You choose partners who mimic the destructive relationship you had with your parents,” and five minutes later saying, “I don’t think you do that, maybe you just like being mistreated? Why don’t we describe, even celebrate, your mistreatment?” Anyway, I certainly love celebrating the complexity and mystery of artwork through the medium of ekphrastic poetry and I absolutely love being a part of The Ekphrastic Review, one of my very favourite online poetry venues. Thanks for taking the time to explore our contributions to Old Wood Shop. ** Talking with Jim Hutt, Photographer The Ekphrastic Review: You describe yourself as an amateur photographer. Tell us about your interest in capturing images. When and how did you start taking photos? Jim Hutt: I think of myself as a serious amateur. My study of photography showed me the stark differences between amateur and a pro status, which isn’t necessarily obvious to the ubiquitous smart phone amateur photographers. My interest in photography emerged in my adolescence. I stumbled across an old Yashica split-image focus camera (probably my father’s) at home in Cheyenne, Wyoming when I was 16. I figured out how to load it with Ektachrome slide film, took some shots, and to my delight, they turned out relatively well for a rookie. There was always a certain angst waiting for the film to return from the developer. But it was also part of the thrill. I spent time at the library reading more about photography than anything else. That probably explains why I flunked out of college my first try. Charlie will probably tell you he’s surprised I even knew where the library was! Overseas in the military in 1971 I purchased from a duty-free shop what at the time was the state-of- the-art Nikon camera. After I returned from my successful four-year military stint (successful means I came back alive), I immediately went on a photoshoot in the Snowy Range in southern Wyoming with my younger brother, Dave, who by then was a professional photographer. That shoot cemented my love affair with photography, and Dave as my mentor, teacher, and companion on several photoshoots. Truth is, Dave has probably forgotten more about photography than I will ever know. What is your process? How do you choose your subjects? What kind of digital alterations or experiments do you use? How do you know when a photo is ready to your liking? My process has morphed over the years. I alternate between digital full-frame Canon cameras and the iPhone. Because I no longer shoot with film, I don’t have or need a darkroom, although at times I wish I did. Back in the day, post processing took place in the darkroom—a wonderful place of solitude, quiet and non-sequitor thought process. Processing now occurs in the digital realm, on the computer. Both methods can be terribly time consuming, it just depends on how obsessive I want to be in my quest for a particular image outcome. I’ve been all over the map with subject choice, which is to say, I really don’t have a “voice.” I’ve noticed that professional photographers have a “voice”—when you see their work, you know it’s theirs: It’s unmistakably Adams, Westin, Avedon, Bresson, etc. When I first started taking photos, I shot anything I thought was cool. Didn’t matter what it was: landscape, a plane in the sky, a car, a weird street scene, cat or dog, you name it. Over time I realized the camera can be a powerful communication tool, used as a platform for a message. But, life intervened—Vietnam, college, grad school, marriage, kids, career, and everything else, and I never got back to acting on that realization. My current interest is working in greyscale, although you wouldn’t know that from the book. You can blame that on Charlie. I’m particularly interested in greyscale candid street photography, urban and rural. My focus going forward is on the senseless white-supremacy-fueled racial divide we continue to live with in America. I would like to produce images in a manner that document this destructive historical horror in a way hasn’t been done before. That is not to say previous brilliant documenters don’t exist—they do, Pittsburgh’s phenomenal Teenie Harris, for one. But I have some ideas of my own I want experiment with to add to that documentation. More will be revealed. As for experimenting with images--In a sense, each image is an experiment, with the exception of family photos I take for documentation purposes. Even those I will tweak to some extent—just depends on who wants to look thinner and/or younger! LOL! The images I capture with my Canon gear I process in Lightroom, then Photoshop. If I’m working in greyscale, I also might run an image through a set of digital filters in OnOne. I post-process images taken with the iPhone employing any number of seventeen different photo apps. Each app allows for several different outcomes. That’s where it gets fun. The permutations are almost endless! Canon or iPhone, the image I want usually has less to do with what the camera “sees” than the image I want seen. And that depends on what moves me, or what I think may move others. I proclaim an image is ready for my liking/posting/printing the way Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart defined pornography in 1964: “I know it when I see it.” Tell us what it was like seeing your photographs through the eyes of a poet, after reading the poems Charlie wrote. Well, you have to understand that without Charlie, this project would never have happened. Dead stop! This project was a completely new experience for me. I didn’t know what to expect. I was shocked that my images evoked the depth of emotion that Charlie’s work brought forth! I did not anticipate that. It deeply touched me in a couple of ways. For one thing, understand that Charlie has been one of the most important and influential men in my life, beginning in high school. He was the bridge to my feeling included as the new kid, the outsider. So, co-authoring a book with him was a powerful practical and metaphorical inclusion in, and deepening of, our regard, connection and love of each other. In my experience, very few men have that. I have that with Dave and Charlie, and I’m grateful beyond words. Another thing is that the book project got me to see my own images from a deeper interior place, I guess you could say multi-dimensionally, a place beyond the aesthetics of design, composition and color. Without Charlie’s poetry that simply would not have happened. That has made photography and poetry more rewarding for me. When I consider shooting an image, I now include meaning in my decision matrix before I release the shutter. What’s your favourite poem in this collection? Tell us a bit about why it speaks to you. That’s an interesting question. I vacillate between three of them: "Railroad Car," "Brothers," and "The Laughing Boy." For me, "Railroad Car" and "Brothers" connect Charlie and me in several ways. Those two poems also reflect the strong connections I have to my three brothers, particularly Dave. In fact, my brother, Dave, the professional photographer is in the Brothers photograph. "The Laughing Boy" is my son, thirty-three, now a man. I see the strong connections he has to his male friends, and that makes me happy, gives me hope. At the end of the day, those three poems give me hope that one day men will be socialized to be in touch with their feelings or emotions; that it will be acceptable for boys and men express emotions, and that the patriarchy will no longer dictate the dysfunction we all experience between men and women because of the distortion the patriarchy promotes. But, if I have to pick one poem—"Brothers." Yeah, that’s the one. Tell us what you hope to explore or achieve with your photography. What are your plans now? Photography will always be an important part of my life—fortunately, for obvious reasons it never had to be my day job! However, there is more than a little science involved in photography, a nourishing interest of mine that feeds my intellect. Going back to what I mentioned earlier—about not having a photographic voice—I would like to achieve, or discover my voice. I imagine that it would be gratifying to know that when someone sees one of my images somewhere they would know it is mine, even if it wasn’t signed. I know as an amateur that’s not likely, but hey, dreaming is good, right? Both of you are psychologists, so I will ask both of you this question: how does your professional experience and perspective on human behaviour inform your creative work? How does your life practice in psychotherapy/psychoanalysis affect the way you express yourself artistically? Actually, I think it’s the other way around. In my experience, creativity is as much at the core of my therapeutic work as empathy, compassion and pragmatism. That said, the work of therapy is a bit like working with a photographic image. Each image is its own distinct entity, just as each therapy client is a sperate, distinct person, an “n” of one, if you will. Creativity is involved with both, albeit in different ways. The worst approach for a therapist is being formulaic with a client, although that’s what we’re taught to do. It doesn’t work. The application of a formula in a subjective milieu is antithetical to creativity. Fact is, I can be simultaneously thoughtful, experimental and creative in my responses to a client, just as I can with an image. Of course, there are significant differences: I can undue a change I made to a photograph, but obviously cannot unsay what I have said to a client. I think 43 years in private practice has indirectly affected the way I express myself artistically. It certainly has taught me to reflect on my artistry, to think about it, not take it for granted. What I can tell you is that sitting with people day-in and day-out for four decades has imprinted in me that I can’t be sure of anything, and that I know very little. To wit: I revisit “old” images and change them. So much for being sure I’m “done” with them! I know my brand of artistry won’t appeal to everyone, and that’s ok. In my opinion, my artistry and creativity are precursors to mastery, and mastery is directly connected to self-concept, and how I see myself has everything to do with my emotional availability and the extent to which I wander the planet with some sense of peace and purpose. Ultimately, I like to think creativity has been at the core of my career as a therapist, and as an amateur photographer. Brothers There’s whiskey and there’s barbecue. There’s the world’s woes and worries, its weary and worn, which these brothers save and solve in the way the Weber’s smoke curls toward heaven. Anyone can pop out of the same uterus, out of the next car in the birth train, but becoming a brother is a lifetime vocation. Despite the fights, attempts to dodge, battles to outdo one another, brothers keep each other. A brother traverses the River Styx up and back again, but never forgets. He’ll dig through the rubble until he finds you. He’ll bring you home broken or whole and listen to your drunken whine at 3AM. A brother may be from a foreign womb, may reach with a black or brown hand that pulls and pushes, tells you to keep going when all you want to do is die. That brother has no righteous blather: religion, politics, even beloved sports teams can’t destroy the bond. He understands your failures and shame and celebrates your triumphs. His “we” will never reduce his brother to a “them.” His I will find his Thou in him. Charlie Brice The Laughing Boy He’s there, somewhere inside of us. Can we find him? Twist our shirts, shiver with laughter, with delight, shake with the joy of existence? He is the beginning and the end. Nothing stands between his belly-laugh and his exuberance. If we find him, we will relish absurdity, even celebrate it. That laughing boy inside us calendars our best days, punctuates our dark gestures, rescues us from despair. Framed in white and black, he is our dream of happiness, the exultation of breath! Charlie Brice Read more ekphrastic Charlie: The Lacemaker (on Vermeer) Death and the Miser (on Bosch) The Shepherdess (on Pissarro)

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|