|

On Hockney

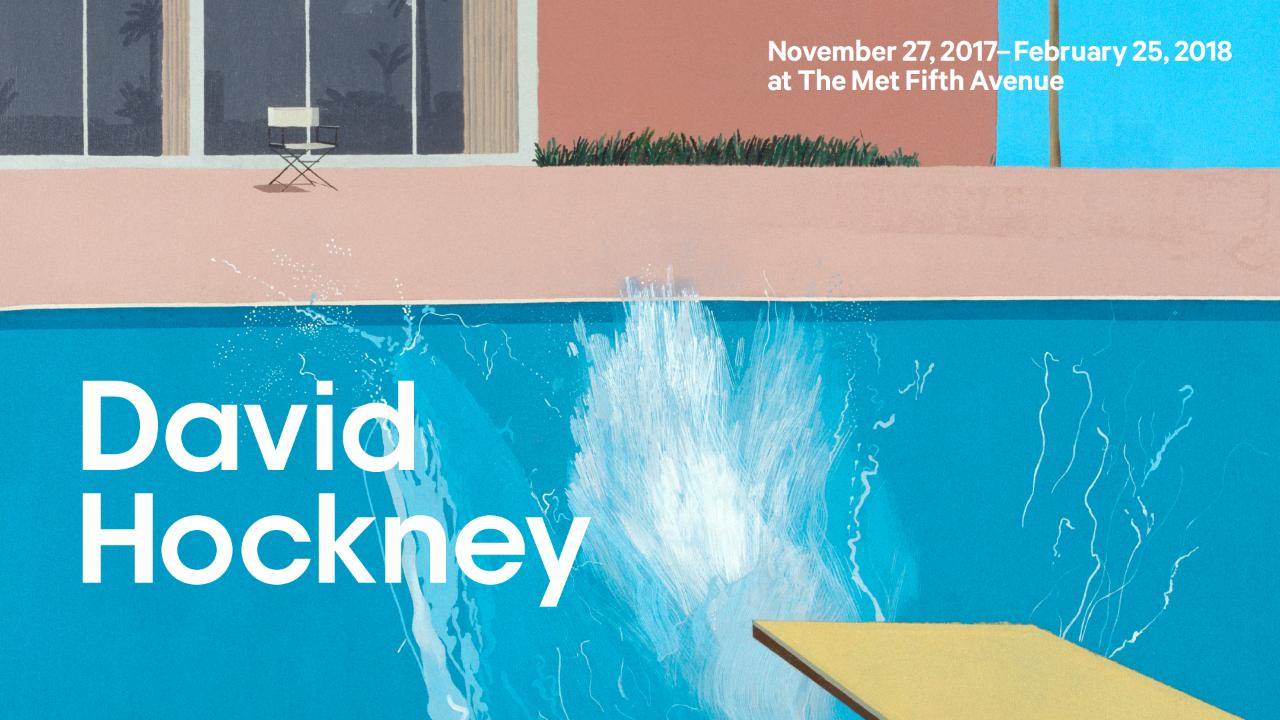

x. What story do we tell the mirror? Do we sing it love songs or deliver it an essay, dry and annotated, sober and coherent? My mirror is tall. My mirror is wide and long; it has untold depths. See, sometimes you can look in the mirror and see a face that’s not yours, or a face that was yours. You can, in a mirror, see behind yourself in ways otherwise impossible or very — highly, you see — unlikely. There is synchronicity in our reflections; yours looks to be yours just as mine appears to be mine. x. I am slowly becoming better at looking at myself. x. The story of the mirror is the story of myself inverted. I was the first and third born. I never left home and there are no windows in my childhood bedroom, in fact, there are no windows anywhere in my life. x. The mirror and the window play prominent roles in the work of one of David Hockney. David Hockney and voyeurism are me and voyeurism, are me and my substances, are me and my self when under the influence of love and leering eyes. They addict (they yearn) for a subject; the subject is everything and empty. Hockney and reflection are the heart of the matter, something like a raison d’etre, and he has introduced us all to the colourful yet monochromatic, the blurry yet separated, the balanced yet falling apart, the single sourced, the placid, the mysterious, the awake and daydreaming. He has explicated to us our culture's concept of calming down, and, vitally, ideas of what success really felt like for affluent white cosmopolitans. A riff, a portrait of his portraits: affluent white cosmopolitans: queered and pastel, permitted and flaunting, flat and flaccid, naked and bitter, fists dripping in anger, glass jaws supporting eyes in a directed gaze, (panelled portraits of these orchestrated gays), moments extended, the glance here lengthened into a piece of unchanging, static art. It is the opposite of animal and is animal. These are charged instances rubbed down, reanimated, forgotten again, then made to emerge as a moment and a memory of a moment. They have history and future, they tease the surreal (they mock it really); they own sex (they unown sex), and, accordingly, hold each of us accountable. His work cares nothing for you and his subjects care for nothing. Someone, namely Hockney, discovered for us the beauty (could you call something pink and teal profound?) in the vapid, the depth that rests in our peering vacuous eyes. Someone, namely Hockney, discovered for us the beauty in the elevated, the depth that rests in the shimmering that makes us up. x. We are all visitors to and with one another. We pass through each other’s lives like sunlight through sun-facing windows; we take some things and we leave others. In our wake are scars and marks and bruises and pain but also warmth. Our compensation is constituted by lessons and diatribes and ideas and ideals. We move often in tandem but are always approaching a point of divergence, a split in our paths, and this is good, is okay, is natural, is true. As I reflect on a Hockney from my history — a piece that is only still somewhat with me, a piece with three planes and three mirrors and a single light source — I am reminded about the days when I would dance in front of my twin brother’s mirror, naked, the opposite of hirsute, dangling, passionate, a wannabe Hockney subject without those words to know it, addicted. Was what I saw a little boy or a fierce subject, and did that mirror lie to me as a gym scale lies, was it tall, wide, with untold depths? x. My roommate is surely at home, staring in our very tall mirror. The reflection in the mirror is not whole; the person you are (and the person you are with) does not exist in full; we get fragments, only, of each other and we construct around these fragments ideas of people, of personhood. Varyingly: we lionize and we ridicule. As people round out, as they became more to us, we are compelled or repelled; are drawn in or drawn out. This is the getting to know phase. Hockney is benevolent: he allows us, in his figures, to see the shapes that form their foundations. The cubes and rectangles and spheres and ovals that compose us, our personhood, our bodies, them and their bodies. Our skin and the bones on which they are tendonly grafted are brought forth in his work. What happens when we get close to people, when we “open up” to them, is it that we are displaying to them the shapes that form what we think (and therefore actualize and know) to be our selves. There is a beautiful geometry to the manner in which we become intimate, how the slope of shoulder meets the curves of neck, how what we share and what we express and what we are fit snugly next to one another such that we become a composition. And in these Hockney subjects that geometry can be undone, and then may only be suspended in the moment that is captured in the work. Remember: Hockney has left hours of canvas undisturbed, as the spaces that are inconsequential to the geometry of our lives are not his concern, or, make up a different composition, still an elegant, lively geometry but blind to the subjects at hand. x. A triangle resides between us; its three points: the voyeur, the representative, and the reflection. Maybe this triangle extends and envelopes us, is a fence or a boundary, a law in which we are stuck and subject to. We slip from corner to corner; at times (at certain points) we cower and crouch and nestle up so closely to the walls of this structure that we forget they exist or can be transcended and escaped. This triangle is a pool suspended in splash. Is a swimmer submerged and unmoving, glanced down upon by a wealthy white cosmopolitan, whose blonde hair holds more volume than the rolling LA hills behind him. Hockney has, absolutely — unbelievably — discovered a depth and heart to the spoils of high society, that is, frankly, repulsive, that imagines it is everything and is in fact nothing and perhaps operate as a net-negative. But he’s discovered something, and it is moving. x. There is reflection surrounding us, chasing us. It sits (so charged) everywhere; it glances about every which way and it has, always, something to say. Life is but a collection of mirrors and windows and spit-shined marble and plastic-fake leather patterned with our reflected faces and there is nothing we can do about it. x. Hockney painted from postcards and nature magazines. His reflections are repurposed reproductions of images and stills and worlds and landscapes that may or may not have existed: there is value in the intangibility here: what is abstracted more than once is then again a real object unto itself. x. How do we avoid writing, even in brief, about Hockney; I am flummoxed. x. A third device in Hockney’s work is a confluence of the first two: the swimming pool. Both reflecting and allowing our sight to pass through; both distorting and revealing; both deep (owning depth) and immaculately flat. x. I had great difficulty getting dressed today, this morning. Maybe it was a hangover debilitating my tastes and confidences. Or perhaps it was my capricious mirror that kept rejecting my humble attempts. Perhaps, more, it was Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist telling me to do better because the issue pestering me was one of texture: how to complement different fabrics in my clothing; the (utter and urgent) importance of flatness as juxtaposed by depth, of cotton flouting wool, of soft sitting under (and distinguishing itself from) an overly starched collar. The shapes that make up the whole, my geometry I am getting to know but, now post-Hockney, may be my unbecoming. x. Beefcake magazines and hypnotists; swimming pools and suspensions of emotion. I had a beefcake magazine, a shrink, the image of a swimming pool and suspended emotions, and I fantasized - inspidly, unknowingly - about being a Hockney subject. x. Voyeurism, but consensual: telling someone that you want to (erotically) watch them from afar and having them in reply nod and say okay, alright, what do you want me to do? To establish intimacy via distance, ignoring fingertips in favor of eyelashes, to be within someone but only via their lingering awareness of your gaze. x. Hockney cashes checks on the fact that we all want to be there, at the pool, shirt off, carefree. He reveals that all of us: we wish to be watched. x. Remember my quest to see myself better? Remember that the mirror inverts my history and the type of blood that flows through me and, even, sets its own course, even, establishes addictions. I wish to be watched and I wish to imbue intimacy. We wish to be watched. The genie in its shiny bronze lamp (maybe this lamp is aquamarine and resting in the bottom of a swimming pool nestled into the winding LA hills) announces itself (bright blue) and grants you three wishes. You, desperate, use two of them to be watched: first by Hockney, of course, and then by the rest of the world. You hold onto your third wish closely, having slipped it into your chest pocket, you pat it as you pass through doors, as you peer out windows, as strangers bump into you on the subway. One day it will come of great use and the whole world, Hockney (emphatically) included will be witness. x. In Hockey, one can always count the plains — do it yourself it’s fun and will impress your friends — but they are there to establish the space between you and these lives, which is exclusive and imperious, yet generous. It’s a warning, not an invitation, though it’s seductive, as these things are. Most good art warns you in some manner. Compels you away from something you now know (perhaps have long known) to be unseemly, to be unjust and unattractive. Hockney, in his mysterious, is generous. x. If Hockney painted a park in New York City it would not be one in Queens or Staten Island (though they have a great many parks, a great many sights and peoples) but, rather, it would (certainly) be either the southwest corner of Central Park (Columbus Circle) or Washington Sq: the lush greens preserved yet set aside, the concrete within and above and surrounding, the stone smooth and there to sit on and photograph (but maybe only for people of certain tastes), the dirt kicked up and stuck within shoes, a place of activity for those that wish to be like a Hockney, watched and quietly violent. But we prevaricate and are soon to return to the park, not a park, but the park, where we will together and in tandem, in perfect harmony, watch the people as they move about. Aron Canter and Holden Taylor Aron Canter and Holden Taylor collaboratively write essays off a single word document, so the essays are a document of performance as much as a realized piece of non-fiction. Their interest range from syntax and language, to criticism and humour, to impact and meditation.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|