|

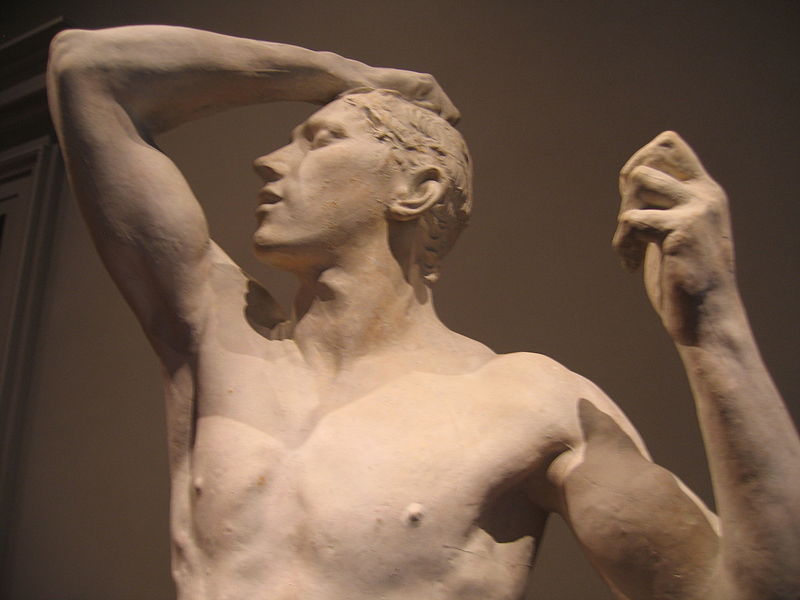

Our Man in Beauvais In October 1930 my grandfather travelled to northern France to report on the crash of the British airship R101. He'd been to Paris just once before, so spent the last of his four days there, devoting the first three to the disaster near Beauvais and its aftermath. On the third evening, booked into his city lodging in the 18th arrondissement, he got into conversation with the owner, who asked him if he liked the work of the sculptor Rodin. On the walls of the small downstairs bar were photographs of Rodin's statues among old lithographic posters and some amateurish oil paintings of the Left Bank. My grandfather was forty at the time and a freelance journalist. He'd been commissioned by the Illustrated London News to cover the accident but had also contributed essays and reviews to the magazine on art, especially of the European modernists, among whom his favourite was Giorgio de Chirico. He had recently written about a de Chirico exhibition for another publication, the Burlington Magazine, and admired the artist's eerily deserted streets, thinking them prescient. Anyway, my grandfather having divulged his reason for being in the country, and his interest in art, the landlord told him that he might like to know about a neighbour of his called Auguste Neyt, who had been the model for one of Rodin's early sculptures, the 1877 Age of Bronze. At the time, Neyt, a Belgian soldier and telegraphist, had had his photograph taken by Gaudenzio Marconi in order that Rodin could disabuse a sceptical art critic who had suggested that the sculpture might have been made from a life cast. 'How old would Neyt be now?' my grandfather asked. 'Old,' the landlord emphasised, scouring with a tea towel the inside of a glass. 'Très vieux. He used to come in here now and again; but I haven't seen him for weeks. I think he's still around, though.' (I can recall almost verbatim the way my grandfather told me this story. I'm guessing at precisely what was said, but he was a great one for encouraging the gist, or what he called 'the decorated truth', which also served as his definition of art, but never of reportage, of which he was a stickler for unadorned accuracy. He would have been pleased to know that I was keeping his tale alive.) The next day, my grandfather asked for directions to Neyt's rooms, thinking he might be able to return home that evening with two stories. He walked there with the images of the airship crash site vivid in his memory. He'd telegraphed a preliminary report and had written up much of a longer account. It was the flimsiness of that mighty dirigible that had shocked him. A few hours into a flight to India via Egypt it had gently nose-dived to the ground and caught fire, killing all but eight of the fifty-six aboard. He'd expected to see smoke-blackened bits and pieces scattered over a huge area like the skeletons of a host of upturned greenhouses, or a dispersal by the wind of some ruined crystal palace; but the effect was of an implosion, concentrated in a small area. On the farthest perimeter, away from the little knot of police, reporters, and official investigators scrubbing the crash site like a buzz of flies around a cow pat, he'd made an astonishing discovery: the charred body of a man, alone in foetal position and unrecognisable. * Well, Neyt would have been old but not ancient, my grandfather thought – seventy-five to be precise, and probably still clinging to some vestige of fame by association. Rodin had died thirteen years before at more or less the same age. The photograph was almost as impressive as the sculpture: it was a study of strength and unabashed manhood, the whole effect skewed by an attempt at grace clearly posed to mimic the finished bronze. Despite his compressed musculature, Neyt looked curiously vulnerable, as naked an illustration as one could want of Franco-Prussian cannon fodder. After climbing three flights of stairs, my grandfather arrived at the apartment and knocked at the door. Inside, he could hear bronchial coughing. There followed an exchange between a man and a woman, the dialogue combative, the woman's voice growing louder as she came forwards and opened the door. It was as though a curtain had been drawn across the threshold, but it was not a drape but the woman's torso. She was bare from the waist up and comprehensively plastered in tattoos, her outstretched left hand holding a flat-iron. My grandfather admitted to me that his French at the time was comically literal. He addressed the human tapestry standing before him: 'Bonjour, Madame. Je suis un écrivain Anglais. Est-ce que je peux être autorisé à parler à Monsieur Neyt?' But before he'd finished, and looking beyond her, he could see his quarry. Neyt was sitting between a basket of ruffled clothing and an ironing table, near which was a column of pressed garments. The woman said nothing apart from mumbling an introduction to Neyt, tacitly inviting my grandfather in with a rapid jerk of the head. He did describe the conversation he had with Neyt as the woman – 'a stranger to modesty', was how he put it – continued her chore with frequent visits to the fireplace and repeated thwacks as her iron hit the table. Perhaps the two were used to such inquiries. My grandfather: 'You posed for the great Rodin.' Neyt: 'Mmm. You have cigarettes?' My grandfather: 'I'm sorry. I don't smoke.' A pause. 'Did you sit for him often? What was he like? Quel genre de personne etait-il?' His use of the word sit – asseyez – appeared to confuse Neyt, who probably always stood; that's if he did so more than on that one auspicious occasion. Neyt called to his companion: 'Zure. Le photographe.' The woman was well named: Zure. Azure. The tattoos reminded my grandfather of the sea: forms and images floated in a wet and rippling cerulean ocean-sky. She rested the iron, which hissed an objection. From a drawer she retrieved a small sepia photograph. She handed it to my grandfather, standing before him with full, pendulous, decorated breasts, and the first motions of a grin at his discomfiture. At the end of one of her nipples was what he soon realised had been a droplet of milk; when he next looked it had gone. It was an original print, well-thumbed; perhaps the original given to Neyt by Marconi or Rodin himself, and a smaller version of the landlord's. As my grandfather looked at the photo, considering his subject to be taller than he, the man himself rose unsteadily to his feet, but not to the height expected. The thump, thump of ironing continued like some attempt at resuscitation. Neyt seemed the epitome of decline, a man bent and struggling for purchase on the relentless slippage of time, silently holding out against further loss – of weight, height, and dignified bearing. In grubby moleskin trousers with braces, and a loose-fitting vest that he once must have stretched to tearing point, he was now round-shouldered and beyond any physical virtue supported by photographic record. The print showed a body taut with almost violent potential, but now only his forearms, as fibrous as tied bundles of sticks, remained unchanged. * My grandfather did write a story about Neyt but the publication in which it appeared reduced it by half and published it down page, declining to use Marconi's picture, or a picture of Rodin and the sculpture, or a picture of Neyt he'd taken with his Nagel/Kodak Ranca camera (Neyt's partner refused to pose; she would have been picturesque). The photo of Neyt taken by my grandfather was at the end of a roll of crash site horrors. He told me that the only mark made on the ground by the R101 was a groove ploughed by its front cone on impact. Scrap merchants arrived to claim the metal. He visited the dead, laid out inside a building in two rows, like hospital patients during an epidemic. His discovery – astonishing to him - had been made well away from the crash site. No-one identified the body. Police assumed it to have been an itinerant male, idly crossing the field as something awful and monstrous came lumbering towards him out of the skies after he'd been alerted to its low distant rumbling; he'd caught fire but managed to struggle to where my grandfather stumbled upon his Pompeiian form under a hedge and took a photograph. To that one collateral victim must have been vouchsafed an image of what death would be like, if he'd ever given it any thought. Towards the end of his life my grandfather was seated and silent. He hated conceits and coincidences, which he associated with sensational journalism. His discoveries of the ageing Auguste Neyt and that burnt body, examples in the wider world of what was coming to the passengers and crew on the airship, what in fact was coming to us all in one form or another, were entirely separate happenings and he kept them separate, even writing about the unnamed drifter as a panel within his main story. Among the pictures on the wall at his home were a framed photograph of Neyt (a copy of the Marconi original), and a reproduction of one of de Chirico's desolate urban landscapes. As he, too, approached death, brought to frustrating immobility by motor-neurone disease, I couldn't help thinking that de Chirico's cityscape emptiness now reminded him of an opportunity missed: of recognising in chance occurrences and fanciful images a link, a reminder, a nudge, an intimation of mortality, which might offer a sober view of those events and promises in life meant to excite or enthuse us. He left me the small, white-bordered photo he'd taken of Neyt, and I have it in front of me now: it is Neyt slightly out-of-focus, off guard and forgotten, except by the camera's decisive moment, for which its subject summons the hint of a smile. I am the same age as Neyt was in 1930: très vieux! My grandfather was cremated after a humanist funeral service, at which I spoke of his visit to Beauvais and its unintended consequences. The crematorium was packed. I hadn't realised how many in his profession had thought well of him. Soon, it will be time for me to go too, if the predictions are right – they usually are. I say no more, except that I have known for some while. Nigel Jarrett Nigel Jarrett is a former daily-newspaperman. He won the Rhys Davies Award and the Templar Shorts award for short fiction. He's written five books and also writes for Jazz Journal, Acumen poetry magazine, the Wales Arts Review and many others. His work is included in the Library of Wales's anthology of 20th- and 21st-century short fiction. He lives in Monmouthshire, Wales.

3 Comments

David Dabliu

8/13/2022 04:10:37 pm

Thank you for sharing your father's colorful story about Auguste Neyt in the twilight of life. At first, I was disappointed that you did not include the photo of him from that encounter. Then I understood that his natural youthful beauty had been immortalized by Rodin and Marconi—and that is how we and future generations will remember him.

Reply

David Dabliu

8/13/2022 04:14:05 pm

In comment above, I meant your grandfather, of course.

Reply

3/7/2023 09:51:14 am

Hi David.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|