|

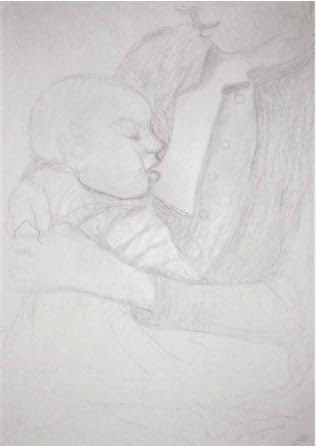

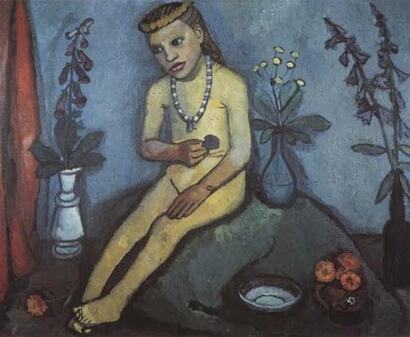

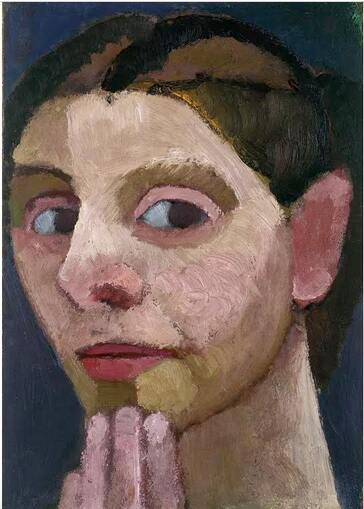

A Letter from Worpswede, February 1905 Milly, if I had made three good paintings in my life I could die now. But I haven’t made one. In two days I’ll be twenty-nine. Dear sister, how good you are to believe in me, or want to, even in this dull time when I have no proof of any becoming, except what the family calls my arrogance. I avoid the studio now, eight years of oils and sketches stacked against the walls. Study the masters, Father said, meaning you will never be one, meaning revere technique to learn some humility. Otto tells me: learn to draw. I want to say Otto look at your hand, do you see lines around it? If I have masters, they are not the great Germans anymore. I’d go back to those ancient anonymous makers of the unforgettable dark eyes awaiting eternity. Or follow Cezanne who alone sees that color is truth and that’s what painters are for. Why, to be, must I be willing to be unkind? Well I must be, and I am willing. Oh Milly, I’ll be all right. I get like this in February when spring and Paris are too far off and my brushes turn stiff while I sit on the opposite end of the couch reading in French and Otto makes entries in his notebook entitled “Ideals” and had no idea yet of my travel plans. I want to be equally unaware of the way he turns his pipe to the side to see the page, how he turns out studies day after day and will overpaint, not realizing the studies themselves are lovelier than anything that buys us food. If only the sun would come out, I’d insist on a skating tour in the bright cold. You see? It’s only my old winter mood. ** This poem was previously published in the anthology Sister Stew: Poetry and Fiction by Women, Bamboo Ridge Press, 1991. ** Becoming Something (Letter to Otto Modersohn) How I loved you, Dear Red. Don’t send my own letters as proof. I called you my King. I gave you my whole round soul but I need it back. If you want me to write to you now it must be about art. I don’t even know how to sign this letter. No longer Modersohn. Not Becker either. I’m nothing until I create colours as dazzling as skin in sunlight, a pious nude from the concave side. I have begun. I once was a little green kite you flew on the moor. Unused to thin air I bobbled and trembled at first, kept dipping back down toward the birches, the small black sails of Worpswede. But I’m finished with brooding. My colours change in this atmosphere. A yellow coltsfoot held toward the sun gives off its own light. I’m soaring again Red Beard, this time with no string. I see you now only because I know you are there. But I can see Paris, the world, from here. Infant Nursing: Sketch by Paula Becker, 1902 Not beautiful this baby, but intent on satisfaction. In the centre of this portrait his lower lip protrudes, its wet inner rim supporting the nipple pulled and elongated by his tongue. Eyes and mind are shut. He is his mouth and all that milk is becoming him. The strongest lines form contours of his head, his cheek, her breast, his lips, her lips. His infancy is round. Maternity is round. Her tender concentration, one arm cradling the surprising heaviness of his head. Like him she will not move until he’s had enough. She strokes his cheek with her rough thumb. ** This poem was previously published in Virginia Quarterly Review Autumn 1989. Young Girl with Flower Vases No one will tell this girl to put others first or give her words to be read in silence. No one will cover her up when her father enters the room. Clothes for her will be merely ceremonial ribbons for the soul. This is no child to play with. Consult her about grave things: how long you may have left and whether your father ever will acknowledge you. She’ll respond in a yellow-petalled whisper and can no more be wrong than sun can on the roof or some leaf we can’t identify. ** “Young Girl with Flower Vases” was previously published in the anthology Sister Stew: Poetry and Fiction by Women, Bamboo Ridge Press, 1991. Self Portrait with Hand on Chin, 1906/07 I catch these eyelids under putty brows with seven strokes of dusky flamingo, sunset yellow rose. Her eyes, though they have lost their curiosity to a sort of chalky needlessness, keep gazing after something on my right. I try moving so that something will be me-- farther and farther over, following, until I’m even with the edge. They look still farther. At last she is simply unaware of me. What is that look? Something rising wonderfully open-eyed but without urgency, with hushed authority, as if from Egyptian tombs. Already settling into a thick and thickening yellow-green, her lips are slightly pulled apart by her own fingers before they close again and she begins to hum from everywhere, a living stone. Sue Cowing Sue Cowing lives in Honolulu where she taught history and Asian Studies for sixteen years before leaving teaching to write. She has an MFA–in-Writing from Vermont College, and has published poems in numerous journals and anthologies including Virginia Quarterly Review, Cream City Review, and The Denny Poems. Her books include Fire In The Sea: An Anthology of Poetry and Art (University of Hawai‘i Press); My Dog Has Flies: Poetry for Hawai‘i’s Kids (BeachHouse Publishing); a novel, You Will Call Me Drog (Carolrhoda Books and Usborne UK); and The Octopus of Imagination, a chapbook of her poems self-published during COVID shutdown.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|