|

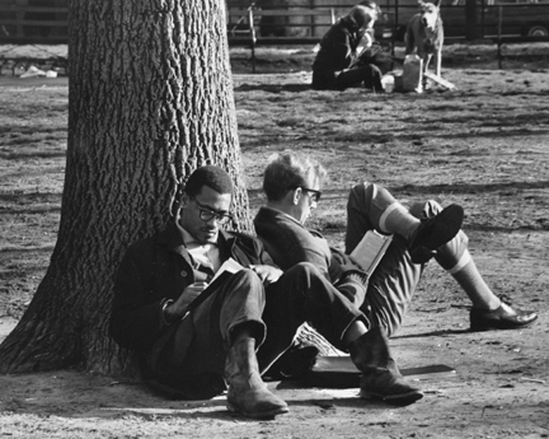

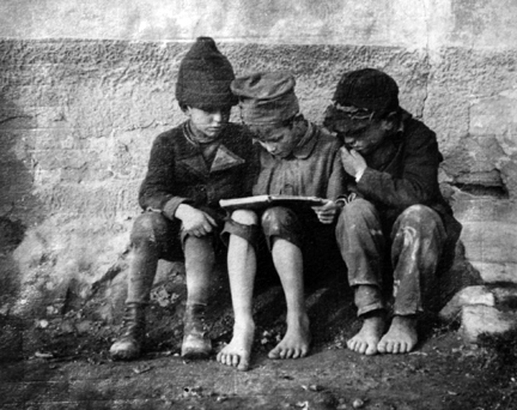

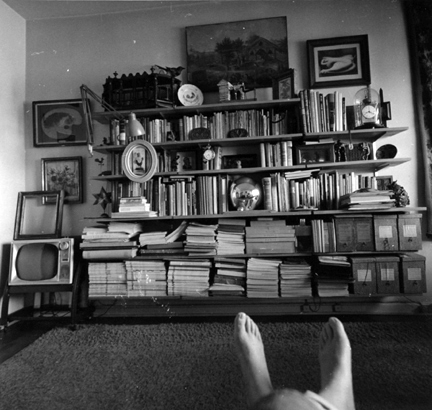

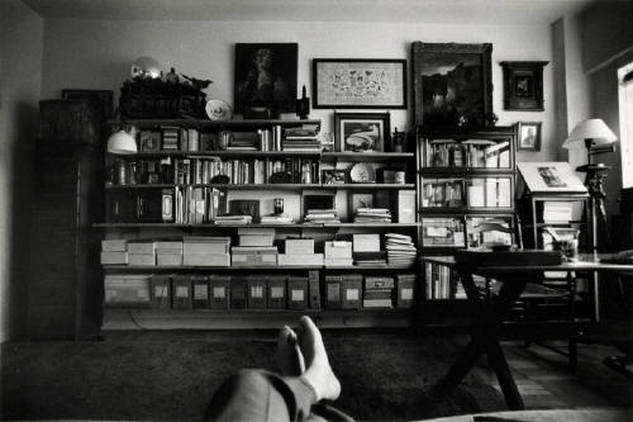

Reading Kertész Books absorb us, draw us inward— even when we’re most in public. The great photographer André Kertész made a lifelong project of exploring that paradox. Between 1915 and the 1970s, he travelled the world, snapping candid photos of people with their books, their magazines, and the occasional newspaper. On rooftops, behind stage doors, on trains, in parks, in bars and shops, bent over trash bins, tucked into alcoves; black and white; male and female; priest and rabbi and nun; rich and poor — wherever he found readers, he recorded them in the act. Reading is the great leveller, the great lifter, his images seem to suggest. In the republic of books, we are all equal. There is something almost unbearably poignant about these photographs today. Yet, what we sense when we look at them is more than wistfulness for an imagined past, more than mere nostalgia. Shot from unexpected angles, they conceal complexities; often we have to work to discern a subject within the frame. The experience mimics the act portrayed. In these images, we don’t simply witness someone reading; instead, we read someone reading. So what we feel when we look at them is something akin to deep reading’s deep engagement. Only a lover of books could take such photographs. Kertész could hardly have been blind to the irony of that. For it was brilliant photographers like him who were rendering text increasingly redundant in his day. “Your pictures talk too much,” said an editor at Life, in rejecting some of his images. Kertész’s photos were so expressive, so complete in themselves that they left nothing for a journalist to say. Some of his photographs seem to acknowledge as much, and to draw the implications even further. One in particular, taken in his study in 1960, is a kind of oblique self-portrait. Shot from a sofa or chair on one side of the room, it takes as its subject a wall of neatly arranged shelves. In the foreground we can see the photographer’s bare feet. Those feet by then had transported Kertész from the ticker-taped floors of the Budapest stock exchange, where his family had sent him to work as a young man, to the absinthe-scented cafés and paint splattered artists’ studios of Montparnasse. Later still they had explored the fire escapes, rooftops, and windowsills of New York. At the same time, they recall the dirty, naked feet of the young boys poring over a book in one of his earliest photographs. At sixty-six, he had not forgotten his beginnings. The objects on his shelves evoke a full and cultured life. Books. Magazines and journals stacked in piles. 19th-century landscapes, dark and moody. One of his more surrealist works, from the Distortions series, hangs in the upper right; below it a glass-encased clock indicates the passage of time. A mirror reflects the artist back to himself; a lamp casts light on the portrait of a woman, possibly Elizabeth, his beloved wife. And amid all this evidence of a refined and cultivated sensibility squats a television. Its screen is blank. Above it dangles an empty picture frame. It is tempting to see that television as an evil dwarf in a tale of loss and bitter discouragement. By then, Kertész had lived in the United States for more than twenty years, and he had failed to achieve any recognition as an artist. Too late, too late, this image seems to say. As photography had overtaken books, so television might overpower photography. And the world would turn, increasingly, to flat and featureless screens for instruction and entertainment. Kertész didn’t live to see the spread of computers and Kindles and smartphones, and it’s difficult to know what he would have made of them. For if he sometimes seemed to dread the march of technology, he also embraced its advances; one of the earliest photographers to adopt a 35 mm camera, in his old age he also experimented with the latest Polaroid. What’s more, as the father of street photography, he was always eager to take pictures of ordinary people going about their lives. In fact, if he were still at work today, instead of readers, he might be snapping candid shots of men and women leaning over their laptops or fixated on their smartphones. But, “I do not document anything; I always give an interpretation,” he once remarked. So I doubt if his laptop series would have anything to say about stillness or deep engagement. Then again, better than anyone, Kertész understood that we live in a liminal time. Screens may seem ascendant, yet books and words can still command a central place. A later photo from his study series illustrates. Taken in 1969, shot from the same sofa or chair as the 1960 picture, it depicts the identical set of shelves; a viewer will also recognize many of the same books and pictures and treasured objects, along with the same bare feet, crossed in almost the same pose. But that is where the similarities end. In this photo, to the right we see the table where Kertész does some of his work, along with a tripod. In this photo, the photographer’s own photo, his Distortion, occupies a more central place on the shelves. And in this photo, there is no clock, no television, and no empty, dangling frame. Instead, the artist’s neatly organized books and papers dominate the scene. By then, Kertész had finally achieved the American recognition he had long desired, and I like to think that with revived reputation came renewed hope in the rich hermeneutical tradition from which he sprang, and refreshed belief in the power of the word and the power of artful arrangement.

He must have sat on that couch or chaise almost daily for decades, and almost always with a book. But he did not take a photo every time. What, then, prompted this particular self-portrait? We’ll never know. Perhaps a shaft of sun fell just so across his page, distracting him; perhaps a memory, called up by the story he was reading, momentarily tugged his attention away from the page. Imagine. At seventy-five, he is white-haired, balding, age-spotted, mole-scattered—marked by time, just as his room is marked by time—and the feet stretching out before him ache from his morning’s walk. Outside, in Washington Square, the sounds of a guitar drift up towards the window; closer, in the kitchen, Elizabeth shuts a cupboard door and then begins to hum. He thinks about their evening meal—baked fish, perhaps, with a simple salad and baguette—something light and fresh to mark the season. Soon, he’ll open a dry Riesling and pour them each a glass. From their small round table, they’ll see the trees in the square below and the crisscrossed pattern of the pathways. Before the stock exchange, before the war, before photography found him, he used to fish the Danube. That was in childhood. Sun glanced off the water, making him squint. Drifting, dreaming, sometimes he’d wait for hours for a tug against the line. He laid the catch inside his uncle’s wicker basket. The larger carp would thrash against its reed-lined sides. The most valuable things in a life are a man’s memories. And they are priceless. He looks at his familiar shelves. Perhaps he recalls his father’s bookshop, back in Hungary—the country he fled, first in pursuit of his art, and later, to escape Nazi persecution. The moment always dictates in my work. So much history embedded in those carefully arranged lines and planes. So much life within those assembled pages. So much life in all pages. The novel in his lap, for instance. Words, like light, bracketing moments; words, like light, calling forth worlds. Everything is a subject. Every subject has a rhythm. His hand closes around the camera’s familiar weight. The viewfinder frames the scene. Seeing is not enough; you have to feel what you photograph. The shutter clicks. I write with light. He sets his camera down. Then he turns back to his book. Susan Olding Susan Olding is the author of Pathologies: A Life in Essays, selected by 49th Shelf and Amazon.ca as one of 100 Canadian books to read in a lifetime. Her writing has won a National Magazine Award (Canada), and has appeared in The Bellingham Review, The L.A. Review of Books, Maisonneuve, The Malahat Review, The New Quarterly, and the Utne Reader, and in anthologies including Best Canadian Essays, 2016 and In Fine Form, 2nd Edition.

2 Comments

Janet e Smith

12/12/2016 05:20:23 am

Beautiful, Susan. Thanks for choosing this, showing teh photos and your thoughts.

Reply

Eileen Mackenzie

12/17/2016 02:14:01 pm

so poignant especially in these days where text messaging and the kindle usupts books

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|