|

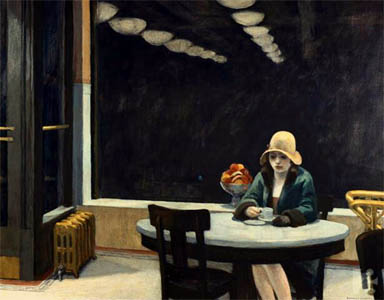

Reflecting On Loneliness It was in the news today- again- science has proven that loneliness kills. I suspect that this was a surprise to no one. And the lonely people flooding Facebook posted it with comments that reflected nothing less than accusatory glee. There was a gloating surrounding the story, a kind of pathetic, desperate jabbing meant to declare with neon lights the truth found in the findings. People are lonely, the lonely shouted, and it’s all your fault because people like you just don’t give a shit. No one got lonely from loving too much, someone commented after the story, and I felt the cold sea that engulfed him, keeping him apart from the strangers who didn’t know he was alive. I felt an icy flash of that dark place he was writing from and my heart broke for him. But loneliness has a different face for everyone, and where I stand, it looks an awful lot like love. Speak for yourself, I thought, with sorrow that is usually more contained. Loving too much is exactly what has made me lonely. Another person commented on science by citing facts that were really pure speculation. Women are lonelier than men, they said, and black people are lonelier than white people. Poor people are lonelier than rich people, etc. This was in stark contrast to another posting that knowingly expounded on the happiness of poor tribes in Africa and destitute families in Cuba and Mexico. When you have nothing, you realize what you have, the person said, and those of us steeped in privilege and consumerism in white North America cannot possibly comprehend community and its value. Cubans know the meaning of family. I don’t know. I love living alone. Sometimes I am heading home from a grueling social soiree and panic, thinking, what if I had a roommate or kids and wouldn’t find solitude when my door shut on the world? I often quip that when I find the man of my dreams, he will live next door, even if we are married. I’m not the only one who finds overcrowding annihilating. But apparently, say the wise men of science, flying solo is as deadly as being fat or smoking, and it causes heart disease, immune deficiency, high blood pressure, hormone disorders, and dementia. It was a bit of caustic serendipity, perhaps, that before logging online this morning to find this story I waited for the coffee to brew in a quiet automat painted by Edward Hopper. Most mornings, I open one of my art books at random and contemplate a painting in those few minutes before the day begins. Today’s page turned out to be a familiar and favourite work by an artist dogged by interpretations of isolation and desolation. Hopper was a taciturn and ornery fellow but he resisted our translations of his work, however entrenched they have become. Hopper’s art most famous work, Nighthawks, is literally the poster child representing lonely. A few stragglers sit in a night café or bar, staring into the stillness. We can barely abide their lack of conversation or their late night solitude and have created a persistent mythology about the painting. Automat, 1927, features a young woman seated at a round table our side of a huge dark window. Like most of Hopper’s works, it is interpreted as a lament to humanity’s terrible disconnection. A typical conclusion is this one, from an anonymous writer online. “The woman looks self-conscious and slightly afraid, unused to being alone in a public place. … She unwittingly invites the viewer to imagine stories for her, stories of betrayal or loss. … Hopper does not tell a story but paints a moment, a moment that includes loneliness, isolation, and a spell of the dark…The viewer looks at this and immediately feel her isolation and loneliness as if it were his own.” When I was a teenage outcast, I was so lonely that I couldn’t comprehend how much worse my condition could and would become. And I loved this painting. But it wasn’t because I felt the subject’s loneliness so deeply. It was envy that I felt. I was madly jealous of what she had. There was a casual resignation in her expression. In Hopper’s picture, I didn’t feel the ongoing chaotic desperation that was all I knew. I didn’t read into this work the cues of hopeless isolation I was supposed to see. I felt instead someone else’s Zen, before I had even heard of the concept, a calm from the storm of others. I constructed a whole life for this character, the woman with the fine calves and the beautiful cloche, whom I named Jane. She was an artist. She lived with her father, and her mother had passed away. She was Catholic, but only at weddings and funerals and maybe Easter. She was a young woman who had experienced tragic and epic romance. She was also ordinary, a woman patiently waiting out the day with a cup of coffee. My imagination imbued her story with a poignant poetry. I thought that if I could find hats like hers and the peace of mind to sit so solemnly alone, I would always find my way. By the time the coffee maker breathed its contented and finished hiss, I was long transported into Edward Hopper’s painted café. I had already lamented the thick calves and crows feet of middle age that wedged twenty years between me and the last time I’d seriously searched this artwork. And I’d already been struck by thoughts that were bizarrely protective of the young woman’s solitude. I had woken alone and I would spend the day working, alone. Even so, I wanted to hog the woman’s solitude like a cache of diamonds. Then I logged into my morning, Stevia and cream tempering the acrid and acid Maxwell house bargain canister. Lonely! Lonely! screamed the news. You’re dying of loneliness! Simon says, science says. Perhaps what is loneliest for the introvert, who now has a name and a category from which to perch piously, is not being lonely. It’s practically a sin. Who in their right mind would envy, over Christmas, those with no family rigmarole to attend? Who but the most selfish and miserly among us would prefer to wander aimlessly by themselves on Saturday night, when a gaggle of girlfriends was cheering and beering together in the local watering hole? We are monsters, refusing the calls of people who love us and want to chitchat until the cows come home. Inane banter does nothing to assuage the hollows, but long hours walking solo restores our souls. How do you explain that you need more “me time” to people who would give anything for more anybody-else time? My extroverted sister makes me dizzy, and the kindness of strangers who reach out into the deserted geography where my mind resides is one I can’t always repay. My work, too, demands so much interaction that I have to steel myself to keep it together. Yes, writing and working in the studio are done in long stretches of gorgeous solitude. But the other side of my job is about attending art openings, mine and yours, meeting and greeting and mingling and jingling. In occasional doses, the jazz and white wine and meet and greet of this scene is nice work, if you can get it, and a chance for me to wear my red lipstick for someone other than my cats. But too much of this on my calendar, I begin to defragment and come apart at the seams. Perhaps it is true that introverts are insensitive, self-centered clods who don’t give a rat’s ass about the brotherhood of man. But I suspect something else is going on for those of us who take our company in smaller doses. We may be more sensitive. I am so sensitive to the emotions of others that I can hardly take reign of my own. Being highly empathic is, indeed, a trait that fuels the work of many artists and writers. We must constantly create because we are always “processing.” Far from self-indulgent, we are stuck feeling and feeling and moving through everyone else’s ups and downs as well as our own. It’s a heavy burden to carry. Following this logic, perhaps it is the “people persons” who need constant assurance of their place at the table, continual affection even if it’s from strangers, which makes it superficial even if it feels good. Maybe it’s these who are more selfish then, than us loners. We don’t need to scoop up a constant fill of emotions from others to feel good, to validate ourselves. Maybe the social butterfly is not the saint with endless love to give, but the piranha, with endless love to take. Or maybe we are all just wired differently and need to stop pointing fingers at each other every time an article is posted on social media. I always try to explain that I need a lot of “down time” in order to fuel up for the big gusts of loving everyone, and I take great cares to make sure that the people I love know my love is not a mild, airy, flaky kind of thing but something profound and loyal. It is not wasted on every Tom, Dick and Harry but reserved for the ones who grow with me and show deep acceptance and care. The biggest mistakes I’ve made in my life were the ones I spent distracted by and focused on emergencies of urgency for strangers and relatives alike, while ignoring the lovely, ordinary people in my life who loved me. My brazen errors of attention robbed those who were not fleeting stars on my path, but fellow travelers for the long haul. Still, I can’t help but resent the archaic views that the individual is to blame and the collective overrides the ultimate minority, the self. It is our unique individual identity that separates us from the animal kingdom, where the most personality filled cat or dog or cockatiel will never look into the mirror and say, who am I? When will I die? Why did this poem make me cry? Why do I prefer golf over ballet? Should I take up Buddhism? Pyschology keeps harping over the joys of any old relationship, and people who prefer to live alone or love alone are made to feel they are missing something, that they are decrepit, lacking, maladjusted, dangerous, or sick. It takes a village and such clichés are considered superior ideations, and retreat is antisocial and ill. But what of those of us who find the most healing in backing away? Are we always and forever retrogrades? More, are our intense social unions nullified by the lack of intrinsic need for constant companionships? Some of us get very tired of the pathologizing. We don’t feel incomplete. I have made peace with the fact that most people want to be paired up, or feel that a night without someone snoring and kicking next to them is an empty one. But I know that countless others aren’t lying when they find true fulfillment and relief in their own rhythm. How we survived the days of the cave, and the days of four generations in one kitchen all at once, I cannot guess. Perhaps I am grossly selfish, but the overwhelm of a big family would tip my mental health balance towards suicide, and quickly. It is not company that assuages these impulses for me: my lifelong struggle with bipolar disorder is always exacerbated by over-socializing and soothed by quiet time far away from the madding crowds. The impulse of j’accuse is universal, though, so when some feel obligated to point at another’s paucity of love and empathy as a cause of the world’s loneliness, it’s as natural as breathing. If only lonely had an easy solution. I was so much lonelier before I recognized my introversion. I often try to explain to others that I’m never bored when I’m alone but quickly bored if I stay too long at parties. We all have our limits and they are different. Without a few days of solo bliss I can hardly handle other hearts. After holidays with family I cherish, I need time off and working is like the holiday. But I do start to feel unloved after a week or so goes by without some solid meeting of the minds and souls of those close to me. Still, I feel most lonely when tossed into buzzing social milieus with people I barely know, not when I’m by myself. Small gatherings of a handful of good friends somewhere with wine and the possibility of hearing each other speak are golden. Some people need more, some a lot more. A very few people need much less, and more, or even any, is painful for them. I’m not one of these, but I do understand that hermits aren’t necessarily damaged. They are avoiding damage. Extremely solitary people have long had cures of companionship thrust at them by the well-meaning but clueless, and doctors used to force autistic children into hugging and false bonding. But it is the individual who should set the pace of how much company and touch he or she needs Scientists and other social philosophers will always come up with their own prescriptions of what is normal and healthy. I can only go with what works in my own life. I have felt such intense pain in my lifetime, I sometimes don’t know how I still stand. I do not say this to separate myself from others, but rather to glue. We all feel pain. Mine is mine, a private affair, and yours is yours, and if there is something I can do, I will. But I don’t presume that there is, and I’m certainly not vain enough to think I can make it better just by being around. In my book, loving someone doesn’t mean hogging all their space and time in the name of “giving.” “Being there” doesn’t mean literally being here, at least not for me. I am moved when someone wants to “be there” for me, and knows they don’t have to “be here” to “be there.” The ultimate irony, perhaps, of loneliness, is that no one can fix it. It’s not so easy as stopping for a moment to consider the homeless or broken. It’s not about finding a party for a socialite or a friend for a widow. Even the most extroverted, social animals among us cannot find solace in a crowd after a death or separation. That demon of isolation and grief comes at us after loss, even when we have other magnificent offers. How many times have we squandered affection on a rejecter when we have had a thousand hands extended? The loneliest times of my own life could not be salved by anyone. When I weep, drunk and alone, it is nothing you can fix with all the love in the world. I want J. back, and I want my mother, and they aren’t there, and nothing else will do. I would also extend that loneliness is an exquisite and important rite of passage. Like my romanticizing of the cloche lady in the Hopper, abandonment is a state of mind that we need to address and come to terms with. The theme in pop and country songs about being left lonely, left behind, left out, are crucial and integral to our personal evolution. In high school, I didn’t know that every high school kid was lonely. Yes, as a bullied kid, I was probably more lonely than some. But as a kid who had found a way into the realm of imagination and creativity, I was probably well ahead of the rest in finding sanctuary. Just as today’s studies tell us about lonely science, we’ve known for some time that churchgoers and other spiritually grounded folks have better mental health. This is attributed to more connectivity. But that hive of community is one of the reasons I’ve avoided my spiritual matters in public life. I prefer to read poetry and the bible at home, and I commune with theologians and writers this way. I don’t want to see a bunch of people on Sunday mornings! I feel fragile and invaded after good-intentioned folks at my sister’s church fall over the pews to shake my hand and say “nice to see you come out” when they don’t know anything about me. Still, study after study after study has confirmed that religion is apparently good for your health and the reason is connection to a community. Here, ever contrarian, I wonder. Is it really the connection to other lost and seeking humans over triangle tuna sandwiches that makes the difference- or is it connection to God? The famous David Caspar Friedrich painting about the monk on the shore comes up in various Google searches for loneliness- self-portrait, lonely monk, desolate, empty. But like Jane waiting for no one in the automat, I see the work as a triumph. The monk is solitary against the wild, but he is intimately connected with the cosmos. I never see this painting as a lonely one. I’m not so sure the artist did, either. Whether God is true or false, it’s scientific to say believers are ahead of the game. The interpreters of science leap in and conclude it’s the connection to community. Some of the first studies in sociology showed that active goers to synagogue and church committed suicide the least, and their lack of loneliness was cited as the reason. Perhaps many find joy through the hubbub of hellos, but I grow furious when someone who doesn’t know me and doesn’t really give a damn asks how I am and how my holiday was. It’s okay to just exist side by side and not pretend. I wonder if it’s not the social aspect but the sense of meaning that gives the religious their edge. Maybe it’s the perception of relationship to God, not to everyone else. Maybe it’s the feeling that it’s not all futile. After all, people who go to casinos and pubs a lot are also around a lot of people, and this connection is not heralded as a lifesaver. Don’t get me wrong. I understand that Christ said, Love thy neighbour. And I am not suggesting we should harbour rancour to others. I am not advocating cruelty, and I am not saying we should always leave everyone alone. I am not saying everyone has my kind of loneliness, or lack thereof, or any of the other things some will try to read into my words. I am only saying that superficial empathy and companionship are quick fixes that don’t hold for many of us. I am only saying that constantly giving love to those who haven’t earned it has been the undoing of many souls. I am only saying that for some, being around people does not cure their loneliness but creates it. My most dark, profound, naked, terrible, disappointed moments are with other people. In all the days that I kept hoping you would fix it, I remained impotent. When I stopped asking you to love me beyond what you could and did, when I stopped asking the dead to rise, the unable to reign, I found a fragile peace. When I realized that fewer and deeper friendships with those whose trust I earned and mine theirs, I stopped giving myself away so easily. When I realized that you don’t go to church or to art receptions or to school to be seen or to make idle chit chat, but to nourish the soul with connection to something more important than superficial bonds, I started to find what I was looking for. Since I have learned to sit in cafes by myself just like Jane and say no to group excursions to movies and go by myself, since I have said no to roommates and no to relationships with men just for their own sake and no to going out on Friday nights unless I want to, I have been far less lonely. Not forcing myself to hold up the social above all else has actually made me far more generous to the needs of others. Not spending time on people just because I’m supposed to has freed me to spend more time with the people I care about most and grow closer to my family, to give what I should to my closest friends, instead of spreading myself thin in the lunch room or on the subway. I am able to truly enjoy meeting people and being with them since I found the peace of mind to be alone when I need to be. Far be it for me to question scientists and doctors and the New York Times. But I think Thomas Moore nailed it in his wonderful book Soul Mates. “…We may think we're lonely because we have no friends,” he writes, “when the fact is we have no relationship to ourselves.” Lorette C. Luzajic Lorette C. Luzajic is an artist and writer living in Toronto, Canada. She writes about art, and makes multilayered collage paintings that incorporate text and literary themes. She has published hundreds of poems, short stories, and creative essays. Visit her at www.mixedupmedia.ca.

1 Comment

Scott H.

3/7/2016 06:55:06 pm

The loneliness article was wonderful. Another Jane (Jacobs) once said that privacy was the greatest advantage of living in a city.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|