|

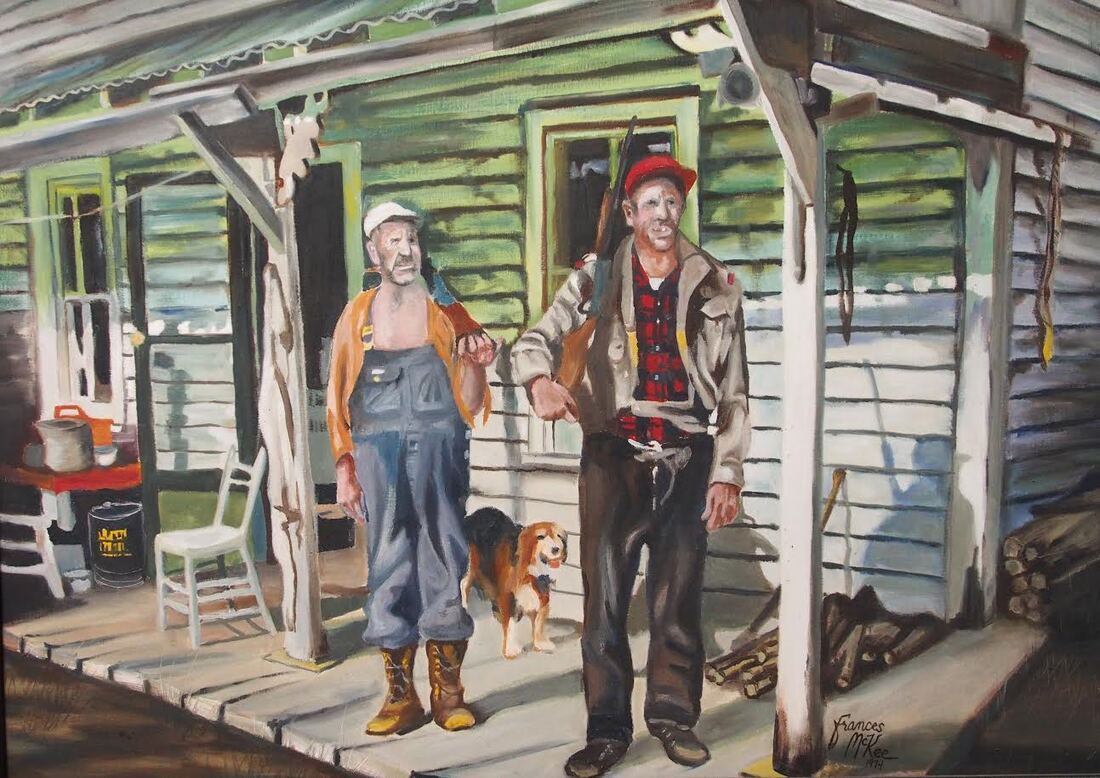

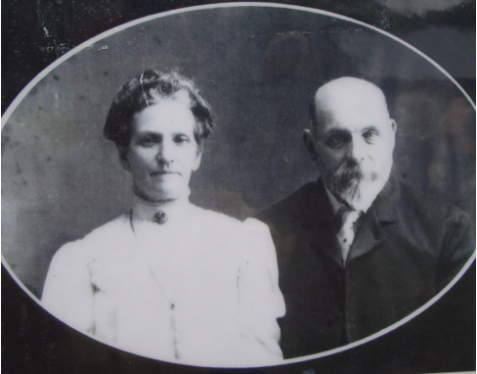

I found the painting in a cousin’s basement in my home town, Elmira, Ontario, Canada—two old geezers with guns. The taller one had obviously tied his pants up with a cord. Their place looked more like a shack than a proper home. Had they just returned from hunting or were they hillbillies keeping intruders away? Searching for details of the lives of our ancestors involves real detective work. Most databases can only give you names, dates, and places—no real stories. On my first visit to Hastings County, Ontario, in June 2014, Edith McCaw, a local historian in Coe Hill, Ontario, gave me the names and telephone number of a couple of elderly “Irish brothers.” She told me they just might know the whereabouts of the former McKee property. I mentioned the Irish brothers to cousin Kenneth, a sixth-generation co-owner of the pioneer McKee family farm in Wellington County, Southern Ontario, and he remembered a painting that used to hang in our Uncle Gerald’s house in Elmira. My sister Frances (McKee) Gregory had painted it from a photograph Gerald had taken on a hunting trip in the early 1960s—a 25th wedding anniversary present from the family. Gerald, my dad, and most of their brothers, loved blood sports. In July 2016, I returned to Ontario from my home in Albuquerque, New Mexico, to further investigate the early life and times of my paternal great-grandparents, John and Mary Jane McKee. Although the first-born son, he had left the family farm in Wellington County, which was established by his father, my great-great grandfather, William McKee, and his father Thomas—immigrants from Glasgow, Scotland who arrived in the 1840s. In the mid-1870s, John and Mary Jane married and settled in Hastings County—wilder country to the east, directly north of Belleville, Ontario. I wanted to discover more on what kind of people they were. I had heard stories that they were religious and believed in primary education—they had helped to build a church and school in their new community. But I hoped to learn more about their attitude toward guns. Unlike my father and his brothers, I had no use for firearms since the day I killed two deer when I was around 16 years old. I had discovered stories that my ancestors owned two old muzzle-loading muskets, but they were missing from William McKee’s last will and testament. I wondered if his son John had brought them with him to Hastings County. My great-grandparents didn’t leave a tidy trail to follow. During the earlier visit, I had turned up a few clues, but when I stopped to take photos or knock on doors for information, swarms of mosquitoes attacked me. This second visit in late July, I accurately calculated, would be less tortuous, for mosquito populations usually decrease by then. According to family stories, John and Mary Jane McKee had put down roots in “Rose Island.” On the earlier visit, in Coe’s Hill library I found a short history of the place in a book titled The Loon Calls. It stated that Mary Jane had named the settlement, but I couldn’t find any islands on maps of the area, and if wild roses once grew in this wilderness, they were no longer evident. I couldn’t help but think that Mary Jane had chosen the name “tongue in cheek.” To me it didn’t seem rosy at all. John and Mary Jane were latecomers to the settlement process in Hastings County. They had to be satisfied with available land lots about 86 miles (140 kilometers) north of Belleville—bushland with a thin layer of soil covering the rock of the Canadian Shield, which had been scraped clean by glaciers during the last Ice Age. In the late 1800s, free grants of 100 acres (40 hectares) were offered to anyone willing to build a house and to keep a minimum of 12 acres (five hectares) under cultivation for five years. I knew from my previous visit that no lots were marked, so their former property was hard to find. With copies of the photo of my sister’s painting in hand, I drove to Madoc, Ontario, to meet Delbert Irish, age 89, a well-known local whittler, and his elder brother Leslie. I had called them to make an appointment and to be sure I’d be welcomed. When I arrived, Delbert was whittling one of his pieces for sale, but he put down his tools and his brother joined us. I showed them the photo and asked, “Do you know these guys?” Delbert replied, “Why that’s Uncle Raymond and Uncle George. Where’d you find this?” I explained the origin of the painting and asked, “Is this at Rose Island?” “Sure is,” Lesley replied. “That’s at the old Irish property.” “They both have shotguns, looks like. Did they keep those for safety in that wilderness?” I asked. Delbert said, “Those are rifles, not shotguns. Our uncles loved to hunt deer and so did we. There’s a lot of deer in that area, still today.” The photo of the painting set off a long discussion about Rose Island, during which I discovered that in the 1930s, Delbert and Leslie with their parents had lived on the former McKee property after the McKees had sold out and left. They told me people still called it the “McKee place” at the time, 20 years after my ancestors had departed. The Irish brothers were most helpful in describing what to look for along Rose Island Road in order to locate the place. From Madoc I drove to Coe Hill, where my ancestors had shopped for provisions and caught the train. I stopped for lunch and bought a T-shirt and baseball cap printed with the words “Coe Hill Billy,” then I headed west on Rose Island Road, a narrow track through the bush. The Loon Calls mentions that John McKee served as postmaster at Rose Island for 25 years. I knew from family stories that he also operated a sawmill and a gristmill. He milled grain for his family, their livestock, and the community. As I drove down the gravel road toward Rose Island, I felt totally alone. I could see no sign of people—no ongoing farming or other economic activities. In places, I saw the remnants of old cedar fences, but no farm animals to enclose. I went past a deserted-looking house on the north side of the road and a broken-down barn with a few old sheds on the south side. The buildings looked like the “McKee place” the Irish brothers had described, but I wasn’t sure so I drove on. It seemed too far from other houses. I finally came to few other houses and small farms, and after crossing the Hastings-Peterborough county line, I saw an old man with a long white beard repairing a hay mower—the first person I had seen on any property. When I drove up the lane, I could see that his face looked younger than I had anticipated. As it turned out, he was Jim Eadie, a farmer who had recently retired from a career as a forensic expert with the Ontario Provincial Police. We engaged in a good conversation on living in the US versus Canada—especially concerning America’s free-wheeling attitudes and lack of laws on guns. He told me that one time he was loaned to the Los Angeles Police Department to help solve the O. J. Simpson murder case. But now, incongruently, he raises sheep. I asked him, “Did you ever hear of the name McKee around here? They used to have a farm and ran the post office.” “Can’t say that I’ve ever heard that name. But you might ask Merle Post in the second house to the left after you cross back over the county line.” He told me he had done a little investigating around the abandoned buildings I had seen on my way in. We discussed the possibility that a sawmill and gristmill had once been there because the place had a water source. I thanked my new forensic expert cum sheep farmer acquaintance and drove to Merle Post’s place. The name “Post” rang a bell. I had read in The Loon Calls that a John Post had been the second person to take over the Post Office—a vocation well suited to his surname—after the McKees left Rose Island. As it turned out, Merle Post knew nothing about a McKee family, but she gave me the number of Mac Wilson in Coe Hill, who had once owned the abandoned farm I’d seen. I was getting a little “warmer” in this search. I returned to the broken-down buildings to investigate. I knocked on the door of the small house on the north side, probably built in the 1940s or 1950s, but no one answered. I walked around to the back and saw something strange—the remains of an old log foundation. I could see that the logs had been partially charred and recalled what the Irish brothers told me, “The McKee place was a big two-story, frame house—kind of T-shaped. But it burned down some years ago.” I had found what I was looking for. Straight back from the house I spotted a small lake—more like a swamp full of old stumps attracting mid-summer frogs and insects. A creek ran from the swamp down alongside the house and under a bridge to the other side of the road—a perfect location for water-powered mills. The old barn beside it had a stone foundation much like that on the McKee home farm. It was built quite high, obviously good for protection against spring floods. The barn appeared to have been built or rebuilt in the mid-1900s. I walked back to the house and used my cell phone to dial the number given to me by Merle Post. Mrs. Wilson answered and passed the phone to her husband, Mac. I told him about my mission and where I was standing.

Mac spoke in an enthusiastic and helpful way. “Yes,” he told me, “I owned Lot 30 on Rose Island Road from 1956 to 1972 where the McKee place was. I also owned Lots 31 and 32, which they owned as well. The large house had burned down by then. I purchased the lots from Jerome Campbell, who built the smaller house sometime in the early 50s. I worked the farm there until I retired. Had to close down due to losses.” “What kind of losses?” I asked. “Cattle rustlers, actually.” “In Ontario?” “Yep. You could find thieves anywhere those days.” “Did you have to guard your place with guns?” I asked. Mac laughed, “Nope. We had guns for hunting but let the police deal with thieves.” “Were there any police stationed in Rose Island when my great-grandparents lived here?” Mac paused and then replied, “I doubt it. But it must have been a pretty wild place, even wilder than when we lived there. There’s no real record.” Then I asked, “What about the creek? Did you see any traces of an old mill there?” What he told me was music to my ears. “No, but I recall some stories that the McKees ran their mills with a big waterwheel. They had a gristmill and a sawmill.” “Did you see any sign of a mill powered by a steam engine? The water from the creek wouldn’t power a mill year-round.” “Can’t say I saw anything like that,” Mac said. I was testing a theory. The husband of the helpful local historian in Coe Hill had suggested this possibility on my earlier visit, and it made sense to me because my grandfather Alexander, and his older brother, Harvey, had both become steam locomotive engineers after they left this place. How else could they have learned how to run such technology in the wilderness? After I thanked Mac Wilson and ended our conversation, I stood there staring at the old foundation. During the years they had lived here, my great-grandparents carried on the farm family tradition of populating the land, bringing eight children into the world—four girls and four boys, including my grandfather, born in 1887. Along with operating Rose Island Post Office, John and Mary Jane McKee also earned an income from selling groceries, hardware, and fuel. Most likely Mary Jane and their older daughters looked after the store and post office, while the sons helped their father with running the sawmill and gristmill, clearing, ploughing, and cultivating the land. As it turned out, the land on which my great-grandparents had settled did not match their fecundity. The thin soil required years of lying fallow between crops in order to be productive. In addition, the Coe Hill area did not remain prosperous. An iron mine near town closed in 1885 because the ore contained too much sulphur. None of John and Mary Jane’s children had any interest in carrying on in this desolate place. In 1910, after 35 years of toil and sweat, they decided to sell their land and move back to the McKee family farm in Wellington County, buying it from John’s two younger squabbling bachelor brothers. Eventually, many of the other families who settled along Rose Island Road also sold out and left. The forest advanced and erased most signs of those better times. I could imagine John and Mary Jane packing their belongings, including the old muskets that were missing from his father William’s will, and putting them on the train. The powder horn used to charge those firearms had William’s name etched on it. Probably William thought his son John could make more use of the old guns in this wilder country. Or had there been a disagreement about the need for guns at all? This was pure speculation on my part, as I searched for reasons why John had given up his chance to take over the McKee family farm as a younger man, being the first-born son. I left the ruins of the “McKee place” and drove eastward away from Rose Island. I entered a more forested area where the bush almost enveloped the road. Suddenly, a deer rushed out of the woods from one side and dashed into the undergrowth on the other. As I applied the brakes, I remembered what my father had told me on my one and only deer hunt in November 1961, “Just down the road is the place where your great-grandfather John had a store and post office.” I realized I had been here before. Just like the deer that leapt from the bush, his words darted out of the deep recesses of my memory and images of that day flooded into my mind: For my first deer hunt, a boy not quite 16, my father loaned me his old Lee-Enfield .303 rifle. Stationed on a rock in the middle of a field—so quiet, just a sprinkling of snow on the ground—baying hounds awoke me from a daydream. I surveyed the far hillside, saw a deer, aimed, and squeezed the trigger. The animal flinched and then took off. I thought I had missed, but joining Uncle Gerald and the hounds, we followed a dark red trail—so easy to find the doe. Celebrations followed at lunchtime for that first kill of the season: a toast with sweet red wine, laughter, slaps on my back, my father so proud of me. But all seemed much too easy, with four more days to go. In the afternoon we resumed the hunt. A cold wind had blown in from the north. I sat on a small hill crowned by rock. Again, hounds broke the silence, bushes rustled, hoofs pounded, a startled young buck darted from the woods, leaping up the slope. I fired as he sprung over me, but I missed and cocked the gun. The bullet jammed, then slid in, I swung and pulled the trigger again. The deer dropped close to me—blood gushing from its throat, sputtering, gurgling. Uncle Archie emerged from the woods to shake my hand; his words muffled by those sounds. My stomach churned and I vomited on the ground while Archie shot it in the head. The woods fell silent as we dragged the carcass out. For me that evening, another toast, more pats on the back. I went out with the gang for the rest of the hunt, but never killed another deer and never fired a gun again. Neill McKee This story is adapted from Neill McKee’s new travel memoir, Guns and Gods in My Genes: A 15,000-mile North American search through four centuries of history, to the Mayflower. Neill McKee is a Canadian creative nonfiction writer based in Albuquerque, New Mexico. https://www.neillmckeeauthor.com/ His first travel memoir, Finding Myself in Borneo, https://www.neillmckeeauthor.com/buy-the-book won a bronze medal in the Independent Publishers Book Awards, 2020, as well as other awards and many 5-star reviews. McKee holds a Bachelor’s Degree, from the University of Calgary and a Master’s Degree in Communication from Florida State University. He worked internationally for 45 years, becoming an expert in the field of communication for social change. He directed and produced a number of award-winning documentary films/videos and multimedia initiatives, and has written numerous articles and books in the field of development communication. During his international career, McKee worked for Canadian University Service Overseas (CUSO); Canada’s International Development Research Centre (IDRC); UNICEF; Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland; Academy for Educational Development and FHI 360, Washington, DC. He worked and lived in Malaysia, Bangladesh, Kenya, Uganda, and Russia for a total of 18 years and traveled to over 80 countries on short-term assignments. In 2015, he settled in New Mexico, using his varied experiences, memories, and imagination in creative writing.

3 Comments

Jeanette Panagapka

11/13/2020 02:36:02 pm

Loved reading this, Neill. I'll look forward to reading the rest.

Reply

John Wilson

12/8/2020 04:54:20 pm

I'm a friend of your friends, Ron and Mary Hunt. I look forward to the release of your book!

Reply

connie Irish

2/5/2021 12:26:46 pm

Hi Neil

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|