|

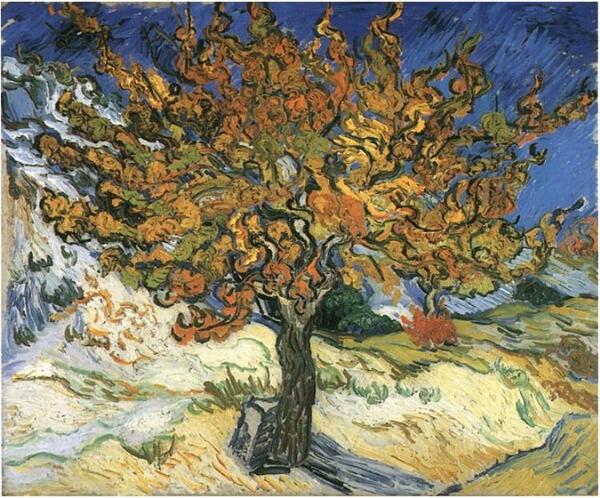

Self Portraits— a Review of Kendall Johnson’s Dear Vincent: a Psychologist Turned Artist Writes Back to Van Gogh (Sasse Museum of Art, 2020) Before I begin, in the interest of disclosure, it should be said that I have known Dr. Kendall Johnson for the better part of 35 years. He is an artist, psychologist, and teacher, as well as my father. It is an honour to have been asked to write a review of his new book, one which I repaid by informing him that I intended to be as impartial and trenchant as necessary. The latter quality was not at all necessary. I highly endorse this book to any consumer of art, though not for the reason that it provides a clinician’s perspective of the works of Van Gogh. I hope this review will clarify what I mean by this, and convince the reader that it is a preferable trait. Electronic in format and unencumbered by the constraints of the press, Dear Vincent makes abundant use of the high resolution images freely disseminated by the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. Each page of text faces, more or less, a corresponding image, curated by Kendall (as he signs his letters, and how I will refer to him). To prepare myself to write this review, I travelled with my family to the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena to view the one painting in this book accessible to a Southern Californian, Van Gogh’s Mulberry Tree (1889). Painted 99 years before the birth of my sister, the canvas is vibrant yet, awash not only in colour, but in thickly-layered texture. The caked-on brush strokes stand out on the canvas (still visible along its margins) like a bronze frieze. Rather than figures leaping out at the viewer, a vortex of texture pulls the image out of its own dimensions. I felt dizzy after watching it. I wondered how a photograph, irrespective of the resolution, could duplicate the experience. A writer and a painter himself, Kendall solves this impasse by creating a book of layers, thickly daubed. The text itself is a series of juxtapositions. On each page the reader meets three distinct blocks of text, with the equivalent number of fonts. The first block gives biographical and interpretive information to segue from the painting to the next block, an excerpt from Van Gogh’s letters. Next, the very conceit of the book, Kendall responds to the letter as though he himself were the recipient. Having identified as a psychologist, Kendall allows us to imagine a therapeutic conversation between himself and the artist. However, these categories do not remain static. The focus shifts from Kendall observing the artist to Kendall taking in the painting, considering himself as an observer, and the text often interposes a final block of text, a short lyrical fragment. These short lyrical passages carry us out of the biographical speculation, returning us to the canvas. Reversing this process, for the sake of this review, I would like to let the author speak for himself. What follows now are excerpts from a conversation I had with Kendall. I have edited them for clarity and length. Q: Under what circumstances did you create this book? A: Gene Sasse, Founder and Director of the Sasse Museum of Art approached me about it. Since the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam had made high resolution images of Van Gogh’s painting publically available, he suggested we put together a virtual exhibit through the Sasse Museum. He approached me specifically from the position of my being an artist and psychologist. I could give commentary from those dual perspectives. Q: He was interested in how Van Gogh’s possible illnesses affected his paintings? A: Yes. Various authors have attributed his work to illnesses ranging from depression, psychosis, addiction, and even problems in seeing. Through my research and writing, I came to believe that the conversations about illness were sidelines. They missed the point. His work excelled in spite of, not because of, his mental illness. He did this all in spite of the burdens he carried. Q: How did you decide what images to include and how to order them? A: Curating the images was my initial task. My first interest was choosing paintings I really liked. My mother and father were both artists in their own ways, and I chose many images I had grown up with as prints on the wall of my childhood house. My favourite painting is actually in the Norton Simon, nearby. The first time I happened upon The Mulberry Tree I was transfixed. Like many of his paintings, it simply pulsates. People were pushing around me to get by, but I couldn’t move. Q: You also chose to curate excerpts from his letters. How did you decide what to include, and how to pair it with a painting? A: I really felt like I was curating his life through his letters. I based the excerpts on my selection of paintings, and chose them because they provided insight into the conditions in which he painted, his motives, or what was going on in his mind at the time. I had selected the images based on my personal preference first, and their significance next. I looked at three elements. First, I wanted to illustrate his personal maturation combining with artistic self development. All of his great paintings are carefully composed with an inner logic. Once he did that, he produced masterpieces. Those were the first two criteria; how was he maturing personally and how did that combine with his own artistic growth? The third element I looked for were his psychological struggles. It’s ironic that I approached this project being asked to give my clinical opinion of those struggles, my professional diagnosis. In fact, in doing the project I came to view those as extraneous factors. But they still played an important role in his work, obviously, but not as causes. Illness, poverty, and social difficulties functioned more like crucibles. Madness did not determine his aesthetic, but provided an impetus, energy, and an urgency for his work. It’s as if he was struggling to say important things before the light was lost. Q: Your text format is unique. When the reader opens the book, they will find each painting on the left side of the page, along with identifying information. On the right, there are three distinct text blocks. The first block gives orienting information, almost like clinical notes on the biographical and psychological context for the painting. The second block is the excerpt from his letters, providing a counterpoint for both the painting and the clinical notes. The excerpts are given in a cursive font, in iron red. Under that, in a third font, we find your notes to Vincent. In this third block, the reader encounters a much more personal engagement with the painting and with Vincent. You sound like a friend, less than a clinician. You compare memories and respond as an artist. How did you settle on this unique text structure? A: Van Gogh was not only one of the more complex artists, but one of the most articulate. Over twelve hundred letters have been found, and many hold literary value, and certainly all give insight into his work and his life. The layers of text reflect the layers of his work, his concerns, his developing style. Some of it is my reaction as a shrink. Others as reactions as an artist. The latter wins out over the process of the book. The drama is in the process of this side of me winning out. I came to see the underlying psychological factors less important the Van Gogh’s accomplishment as an artist. Q: It should be said that there is a third feature of your letters. After your prose response, you often provide an additional layer, which completely collapses the clinical viewpoint. You insert poems beneath the prose of your letters, and many of these poems of identifiable as haikus or tankas. What was your motivation for doing this? A: I love the epistolary form. It’s personal. I don’t have to limit myself to an ostensive position of “objective expert.” Once embarked upon a personal interchange, though, the possibility for perspectives opens up even further. A poetic response allows access to the work at the aesthetic level. Q: So you consider your letters to be prose poems? A: Yes. The virtue of the prose poem is that it allows context with response. The haibun form allows even more. The addition of short form poetry following the prose poem allows a “stepping into” Van Gogh’s world. Combining the context of the prose poems with the imagist haiku and tankas, layers different realities and meanings. When I break into the verse, I’m stepping out of the context, capturing the immediacy of experience. Q: Is it fair to say that the letters and the verse mirror the doubling of the process of juxtaposing the paintings and the writing? A: I think so. My own process as a reader of Vincent is reflected by the process of writing. I emphasize critical factors as a psychologist, I empathize as a person, and finally I commune as an artist. Q: Why specifically did you choose haibun as a method of communion? Why did you choose a Japanese form of prose and tanka? A: Again, haibun fits the epistolary poem form beautifully, allowing contextual factors to be addressed. Haiku is about direct experience. Tanka allows an additional two lines, which give the space for placing the poet in the picture, and for expressing emotion as part of the picture. I see the haiku and tankas as imagist poems. They capture the moment directly, and point beyond. Q: Is it a reference to the influence Japanese prints had on Van Gogh? A: I think so. The circumstances of the block prints embody a cultural hybridity. The block prints Van Gogh and other artists of his time purchased had become available from the newly opening trade with Japan. The emergent middle class in Japan created areas of indulgence for pleasure. Part of that was the production of cheap prints for export that found their way to Paris. They emphasized bold lines, flat planes, and bright colour—all aspects of van Gogh’s work after he left Paris. Some have said that these prints sabotaged the delicacy of impressionist painting. … Reviewing our conversation, my only dissatisfaction was with his response that he chose this epistolary form because it interested him. I think he was too modest. Rather, his fictional epistolary exchange, using as touchstones authentic letters to Theo, mimics the act of engaging an artist and their work. We make meaningful connections based on the information we have at our disposal. The artists are silent and the paucities of their lives, their human smallness, their failed relationships and their quiet deaths, are silent. The paintings do the talking. The boundaries between the viewers and the perceived becomes porous. This book succeeds at performing this experience. Kendall the psychologist becomes Kendall the viewer. The viewer becomes a part of the vision. In the galleries today, the original paintings have lost their vibrancy. Van Gogh’s colours have faded. However, like the layers of colour exerting a centripetal pull in the Mulberry Tree, a force beyond the senses seems to remain. Certainly, when we stand before paintings, we bring our own perspectives. Kendall’s book is an incisive enactment of this ritual. It goes far in showing that in galleries, as in zoos, we think we are the observers; but something thinking, something beyond our own senses, seems to be staring back. Even if you find the Van Gogh market oversaturated by books, speculative theories, kitch of the detachable-ear variety, etc, a book of such uniqueness is a valuable addition to ekphrastic literature. I highly recommend this book, a lifetime in the making. Trevor Losh-Johnson Click here to read the book online. Trevor Josh-Johnson is a writer and educator from the San Gabriel Mountains area. His first book, In Cabazon, was published by BlankSpace Publications in Ontario, Canada, in 2012.

1 Comment

Deb Madden

8/21/2021 09:16:33 am

Magnificent! And I say this, trying to not be biased by the fact that I know both father and son a little bit. I have a personal connection. My mother told me that when I was about six and in the New York Metropolitan Art Museum she saw me frozen and crying in front of Van Gogh’s Jerusalem Artichokes (I think it was). She asked me why I was crying. I told her the person who painted this was so sad. I remember being caught in the tension of the brushstrokes.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|