|

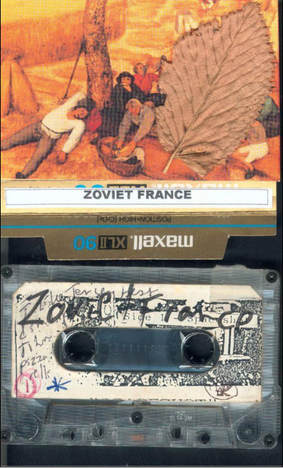

Shouting at the Ground, Through the Trees “A silent man, walking in solitude by a mountain stream… We begin to see what is real and what really deserves our allegiance.” Gary Snyder ☉ Listen to the radio show as you read this: Wreck Zoviet France Shout 1190 Roquette, Pimprenelle, Hirondelle, Lézard des murailles, Muquet de Mai, Bruyère, Patience, Fongère, Sapin, Chataigner, Laurier Franc, Pissenlit, pie-grièche à tête rousse, Guêpier d’Europe, Mauve des Bois, Chauve-souris, Épicéa, Fauvette, Traquet motteux, Marronier d’Inde: repeating any of these French flora or fauna species in any number, in any order overandover will transport you to the place I am about to describe because as we all know, language is the basis of our world, how we perceive it, how we construct it, how we negotiate through it, and, through mantras, transcend walls, borders, and this “blooming buzzing confusion,” as William James described our world. Religious people, monks, gurus, musicians, and poets all know this. Language is the effluvia that allows us to interact, to inspire. And the above is my mantra, my escape clause ... The reason may very well be that this particular album has a long personal history: It has stood by me, has enchanted and provoked me over the years but most eidetically for a long period of self-imposed hermitude in the south of France – and elsewhere. It justifies and endorses the very solitary life that is both sought and endured. I recorded Shouting at the Ground in pre-digital times from vinyl to cassette in the basement studios of WFMU shortly before I moved to France. The magnetic cassette tape I chose was already occupied by other sounds, and yet, I had no moral qualms about recording over it. This was a tactic generally frowned upon by audiophiles and WFMU DJs obsessed with high fidelity. While some people pack a rucksack with an emergency medical kit, a hip flask filled with a liquid of some proof, or a big lunch, I packed mine with cassettes and an apple. I knew my survival would hinge on essential sounds the way others would never forget a canteen or a pocket knife before they set out on a hike. I spent great, long stretches of hermetic time out of Paris, in the South of France, in a stone house on a hill to the east of Albi and just north of Castres and Mazamet – a beautiful area with a view of the Montagnes Noires; there are few tourists, few locals, and a broad selection of great, modest, underrated Languedoc wines and wonderful breads such as the miche, which I describe as made of water, salt and flour in the shape of a baseball catcher’s mitt. Albert, the property’s caretaker, picked me up at the train station in June. His English was limited to a dozen words. My French was a timid stream of nouns and unconjugated verbs. But somehow communication happened: He showed me where everything was: silverware, work gloves, linens, wood for the stove, some basic provisions: bread, cheese, coffee, eggs, wine. How to open the mint-green shutters and windows. There’s no TV, just an old portable radio with a cassette deck. That’ll be my companion for the next 10 to 12 weeks. I am going to write a novel or maybe just fill the endless time barely passing with something that pretended to such a purpose. But also, I just wanted to BE – be away, be somewhere else, be myself in relation to the world and all its attractive and distractive features ... and, I was there to make money as a kind of tree trimmer/lumberjack – and upon further research, discovered I could have been called a land manager too. X’s uncle drove up from Toulouse to make sure I full comprehended the importance of my task. He was a dapper man with a moustache you associate with movies from the 1940s and an aptitude for English he was proud to show off. My days were simple: It was summer, I did not need an alarm; the sun managed daily to part the mist and squeeze through the slatted shutters at just past 5 AM. I would rise, and as I reheated yesterday’s coffee, I might scurry out briefly to touch dew on grass, behold it, and then return to write until 7:30 with equal cups of reheated coffee and cold Ricoré [instant chicory coffee substitute], which was perfect for dunking hunks of my miche brought fresh ever 3 days by Albert on his way to work. [Are the crazy people those who do this kind of thing or are they the ones who never-ever experience this dunking delight in their entire lives?] I made a big breakfast, packed an even bigger lunch, dressed in my holey work pants, high rubber boots, checkered shirt and bandana, checked to make sure I had my citronella oil insect repellent before hiking off to my job along the rusty barbed wire that kept a few grazing sheep [moutons, I repeat overandover] in their part of the pasture, la-la-ing, singing, repeating hypnotic phrases in French – “le tapage des oiseaux ivres de lumière” [The twittering of birds drunk with the sun, Charles Baudelaire] – blowing kisses to the sky, humming, talking to a rabbit or a pheasant – the only thing a spider web has caught this morning is dew – along this magical petit chemin, a path consisting of 2 old tractor ruts that attract many audio and olfactory delights – like how a story line through a novel attracts logic and intrigue. I notice that the telephone poles wear tin caps to prevent them from rotting. Oblivious to how ridiculous this would all seem if viewed on a hidden camera. The permanence of elements – stone walls, like slate, like a stump wearing a green sock of moss, like this old rusty saw attached to an ancient pole, shiny with a hundred years of a hand gripping it – contrast with the floral effluvia or the tufts of early morning mist caught in the grasses, illuminated from a mysterious source as a breeze runs its fingers through the tops of the trees. The brouillard [it’s onomatopoeic, it describes mist in sound] envelopes you in its swaddling layers as it descends into the shad of the valley, leaving behind the stone house. The work [over a summer and then through a good deal of the following winter] was in a beautiful woodland, a tree farm of lumber-bound firs and pines, but to me just a wood of somewhat hypnotically, symmetrically planted evergreens – perhaps 10,000 of them in total. Upon arriving in the wood at 8 AM, I lap on citronelle to neck, head, hair, and arms to keep the gnats away. [This mostly works only if I believe it does]. I put on my work gloves and begin trimming branches up to a height of 6 metres, using 2 tree pruner saws mounted one on the end of a 2-metre wooden pole and the other on a 4-metre pole. I take periodic breaks for a sip of iced water, juice, an apple, some nuts or I might write something down, an observation, a line to a poem never finished, gibberish. “How does one see the thing better when others are absent? Is looking like sucking: the more lookers, the less there is to see?” -Walker Percy As I worked I heard the crackling of branches, my groans and heavy breathing echo through this wooded parcel; my body already steaming from the exertion and its not even 9:30 AM. The saw dust falls from the scythe-shaped saw and sticks to my skin. I am totally alone here. At the end of my workday – 2 PM [before the full heat and full annoyance of gnats] – sawdust covering my head, pine resin drops sticking to the hairs on my arms, I noted how many trees I had trimmed. If I trim 80 trees at 5 francs per tree, I could earn an OK living wage of about $66 a day in the middle of nowhere. From my scratchy notes it looks like I averaged about 95 trees in 5 to 6 hours, or about 1 tree every 3 minutes. I see from my rows of figures in a notepad that on good days I’d finish 149, 145, 131. The harder I worked in the morning, the less hours I’d have to put in and the more time I’d have for living and writing. The pace is sometimes frustrated by resin that builds up on the saw blade. This I have to clean off using rough stones and a cloth soaked in rubbing alcohol. [Back at the house I might use a rag soaked in gasoline]. Then I walked back home – the 40 varieties of flowers along the way mock any hubris we may manufacture – with a plucked bouquet of wild flowers or a pocket full of wild strawberries. I stop to listen to the bees buzzing, the birds chirping [I only look them up many, many years later: Skylark, Common Linnet, Crested Lark, Swift, White Wagtail, Serin, Corn Bunting, Goldfinch and Fan-tailed Warbler]. The running brook: I want to record it and, like Beethoven getting down on his belly to listen to its gurgle, I try to learn its enchanting secrets. The mud sucks up my boot; the mud smells a million years old. Two young lovers holding hands in the distant midday sun, heading to the reservoir to go skinny dipping. I have seen the gleeful and carefree on my days off, lying, white-skinned, on striped towels along the shore. A teenage summer doing nothing is a summer well-spent. One day – maybe it is how like a good frame enhances a painting – the stillness frames the ambient sounds. I hear the cows [vaches] 100 meters off in the pasture slowly chewing, each at peace with her own halo of flies. I find two mouton skulls, parched and bleached; I bring one back to place on my work desk. I run a steamy tub of aromatic water which was – I don’t remember – probably some mix including sage, chamomile, or orange peel, offered as a going-away gift by X whose resentment at my leaving reminds me of the girl in the movie Betty Blue. I kept this observation to myself. [I refuse to even entertain the notion that she is secretly relieved that I am gone]. Probably more than once you could have caught me drinking some of this bathtub tea. I press the PLAY button and Shouting at the Ground begins to waft, to loop through the house as I lay in the bath. I am aware of my body and its constituent parts, by how much each muscle and joint aches. My body has been rearranged by honest work in the thorns and hard brittle twigs crackling to produce a glorious sensation of pain, callouses, blisters, cuts, and scratches – I am in good shape but I hurt. Shouting is looping as I eat a lunch of local cheese, hunks of miche, a salad of greens grown out back, or omelette, artichaux, avocado salade, cup of coffee, while fiddling with the radio dial to listen to human voices discuss issues on Radio France. I return to Shouting; it loops and drones as I climb back up the stairs, as I take my chair, as I begin to write, sitting in the blazing sun at a desk with a view of the Montagnes Noires in the distance. The ritual-routine is: Wake, work, bathe, eat, listen, write. Invariably, and perhaps a thousand times during my 10 weeks of hermetic non-contact with other humans, I would press this tape into its carriage, press PLAY and set it to auto-reverse on this old padded-casing cassette deck and AM-FM-Shortwave radio [bent antenna] and just stare. I was indeed creating auto-reverse loops of loops, reimagining the orbits of the universe and the orbits of our preoccupations simultaneously. Most of Zoviet France’s compositions hinge on pre-digital looping techniques [which gives them a palpable organic-mechanical feel]. Loops are closed circuits, are rings, are halos, are lifesavers that continue on into eternity unless you switch them off at bedtime or a lightning storm causes an outage. Music is based on repeated patterns, rhythms as prescribed sets of notes repeated, rhythmic repetitions. Music and the things music makes us do like dance, dream, enjoy the moment, are hot-wired into the deepest of natural processes. Nature is a series of circuits, the seasons, perennials, precipitation, making the audio loop an analogous ecosystem of sorts. And these loops are Zoviet France’s way of making a certain sense of all these cycles.

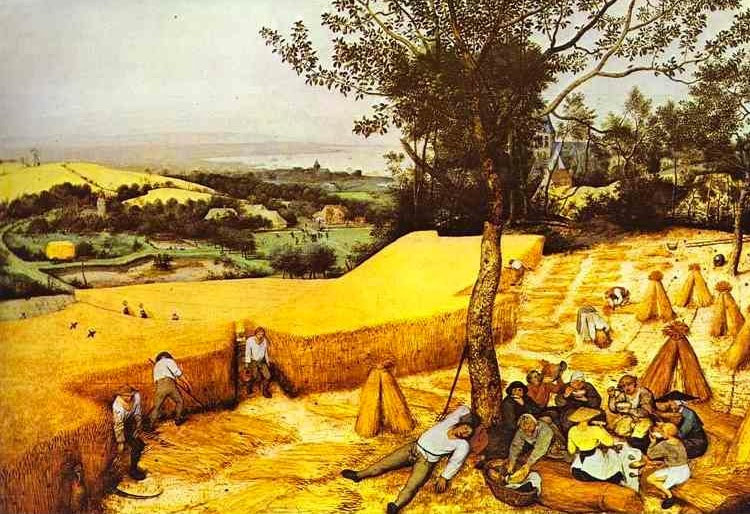

The early tracks send me [I hope you too] off on a surreal, lightheaded walkabout with unsure footing down a long, dimly lit path serenaded by exotic instrumentation and flautists as anonymous as the wind. “Smocking Erde” has its lurking and heavy-sighing-among-trees vibe; “Palace Of Ignitions” with its mesmerizingly open plucked strings that act like a geo-psychological reconnaissance device, while “Come To The Edge” represents a pure, organic loop that places you in the realm of maybe a lesser-known Monet, lost in the mesmerizing sweep of the outdoors and various fleeting, disconnected snatches of mysterious audio blossoms. Albert, a solitary man with cheeks urged red by the sun and wind, and a stoop that forebodes our lot as we head toward dust and worm, delivers a huge miche, a bottle of vin rouge that he holds up over his head in his earthen hand, a basket of potatoes and tomatoes from his own garden. He tells me this house was burned down during WW2 by the enemy, having served as a strategic outpost for the Resistance – it’s all about the view in both war and peace. I tell him the howling wind, the clattering of a loose shutter, and thunder kept me awake last night. I don’t tell him I kept dreaming about cars full of hoodlums pulling up outside because I couldn’t figure out how to phrase it in French. He brings me to the west side of the house; he shows me the shale shingle wall that protects against lightning strikes. Chauves souris [bats] live under the shingles – Je les ai vus – he smiles as he shows me. [I first translated “chauves souris” as “hot smile” but that, of course, was wrong]. They come out at dusk. Je sais. Hundreds. Je sais. Bats are mostly our friends because they eat mosquitoes and gnats. Some eat more than a thousand insects per hour! And with that fact and a flip of his beret, he departs. I doze off, awaken in the sun out back and, in a squint, I see a green lizard nuzzled in my solar plexus. I laugh and the laughter seems to be coming from a foreign body – not me. I notice the dark splotches of mosquitoes smashed against the white wall; they remind me of the eyes of some women in Paris cafés late at night. Some tracks on Shouting escort us into a world out of tune, a world devastated by industrial forces and their exuberant magnates... While the atmospheric pipes and flutes on “Dybbuk” help realign us with our surroundings. I might be in a hypnagogic state now, somewhere between reverie, exhaustion, a pastis [yes, why not], and the lightheaded effects you feel just before an electrical storm. Shouting has a bit of an idyll-invaded-by-industry dialectic, of jarring misalignments and dissonance [“Stoke Blauwers,” “Fickle Whistle,” “Carole The Breedbate”] in a world upside down, which then, just as suddenly, shifts and sways to audio antidotes [“Marrch Dynamic”] to disharmony and then pretty much grounds you up and casts you to the ethereal winds [“Wind Thief”]. My self-imposed solitude meant I saw other humans only once or twice a week briefly: Albert and then my weekly trip in the old white Peugeot 505 station wagon to greet the smirky, bright-eyed cashier whose check-out line I would always choose in the local supermarket. I would cherish that lovely smile for the following week. Or there were the wine givers, adjacent to the boulangerie, a couple who seemed to inhabit a dark cave or had once modeled for a Millet painting. They magically tapped vin rouge ordinaire from a wall spigot into heavy liter bottles with saved corks. They insist you take a glass from a ledge and toast the fetid basement air and I will compliment her and I will thank her. I did not bring music with me on my promenades [no Walkman] but “Shamany Enfluence,” serving as Shouting’s sprawling, epic looping, immersive and Buddhist monk-like, ethno-ambient chanting and moaning centerpiece gives you the sensation that you are indeed sweeping across the primordial topography on a sort of magic cloud. It served me well as remembered soundtrack, enhancing my interactions with, and my wanderings into, these strange surroundings, these deep gazing people who have had their feet on and in the earth around here for a very long time. The organic loops are drawn like buckets of water, right from the earth and, yes, I daily drink deep well water, cold even in July – the music, the water. When it rains I work or maybe I don’t. My raincoat is fit for a cinematic phantom that one day spooks a lost dog. I drink the rain water that flows down my face as I pick murs [raspberries] and watch an old lady hobble by – where does she come from; where does she go? – bent in half, no more than 3 feet high, with her knobby walking stick and laced-up boots to support her ankles. The final track [“The Death of Trees”] offers you an audio corollary to some spectral viewpoint – you simultaneously feel depth as if indeed the sound is outlining some hidden cul de sac. Call it enchantment or meditation or a smelting of self, of dreams, of location and sound so that the mind is released from all grief and distraction. Many of the album’s tracks are perhaps about negotiating a landscape, attempts at engaging our earth, which is hindered by the collateral damage we know as “progress.” It’s not as if Zoviet France’s analogue, pre-computer collaging is program music but they do seem to be tinkering with a visceral narrative, a poetic dialectic between nature and man, which, although Zoviet France was thoroughly groundbreaking, was also a central fixation of Romantic-era musicians and artists: how humans with their emerging self-awareness fit into the grander scheme of nature. We think: Beethoven, Berlioz, Grieg and Mahler; Strauss claiming that music can describe anything, even a teaspoon. But there are also many Zoviet France contemporaries I will not now name. I will instead pick up the young toad and carry it out of harm’s way, placing it on the shoulder of the path, shoving it along into the brush. All of these efforts gather at gestures of mimesis and mnemonics: the smell of wood, burning wood, the landscape folding into memory, my muscles strained to their limits, the act of writing, the birds, the weeds and their bursts of effluvia, the scent of sweat + citronelle + resin, the texture of the bread, the complexity of my joy with the simplicity of the cashier’s smile – of greengreengreen in every direction but up. This leads me back to my desk, the writing, the fat notebook; I manage to finish the first draft of my novel, which will eventually become BEER MYSTIC. I now invariably also associate this album with this accomplishment, but also the hikes around the barrage and reservoir, the meadow sloping away from the house, the smell of the wine cork, moisture jiggling on blades of grass, creme fraiche with framboises from the garden, playing rounds of reussite [solitaire] while listening to France Culture 93.2 FM discussions about the effects of extreme surprise on the body or the effects of loud rock music on the performances of professional athletes, as I watch the lizard’s detached tail wiggle on the wood floor for half a minute as the color of the sunset blazes, prisms through the wine bottle, a toast to its glory with an evening pastis, fire flies the size of planets, the bats darting through a dusk brimming with the calls of cicadas and toads, swifts and swooping swallows. Do I care to interview the members of Zoviet France? I’ve thought about it; probably wouldn’t mind. I am interested in what they have to say, but for the purposes of maintaining the sanctity and integrity of the music loose from any framing of it in terms of strategy, reviews, or the artist’s aesthetic intentions, it is probably better to know less specifics than more. Never mind the peril of reading an interview with a musician you respect only to discover too much about him or her, leaving you disappointed and the music forever tainted. To be honest, I am more interested in dissecting how the elements of chance fell into place so that my destination plus the music I brought along, plus my ambitions and situation helped to create this magical moment in time with serendipity as the guest conductor. Despite being one of the most compelling entities to emerge from England’s fecund 80s post-industrial scene, Zoviet France remain a largely unheard “band.” And it is in uncertainty that myth and legend are fostered. I prefer mythical to overrated or overplayed or over-cited – enough of crediting the Velvet Underground with starting EVERY trend and fashion since 1966. Zoviet France’s work may be hard to track down, impossible to find in stores, but you can listen to much of their back catalogue on Youtube – so, no excuses. The reason they are there even if you do not notice is that Zoviet France evades the classic capitalist symptoms and marketing strategies of popular music by forcing issues about what music is or should be and they pay the price – or reap the benefits. This elusive round-robin, idiosyncratic collective of sound-shifters, post-ethnic-industrialists, dronologists, and pata-ethnomusicologists, based in the Newcastle area in northeast England is known as :Zoviet*France: but also Zoviet France, :$OVIET:FRANCE:, Soviet France, and :Zoviet-France and has included, among others, co-founder Ben Ponton, Mark Warren [Penumbra] and periodic collaborators such as Neil Ramshaw, Peter Jensen, Robin Storey [Rapoon], Lisa Hale, and Mark Spybey [Dead Voices on Air]. They’ve recorded countless hours of improvisations, splicings, edits, cut’n’pastes, manipulations and many of this on analogue equipment [pre-sound-software], which is key to their unique organic sound, which reeks of wood and dirt. I may even convince you that you are witnessing the evening rites of a tribe lost in our cultural ADHD-induced amnesia. Anyway, it is always eerily, beautifully “other,” hauntingly enchanting like the soundtrack to an unreleased moral mystery-thriller directed by Eric Rohmer or a meditation on nature by Werner Herzog. After dinner, the sun doesn’t seem to want to set as I watched my friends the green lizards scurry after flies. The bats and swallows are also my friends. The surrounding sound, a sharp, tinny buzz in the dusky woods is not a chain saw but the sound of a million insects rubbing their wings in unison. By the end of the summer, my work gloves have formed to the fit of my clenched hands and the sweat, sawdust and resin have left them stiff; they stand upright on the kitchen table like plaster casts and that is how I leave them – as if to say “hello” or “give me your hand.” As much as we may try to adjust to a location, become an actor in a place that has seemingly accepted or tolerated you, you will forever just be an interloper here, walking barefoot on moss one day and broken glass on pavement the next, an intruder everywhere. bart plantenga bart plantenga is the author of the novels Beer Mystic & Ocean GroOve, the short story collection Wiggling Wishbone, the novella Spermatagonia: The Isle of Man & the wander memoirs: Paris Scratch and NY Sin Phoney in Face Flat Minor. Sensitive Skin is hosting 6 short movies illustrating stories from these 2 books. His books Yodel-Ay-Ee-Oooo: The Secret History of Yodeling Around the World & Yodel in HiFi plus the CD Rough Guide to Yodel have created the misunderstanding that he is one of the world’s foremost yodel experts. He recently finished the Amsterdam-Brooklyn novel Radio Activity Kills with his daughter, Paloma. He is also a DJ & has produced Wreck This Mess, in NYC, Paris & now Amsterdam since 1986. He lives in Amsterdam.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|