|

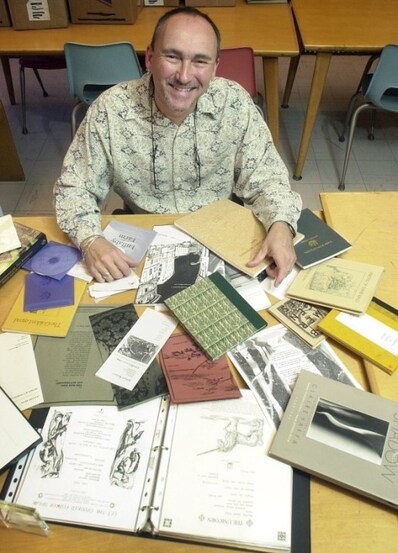

The Ekphrastic Review Interviews Poet Jeffery Beam

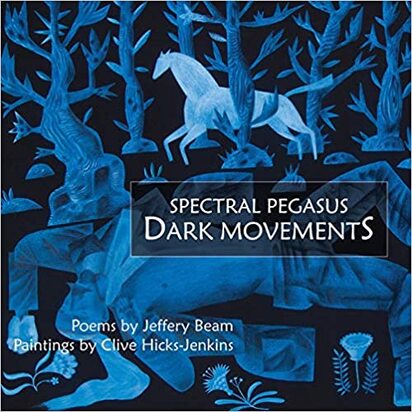

TER: Tell us what inspired your ekphrastic book, Spectral Pegasus/ Dark Movements, in collaboration with artist Clive Hicks-Jenkins? How did the project ignite in mind, and what brought it to fruition? Jeffery Beam: Welsh painter Clive Hicks-Jenkins and I were introduced, virtually, by a mutual friend, novelist and poet Marly Youmans. Clive has contributed phenomenal art for a number of Marly’s books. Many poets have been drawn to Clive’s work and there is even an anthology of poets’ responses, including work by Marly. She was convinced that Clive and I should work together. We committed fairly quickly in November 2014 to work on a project Beastly Passions, paintings and poems which would take as their theme, in Clive’s words, “the darker, Penny Dreadful realms of Staffordshire pottery groups, in which unspeakable doings such as murders by brutes and savagings at the sharp-ends of escaped menagerie beasts, were commemorated in naive imagery straight from the world of the Regency toy theatre.” One image and poem were completed. At that time Clive was engaged on other projects too, one involving a dancer in New York, Jordan Morley. Suddenly the Jordan project morphed into a re-visit to an earlier theme entitled The Mare’s Tale (2000-2001) which had manifested as a group of quite large monochromatic black, blue, and gray conté drawings. The new series of paintings were to embrace the same theme as the earlier series, but with a difference. Both painting groups have at their foundation an ancient Welsh New Year’s mumming or wassailing tradition involving a spectral mare, the Mari Lwyd (a person costumed traditionally with a real operative horse’s skull, a white shroud, ribbons and bells), accompanied by a band of the walking dead. Clive had discovered when his father Trevor was dying in 1999 that he had been terrified of the Mari Lwyd his whole life, and was being visited by her in his death throes. In 2000, Clive began to draw his grief. The Mare’s Tale is shocking, terrifying, and powerfully moving, incarnating Trevor’s end days employing the characters of Trevor, a young man I interpret both as a young Trevor and Clive, and the Mari in her age-old trappings intensified into the macabre. But in some sense the grief and terror remain untransformed in the end. In the new series, Dark Movements, Clive explores and expresses a more transformative, and quite colourful, outcome. Clive has a blog Artlog: views from the artist's studio on which his followers can witness and comment on the creation of his works from concept to finished art. As soon as I saw the first postings about Dark Movements I became entranced. The subject called to me, summoning the death of my own father, and my long-time interests in the Hero’s Journey, shamanism, nature spirits, and Death and Resurrection. And too, the trauma and losses of the AIDS epidemic. This also impacted Clive’s imagination, as well as the death of a very close friend of he and his father’s, poet Catriona Urquhart, who passed, too young, not long after Trevor, and who had collaborated with Clive on The Mare’s Tale. Clive welcomed me to the project, as did his audience once it became apparent that we were collaborating. Clive was definitely the fulcrum of Dark Movements, but was amazingly open to the interactive flow of dialogue through the blog. I like to say that there were really six collaborators: Clive, myself, the dancer Jordan Morley; but also friend Marly, Sarah Parvin – a brilliant, smartly perceptive and wise British art blogger and a trained Jungian (who ended up contributing a major essay to the book), and blog follower Maria Maestre in Spain, who all contributed observations that set either Clive or myself, and oftentimes both of us in other directions. Add to that the writers of the two exhibition reviewers whose pieces are reprinted in the book, Mary Ann Constantine and Claire Pickard, and Trevor and the Mari Lwyd and you have ten collaborators. Ultimately I added music to some of the poems. For example, the painting and poem "Pale Horse" became a ballad in the form of a traditional old English/Scottish/Celtic ballad which led to my working with folk singer and song writer Mary Rocap in North Carolina, and recording that song and the whole group of poems for the accompanying CD. Thus Hubert Deans of Snow Hill Music, CD designer F. J Ventre, and Jackie Helvey who designed my new website, became participants also. And then there is Joy Mlozanowski of Kin Press, my publisher. This is her first published book and her first book design, and as you have seen, it is incredibly beautiful. Gorgeous is not too strong a word. The Joseph Campbell Foundation gave permission to reprint an important quote from Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces; British novelist Lindsay Clarke granted permission to reprint an equally important quote from his novel The Water Theatre. These are essential to the book, in my opinion. I owe so much to Jungian expert Dr. Susan Rowland, and poets Joseph Bathanti, Damian Walford Davies, and Kent Johnson for the extraordinary blurbs they contributed for the cover. We should count my husband Stanley who “tended” me and the Mari and helped me construct a Mari Lwyd to use at readings (you can purchase a kit from trac: Music Traditions Wales), Clive’s husband Peter who “tended” him, and the two friends Dennis and Steven who played the role of the Mari at readings. My sister-in-law Trish passed away in October 2018 and left me some funds to pay for the CD production. We are up to twenty-six collaborators, not to mention all the bookstores, libraries, museums, and art galleries that have sponsored readings. We have a Pegasus Village! TER: Throughout your body of work, the dominant themes that recur and intersect are ecology and nature as spirits or spirituality, gay male sexuality, and the arts. For those of us not well versed on esoteric philosophies, can you break this down in a simple way to explain what drives your creativity and ideas? Jeffery Beam: As a child, as young as three, I frequently experienced visions rooted in the natural world and resonant with spiritual meaning. I grew up in the 1950s and 60s in a semi-rural area of the largest industrial town in North Carolina, within circumstances that were quite dysfunctional but also abundant with soul sustenance. For example, to escape the dysfunction I spent hours wandering the fields and woods communicating with the spirits I found there, but also hours reading folktales and mythology, and secluded in prolonged interludes in my own world of imaginative splendour. I learned to wait and listen, dream and create. My mother had the “Sight” as we called it in our Scots-Irish background, and she was also very strictly “letter-of-the-law” Methodist. My paternal grandmother was my best friend and somehow, unschooled as she was, recognized my poetic being and spent time with me gardening, cooking, and singing hymns. The grandmother of a playmate was steeped in the stories and legends of the Old World and spent hours telling the neighbourhood children tales of the supernatural and the Spirit World. These three women conveyed to me the transcendent nature of the material world in a way that my own visionary experiences were acknowledged as not only natural, but vital, essential, and welcome. However, as they were also grounded, no-nonsense women, they also instilled in me a mindfulness of the ordinary and the necessity to receive such communications with humility, recognizing the contradictory character of their uniqueness, but also that being a recipient did not place me above anyone or anything. I began writing poetry around the age of 14 and was significantly encouraged by my teachers, although before that I was already making visual art and singing. The clairvoyant aspect of my character and surroundings, and my being what was then called “sissy,” amplified and enriched my sense of outsiderness. As a result, I felt much more safe, content, and free in the preternatural world. At an extraordinarily young age I recognized my queerness although I had no name for it. So my private world and my time in the natural world vibrated with a pagan pantheistic sexual energy. I came to associate the Divine or Spirit World with the body. And the body and the natural world merged as one sacred sexual quintessence and primal source of poetry. Think of a Charles Burchfield painting (I was later to write a sequence a poems inspired by his paintings and diaries). I saw, felt, and heard the vibrating world as cosmic energy and holy ground. I ate the world. Although I found much nourishment in Christianity, and still do, I found myself at odds with the church, itself, during the period of Civil Rights integration when I was entering junior high. I left the church. I was reading the great mystic and Romantic writers such as Blake, Clare, Dickinson, Emerson, Keats, Lawrence, Rossetti, Rilke, Sitwell, Thomas, Thoreau, Whitman, and Yeats, but also discovering avant-garde and Modernist work such as that of Rimbaud, Jean Genet, Anais Nin, Eliot, Stein, and the Beats. My interest in visual art grew and I spent hours reading histories and studying the art of Surrealism, the Symbolists and Decadents, Art Nouveau, and the Aesthetic Movement. My first “adult” works written then and in my first year in college, were Surrealist, Symbolist, and heady with sophisticated nature imagery. Fortunately, in undergraduate school, I found myself in a unique experiment in education [Bachelor of Creative Arts] at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte inspired by the long-closed Black Mountain College. There were no classes, only seminars and inspired gatherings and activities, and in many senses students worked as apprentices with the faculty. Students were expected as much as possible to participate in, to attempt work in – preferably collaboratively – all of the disciplines the program offered: visual arts, dance, music, theater, and writing. The first year I was the only writing student. I thrived. I did it all. I fused as many disciplines as I could. Each semester students crafted a singular project of which the end result required proof of some level of success. My first project “product’ was a sequence of poems inspired by the paintings and writings of Vincent Van Gogh. The second focused on the Goddess religions. In the BCA I found confirmation, permission, the language for what I had always unconsciously been effecting … as you say in your question, intersecting in my creative life ecology, nature, spirituality, gay male sexuality, and the arts. This was also when hippie culture was permeating my generation’s culture. I began in junior high exploring the Desert Fathers and then other religions which meshed well with my childhood readings in folklore and myth. First Vedanta and Zen, and as I entered undergraduate school Sufism and the Tao. Later Celtic Christianity, Anthroposophy, Gnosticism, Buddhism, the philosophy of the Enneagram, and the work of Deepak Chopra informed my world-view and my artistic attentions. At UNCC I found myself amongst a group of aspiring writers many of whom were lesbian. My first advisor was well-known lesbian novelist Bertha Harris. Two art department professors Rita Schumaker (fabric artist) and Catherine Nicholson (theater) encouraged my multidisciplinary leanings, and my interest in the Feminist Movement and the nascent scholarship into the Mother Goddess religions and patriarchy. Rita, a Jungian, also taught me about synesthesia in the arts, while Catherine urged me even further to break the bounds of my small town experience. I was to meet Adrienne Rich and Robert Bly, and was chosen for a special seminar series with writer and spiritual philosopher Elizabeth Sewell [The Orphic Voice] whose presence and work solidified my affinity for combining poetry with spiritual pursuits. Ultimately I needed, and found, an important balance in Eastern poetry, and the work of writers [a partial list] William Carlos Williams, H.D., Merwin, Plath, Rich, Akhmatova, Annie Dillard, Millay, Stevie Smith, Doris Lessing, the Deep Image of Robert Bly and his school [James Wright, Spanish Surrealism for example], James Broughton, Lorine Niedecker, Jonathan Williams, and even the music of Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen. That’s when it all finally came together in a way that had been for most of my decades of writing, after the explosive youthful work, a spare nature-based spiritual revelatory mode. I finally had a language and path for celebrating and telling the Unity I had first felt in my boyhood visions. TER: How do you approach ekphrastic writing? Do you contemplate a random image until words come together, or do you wait until a work of art speaks to you and find your way in from there? Do you research the background of a painting or photograph, or the biography of the artist, or do you let the image alone spark your words? Jeffery Beam: [Laughter]. All of the above. It has been different every time, although I would never say any image has been random. I come across an image that perhaps I just simply love, or an image uncovered in research about an artist or place I am drawn to, or perhaps the Universe sends me an image [as when a friend sent me the image of Andrea del Sarto’s John the Baptist, although this friend didn’t know that for years I had been fascinated by the Baptist’s story and the many works of art of him]. I think generally the discovery of an inspiring image has come out of my readings and studies of art and art movements or visits to museums, and less frequently biographies. Once the image has me the response can be very different. On some occasions the poem births immediately. Other times I have returned to the knowledge base about the work or the artist or the subject and then let the poem come. Always, though, a moment arrives when you have to let the image speak. I have been fortunate in that throughout my writing life I have seldom had much revision to do after the first draft; what revision needed is accomplished aloud. The new book, Spectral Pegasus / Dark Movements, as mentioned above, came out of a sympathy and love for the work of Hicks-Jenkins. He was working in subjects that beguiled me, and in that case, Clive chose the subject, and I became its captive. It was the first and only time I have written ekphrastic work that was chosen for me. The essay in the book, "I Dreamed a Dream," by Sarah Parvin explains how I entered the project thinking I was going to be writing in my customary distinctive style “often elegant, sometimes aphoristic, Objectivist, concisely crisp, Gnostic and Zen-like.” I quickly realized the poems weren’t flourishing. I gave myself over, as a result, to a sort of automatic writing, much like my youthful surrealist work. Meditating in front of an image for hours and waiting for it to speak. It always did and each poem, every time, gobsmacked me … I can’t think of a better term. The encounters were great fun, and each time felt like becoming a child again. Those unexpected visions. TER: You have written poetry on a wide variety of artwork, from erotic antique photographs to Japanese woodcuts to sculptures to Durer paintings. What is your relationship to visual art beyond ekphrastic writing? How did it become so central to your poetry practice? Jeffery Beam: I made note above that even before the age of 14 I was making visual art. I spent a lot of time alone as a child, “making” things, even sneaking behind my mother on Sundays because using a pair of scissors was “work” and one wasn’t supposed to work on the Sabbath. I became a great reader, led by my grandmother, even before I entered school, and we used to spend hours looking at Life and Look magazines. In elementary school I began collecting classic children’s literature in editions that had lovely illustrations. I also had a View-Master, the stereoscopic toy popular in the 50s and 60s, and would spend hours viewing art and images of foreign countries. I remember entering a city-wide art contest in the second grade and winning an honourary mention. My plan then was to become a painter. These must have been the first inspirations and sources of my interest in visual art. I don’t remember particularly being directed toward visual art by any teachers, although I had a third grade teacher who enthusiastically directed my passion for reading. There was a Language Arts teacher in junior high who really pushed me as a poet, but also encouraged students to think and respond with visual art in her class. Certainly the time in the Bachelor of Creative Arts program, with its insistence on merging disciplines, must have been a generative moment. But I look back to my intense interest in visual arts in junior high and high school and the reading of and collecting of books of art history and truly can’t remember the original impulse other than these childhood providences of Look, Life, illustrated books, and a View-Master! The Surrealist, Symbolist and Decadent, and British Arts and Crafts movements, all cross-pollinated visual and literary arts. I found that invigorating and stimulating. Although I wasn’t writing ekphrastic poems at that time, to read them now you would sense how visual they are. Word paintings. Anaïs Nin, whose work I was also studying intensely in the BCA, and who wrote like a painter, demanded that one “Proceed from the dream outward ... alchemize the life of the mind into the life of the senses.” I took that as a prime imperative. I suppose the first ekphrastic poems were the Van Gogh ones, but soon after that came the five poems written in response to Dürer etchings, which became the central section of my first book The Golden Legend (Floating Island Publication, 1981). Both the Van Gogh and Dürer poems were written in response to my advisor, Rita, advocating integrating more synesthesia in my work. I had already become enthralled by Auden’s poem about Icarus, Musée des Beaux Arts, and William Carlos Williams’ sequence Pictures from Brueghel and I think it was those poems that motivated me to generate these first ekphrastic projects. After writing the poem, "St. Jerome in his Study" for the Dürer poems, I never looked back. Writing ekphrastic poems is just something I do with joy. I love the challenge of re-creating and elaborating the image and its story while remaining true to it. So often when I was growing up I was told to “write what you know.” But I have always been intensely interested in what I don’t know, and seek out readings and experiences that nourish that longing. Ekphrastic writing allows me to step outside of the known and enter unknown territory. TER: Your creations are elaborate and complex collaborations. It’s not just you and Hicks-Jenkins’ artworks, really, but an intense tapestry of connectivity with countless imagineers of poetry, mythology, music, art, and more. Can you simplify some of these relationships for us to help us understand how you are inspired and how you create? Jeffery Beam: Of course, I have six decades of curiosity and its accumulated lore about spiritual texts and spirituality, religion, art and art history, mythology, folklore, anthropology, psychology, philosophy, and even botany, horticulture, and physics from which to draw. I am by no means a genius or savant; my knowledge base is idiosyncratic and very personal. Ekphrastic meditations and creation rises out of my foundational “scholarship” and a keen willingness to learn and know; the process being as important as any product that might result. Process was an integral part of the BCA. Our primary, really only, textbook was potter/philosopher/teacher M.C. Richards’ book Centering in Pottery, Poetry and the Person. She wrote: “The material is not the sign of the creative feeling for life: of the warmth and sympathy and reverence which foster being; techniques are not the sign; 'art' is not the sign. The sign is the light that dwells within the act, whatever its nature or its medium.” With Spectral Pegasus / Dark Movements the nature of Clive’s blog led to a convocation of voices and talents in its creation. As for the rest of my ekphrastic work, and my work in general, it is my nature to absorb “globally.” Perhaps it is the result of the sympathetic shamanistic seer-like nature I was born into? Genetics? Those Celts! Perhaps it is a kind of schizophrenia, which I do think, as many artists are, I am on some spectrum of. What’s the term? Emotional intelligence. I am not a detailed person when it comes to creation. My memory is of impression, not necessarily fact. Within the Enneagram, I am a perfect Four, variously called The Tragic Romantic, The Individualist, a “feeling type.” The evolution outlined in my previous answers details a soul eager to merge, not just with the natural and spiritual worlds, but with the individual manifestations of the Great Mind (aka human beings) and their own singular ways of creative expressions. I find inspiration, new language, new imagery, in those shared connections. Most of my books employ the weaving of epigraphs either attached to individual poems or as opening section “anthologies” that add layers or soundings to the experience of the book. It feels, to me, as if I am mingling and conversing with those voices from the past. I like that. I am always on the lookout for possible collaborators in any art form. In Pegasus I found a subject that allowed me to create and communicate my own story in words through the integration of a lifetime’s worth of study, knowledge, skills, beliefs, and passions, while working with another artist working visually. That is the pleasure of any collaboration, but also the rapture I find in fashioning, as in your great word, a tapestry. And we mustn’t forget the term “fun.” How terrifyingly fun collaboration and synthesizing can be. TER: The ekphrastic technique of simply looking at an image and writing what comes to mind, without any background exploration, is seen by some as a kind of automatic writing. The arts have a long history of personifying inspiration as a muse or viewing inspiration as a mysterious process. Many musicians and painters and poets describe creativity as a connection to something beyond, something divine, some even describing a sense of channeling. In light of your spiritual beliefs about creativity, can you share your thoughts on the mystery of art and inspiration? Jeffery Beam: Early on, reading Blake and Rimbaud and Whitman convinced me of the relationship of poetry and the Divine. In Henry Miller’s astounding book on Rimbaud, The Time of the Assassins, he insists: To ask the poet to speak the language of the man in the street is like expecting the prophet to make clear his predictions. That which speaks to us from higher, more distant, realms comes clothed in secrecy and mystery. What belongs to the realm of spirit, or the eternal, evades all explanation. The language of the poet is asymptotic; it runs parallel to the inner voice when the latter approaches the infinitude of spirit. It is through this inner register that the man without language, so to speak, is in communication with the poet. Primitive peoples on the whole are poets of action, poets of life. They are still making poetry, though it moves us not. Were we alive to the poetic, we would not be immune to their way of life: we would have incorporated their poetry in ours, we would have infused our lives with the beauty which permeates theirs. I have oftentimes described my “place” in “my” work as one of being a conduit, a channel, from the Beyond. Being a poet, is a sacred trust. I have also often stated that I think of my work as writing spiritual texts in poetic form. In 2015 as part of the Faith in Arts series at St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church in Hillsborough, North Carolina I presented a career retrospective reading Beyond the Green Door which included excerpts from an essay by that name with the sub-title Spiritual Ecology in the Light of a Personal Poetics. I explained that unlike the Muse most poets claim, or the Angel that Rilke identified as his inspiration, I have always identified with Federico Garcia Lorca’s the duende as my Great I AM, my quantum energy, my Big Bang. Lorca states: All that has dark sounds has duende … These “dark sounds” are the mystery, the roots thrusting into the fertile loam known to all of us, ignored by all of us, but from which we get what is real in art … The duende is a power and not a behavior, it is a struggle and not a concept … duende surges up from the soles of the feet. Which means it is not a matter of ability, but of real live form; of blood; of ancient culture; of creative action … (it) is in fact the spirit of the earth ... The appearance of the duende always presupposes a radical change of all forms based on old structures. It gives a sensation of freshness wholly unknown, having the quality of a newly created rose, of miracle, and produces in the end an almost religious enthusiasm…The duende does not appear if it sees no possibility of death … In idea, in sound, or in gesture, the duende likes a straight fight with the creator on the edge of the well … While angel and muse are content with violin or measured rhythm, the duende wounds, and in the healing of this wound which never closes is the prodigious, the original in the work of man. The magical quality of a poem consists in its being always possessed by the duende, so that whoever beholds it is baptized with dark water … I have, since my high school days, been keeping a commonplace book of quotes about poetry, writing, and the spirit. It’s over 150 pages now and encompassing over 2000 quotations. I quote myself six times in it; here are two: Poetry is a religious act which requires the full range of human effort. I once described poetry as "the doorknob and the room." It requires honesty, sincerity, seriousness, and play. It requires we give up pretense and mental squalor. It requires love when love is necessary and destruction when destruction calls. It means touching the doorknob before you can enter the room. Go stand in a hurricane, then you'll know what the wind knows. What’s next for Jeffery Beam? Jeffery Beam: I have about 100 more quotes, currently, to type into the commonplace book, then although I won’t stop adding to it, I’d like to see it published soon. I have two children’s books seeking publishers, and hope they will be published as illustrated children’s books. One, a sort of Rip Van Winkle tale, recounts my old dog and me being captured by a group of fairies The Droods and waking up after 1000 years. Afterwards, Mr. Dog has learned to talk, and we both can fly. The other is a small collection of winter lullabies I’d like to see released with a recording of them being read and sung, and with song-sheets so parents could play the poem/songs on guitar or piano. I am working on a rather large anthology of bee poems throughout time, Bee, I’m Expecting You, which would also include some folklore and fact about bees. There is an opera libretto, way on a back burner, based on the Demeter / Persephone story. Young composers Steven Serpa, Holt McCarley, and Tony Solitro — all of whom have composed work based on my poems — plan to create other works. There will soon be a recording available of an operetta song cycle by Daniel Thomas Davis, Kith and Kin: Family Secrets, commissioned by singer Andrea Edith Moore, with texts from a number of well-known North Carolina writers. One of the songs is mine. Andrea is planning a concert in 2020 or 2021 of much of the music created from my poems, including some of my own lullabies and poem/songs. TER: Are there more ekphrastic works ahead? Jeffery Beam: It wouldn’t surprise me if there were. I’ll wait for their call. Spectral Pegasus/Dark Movements Jeffery Beam and Clive Hicks Jenkins Kin Press, 2019 Click on title three lines above to view or purchase at Amazon. Click on Kin Press directly above to view or purchase directly from publisher.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|