|

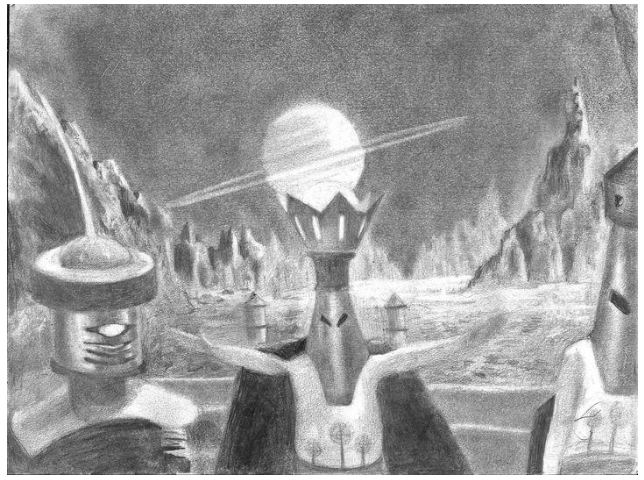

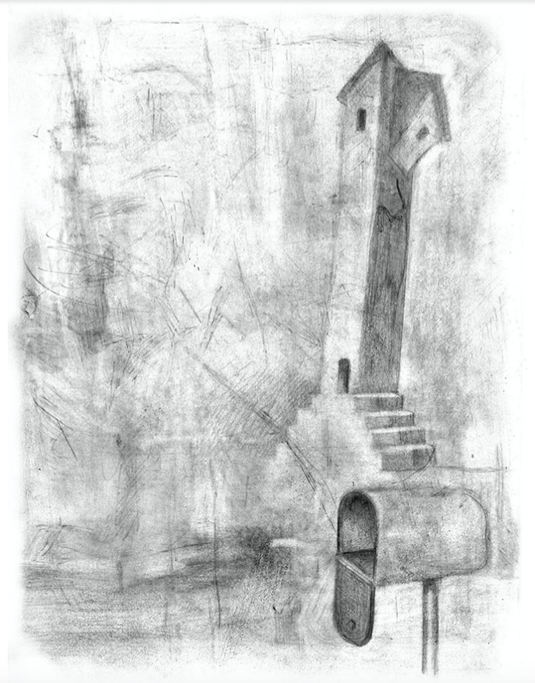

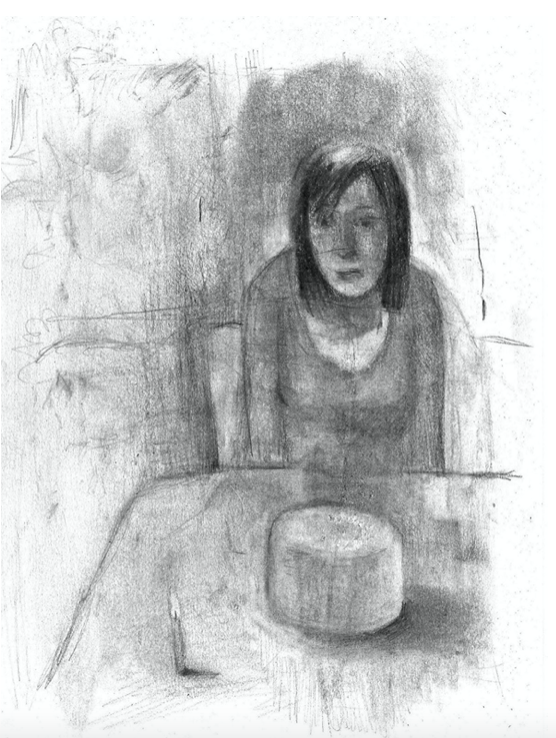

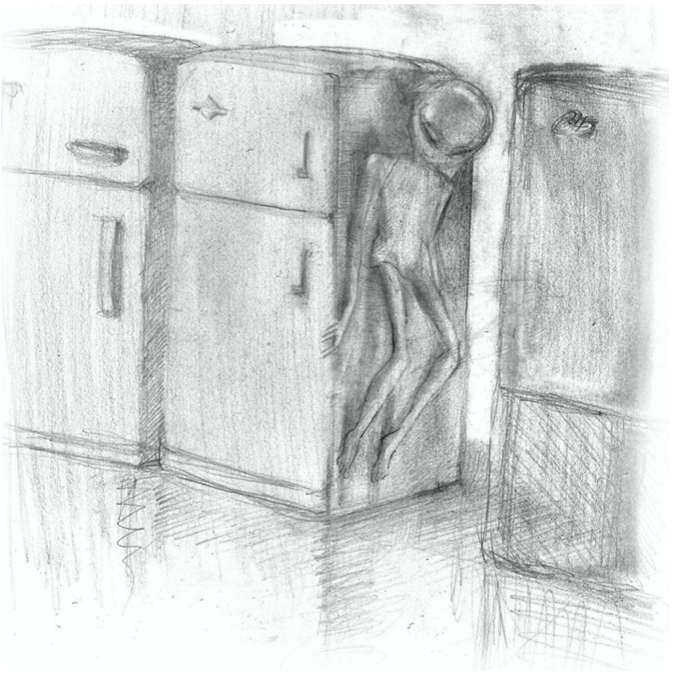

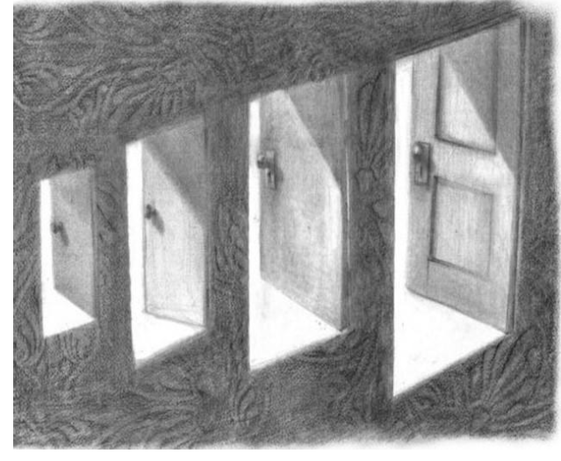

Stories from the Picture Box I set up a picture box on a downtown sidewalk, near a bench, and a tree. I put a drawing in, opened the doors, and began: "Gaito Kamishibai ( GAI-toe Kam-MISH-e-bye—"Outdoor Picture-Story Show") is Japanese story telling using pictures displayed in a portable box, often perched on the back of a bike. Storytellers with boxes were a common sight on the streets of Japan from the 1920s to the late 1950s. During WWII, kamishibai was enlisted for government propaganda, and reached its peak after the war, in the seven years of the U.S. occupation, (1945-1952). Before radios, movies or televisions were widely available, it conveyed public announcements and propaganda from the U.S. authorities in visual form, but at heart remained cheap street theatre, and income for demobbed soldiers turned storytellers. Everyone was hard scrabbling to make a few yen in the rubble and chaos of post-war reconstruction, and their stories and pictures were the grubby desperate birth yowls of manga to come. (And, I wonder, what else? And who were the storytellers, really? They did it to survive. They sure didn't get an MFA to learn how. Did they mix the news and kids' stuff with their personal views, inner demons? Did they parse those things out at all, or narrate a gumbo of gonzo journalism and PTSD nightmares? Nobody was in control. In those ruins, and ours, the stories could, and can be anything). Wait, our ruins? This is not 1946 Japan, it’s 21st Century United States. There is no meaningful comparison, or equivalence. But we have inherited the shadows that were burned into Hiroshima brick; we carry the plutonium in our bones. If and how we own the trauma of our histories seems the only stories in the box worth telling, even if I don't know how to draw or write or tell those tales at all. What will we make or do with those bricks of irradiated shadow? Build shelters? Erect walls? Pitch them into tear gas? Drop them down a well of dreams to listen, breathless, for the plunk? I closed the doors. Atomic Rulers of the World I put a drawing in the story box and opened the doors. The audience was one kid on the bench, kicking his legs and sucking on a thick straw from a jumbo cup. He said, "What's this?" The straw rattled air. "It's called Atomic Rulers of the World.” He nodded. “This drawing is of a scene from a cheap Japanese TV series from the late 1950s, featuring a character called Giant Man, or Star Man. Episodes were lumped together and dubbed in English as movies for U.S. TV in the early '60s. The Saturn in the sky gently sways on piano wire. I first saw this on TV, home from school with a bad fever, a rubber ice pack on my forehead that hurt with cold and seemed to drive the fever into the film. Here the High Council is meeting to stop another planet from irradiating all the planets in the system, including Earth. They summon Star Man. He has a white suit and a cape. He flies to Earth to capture the radioactive device and stop the invaders. When he flies, the wires holding him make little peaks in his back. The actor who played him, Ken Utsui, went on to a distinguished film career. He hated playing Star Man. He had to stuff his crotch with cotton to make it look bigger. After a Japanese boy wearing a Star Man costume died jumping from a window, Utsui quit the role, and never spoke about it again.” “Cool. Thanks.” The boy hopped off the bench and dumped his empty cup in a steel mesh trash can. Ice cubes clattered against the metal and I took it for applause. He walked away and I closed the doors. Return to Sender I put a drawing in the story box and opened the doors. The audience was a young woman on the bench in a FedEx uniform with two girls, maybe six, and twelve. The woman slouched and thumbed her phone. The younger girl's dark eyes had a jaguar prowl. The older girl stared, attentive or dazed at the drawing through glasses like ice. She poked the woman and said, "Look Mom, Rapunzel." The woman's eyes didn't leave her phone. "What?" The girl asked me, "Is this Rapunzel, like, let down your golden hair?" "I don't know. It's called, 'Return to Sender.'" The mother stayed glued to her phone but grinned and nodded ruefully. "I know that one." She sang imitation Elvis: "Return to sender/Add-dress unknown! / No such number/ No such zone!" The girl said, "That happens to you in your truck, right mom?" "That happens to me in my life." She laughed. She squinted at the drawing and said, "You can see the mailbox is open. Rapunzel answered his call and let down her golden hair before he could check the mail, so he left it open and climbed her hair. But it was a wig and came loose when he was half way up the tower. He plunged to his death, never to see Rapunzel's face, or the letter returned to him from the unknown zone. The End." The girl shook her head. "That's not what happened." “No? OK, he saw the stamped letter and thought, what the hell, I’ll call blondie. Then he broke his neck.” The silent younger girl's voice was growly and startling. "That's the wizard's tower. He's sad. He can't spell anymore. And nobody sent him a letter today." I closed the doors. Azure Profundo I put a drawing in the story box and opened the doors. There was a chunky young guy and his friend, small and gaunt. The chunky guy hunched meekly on the bench but his skinny friend sat in a confident sprawl. Both wore drooping t-shirts displaying heavy metal bands in Spanish. I began: "In the mid-twentieth century, most neighbourhoods had a street ending in an electrical substation. On those streets there was always one family with twin girls, and sometimes, identical triplets. The buzzing from the insulating coils made the girls' braces into radios. Implanted I-Pods were born.” The bigger man raised his hand, as if in school. “This is a story, right? About a North American twentieth century?” “Yes.” “Because I was going to say, in Mexico every neighbourhood would have a maquiladora. A factory. Every street would have an asthmatic girl with a cleft lip. And I think the coil thing looks like a kind of chess piece. A pawn. When I was a kid me and my friends, we played a lot of chess. Chess and video games. I was a pawn man. My friends said when that computer, Azure Profundo, that Deep Blue, beat Kasparov in the ’97 rematch, it was the end of the Grand Masters, but I don’t believe that." His friend nodded vigorously and jabbed the other's shoulder. "You know what I think? I think that thing looks like a pile of poop. Poop with a light on top." "Dude ate a light bulb and shit it out." They both cackled, and the big kid added, "Remember what Trump said, that you could cure Covid by inserting a bright light into your body? Maybe he just swallowed the light and shit it out. That's Melania and Ivanka and what's her name, Ivana?—come see his last poop." All of us laughed. I closed the doors. Woman at Kitchen Table I put a drawing in the story box and opened the doors. I said, "This is called 'Woman at Kitchen Table.'" Two women had come by to rest on the bench. They wore mismatched shawls, scarves, long bright skirts and knit caps with the local university football logo, a swaggering badger. The younger, in her 50's, shelled a boiled egg on her lap. The older was short and stooped and bobbed her sandaled feet over the ground, grinning and chattering to her companion in Hindi, or was it Nepali? I could see my story would be talked over by Hindi, or Nepali. One of their cell phones rang with a Wah-Wah, "Failure" jingle. They let it ring. I began: "This is a woman having a birthday party of one." The older woman laughed. "One year old." I said, "I mean, she is alone." "No," the younger woman said, "No year. No candle in the cake." The other said, "Candle on the table." "She's a baby." "She's before baby. She's waiting for her number one birthday." I asked, "She's waiting to be born?" They laughed. I asked, "Where do you wait to be born?" The older woman shrugged impatiently. "At the kitchen table." I closed the doors. Smart Refrigerator I put a drawing in the story box and opened the doors. There was no one listening. “A husband and wife’s refrigerator got hot. At the appliance store the wife went to a row of ‘smart refrigerators.’ As the salesman talked, she took her husband’s hand and surreptitiously slipped him a small object, as if passing a file for a jail break. It was a little rubber alien, made of metallic blue gooey rubber. The salesman was saying, ‘These smart refrigerators can read recipes to you, leave messages on the touch screen door, show you on your phone their insides, without having to open the door. You can watch the inside, in real time.’ The husband said, ‘Why in the world would I want to do that?’ He gripped the tiny alien. The wife said, ‘If there is a child who has gone inside to play or hide, and becomes trapped, this feature could save their life.’ The salesman was alarmed. ‘That could never, ever happen today! No refrigerators on the market latch from the outside.’ He went on. ‘But say for example you are in the store and can’t remember if you are out of milk. You could ‘call’ your refrigerator and see what’s inside. Here. Let me demonstrate.’ He took out his phone and dialed a number. A video screen appeared with a gulp sound. He handed the phone to the couple. The husband looked at the white interior. ‘What’s that?’ On the top shelf was a little figure. The salesman said, ‘Huh.’ He opened the refrigerator, and inside was the blue rubber alien. ‘Some kid must have been playing around.’ The wife nodded with satisfaction. The husband opened his hand. It was empty and released a puff of chilled air.” “And they can watch you.” A tall woman in hoodie and sunglasses was leaning against the tree, smoking in the sun. “Smart is always watching.” I nodded and closed the doors. Matrimony I put a drawing in the story box and opened the doors. On the bench was a woman with a fisherman’s vest and tiny pug dog on a leash, curled and panting at her feet. I began: “A man married and had everything yet wanted only to be alone. Over the years the one thing he kept for himself was always waiting in the basement. His wife knew better than to ask, and had certainly never been allowed to see it, or interrupt him when he was working. Still, to be certain, he had installed multiple locks and doors in the back of the basement. These would have to be passed through to get to the work room. The first door was a cheap hollow wood door with a simple combination lock. Behind that was a sliding metal fire door with a pass code and a thumb print reader. Next was a steel blast door with a retinal scan, and a voice identification box. Next was a tiny door, like in Alice in Wonderland, just large enough to crawl through. Then a swaying curtain of clattering ceramic beads that analyzed skin particles off your hand or arm or shoulder, and that sprouted poison barbs if they registered any DNA but his own. The final door was like the first one, a hollow fiberboard slab with a metal hasp and a combination lock. This door opened into a blank white room, the work room. It was softly lit with a stretch of low, indirect lighting behind one wall’s baseboard. A single stuffed armchair sat in the middle, made of an inviting brushed material the color of seashells, on dark wood rockers instead of legs. He rocked. On the floor facing the chair was a black and white photograph of his wife. She was looking directly back at the camera, wearing no expression and no makeup, her hair pulled back and fastened into a bun. It was a new photo. He was always careful to keep it up to date. The rocking chair made a pleasing soft bump on the wood floor but otherwise it was still. He was safe from any disturbance, free to see his wife without worry or interruption.” The woman on the bench said, “This is why I live with a dog.” I nodded and closed the doors. Gregg Williard Gregg Williard is an artist and writer. His work has recently appeared in Conjunctions, Vine Leaf Press, Phoebe and Revolution John.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|